Guidance Document for Social Accountability 8000 (Sa8000®:2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Wage and Hour Risks in a Digitally Connected World

A Matter of Time: Managing Wage and Hour Risks in a Digitally Connected World Prepared by Jeffrey Brecher Jackson Lewis P.C. (631) 247-4652 | [email protected] Eric Magnus Jackson Lewis P.C. (404) 586-1820 | [email protected] This paper is meant to provide information of a general and educational nature and does not constitute legal advice or create an attorney-client relationship. Readers should consult counsel of their own choosing to discuss how these matters relate to their individual circumstances. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their firm or its principals or clients. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without the express written consent of Jackson Lewis. ©2017 Jackson Lewis P.C. This paper is scheduled to be published in the June 2017 edition of the Journal of Internet Law, produced by Aspen Publishing. The authors would like to thank Jackson Lewis Associate, Roberto Concepcion, for his assistance with the preparation of this paper. 1 I. Introduction Many people are addicted to their phones. They check them constantly throughout the day (sometimes every few minutes) to determine whether a new e-mail or text message has been sent or a new item posted on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and the myriad other social media applications that exist. To ensure immediate notification of incoming mail, users can also set their phone to provide an audio notification when a new e-mail, voicemail, or text message has arrived, and select from hundreds of tones to announce the message—whether a “chime,“ “ding,” or “swoosh.” But some of those addicts checking their phones are employees, and they are checking their phones for work related e-mail and messages. -

Recordkeeping Requirements Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (Revised July 2008) Fact Sheet #21: Recordkeeping Requirements under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides a summary of the FLSA's recordkeeping regulations, 29 CFR Part 516. Records To Be Kept By Employers Highlights: The FLSA sets minimum wage, overtime pay, recordkeeping, and youth employment standards for employment subject to its provisions. Unless exempt, covered employees must be paid at least the minimum wage and not less than one and one-half times their regular rates of pay for overtime hours worked. Posting: Employers must display an official poster outlining the provisions of the Act, available at no cost from local offices of the Wage and Hour Division and toll-free, by calling 1-866-4USWage (1-866-487-9243). This poster is also available electronically for downloading and printing at http://www.dol.gov/osbp/sbrefa/poster/main.htm. What Records Are Required: Every covered employer must keep certain records for each non-exempt worker. The Act requires no particular form for the records, but does require that the records include certain identifying information about the employee and data about the hours worked and the wages earned. The law requires this information to be accurate. The following is a listing of the basic records that an employer must maintain: 1. Employee's full name and social security number. 2. Address, including zip code. 3. Birth date, if younger than 19. 4. Sex and occupation. 5. Time and day of week when employee's workweek begins. 6. -

Fair Trade As an Example

Draft for Journal of Social Enterprise (In press) What Does it Mean To Do Fair Trade? Ontology, praxis, and the ‘Fair for Life’ certification system _____________________________________________________________________ Abstract The article discusses dynamics of interpretation concerned with what it means to do fair trade. Moving beyond the tendency to see heterogeneous practices as parallel interpretations of a separate concept – usually defined with reference to the statement by F.I.N.E – the paper seeks to provide an ontological account of the subject by drawing on theories of language, and John Searle’s notion of “institutional facts”. In seeking to establish the value of interpreting discourse and practice as mutually constitutive of the fair trade concept itself, the paper applies this alternative theoretical framework to both an historical account of fair trade movement and critical analysis of a new alternative certification programme: Fair for Life. Overall, analysis compliments political economy explanations for alternative fair trade approaches with a deeper theorisation of how such competition plays out in linguistic constructions and the wider understanding of the fair trade concept itself: a dynamic that, it is argued, will play a significant role in dictating the nature and therefore impact of fair trade governance, both now and in the future. 1 Draft for Journal of Social Enterprise (In press) Introduction One of the most prominent themes within the academic analysis of fair trade is the heterogeneous nature of practices associated with the term. This issue has been explored from the historical perspective (Gendron et al. 2009; Low and Davenport 2006) and much work addresses how the fair trade movement has been impacted by the development of third-party certification (Edward and Tallontire 2009; Renard 2005). -

Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges

LAURA T. RAYNOLDS Professor, Department of Sociology, Director, Center for Fair & Alternative Trade, Colorado State University Email: [email protected] Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges ABSTRACT Fairtrade International certification is the primary social certification in the agro-food sector in- tended to promote the well-being and empowerment of farmers and workers in the Global South. Although Fairtrade’s farmer program is well studied, far less is known about its labor certification. Helping fill this gap, this article provides a systematic account of Fairtrade’s labor certification system and standards and com- pares it to four other voluntary programs addressing labor conditions in global agro-export sectors. The study explains how Fairtrade International institutionalizes its equity and empowerment goals in its labor certifica- tion system and its recently revised labor standards. Drawing on critiques of compliance-based labor stand- ards programs and proposals regarding the central features of a ‘beyond compliance’ approach, the inquiry focuses on Fairtrade’s efforts to promote inclusive governance, participatory oversight, and enabling rights. I argue that Fairtrade is making important, but incomplete, advances in each domain, pursuing a ‘worker- enabling compliance’ model based on new audit report sharing, living wage, and unionization requirements and its established Premium Program. While Fairtrade pursues more robust ‘beyond compliance’ advances than competing programs, the study finds that, like other voluntary initiatives, Fairtrade faces critical challenges in implementing its standards and realizing its empowerment goals. KEYWORDS fair trade, Fairtrade International, multi-stakeholder initiatives, certification, voluntary standards, labor rights INTRODUCTION Voluntary certification systems seeking to improve social and environmental conditions in global production have recently proliferated. -

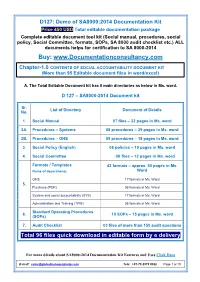

SA 8000:2014 Documents with Manual, Procedures, Audit Checklist

D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Chapter-1.0 CONTENTS OF SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY DOCUMENT KIT (More than 95 Editable document files in word/excel) A. The Total Editable Document kit has 8 main directories as below in Ms. word. D 127 – SA8000-2014 Document kit Sr. List of Directory Document of Details No. 1. Social Manual 07 files – 22 pages in Ms. word 2A. Procedures – Systems 08 procedures – 29 pages in Ms. word 2B. Procedures – OHS 09 procedures – 18 pages in Ms. word 3. Social Policy (English) 08 policies – 10 pages in Ms. word 4. Social Committee 08 files – 12 pages in Ms. word Formats / Templates 43 formats – approx. 50 pages in Ms. Name of departments Word OHS 17 formats in Ms. Word 5. Purchase (PUR) 05 formats in Ms. Word System and social accountability (SYS) 17 formats in Ms. Word Administration and Training (TRG) 05 formats in Ms. Word Standard Operating Procedures 6. 10 SOPs – 15 pages in Ms. word (SOPs) 7. Audit Checklist 03 files of more than 150 audit questions Total 96 files quick download in editable form by e delivery For more détails about SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Features and Uses Click Here E-mail: [email protected] Tele: +91-79-2979 5322 Page 1 of 10 D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Part: B. -

11. Conflicts of Interest

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Anti-Bribery Guidance Chapter 11 Transparency International (TI) is the world’s leading non-governmental anti-corruption organisation. With more than 100 chapters worldwide, TI has extensive global expertise and understanding of corruption. Transparency International UK (TI-UK) is the UK chapter of TI. We raise awareness about corruption; advocate legal and regulatory reform at national and international levels; design practical tools for institutions, individuals and companies wishing to combat corruption; and act as a leading centre of anti-corruption expertise in the UK. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank DLA Piper, FTI Consulting and the members of the Expert Advisory Committee for advising on the development of the guidance: Andrew Daniels, Anny Tubbs, Fiona Thompson, Harriet Campbell, Julian Glass, Joshua Domb, Sam Millar, Simon Airey, Warwick English and Will White. Special thanks to Jean-Pierre Mean and Moira Andrews. Editorial: Editor: Peter van Veen Editorial staff: Alice Shone, Rory Donaldson Content author: Peter Wilkinson Project manager: Rory Donaldson Publisher: Transparency International UK Design: 89up, Jonathan Le Marquand, Dominic Kavakeb Launched: October 2017 © 2018 Transparency International UK. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in parts is permitted providing that full credit is given to Transparency International UK and that any such reproduction, in whole or in parts, is not sold or incorporated in works that are sold. Written permission must be sought from Transparency International UK if any such reproduction would adapt or modify the original content. If any content is used then please credit Transparency International UK. Legal Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. -

Participatory Analysis of the Use and Impact of the Fairtrade Premium The

Participatory analysis of the use and impact of the fairtrade premium Response from the commissioning agencies, Fairtrade Germany and Fairtrade International, to an independent mixed-methods study of use and impact of Fairtrade Premium conducted by Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Sciences Innovations Sociétés (LISIS). The study at a Glance Introduction Researchers from the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Sciences Innovations Sociétés (LISIS) conducted a mixed-methods based study with the aim of analysing how the Fairtrade Premium has been used by Fairtrade organizations and how it generates benefits for Fairtrade farmers, workers and their communities. Five cases were explored: a coffee/cocoa small-scale producer organization (SPO) in Peru, a cocoa SPO in Côte d’Ivoire, a banana SPO in Ecuador, a banana SPO in Peru, and flower plantation in Kenya. Fairtrade Premium is one of the key interventions in the Fairtrade approach, as distinct from the Fairtrade Minimum Price. The Fairtrade Premium is an extra sum of money, paid on top of the selling price, that farmers or workers invest in projects of their choice. Over time, rules governing the use of Fairtrade Premium evolved to allow producer organizations to have greater autonomy over how Premium could be used. While Fairtrade case studies and examples of Fairtrade Premium projects exist, this study is the first to explore the pathways to impact that the Fairtrade Premium creates for Fairtrade producer organizations and their members. Approach The researchers followed Fairtrade’s Theory of Change in reviewing existing findings from other published studies, which suggested that the Fairtrade Premium is used to invest in farmers and workers, their organizations and communities (direct outputs of the Premium intervention). -

The International Fair Trade Charter

The International Fair Trade Charter How the Global Fair Trade Movement works to transform trade in order to achieve justice, equity and sustainability for people and planet. Launched on 25 September 2018 Copyright TransFair e.V. CONTENTS OVERVIEW CHAPTER THREE 03 OVERVIEW 17 FAIR TRADE’S UNIQUE APPROACH 04 ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL FAIR 18 CREATING THE CONDITIONS TRADE CHARTER FOR FAIR TRADE 06 THERE IS ANOTHER WAY 19 ACHIEVING INCLUSIVE ECONOMIC GROWTH 07 IMPORTANT NOTICE ON USE OF THIS CHARTER 19 PROVIDING DECENT WORK AND HELPING TO IMPROVE WAGES AND INCOMES 20 EMPOWERING WOMEN CHAPTER ONE 20 PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF CHILDREN AND INVESTING IN THE NEXT GENERATION 09 INTRODUCTION 21 NURTURING BIODIVERSITY AND THE ENVIRONMENT 10 BACKGROUND TO THE CHARTER 23 INFLUENCING PUBLIC POLICIES 10 OBJECTIVES OF THE CHARTER 23 INVOLVING CITIZENS IN BUILDING 11 FAIR TRADE’S VISION A FAIR WORLD 11 DEFINITION OF FAIR TRADE CHAPTER FOUR CHAPTER TWO 25 FAIR TRADE’S IMPACT AND ACHIEVEMENTS 13 THE NEED FOR FAIR TRADE 28 APPENDIX 29 NOTES Pebble Hathay Bunano AN OVERVIEW AN OVERVIEW AN OVERVIEW OF THE INTERNATIONAL FAIR TRADE CHARTER There is another way 02 03 AN OVERVIEW AN OVERVIEW “Fair Trade is based on modes of production THE RICHEST 1% NOW OWN AS MUCH WEALTH AS THE REST and trading that put people and planet before OF THE WORLD financial profit.” ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL FAIR TRADE CHARTER All over the world and for many cen- Trade actors explain how their work con- turies, people have developed econom- nects with the shared values and generic ic and commercial relations based on approach, and to help others who work mutual benefit and solidarity. -

Business Ethics: a Panacea for Reducing Corruption and Enhancing National Development

Nigerian Journal of Business Education (NIGJBED) Volume 5 No.2, 2018 BUSINESS ETHICS: A PANACEA FOR REDUCING CORRUPTION AND ENHANCING NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AKPANOBONG, UYAI EMMANUEL, Ph.D. Department of Vocational Education, Faculty of Education, University of Uyo Email:[email protected] Abstract In recent times there are scandals of unethical behaviours, corrupt practices, lack of accountability and transparency amongst public officials, political office holders, business managers and employees in the country. Therefore, there is an urgent need for public sector institutions to strengthen the ethics of their profession, integrity, honesty, transparency, confidentiality, and accountability in the public service. The paper further attempt to discuss the need for business ethics and some practices and behaviours which undermined the ethical behaviours of public official with strong emphasis on corruptions causes and preventions, conflicts of interest, consequences of unethical behaviour and resources management. The paper also outlined some measures on how to combat the evil called corruption in public service and business organizations. It is concluded that if all measures are taken into consideration the National Development may be achieved. Keywords: Ethics, unethical, transparency, accountability, corruption. Introduction In every business organization, there must be a laid down rules, values norms, order and other guiding principles which may be in form of ethics. The essence of this is to guide both the employer and the employees in achieving the organizational goals and at the same time help in checks and balances. Luanne (2017 saw ethics as the principles and values an individual uses to govern his activities and decisions. Therefore, Business Ethics could be described as that aspect of corporate governance that has to do with the moral values of managers encouraging them to be transparent in business dealing (Chienweike, 2010). -

Towards a Stakeholder-Shareholder Theory of Corporate Governance: a Comparative Analysis Katharine V

Hastings Business Law Journal Volume 7 Article 4 Number 2 Summer 2011 Summer 1-1-2011 Towards a Stakeholder-Shareholder Theory of Corporate Governance: A Comparative Analysis Katharine V. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_business_law_journal Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Katharine V. Jackson, Towards a Stakeholder-Shareholder Theory of Corporate Governance: A Comparative Analysis, 7 Hastings Bus. L.J. 309 (2011). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_business_law_journal/vol7/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Business Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS A STAKEHOLDER- SHAREHOLDER THEORY OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS Katharine V. Jackson* Most of the groups and individuals affected by the behavior of American public corporations do not have a voice in their governance. Just as governments retreat from regulating these entities, whether by political choice or as a result of globalization and regulatory arbitrage,1 stakeholders' 2 ability to shape corporate behavior themselves remains weak. Government empowers only one corporate stakeholder group- employees-to bargain with corporations for terms in their own interest. 1. See Eugene D. Genovese, Secularism in the General Crisis of Capitalism, 42 AM. J. JURIS. 195, 202 (1997) (multinational corporations are coming to control the "world economy, over which.,.. centralized national governments have less and less control."); Larry CatA Backer, Multinational Corporations, TransnationalLaw: The United Nations ' Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations as a Harbinger of Corporate Social Responsibility in International Law, 37 CoLUM. -

Comparing ESG and Value Added in European Companies

sustainability Article Stakeholder Value Creation: Comparing ESG and Value Added in European Companies Silvana Signori 1,* , Leire San-Jose 2,* , Jose Luis Retolaza 3 and Gianfranco Rusconi 4 1 Department of Management, University of Bergamo, 24127 Bergamo, Italy 2 Financial Economic II Department, University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU, 48015 Bilbao, Spain 3 Deusto Business School, University of Deusto, 48014 Bilbao, Spain; [email protected] 4 Department of Law, University of Bergamo, 24127 Bergamo, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (L.S.-J.) Abstract: In recent years, a renewed interest in value creation for stakeholders has been witnessed in different contexts. Different tools have been proposed to try to grasp and measure such value(s) but, in many cases, the main perspective remains that of the shareholders. To contribute to the field of research that aims to discuss novel ways of thinking about value creation measurement, this paper addresses the relationship between ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) ratings and Value Added, as proxies of value creation and distribution for stakeholders. In particular, we consider whether ESG ratings are able to capture companies that are characterized by their capacity for generating higher Value Added for stakeholders. Our analysis uses the frontier methodology combined with means comparison. Data from 2018 were downloaded from EIKON, for all companies within the Euro zone and for all sectors (1932 companies, of which 399 held an ESG rating, compared with 1533 without ESG analysis). Our analysis reveals that, although ESG is theoretically considered Citation: Signori, S.; San-Jose, L.; a good social responsibility proxy, ESG indices cannot be used as an indicator of value creation for Retolaza, J.L.; Rusconi, G. -

Suggestions from Social Accountability International

Suggestions from Social Accountability International (SAI) on the work agenda of the UN Working Group on Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises Social Accountability International (SAI) is a non-governmental, international, multi-stakeholder organization dedicated to improving workplaces and communities by developing and implementing socially responsible standards. SAI recognizes the value of the UN Working Group’s mandate to promote respect for human rights by business of all sizes, as the implementation of core labour standards in company supply chains is central to SAI’s own work. SAI notes that the UN Working Group emphasizes in its invitation for proposals from relevant actors and stakeholders, the importance it places not only on promoting the Guiding Principles but also and especially on their effective implementation….resulting in improved outcomes . SAI would support this as key and, therefore, has teamed up with the Netherlands-based ICCO (Interchurch Organization for Development) to produce a Handbook on How To Respect Human Rights in the International Supply Chain to assist leading companies in the practical implementation of the Ruggie recommendations. SAI will also be offering classes and training to support use of the Handbook. SAI will target the Handbook not just at companies based in Western economies but also at those in emerging countries such as Brazil and India that have a growing influence on the world’s economy and whose burgeoning base of small and medium companies are moving forward in both readiness, capacity and interest in managing their impact on human rights. SAI has long term relationships working with businesses in India and Brazil, where national companies have earned SA8000 certification and where training has been provided on implementing human rights at work to numerous businesses of all sizes.