Puerto Rican Queens’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cablefax Program Awards 2021 Winners and Nominees

March 31, 2021 SPECIAL ISSUE CFX Program Awards Honoring the 2021 Nominees & Winners PROGRAM AWARDS March 31, 2021 The Cablefax Program Awards has a long tradition of honoring the best programming in a particular content niche, regardless of where the content originated or how consumers watch it. We’ve recognized breakout shows, such as “Schitt’s Creek,” “Mad Men” and “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” long before those other award programs caught up. In this special issue, we reveal our picks for best programming in 2020 and introduce some special categories related to the pandemic. Read all about it! As an interactive bonus, the photos with red borders have embedded links, so click on the winner photos to sample the program. — Amy Maclean, Editorial Director Best Overall Content by Genre Comedy African American Winner: The Conners — ABC Entertainment Winner: Walk Against Fear: James Meredith — Smithsonian Channel This timely documentary is named after James Meredith’s 1966 Walk Against Fear, in which he set out to show a Black man could walk peace- fully in Mississippi. He was shot on the second day. What really sets this The Conners shines at finding ways to make you laugh through life’s film apart is archival footage coupled with a rare one-on-one interview with struggles, whether it’s financial pressures, parenthood, or, most recently, the Meredith, the first Black man to enroll at the University of Mississippi. pandemic. You could forgive a sitcom for skipping COVID-19 in its storyline, but by tackling it, The Conners shows us once again that life is messy and Nominees sometimes hard, but with love and humor, we persevere. -

Bob the Drag Queen and Peppermint's Star Studded “Black Queer Town Hall”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOB THE DRAG QUEEN AND PEPPERMINT’S STAR STUDDED “BLACK QUEER TOWN HALL” IS A REMINDER: BLACK QUEER PEOPLE GAVE US PRIDE Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Tiq Milan, Shea Diamond, Alex Newell, and Basit Among Participants NYC Pride and GLAAD to Support Three Day Virtual Event to Raise Funds for Black Queer Organizations and NYC LGBTQ Performers on June 19, 20, 21 New York, NY, Friday, June 12, 2020 – Advocates and entertainers Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen, today announced the “Black Queer Town Hall,” one of NYC Pride’s official partner events this year. NYC Pride and GLAAD, the global LGBTQ media advocacy organization, will stream the virtual event on YouTube and Facebook pages each day from 6:30-8pm EST beginning on Friday, June 19 and through Sunday, June 21, 2020. Performers and advocates slated to appear include Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Shea Diamond, Tiq Milan, Alex Newell, and Basit. Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen will host and produce the event. For a video featuring Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen and more information visit: https://www.gofundme.com/f/blackqueertownhall The “Black Queer Town Hall” will feature performances, roundtable discussions, and fundraising opportunities for #BlackLivesMatter, Black LGBTQ organizations, and local Black LGBTQ drag performers. The new event replaces the previously announced “Pride 2020 Drag Fest” and will shift focus of the event to center Black queer voices. During the “Black Queer Town Hall,” a diverse collection of LGBTQ voices will celebrate Black LGBTQ people and discuss pathways to dismantle racism and white supremacy. -

Tom Rubnitz / Dynasty Handbag

TOM RUBNITZ / DYNASTY HANDBAG 9/25/2012 PROGRAM: TOM RUBNITZ The Mother Show, video, 4 mins., 1991 Made for TV, video, 15 mins., 1984 Drag Queen Marathon, video, 5 mins., 1986 Strawberry Shortcut, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 Pickle Surprise, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 DYNASTY HANDBAG The Quiet Storm (with Hedia Maron), video, 10 mins., 2007 Eternal Quadrangle, video, 20 mins., 2012 WHITE COLUMNS JIBZ CAMERON JOSH LUBIN-LEVY What does it mean to be a great performer? In a rather conventional sense, great performing is often associated with a sense of interiority, becoming your character, identifying with your role. In that sense, a great performer could become anyone else simply by looking deep within herself. Of course, there’s a long history of performance practices that reject this model. Yet whether it is a matter of embracing or rejecting what is, so to speak, on the inside, there is an overarching belief that great performers are uniquely adept at locating themselves and using that self to build a world around them. It is no surprise then that today we are all expected to be great performers. Our lives are filled the endless capacity to shed one skin for another, to produce multiple cyber-personalities on a whim. We are hyperaware that our outsides are malleable and performative—and that our insides might be an endless resource for reinventing and rethinking ourselves (not to mention the world around us). So perhaps it’s almost too obvious to say that Jibz When I was a youth, say, about 8, I played a game in the Cameron, the mastermind behind Dynasty Handbag, is an incredible woods with my friend Ocean where we pretended to be hookers. -

Nicole Faulkner Welcome

Winter 2020 by Make-up Designory MUD grads win big at the Emmys® Catching up with LA Campus Instructor Stephen Dimmick Grads shining in the Hollywood spotlight From MUD to Pout— Beauty Business Maven Nicole Faulkner Welcome. I am excited to announce the first edition of our new quarterly magazine, Portraits. Since we founded MUD more than twenty years ago, we’ve been endlessly inspired by the ways in which our community of students, grads, instructors and friends has grown and thrived. Today, the MUD community spans the world, with an internationally diverse group of working artists in the fashion, entertainment, beauty and wedding industries. In Portraits, we’ll be celebrating groundbreaking work created by talented members of our community. I look forward to sharing it with you. TateTATE HOLLAND FOUNDER AND CEO, MAKE-UP DESIGNORY Your journey to a world of opportunity. Whether it’s backstage at Paris fashion week, on the red carpet in Hollywood, or heading up a freelance beauty business, we all enter this industry with dreams. When you study at Make-Up Designory (MUD), you can take the first step toward making them come true. MUD was founded as a school for make-up artists, by make-up artists. Today it’s evolved into much more. We offer an educational passport into the world of make-up for the film, television, fashion, beauty and wedding industries, with credits that are transferrable across our global network of MUD Campuses, Studios and Partner Schools. Start at one of our Campuses in Los Angeles or New York, or take a MUD- certified course at a MUD Studio or MUD Partner School closer to home. -

Thousands Unite in Golden Gate Park to Raise $1.8 Million for Aids Walk San Francisco

Contact: Cub Barrett, AIDS Walk San Francisco [email protected] c: (917) 385-2422 THOUSANDS UNITE IN GOLDEN GATE PARK TO RAISE $1.8 MILLION FOR AIDS WALK SAN FRANCISCO Community leaders, celebrities, and longtime supporters come together to raise critical funds and awareness SAN FRANCISCO, CA (July 15, 2018) – Ten thousand people gathered together on Sunday in Golden Gate Park for the 32nd annual AIDS Walk San Francisco (AWSF), both in support of people living with HIV/AIDS and to defend the dignity and equality of vulnerable populations everywhere. Walkers raised $1.814 million this year in support of ACRIA, PRC, and Project Open Hand, as well as dozens of other Bay Area HIV/AIDS service organizations. “AIDS Walk San Francisco provides us with the opportunity to not only show our support for those affected by HIV/AIDS, but to bring attention to the fact that people living with HIV/AIDS need unique services—especially as they age,” said Kelsey Louie, Executive Director of ACRIA. “We’re grateful that so many Bay Area folks came out to support the Walk, and that they continue to support the dozens of organizations throughout the region that are helping people make real progress in their lives.” The 10-kilometer Walk took place entirely within Golden Gate Park, with the start and finish lines at Robin Williams Meadow. The day began with the Macy’s Star Walker and VIP Breakfast, followed by the Macy’s Aerobic Warm-Up from the main stage led by fitness celebrity Bethany Meyers. At the Opening Ceremony, celebrities included Barrett Foa (NCIS: Los Angeles), Nico Tortorella (Younger), Dale Soules (Orange is the New Black), and longtime supporter ABC-7 news anchor Dan Ashley. -

Rupaul's Drag Race All Stars Season 2

Media Release: Wednesday August 24, 2016 RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE ALL STARS SEASON 2 TO AIR EXPRESS FROM THE US ON FOXTEL’S ARENA Premieres Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm Hot off the heels of one of the most electrifying seasons of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Mama Ru will return to the runway for RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 and, in a win for viewers, Foxtel has announced it will be airing express from the US from Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm on a new channel - Arena. In this second All Stars instalment, YouTube sensation Todrick Hall joins Carson Kressley and Michelle Visage on the judging panel alongside RuPaul for a season packed with more eleganza, wigtastic challenges and twists than Drag Race has ever seen. The series will also feature some of RuPaul’s favourite celebrities as guest judges, including Raven- Symone, Ross Matthews, Jeremy Scott, Nicole Schedrzinger, Graham Norton and Aubrey Plaza. Foxtel’s Head of Channels, Stephen Baldwin commented: “We know how passionate RuPaul fans are. Foxtel has been working closely with the production company, World of Wonder, and Passion Distribution and we are thrilled they have made it possible for the series to air in Australia just hours after its US telecast.” RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 will see 10 of the most celebrated competitors vying for a second chance to enter Drag Race history, and will be filled with plenty of heated competition, lip- syncing for the legacy and, of course, the All-Stars Snatch Game. The All Stars queens hoping to earn their place among Drag Race Royalty are: Adore Delano (S6), Alaska (S5), Alyssa Edwards (S5), Coco Montrese (S5), Detox (S5), Ginger Minj (S7), Katya (S7), Phi Phi O’Hara (S4), Roxxxy Andrews (S5) and Tatianna (S2). -

160 Emmy Photographs by Tommy Garcia/The Jude Group Grooming by Grace Phillips/State Management

Randy Barbato and Fenton Bailey 160 EMMY PHOTOGRAPHS BY TOMMY GARCIA/THE JUDE GROUP GROOMING BY GRACE PHILLIPS/STATE MANAGEMENT FOR MORE THAN A QUARTER-CENTURY, RANDY BARBATO AND FENTON BAILEY’S WORLD OF WONDER HAS TACKED CLOSELY TO THE CULTURAL ZEITGEIST, EMBRACING — AS BAILEY PUTS IT — “THE UNEXAMINED AND THE UNCONSIDERED.” SAYS BARBATO: “OUR WORK TYPICALLY HAS A CONNECTION TO PEOPLE WHO FEEL MARGINALIZED OR JUDGED.” BY MICHAEL GOLDMAN TelevisionAcademy.com 161 USHING INTO THE CONFERENCE ROOM ON THE TOP FLOOR OF THE 1930S ART DECO BUILDING THEY OWN ON HOLLYWOOD BOULEVARD, RANDY BARBATO AND FENTON BAILEY APOLOGIZE FOR THEIR LATENESS. THEY’VE JUST COME FROM THE EDIT ROOM, WHERE THEY LOCKED THE FINAL CUT OF MENENDEZ: BLOOD BROTHERS, A TV MOVIE THEY COPRODUCED AND CODIRECTED FOR A JUNE DEBUT ON LIFETIME. Blood Brothers is one of hundreds of projects made by World of Won- English television. That show explored the camcorder revolution, building on der, the production company they have jointly operated since 1991. Bailey a theme that helped launch Barbato and Bailey’s producing careers. and Barbato have flourished by crossing genres and media platforms, and by Fascinated by New York public-access television, the duo created their spotlighting extreme and often controversial topics, including tabloid news, first TV show, Manhattan Cable, out of public-access clips in 1991. It was a gender roles, LGBT issues and, more generally, almost all aspects of human hit in the U.K. and led to more programs there, like the one that eventually sexuality. earned Nevins’s attention. She hired them in 1993 to produce HBO’s Shock “Sex is the engine or driving force of who humans are,” Bailey says. -

BOOK NOTES 6/14/2021 Who Is Rupaul? by Nico Medina Call

BOOK NOTES 6/14/2021 Who is RuPaul? by Nico Medina Call Number: 921 RUPAUL RuPaul Andre Charles always knew he was meant to be a performer. Ru developed his drag- queen personality and launched his career in the 1980s. He now hosts and judges the widely popular and long-running show RuPaul's Drag Race, which has raised the profile of the art of drag, and drag queens around the world. Sincerely, Your Autistic Child by Emily Paige Ballou, Sharon daVanport, and Morénike Giwa Onaiwu Call Number: 618.92 BALLOU Sincerely, Your Autistic Child represents an authentic resource for parents written by people who understand this experience most, autistic people themselves. Tackles the everyday challenges of growing up while honestly addressing the emotional needs, sensitivity, and vibrancy of autistic girls and nonbinary people. Plunder by Menachem Kaiser Call Number: 940.53 KAISER Kaiser takes up his Holocaust-survivor grandfather’s former battle to reclaim the family’s apartment building in Sosnowiec, Poland. He makes a discovery that his grandfather’s cousin wrote a secret memoir while a slave laborer in a vast, secret Nazi tunnel complex. A band of Silesian treasure seekers revere the memoir as the guidebook to Nazi plunder. Every Day is a Gift by Tammy Duckworth Call Number: 328.73 DUCKWORTH Learn the incredible story of Illinois senator and Iraq War veteran Tammy Duckworth and see what inspired her to follow the path that made her who she is today. The book traces her impoverished childhood, her decision to join the Army, the months spent recovering from the RPG attack that shot down her helicopter and nearly took her life, and her subsequent mission of serving in elected office. -

Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from Rupaul's Drag Race

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 3 Feminist Comforts and Considerations amidst a Global Pandemic: New Writings in Feminist and Women’s Studies—Winning and Article 3 Short-listed Entries from the 2020 Feminist Studies Association’s (FSA) Annual Student Essay Competition May 2020 Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race Phoebe Chetwynd Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chetwynd, Phoebe (2020). Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(3), 22-35. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss3/3 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race By Phoebe Chetwynd1 Abstract The popularity of the reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race is often framed as evidence of Western societies’ increasing tolerance towards queer identities. This paper instead considers the ideological cost of this mainstream success, arguing that the show does not successfully challenge dominant heteronormative values. In light of Rosalind Gill’s work on postfeminism, it will be argued that the show’s format calls upon contestants (and viewers) to conform to a postfeminist ideal that valorises normative femininity and reaffirms the gender binary. -

U Au S a Ace As

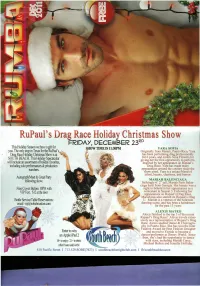

u au s a ace i ay C is as F'RIDAY, DECEM13ER 23RD This Holiday Season we have a gift for SHOW TIME IS 11:30PM YARA SOFIA you. The only stop in Texas for the'RuPaul' s Originally from Manati, Puerto Rico, Yara Drag Race HolieayChris1mas Show is at has been performing drag professionally for 6 years, and credits Nina Flowers for sourn BEACH. This Holiday S~cu1ar giving her the first opportunity to perform. will include an assortment of holiday favorites, Inspired by her appearance on Rupaul's including solo performances & production Drag Race, Yara has made many numbers. appearances around the country since the show aired. Yara is a unique blend of talent, beauty, charisma, and humor. AutographIMeet & Greet Party MARIAH BALENCIAGA following show. Strikingly 6' 2" tall, Mariah Paris Balen- ciaga hails from Georgia. Her beauty was a Free Cover Before 10PM with sight to behold in her appearances as a VIPText. $12 atthe door contestant in Season 3. Following her appearances on Rupaul' s Drag Race, Mariah has also starred on Rupaul's Drag Bottle ServicelTable Reservations: U. Mariah is a veteran of the ballroom email [email protected] dancing scene, and has been a hairdresser for the past 13 years. ALEXIS MATEO Alexis finished in the top 3 of the recent Rupaul's Drag Race! Alexis travels exten- sively as a representative ofRupaul's Drag Race. Alexis studied Dance & Choreogra- phy in Puerto Rico. She has won the Inter Fashion Award for Best Fashion Designer Enter to win and moved to Florida to become a an Apple iPad2 dancer/performer at Disney World. -

Viacomcbs Celebrates 66 Primetime Emmy Award Nominations

ViacomCBS Celebrates 66 Primetime Emmy Award Nominations July 14, 2021 CBS Television Network, CBS Studios and Paramount+ Score 35 Total Nominations Stephen Colbert’s The Late Show, The Election Night Special and Tooning Out the News Receive 9 Nominations, the Most of Any Late Night Brand ViacomCBS’ MTV Entertainment Group Earns 20 Nominations, Including First-Time Nominations for Paramount Network’s “Yellowstone” and MTV Documentary Films’ “76 Days” SHOWTIME® Receives Six Nominations, Including “Shameless” star William H. Macy for Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series LOS ANGELES--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jul. 13, 2021-- ViacomCBS earned 66 Academy of Television Arts & Sciences 73rd Primetime Emmy Award nominations across its combined portfolio. CBS Television Network, CBS Studios and Paramount+ together received a total of 35 Primetime Emmy nominations. CBS’ “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” – the #1 late night talk show on television – received five nominations, marking the series’ 18th Emmy nomination to date. CBS landed several nominations for talent and special programming, including “Oprah With Meghan And Harry: A CBS Primetime Special” and “John Lewis: Celebrating A Hero.” “The Pepsi Super Bowl LV Halftime Show Starring The Weeknd” and “The 63rd Annual Grammy Awards” also received multiple nods this year. For her starring role in “Mom,” Allison Janney was nominated for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. CBS Studios received 21 nominations, among them an Outstanding Competition Series nod for “The Amazing Race.” Short-form series “Carpool Karaoke: The Series” was also nominated. Paramount+, together with CBS Studios, picked up six nominations this season, including four nominations for “Star Trek: Discovery.” “Star Trek: Lower Decks'' and “Stephen Colbert Presents Tooning Out the News'' each received their first-ever Emmy nominations. -

Feminist Media Studies “She Is Not Acting, She

This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Berkeley] On: 06 January 2014, At: 10:16 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Feminist Media Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 “She Is Not Acting, She Is” Sabrina Strings & Long T. Bui Published online: 27 Aug 2013. To cite this article: Sabrina Strings & Long T. Bui , Feminist Media Studies (2013): “She Is Not Acting, She Is”, Feminist Media Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2013.829861 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2013.829861 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.