Drag Language Translation on Rupaul's Drag Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trixie Mattel and Katya Dating

UNHhhh ep 5: "Dating PART 2" with Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 4: "Dating" with Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 3: "Traveling" w/ Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 2: "RDR8 Cast Advice" w/ Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. 1 day ago · Trixie and Katya are back with new episodes of UNHhhh Season 5 and they've got the trailer to prove it. Here's everything you need to know about Trixie and Katya. Trixie Mattel is the stage name of Brian Firkus, a drag queen, performer, comedian and music artist best known as a Season 7 contestant of RuPaul's Drag Race and the winner of All Stars Following the success she got thanks to the show, Trixie started presenting a web show with Katya, entitled "UNHhhh", on the WOWPresents' YouTube renuzap.podarokideal.ru later starred on their new show entitled . Jul 15, · Katya: Paint on a different one! Trixie Mattel: This is a window for you, Carolyn, to become the new hot girl in the office right under everyone’s noses. Because you watched a few makeup. Mar 27, · Ever since Katya Zamolodchikova returned to Twitter, fans have been anxiously awaiting to see if the drag star would say anything about her friend and former co-star Trixie Mattel’s win on. Mar 24, · — Trixie Mattel (@trixiemattel) December 20, Trixie hasn’t revealed much about her boyfriend. She protects him from social media users as well. Trixie Mattel Net Worth and TV shows. The drag queen, Trixie Mattel has an estimated net worth of $2 million. Trixie started performing drag in the year at LaCage NiteClub. -

Fatima Mechtab, There Is Only One Remedy: More Mocktails!

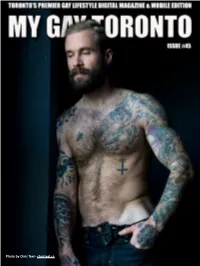

MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Photo by Chris Teel - christeel.ca My Gay Toronto page: 1 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 2 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 3 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 4 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Alaska Thunderfuck and Bianca Del Rio werq the queens who Werq the World RAYMOND HELKIO Queens Werq the World is coming to the Danforth Music Hall on Friday May 26, 2017. Get your tickets early because a show this epic only comes around once in a while. Alaska Thunderfuck, Alys- sa Edwards, Detox, Latrice Royale and Shangela, plus from season nine of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Aja, Peppermint, Sasha Velour and Trinity Taylor. Shangela recently told Gay Times Magazine “This is the most outrageous and talented collection of queens that have ever toured together. We’re calling this the Werq the World tour because that’s exactly what these Drag Race stars will be doing for fans: Werqing like they’ve never Werqued it before!” I caught up with Alaska and Bianca to get the dish on the upcoming show and the state of drag. My Gay Toronto page: 5 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 What is the most loving thing you’ve ever seen another contestant on RDR do? Alaska: Well I do have to say, when I saw Bianca hand over her extra waist cincher to Adore, I was very mesmerized by the compassion of one queen helping out another, and Drag Race is such a competitive competition and you always want the upper hand, I think that was so mething so genuine and special. -

Cablefax Program Awards 2021 Winners and Nominees

March 31, 2021 SPECIAL ISSUE CFX Program Awards Honoring the 2021 Nominees & Winners PROGRAM AWARDS March 31, 2021 The Cablefax Program Awards has a long tradition of honoring the best programming in a particular content niche, regardless of where the content originated or how consumers watch it. We’ve recognized breakout shows, such as “Schitt’s Creek,” “Mad Men” and “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” long before those other award programs caught up. In this special issue, we reveal our picks for best programming in 2020 and introduce some special categories related to the pandemic. Read all about it! As an interactive bonus, the photos with red borders have embedded links, so click on the winner photos to sample the program. — Amy Maclean, Editorial Director Best Overall Content by Genre Comedy African American Winner: The Conners — ABC Entertainment Winner: Walk Against Fear: James Meredith — Smithsonian Channel This timely documentary is named after James Meredith’s 1966 Walk Against Fear, in which he set out to show a Black man could walk peace- fully in Mississippi. He was shot on the second day. What really sets this The Conners shines at finding ways to make you laugh through life’s film apart is archival footage coupled with a rare one-on-one interview with struggles, whether it’s financial pressures, parenthood, or, most recently, the Meredith, the first Black man to enroll at the University of Mississippi. pandemic. You could forgive a sitcom for skipping COVID-19 in its storyline, but by tackling it, The Conners shows us once again that life is messy and Nominees sometimes hard, but with love and humor, we persevere. -

“Rupaul's Drag Race” Season Nine Premiere!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: SOUTH FLORIDA’S VERY OWN THE GRAND RESORT AND SPA IS A NEW PROUD SPONSOR OF VH1’S “RUPAUL'S DRAG RACE” SEASON NINE PREMIERE! FORT LAUDERDALE, FL – Saturday, March 25, 2017: RuPaul’s Drag Race kicked off their season nine premiere on VH1 on Friday, March 24th at 8:00 pm EST. During its first episode, Emmy Awarder Winner, RuPaul awarded contestant, Nina Bo’nina Brown, a trip to Fort Lauderdale Beach’s, The Grand Resort and Spa. The prize included a one week stay, for two, in the 2 bedroom, 2 bathroom Grand Penthouse that boasts an 800 square foot private, ocean view terrace with a Jacuzzi and outdoor shower. Also included in this prize package will be airfare for two, and a complimentary massage and facial. The total prize value of $6,000. Casey Koslowski, Proprietor of The Grand, states that he looks forward to seeing Nina and his guest, at his award- winning spa-resort and sunning themselves on Fort Lauderdale Beach very soon! The Grand Resort and Spa is Fort Lauderdale’s premiere gay-owned and operated men’s spa- resort that first opened in 1999. With 33 well-appointed rooms and suites, it is located just steps from the beach and convenient to all of Fort Lauderdale’s attractions and nightlife. As Fort Lauderdale’s first gay resort with its own full-service day spa and hair studio, they offer guests an experience that is unique and wonderfully indulgent. From a relaxing Swedish massage to a haircut before your night on the town, the talented staff can accommodate all your needs – guaranteed to “Exceed Expectations.” A sample of the property’s awards and accolades include “Certificate of Excellence, Hall of Fame” – TripAdvisor; “Editor’s Choice” – Man About World; “#1 in Fort Lauderdale” – Pink Choice Award; "Best Small Hotel or Resort in the World" - Out Traveler Award Winner; "Top 10 Resorts" - The Travel Channel; "One of the top 10 gay-owned spas in the United States" – Out Traveler Magazine; “USA TODAY 10 BEST” – USA TODAY. -

Bob the Drag Queen and Peppermint's Star Studded “Black Queer Town Hall”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOB THE DRAG QUEEN AND PEPPERMINT’S STAR STUDDED “BLACK QUEER TOWN HALL” IS A REMINDER: BLACK QUEER PEOPLE GAVE US PRIDE Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Tiq Milan, Shea Diamond, Alex Newell, and Basit Among Participants NYC Pride and GLAAD to Support Three Day Virtual Event to Raise Funds for Black Queer Organizations and NYC LGBTQ Performers on June 19, 20, 21 New York, NY, Friday, June 12, 2020 – Advocates and entertainers Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen, today announced the “Black Queer Town Hall,” one of NYC Pride’s official partner events this year. NYC Pride and GLAAD, the global LGBTQ media advocacy organization, will stream the virtual event on YouTube and Facebook pages each day from 6:30-8pm EST beginning on Friday, June 19 and through Sunday, June 21, 2020. Performers and advocates slated to appear include Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Shea Diamond, Tiq Milan, Alex Newell, and Basit. Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen will host and produce the event. For a video featuring Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen and more information visit: https://www.gofundme.com/f/blackqueertownhall The “Black Queer Town Hall” will feature performances, roundtable discussions, and fundraising opportunities for #BlackLivesMatter, Black LGBTQ organizations, and local Black LGBTQ drag performers. The new event replaces the previously announced “Pride 2020 Drag Fest” and will shift focus of the event to center Black queer voices. During the “Black Queer Town Hall,” a diverse collection of LGBTQ voices will celebrate Black LGBTQ people and discuss pathways to dismantle racism and white supremacy. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Kimmel Center Cultural Campus Presents Critically-Acclaimed Drag Theatre Show Spectacular Sasha Velour's Smoke & Mirrors

Tweet It! Drag icon @Sasha_Velour’s revolutionary show “Smoke & Mirrors” will be at the @KimmelCenter on 11/12. The effortless blend of drag, visual art, and magic is a can’t-miss! More info @ kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Lauren Woodard Jessica Christopher 215-790-5835 267-765-3738 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER CULTURAL CAMPUS PRESENTS CRITICALLY-ACCLAIMED DRAG THEATRE SHOW SPECTACULAR SASHA VELOUR’S SMOKE & MIRRORS, COMING TO THE MERRIAM THEATER NOVEMBER 12, 2019 "Smoke & Mirrors is a spellbinding tour de force." - Forbes “The intensely personal [Smoke & Mirrors] shows what a top-of-her-game queen Velour really is, both as an artist and as a storyteller.” - Paper Magazine "[Velour’s] most spectacular stage gambit yet." - Time Out New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, October 9, 2019) – Sasha Velour’s Smoke & Mirrors, the critically-acclaimed one-queen show by global drag superstar and theatre producer, Sasha Velour, will come to the Kimmel Center Cultural Campus’ Merriam Theater on November 12, 2019 at 8:00 p.m., as part of the show’s 23-city North American tour. This is Velour’s first solo tour, following her win of RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 9, and sold-out engagements of Smoke & Mirrors in New York City, Los Angeles, London, Australia, and New Zealand this year. “Sasha Velour is a drag superstar, as well as an astonishing talent in the visual arts,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Smoke & Mirrors invites audiences to experience the depths of Velour that have yet to be explored in the public eye. -

Tom Rubnitz / Dynasty Handbag

TOM RUBNITZ / DYNASTY HANDBAG 9/25/2012 PROGRAM: TOM RUBNITZ The Mother Show, video, 4 mins., 1991 Made for TV, video, 15 mins., 1984 Drag Queen Marathon, video, 5 mins., 1986 Strawberry Shortcut, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 Pickle Surprise, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 DYNASTY HANDBAG The Quiet Storm (with Hedia Maron), video, 10 mins., 2007 Eternal Quadrangle, video, 20 mins., 2012 WHITE COLUMNS JIBZ CAMERON JOSH LUBIN-LEVY What does it mean to be a great performer? In a rather conventional sense, great performing is often associated with a sense of interiority, becoming your character, identifying with your role. In that sense, a great performer could become anyone else simply by looking deep within herself. Of course, there’s a long history of performance practices that reject this model. Yet whether it is a matter of embracing or rejecting what is, so to speak, on the inside, there is an overarching belief that great performers are uniquely adept at locating themselves and using that self to build a world around them. It is no surprise then that today we are all expected to be great performers. Our lives are filled the endless capacity to shed one skin for another, to produce multiple cyber-personalities on a whim. We are hyperaware that our outsides are malleable and performative—and that our insides might be an endless resource for reinventing and rethinking ourselves (not to mention the world around us). So perhaps it’s almost too obvious to say that Jibz When I was a youth, say, about 8, I played a game in the Cameron, the mastermind behind Dynasty Handbag, is an incredible woods with my friend Ocean where we pretended to be hookers. -

Nicole Faulkner Welcome

Winter 2020 by Make-up Designory MUD grads win big at the Emmys® Catching up with LA Campus Instructor Stephen Dimmick Grads shining in the Hollywood spotlight From MUD to Pout— Beauty Business Maven Nicole Faulkner Welcome. I am excited to announce the first edition of our new quarterly magazine, Portraits. Since we founded MUD more than twenty years ago, we’ve been endlessly inspired by the ways in which our community of students, grads, instructors and friends has grown and thrived. Today, the MUD community spans the world, with an internationally diverse group of working artists in the fashion, entertainment, beauty and wedding industries. In Portraits, we’ll be celebrating groundbreaking work created by talented members of our community. I look forward to sharing it with you. TateTATE HOLLAND FOUNDER AND CEO, MAKE-UP DESIGNORY Your journey to a world of opportunity. Whether it’s backstage at Paris fashion week, on the red carpet in Hollywood, or heading up a freelance beauty business, we all enter this industry with dreams. When you study at Make-Up Designory (MUD), you can take the first step toward making them come true. MUD was founded as a school for make-up artists, by make-up artists. Today it’s evolved into much more. We offer an educational passport into the world of make-up for the film, television, fashion, beauty and wedding industries, with credits that are transferrable across our global network of MUD Campuses, Studios and Partner Schools. Start at one of our Campuses in Los Angeles or New York, or take a MUD- certified course at a MUD Studio or MUD Partner School closer to home. -

Un Reality Para Los Que Entienden Y Los Que No

Un reality para los que entienden y los que no El programa RuPaul’s Drag Race y su contexto lingüístico: la dificultad de traducir el vocabulario drag y los juegos de palabras Arnau Pérez i Sampietro Tutor: Patrick Zabalbeascoa Terran Seminario 204: Traducció audiovisual Curso 2017-2018 Abstract This project aims to show different aspects that should be taken into account when translating a TV show like RuPaul’s Drag Race, a show because of the specific vocabulary of a subculture inside the LGBT minority, and because of its use of puns and sense of humour. As an introduction, a small explanation of what the program is about, its context in the USA society and its current fame are given, as well as a consideration about key aspects to be taken into account before getting into the translation. These include the thought process of deciding whether to use subtitles or dubbing, gender treatment of drag queen contestants, the presence of humour, and humour aspects behind what is said and how to make it possible for a Spanish-speaking person to understand them. After that, a small analysis of existing translations of the show into Spanish is presented. The most important aspect of this study is the translation we propose of different elements of the show. These translations are divided in three categories, including: typical slang used by drag queens on or off the show; specific phraseology that originated or has been popularised by the show; and puns extracted from the show. The translation options are followed by an explanation of the translation process, taking into account the fact that it should be as comprehensible as it is to an English viewer of the show but it also has to make a Spanish viewer laugh as much. -

On the Purple Circuit with Bill Kaiser Volume 9, Number 1 the SIDNEY MORRIS ISSUE

On The Purple Circuit With Bill Kaiser Volume 9, Number 1 THE SIDNEY MORRIS ISSUE WELCOME TO ON THE PURPLE CIRCUIT! An ongoing issue is censorship of the arts. CORPUS CHRISTI is an example with the outrageous imposition of a We exist to promote GLQBT theatre and performance fatwah against Terrence McNally after the London throughout the world and invite you to join in that endeavor! production. Also closer to home was the difficulty that Daylight Zone had in finding a space for their production- This is the Sidney Morris Issue. Sidney is one of our pioneer Kudos to Theatre Double in Philadelphia for providing space! Gay playwrights. Based in New York his plays are part of our culture and still available for production. While in poor health, Lastly I want to speak again about the treatment of he is still writing and has an important message for Playwrights. We would have no productions without them. I producers in his article DO US! in this issue. He also is the really feel that PC theatres have to be as responsible as first interviewee of my Oral History Project and I thank him straight ones about scripts. If you have a staff shortage-find for that (as well as Tom O'Neil who did the interview and Ty some volunteers to either read for you or send unsolicited Wilson who did the camerawork). scripts back in their SASEs in a reasonable length of time. I know that Producers have their share of woes too and we all As you know I believe in theatre and activism. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Tufts Dining Workers and Students Are Pictured Marching in the ‘Picket for a Fair Dining Contract’ on March 5

WOMEN’S LACROSSE Work-study students discuss pressures, commitments see FEATURES / PAGE 4 Jumbos put on offensive clinic in win over Continentals A call for trustee transparency SEE SPORTS/BACK PAGE see OPINION/ PAGE 10 THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF TUFTS UNIVERSITY EST. 1980 HE UFTS AILY VOLUME LXXVII, ISSUE 30T T D MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, MASS. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 6, 2019 tuftsdaily.com More than 800 people attend picket for dining workers, strike vote set for March 14 KYLE LUI / THE TUFTS DAILY Tufts Dining workers and students are pictured marching in the ‘Picket for a Fair Dining Contract’ on March 5. by Alexander Thompson “Tufts University can afford for one job He said the university hopes to resolve the situ- Trisha O’Brien, a dining services atten- Assistant News Editor to be enough for all workers. It was never ation as soon as possible. dant at Kindlevan Café who held the banner a question of affordability, it’s a question of The dining workers first began their negoti- at the head of the procession as it moved to In a dramatic development in their sev- respect for human dignity,” Lang told the ations with Tufts in August 2018. Dewick-MacPhie Dining Center, said that she en-month campaign for a contract with crowd through a megaphone. “This admin- In an email to the Daily after the latest would vote for the the strike because she the university, Tufts Dining workers will istration is getting increasingly isolated on round of negotiations on Feb. 27, Mike Kramer, thinks negotiations are not going well, and a vote on whether to go on strike on March this campus and in the communities around the lead negotiator for UNITE HERE Local 26, strike is necessary in order for the workers to 14, according to UNITE HERE Local 26 this campus.” wrote that the sticking points were key eco- secure a fair contract.