Measuring Transparency: Towards a Greater Understanding of Systemic Transparence and Accountability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combating Corruption Through Corporate Transparency Using Enforcement Discretion to Improve Disclosure David Hess

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Journal of International Law 2012 Combating Corruption through Corporate Transparency Using Enforcement Discretion to Improve Disclosure David Hess Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hess, David, "Combating Corruption through Corporate Transparency Using Enforcement Discretion to Improve Disclosure" (2012). Minnesota Journal of International Law. 318. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil/318 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Journal of International Law collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article Combating Corruption through Corporate Transparency: Using Enforcement Discretion to Improve Disclosure David Hess ABSTRACT This article builds on the increased attention given to corruption as an issue of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the increased enforcement of anti-bribery laws in the United States, to consider how enforcement activity can work to improve corporate transparency and support initiatives developed in the field of corporate social responsibility, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Although the GRI requires disclosure on anti-corruption matters, currently, few companies are providing disclosure on this issue and those that are disclosing rarely provide useful information to stakeholders. This article shows how recent trends in criminal and civil law enforcement can be modified slightly to provide strong incentives for companies to disclose information required by the GRI or other social reporting standards. The article then shows how the proposal can assist current enforcement practices directly, but also indirectly by supporting CSR initiatives designed to help combat the enabling environment that allows corruption to thrive. -

11. Conflicts of Interest

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Anti-Bribery Guidance Chapter 11 Transparency International (TI) is the world’s leading non-governmental anti-corruption organisation. With more than 100 chapters worldwide, TI has extensive global expertise and understanding of corruption. Transparency International UK (TI-UK) is the UK chapter of TI. We raise awareness about corruption; advocate legal and regulatory reform at national and international levels; design practical tools for institutions, individuals and companies wishing to combat corruption; and act as a leading centre of anti-corruption expertise in the UK. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank DLA Piper, FTI Consulting and the members of the Expert Advisory Committee for advising on the development of the guidance: Andrew Daniels, Anny Tubbs, Fiona Thompson, Harriet Campbell, Julian Glass, Joshua Domb, Sam Millar, Simon Airey, Warwick English and Will White. Special thanks to Jean-Pierre Mean and Moira Andrews. Editorial: Editor: Peter van Veen Editorial staff: Alice Shone, Rory Donaldson Content author: Peter Wilkinson Project manager: Rory Donaldson Publisher: Transparency International UK Design: 89up, Jonathan Le Marquand, Dominic Kavakeb Launched: October 2017 © 2018 Transparency International UK. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in parts is permitted providing that full credit is given to Transparency International UK and that any such reproduction, in whole or in parts, is not sold or incorporated in works that are sold. Written permission must be sought from Transparency International UK if any such reproduction would adapt or modify the original content. If any content is used then please credit Transparency International UK. Legal Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. -

Business Ethics: a Panacea for Reducing Corruption and Enhancing National Development

Nigerian Journal of Business Education (NIGJBED) Volume 5 No.2, 2018 BUSINESS ETHICS: A PANACEA FOR REDUCING CORRUPTION AND ENHANCING NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AKPANOBONG, UYAI EMMANUEL, Ph.D. Department of Vocational Education, Faculty of Education, University of Uyo Email:[email protected] Abstract In recent times there are scandals of unethical behaviours, corrupt practices, lack of accountability and transparency amongst public officials, political office holders, business managers and employees in the country. Therefore, there is an urgent need for public sector institutions to strengthen the ethics of their profession, integrity, honesty, transparency, confidentiality, and accountability in the public service. The paper further attempt to discuss the need for business ethics and some practices and behaviours which undermined the ethical behaviours of public official with strong emphasis on corruptions causes and preventions, conflicts of interest, consequences of unethical behaviour and resources management. The paper also outlined some measures on how to combat the evil called corruption in public service and business organizations. It is concluded that if all measures are taken into consideration the National Development may be achieved. Keywords: Ethics, unethical, transparency, accountability, corruption. Introduction In every business organization, there must be a laid down rules, values norms, order and other guiding principles which may be in form of ethics. The essence of this is to guide both the employer and the employees in achieving the organizational goals and at the same time help in checks and balances. Luanne (2017 saw ethics as the principles and values an individual uses to govern his activities and decisions. Therefore, Business Ethics could be described as that aspect of corporate governance that has to do with the moral values of managers encouraging them to be transparent in business dealing (Chienweike, 2010). -

Social Accountability International (SAI) and Social Accountability Accreditation Services (SAAS)

Social Accountability International (SAI) and Social Accountability Accreditation Services (SAAS) Profile completed by Erika Ito, Kaylena Katz, and Chris Wegemer Last edited June 25, 2014 History of organization In 1996, the Social Accountability International (SAI) Advisory Board was created to establish a set of workplace standards in order to “define and verify implementation of ethical workplaces.” This was published as the first manifestation of SA8000 in 1997.1 The SAI Advisory Board was created by the Council on Economic Priorities (CEP) in response to public concern about working conditions abroad. Until the summer of 2000, this new entity was known as the Council on Economic Priorities Accreditation Agency, or CEPAA.2 Founded in 1969, the Council on Economic Priorities, a largely corporatefunded nonprofit research organization, was “a public service research organization dedicated to accurate and impartial analysis of the social and environmental records of corporations” and aimed to “to enhance the incentives for superior corporate social and environmental performance.”3 The organization was known for its corporate rating system4 and its investigations of the US defense industry.5 Originally, SAI had both oversight of the SA8000 standard and accreditation of auditors. In 2007, the accreditation function of SAI was separated from the organization, forming Social Accountability Accreditation Services (SAAS).6 The operations and governance of SAI and SAAS remain inexorably intertwined; SAI cannot function without the accreditation services of SAAS, and SAAS would not exist without SAI’s maintenance of the SA8000 standards and training guidelines. They see each other as a “related body,” which SAAS defines as “a separate legal entity that is linked by common ownership or contractual arrangements to the accreditation body.”7 Because of this interdependence, they are often treated by activists and journalists as a single entity. -

2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor Or Forced Labor

From Unknown to Known: Asking the Right Questions to The Story Behind Our Stuff Trace Abuses in Global Supply Chains DOWNLOAD ILAB’S COMPLY CHAIN AND APPS TODAY! Explore the key elements Discover of social best practice COMPLY CHAIN compliance 8 guidance Reduce child labor and forced systems 3 labor in global supply chains! 7 4 NEW! Explore more than 50 real 6 Assess risks Learn from world examples of best practices! 5 and impacts innovative in supply chains NEW! Discover topics like company responsible recruitment and examples worker voice! NEW! Learn to improve engagement with stakeholders on issues of social compliance! ¡Disponible en español! Disponible en français! Check Browse goods countries' produced with efforts to child labor or eliminate forced labor 1,000+ pages of research in child labor the palm of your hand! NEW! Examine child labor data on 131 countries! Review Find child NEW! Check out the Mexico laws and labor data country profile for the first time! ratifications NEW! Uncover details on 25 additions and 1 removal for the List of Goods! How to Access Our Reports We’ve got you covered! Access our reports in the way that works best for you. On Your Computer All three of the U.S. Department of Labor’s (USDOL) flagship reports on international child labor and forced labor are available on the USDOL website in HTML and PDF formats at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor. These reports include Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, as required by the Trade and Development Act of 2000; List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, as required by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005; and List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor, as required by Executive Order 13126. -

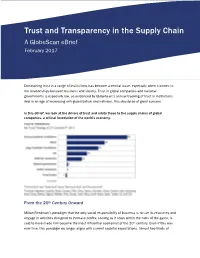

Trust and Transparency in the Supply Chain a Globescan Ebrief

Trust and Transparency in the Supply Chain A GlobeScan eBrief February 2017 Supply Chain – A Matter of Trust Diminishing trust in a range of institutions has become a central issue, especially when it comes to the relationships between business and society. Trust in global companies and national governments is especially low, as evidenced by GlobeScan’s annual tracking of trust in institutions. And in an age of increasing anti-globalization and nativism, this should be of great concern. In this eBrief, we look at the drivers of trust and relate these to the supply chains of global companies, a critical foundation of the world’s economy. From the 20th Century Onward Milton Friedman’s paradigm that the only social responsibility of business is to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase profits, so long as it stays within the rules of the game, is said to have made him become the most influential economist of the 20th century. Even if this was ever true, this paradigm no longer aligns with current societal expectations. Almost two-thirds of Trust and Transparency in the Supply Chain: A GlobeScan eBrief consumers around the world expect companies to do more than just make money – and they expect governments to play a role in this as well. These expectations have been trending upward for the past 15 years, and reached an all-time high in 2016. When asked more specifically, the global public has an extensive list of expectations of companies, with ensuring safe products on top, followed by providing fair wages, not harming the environment and ensuring responsible supply chains. -

Chapter 4 Accountability and Transparency

4. ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY – 79 Chapter 4 Accountability and transparency Businesses and citizens expect the delivery of regulatory outcomes from government and regulatory agencies, and the proper use of public authority and resources to achieve them. Regulators are generally accountable to three groups of stakeholders: i) ministers and the legislature; ii) regulated entities; and iii) the public. This chapter provides guidance on the accountability structures and transparency mechanisms that should be in place for effective regulators. THE GOVERNANCE OF REGULATORS © OECD 2014 80 – 4. ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY Principles for accountability and transparency Accountability and transparency to the minister and the legislature 1. The expectations for each regulator should be clearly outlined by the appropriate oversight body. These expectations should be published within the relevant agency’s corporate plan. 2. Regulators should report to ministers or legislative oversight committees on all major measures and decisions on a regular basis and as requested. 3. Governments and/or the legislator should monitor and review periodically that the system of regulation is working as intended under the legislation. In order to facilitate such reviews the regulator should develop a comprehensive and meaningful set of performance indicators. Accountability and transparency to regulated entities 4. Information and access to appeal processes and systems should be made easily available to regulated entities by regulators. Regulators should establish and publish processes for arm’s length internal review of significant delegated decisions (such as those made by inspectors). 5. Regulated entities should have the right of appeal of decisions that have a significant impact on them, preferably through a judicial process. -

Review of Impact and Effectiveness

SynthesisSynthesis reportreport ReviewImpact of and impact effectiveness and effectiveness of transparency ofand transparency accountability and initiativesaccountability initiatives RosemaryRosemary McGee McGee & &John John Gaventa Gaventa withwith contributions contributions from: from: GregGreg Barrett, Barrett, Richard Richard Calland, Calland, Ruth Ruth Carlitz, Carlitz, AnuradhaAnuradha Joshi Joshi and and Andrés Andrés Mejía Mejía Acosta Acosta For more information contact: Transparency & Accountability Initiative c/o Open Society Foundation 4th floor, Cambridge House 100 Cambridge Grove London, W6 0LE, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7031 0200 www.transparency-initiative.org Copyright © 2010 Institute of Development Studies. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this report or portions thereof in any form. TAI Impacts and Effectiveness /Synthesis report 3 Contents Executive summary 5 1. Background of the project 9 2. Definitions and conceptual issues 12 3. Aims, claims, assumption and critiques 15 4. What evidence is available? 19 Service delivery initiatives 20 Budget process initiatives 22 Freedom of information 24 Natural resource governance initiatives 26 Aid Transparency 28 Summary of evidence 30 5. How do we know what we know? 33 Methodological approaches 34 Methodological choices, challenges and issues 36 6. What factors make a difference? 42 State responsiveness (supply) factors 44 Citizen voice (demand) factors 45 At the intersection: factors linking state and society accountability mechanisms 45 Beyond the simple state-society -

A Guide to Best Practice in Transparency, Accountability and Civic Engagement Across the Public Sector

Open government data A guide to best practice in transparency, accountability and civic engagement across the public sector The Transparency and Accountability Initiative is a donor collaborative that includes the Ford Foundation, Hivos, the International Budget Partnership, the Omidyar Network, the Open Society Foundations, the Revenue Watch Institute, the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. The collaborative aims to expand the impact, scale and coordination of funding and activity in the transparency and accountability field, as well as explore applications of this work in new areas. The views expressed in the illustrative commitments are attributable to contributing experts and not to the Transparency and Accountability Initiative. The Transparency and Accountability Initiative members do not officially endorse the open government recommendations mentioned in this publication. For more information contact: Transparency & Accountability Initiative c/o Open Society Foundation 4th floor, Cambridge House 100 Cambridge Grove London, W6 0LE UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7031 0200 E: [email protected] www.transparency-initiative.org Copyright 2011. Creative Commons License. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/ 1 Open government data / Opening government Open government data Contributor: Centre for Internet and Society – India Openness in relation to information on governmental collected by the government), there are also areas where functioning is a crucial component of democratic the two categories do not overlap. Openness with respect governance. There are few things more abhorrent to government-produced information is part of the right of to democracies than a lack of transparency in their the public to access any output of taxpayer funding. -

Ethics and Transparency

Sustainability at AstraZeneca Access to healthcare Environmental protection Ethics and transparency Ethics and transparency Our approach Compliance Supply chain management Patient safety and product security Bioethics Antimicrobial resistance We want to be valued for the medicines we provide Ethics and and trusted for the way we work. That means leading our industry in demonstrating ethical business practices and high levels of integrity in everything transparency we do. It is why human rights, safety and health, environmental protection and business ethics are core to AstraZeneca’s approach to sustainability. Compliance Managing our Product security We emphasise to all our staff the supply chain The illegal trade in medicines is importance of compliance with our a public health risk and our aim is to AstraZeneca Values, Code of Conduct We extend our high ethical standards disrupt this activity by working with and supporting requirements. We to our whole supply chain and regularly partners around the globe. empower our people to ask questions check and audit that our suppliers when they are unclear or make a report reflect our Values. when they have a concern. 100% 8,977 $16.5 million of active employees trained on supplier assessments carried worth of AstraZeneca counterfeit the Code of Conduct out in 2016 and illegal medicines seized Animals Antimicrobial in science resistance We apply a single, consistent Global Although we no longer develop small Standard for animal welfare and are molecule antimicrobials in-house, we’re committed -

GLOBAL SUSTAINABILITY SOLUTIONS Sustainability Solutions

GLOBAL SUSTAINABILITY SOLUTIONS Sustainability Solutions Companies are increasingly facing challenges in their sourcing, production and distribution chains, as well as addressing consumers’ expectations for corporate sustainable responsibility of their products, services and behaviors. Intertek’s Total Quality Assurance proposition recognizes that with increasing value chain complexity, our clients need a trusted partner and integrative sustainable solutions that provide confidence and peace of mind. Our services range from solutions to address immediate environmental, social and ethical compliance to the development of strategic portfolio initiatives, such as stakeholder engagement programs, sustainable supply chain management tools, reporting and assurance. Our proven value chain expertise, global network and on-the-ground local knowledge help our customers with increased transparency to manage risk and resiliency, whilst supporting their ability to operate effectively and act responsibly. Our customers trust us to ensure quality, safety and sustainability in their business, to protect their brands and to help them gain competitive advantage. We not only provide valuable insight into companies’ current sustainability needs, we identity emerging trends, enabling our customers to manage the circular economy in their business and safeguard their reputation. Through our global network of Sustainability Experts and integrated Assurance, Testing, Inspection, and Certification solutions, Intertek is uniquely placed to help organisations understand, -

Up a Notch Founding Partner of Van They fi Le Bankruptcy, Categories of Corporate/ Horn Law Group, Has That They’Re the Only One M&A As Well As Banking by CARL A

GUEST COLUMN SFLG BRIEFING of Tina Locatelli from and deep insight and especially Brazil,” said and Vera Rechsteiner have associate to counsel in compassion “ AXS founding partner been recognized among Miami. Locatelli joined Recio’s practice Ben Wolkov. the top 100 attorneys the fi rm in 2017 and focuses primarily on the Moreland’s work from international law was one of fi ve lawyers representation of private includes providing legal fi rms working in Latin fi rmwide recognized for developers in land use counsel on high-yield America by Latinvex, an their accomplishments and zoning matters, along Euro bonds and sovereign online publisher of news and outstanding client with real estate investors bond issuances and and analysis of Latin service. and private lenders in structured fi nance America business. Her practice focuses South Florida. transactions, including Alonso was named a on structured and future-fl ow receivables leader in the categories Federal government might take Chad Van Horn corporate fi nance, and pre-export of corporate/mergers including agency transactions. He also and acquisitions and corporate transparency The Debt Life hits a options. mortgage-backed advises on mergers and banking and fi nance. No. 1 spot on Amazon “Sometimes people securities and mortgage acquisitions and private Margarit was selected Chad Van Horn, feel like a failure when warehouse facilities. equity transactions. as a top lawyer in the up a notch founding partner of Van they fi le bankruptcy, categories of corporate/ Horn Law Group, has that they’re the only one M&A as well as banking BY CARL A.