Turkish World Music: Multiple Fusions and Authenticities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lista MP3 Por Genero

Rock & Roll 1955 - 1956 14668 17 - Bill Justis - Raunchy (Album: 247 en el CD: MP3Albms020 ) (Album: 793 en el CD: MP3Albms074 ) 14669 18 - Eddie Cochran - Summertime Blues 14670 19 - Danny and the Juniors - At The Hop 2561 01 - Bony moronie (Popotitos) - Williams 11641 01 - Rock Around the Clock - Bill Haley an 14671 20 - Larry Williams - Bony Moronie 2562 02 - Around the clock (alrededor del reloj) - 11642 02 - Long Tall Sally - Little Richard 14672 21 - Marty Wilde - Endless Sleep 2563 03 - Good golly miss molly (La plaga) - Bla 11643 03 - Blue Suede Shoes - Carl Perkins 14673 22 - Pat Boone - A Wonderful Time Up Th 2564 04 - Lucile - R Penniman-A collins 11644 04 - Ain't that a Shame - Pat Boone 14674 23 - The Champs - Tequila 2565 05 - All shock up (Estremecete) - Blockwell 11645 05 - The Great Pretender - The Platters 14675 24 - The Teddy Bears - To Know Him Is To 2566 06 - Rockin' little angel (Rock del angelito) 11646 06 - Shake, Rattle and Roll - Bill Haley and 2567 07 - School confidential (Confid de secund 11647 07 - Be Bop A Lula - Gene Vincent 1959 2568 08 - Wake up little susie (Levantate susani 11648 08 - Only You - The Platters (Album: 1006 en el CD: MP3Albms094 ) 2569 09 - Don't be cruel (No seas cruel) - Black 11649 09 - The Saints Rock 'n' Roll - Bill Haley an 14676 01 - Lipstick on your collar - Connie Franci 2570 10 - Red river rock (Rock del rio rojo) - Kin 11650 10 - Rock with the Caveman - Tommy Ste 14677 02 - What do you want - Adam Faith 2571 11 - C' mon everydody (Avientense todos) 11651 11 - Tweedle Dee - Georgia Gibbs 14678 03 - Oh Carol - Neil Sedaka 2572 12 - Tutti frutti - La bastrie-Penniman-Lubin 11652 12 - I'll be Home - Pat Boone 14679 04 - Venus - Frankie Avalon 2573 13 - What'd I say (Que voy a hacer) - R. -

Tarkan Free Songs

Tarkan free songs click here to download Watch videos & listen free to Tarkan: Yolla, Simarik & more. popularly known as Tarkan, is a successful World Music award-winning pop music Top Tracks. Free download Download Tarkan Songs mp3 for free. TARKAN - Dudu. Source: TARKAN - Kuzu Kuzu (Original). Source: TARKAN - Simarik With Lyrics. Tarkan Songs Download- Listen Tarkan MP3 songs online free. Play Tarkan album songs MP3 by Tarkan and download Tarkan songs on www.doorway.ru "Simarik" made him an overnight success in European clubs and led to a wider release of his self- titled album from that year. Tarkan included songs from his. Mp3 Free Download. Free download Tarkan Kiss Kiss Turkish Mp3 Free Download mp3 for free TARKAN - Dudu. Source: youtube. Play Stop Tarkan - Şımarık - Simarik- Kiss Kiss (Extended Version) Original Video. Source: youtube. Free download Kiss Kiss Tarkan Mp3. To start this download lagu Remember that by downloading this song you accept our terms and Filename: TARKAN - www.doorway.ru3 Filename: Zumba Simarik Tarkan Kiss www.doorway.ru3. Download Tarkan songs in mp3 format from our multi category Music databases. Free Mp3 Download Tarkan – İnci Tanem karaoke Tarkan – Dudu. Listen Tarkan songs online without any payments! MusicMegaBox give you free access to all the best and new Tarkan songs from any device: PC, Android. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from DJ Tarkan on your desktop or mobile device. DJ Tarkan & V-Sag - Paragalo (Original Mix) [FREE DOWNLOAD]. Unlimited free Tarkan music - Click to play Sikidim, Bu Gece (club remix) and whatever else you want! Tarkan Tevetoğlu (born October 17, in Alzey, West. -

Folk/Värld: Europa

Kulturbibliotekets vinylsamling: Folk/Världsmusik: Europa Samlingar F 2269 ASIEN (s) Dances of the world's peoples vol. 4 (Grekland, Turkiet, Israel, Armenien ) F 2269 EUROPA (s) Dances of the world's peoples vol. 4 (Grekland, Turkiet, Israel, Armenien ) F 2269 GREKLAND (s) Dances of the world's peoples vol. 4 (Grekland, Turkiet, Israel, Armenien ) F 2270 Europa Dances of the world's people vol 1: Grekland, Rumänien, Bulgarien, Makedonien. Albanien F 4248 ALBANIEN (s) Folk music of Albania F 5837 ALBANIEN (s) Folkdanser från norra Albanien (Pllake me kenge dhe muzike shqiptare) F 5836 ALBANIEN (s) Folksånger från Albanien F 5835 ALBANIEN (s) Folksånger från Albanien F 5834 ALBANIEN (s) Folksånger från Albanien F 5838 ALBANIEN (s) Folksånger från mellersta Albanien F 5839 ALBANIEN (s) Folksånger från norra Albanien F 5833 ALBANIEN (s) Folksånger från norra Albanien F 5832 ALBANIEN (s) Folksånger från norra Albanien och Peshkopiatrakten F 5831 ALBANIEN (s) Kärlekssånger från mellersta Albanien F 5840 ALBANIEN (s) Nutida populära sånger med motiv från dagens Albanien F 5841 ALBANIEN (s) Nutida sånger med motiv från dagens Albanien F 5842 ALBANIEN (s) Populära sånger från dagens Albanien F 3784 ALBANIEN (s) Songs and dances of Albania (Orchestra of Radio Pristina) Armenien F 4853 ARMENIEN (s) Armenien (Armenie, Musique de tradition populaire) F 4784 ARMENIEN (s) Medeltida liturgisk sång från Armenien F 2269 ASIEN (s) Dances of the world's peoples vol. 4 (Grekland, Turkiet, Israel, Armenien ) F 2269 EUROPA (s) Dances of the world's peoples vol. 4 (Grekland, Turkiet, Israel, Armenien ) F 2269 GREKLAND (s) Dances of the world's peoples vol. -

White Woman Draft

SKYROS CARNIVAL SKYROS CARNIVAL Photographs by Dick Blau Essay by Agapi Amanatidis and Panayotis Panopoulos Audio CD and Video DVD by Steven Feld VOXLOX 3 DICK I I grew up in the theater, my father a director and my mother an actress. As a result, I devel - oped a lifelong fascination with the dramatic moment, the heightened gesture, the mysterious transfor - mation of self into other. I suppose it was inevitable that my abiding preoccupation with the stage would find its way into my photography. When Steve called one day a few years ago and told me that Panos had told him about Greece’s wildest and noisiest carnival, I put down the phone and began packing my bag and cameras. What I eventually discovered on Skyros was not exactly what I spent the next few months imagining. I had been dreaming of Dionysus, Pan, and the Eleusinian mysteries in a smoky grove, but I found myself instead in a small Greek island town with an Internet café. Normal life continued amidst the wildness. Performers and audience were mixed together. And then there were the cameras. Everyone, it seemed, was either taking pictures or posing for them. This was not simply an ancient ritual; it was a modern media event. In fact, the carnival was old and new at the same time. Skyros carnival is a hybrid form in which the goat dancers, dressed in their rough, rank animal skins and festooned in huge clanking bells, mix easily with other performers who look decidedly of our moment. I would be standing at dusk on the street waiting for the dancers to appear when a kid would float by wearing a cheap monkey mask from the grocery store, and I would instantly find myself swept up with him into the world of myth. -

The Balkans of the Balkans: the Meaning of Autobalkanism in Regional Popular Music

arts Article The Balkans of the Balkans: The Meaning of Autobalkanism in Regional Popular Music Marija Dumni´cVilotijevi´c Institute of Musicology, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] Received: 1 April 2020; Accepted: 1 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: In this article, I discuss the use of the term “Balkan” in the regional popular music. In this context, Balkan popular music is contemporary popular folk music produced in the countries of the Balkans and intended for the Balkan markets (specifically, the people in the Western Balkans and diaspora communities). After the global success of “Balkan music” in the world music scene, this term influenced the cultures in the Balkans itself; however, interestingly, in the Balkans themselves “Balkan music” does not only refer to the musical characteristics of this genre—namely, it can also be applied music that derives from the genre of the “newly-composed folk music”, which is well known in the Western Balkans. The most important legacy of “Balkan” world music is the discourse on Balkan stereotypes, hence this article will reveal new aspects of autobalkanism in music. This research starts from several questions: where is “the Balkans” which is mentioned in these songs actually situated; what is the meaning of the term “Balkan” used for the audience from the Balkans; and, what are musical characteristics of the genre called trepfolk? Special focus will be on the post-Yugoslav market in the twenty-first century, with particular examples in Serbian language (as well as Bosnian and Croatian). Keywords: Balkan; popular folk music; trepfolk; autobalkanism 1. -

MEVLANA JALALUDDİN RUMİ and SUFISM

MEVLANA JALALUDDİN RUMİ and SUFISM (A Dervish’s Logbook) Mim Kemâl ÖKE 1 Dr. Mim Kemâl ÖKE Mim Kemal Öke was born in Istanbul in 1955 to a family with Central Asian Uygur heritage. Öke attended Şişli Terakki Lyceum for grade school and Robert College for high school. After graduating from Robert College in 1973, he went to England to complete his higher education in the fields of economics and history at Cambridge University. He also specialized in political science and international relations at Sussex, Cambridge, and Istanbul universities. In 1979 he went to work at the United Nation’s Palestine Office. He returned to Turkey in 1980 to focus on his academic career. He soon became an assistant professor at Boğaziçi University in 1984 and a professor in 1990. In 1983, TRT (Turkish Radio and Television Corporation) brought Öke on as a general consulting manager for various documentaries, including “Voyage from Cadiz to Samarkand in the Age of Tamerlane.” Up until 2006 he was involved in game shows, talk shows, news programs and discussion forums on TRT, as well as on privately owned channels. He also expressed his evaluations on foreign policy in a weekly syndicated column, “Mim Noktası” (Point of Mim). Though he manages to avoid administrative duties, he has participated in official meetings abroad on behalf of the Turkish Foreign Ministry. Throughout his academic career, Öke has always prioritized research. Of his more than twenty works published in Turkish, English, Urdu and Arabic, his writings on the issues of Palestine, Armenia, Mosul, and the Caliphate as they relate to the history of Ottoman and Turkish foreign policy are considered foundational resources. -

Marketing Plan

ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP An Allied Artists Int'l Company MARKETING & PROMOTION MARKETING PLAN: ROCKY KRAMER "FIRESTORM" Global Release Germany & Rest of Europe Digital: 3/5/2019 / Street 3/5/2019 North America & Rest of World Digital: 3/19/2019 / Street 3/19/2019 MASTER PROJECT AND MARKETING STRATEGY 1. PROJECT GOAL(S): The main goal is to establish "Firestorm" as an international release and to likewise establish Rocky Kramer's reputation in the USA and throughout the World as a force to be reckoned with in multiple genres, e.g. Heavy Metal, Rock 'n' Roll, Progressive Rock & Neo-Classical Metal, in particular. Servicing and exposure to this product should be geared toward social media, all major radio stations, college radio, university campuses, American and International music cable networks, big box retailers, etc. A Germany based advance release strategy is being employed to establish the Rocky Kramer name and bona fides within the "metal" market, prior to full international release.1 2. OBJECTIVES: Allied Artists Music Group ("AAMG"), in association with Rocky Kramer, will collaborate in an innovative and versatile marketing campaign introducing Rocky and The Rocky Kramer Band (Rocky, Alejandro Mercado, Michael Dwyer & 1 Rocky will begin the European promotional campaign / tour on March 5, 2019 with public appearances, interviews & live performances in Germany, branching out to the rest of Europe, before returning to the U.S. to kick off the global release on March 19, 2019. ALLIED ARTISTS INTERNATIONAL, INC. ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP 655 N. Central Ave 17th Floor Glendale California 91203 455 Park Ave 9th Floor New York New York 10022 L.A. -

Desátý Magazín Paláce Akropolis 09–12 2010 Obsah

Desátý Magazín Paláce Akropolis 09–12 2010 Obsah Téma Daniel Řehák Studentský film 04 Divadlo Tomáš Vostrý Imre Thormann znovu v Paláci Akropolis 17 Hudba Jan Pomuk Štěpánek A Naifa: Nový rozměr melancholie 22 Hudba Jiří Hradecký O démonovi, který si chtěl zahrát v kabaretu 24 Hudba Ondřej Stratilík Norsko útočí Znovu a jinak 26 Hudba Petr Dorůžka Sophie se vrací jako superstar 28 Hudba Karel Veselý K hudbě si sám vymýšlím příběhy 30 Hudba Petr Dorůžka Punkrock, Balkán i poezie z gulagu 32 Hudba Petr Dorůžka I pianisté prodávají pizzu 34 Hudba Šimon Kotek Pramen řeky znovuzrození 38 Hudba Ondřej Bezr Velký návrat The Holmes Brothers 40 Hudba Ondřej Kopička The Best of Future Line míří do Vystřelenýho voka 42 Hudba Ondřej Kopička a Šimon Kotek Vladimír Mišík a jeho Ztracený podzim 44 Výstava Richard Vodička Pohledy Vladimíra Kovaříka 46 Střípky 49 Resumé 56 Fotogalerie Dimír Šťastný 58 MaPA_OBSAH VÁžENÍ čTENÁřI, Léto nám pomalu končí. Slunce jsme si užili sice zahraje v pražském Rudolfinu spolu s Pražským ko- dost, ale svorně doufáme, že vydrží až do podzim- morním orchestrem. O jejich spolupráci se dočtete ních měsíců. Kromě krásného počasí, koupačky, do- v našem exkluzivním rozhovoru. volených a spálených zad je léto také časem festiva- Do Akropole se také vrací úspěšná Sophie Hunger se lů, a to nejen hudebních. zbrusu novým albem. Letos poprvé hostí Palác Akropolis prestižní filmový Do třetice velkých návratů nás čeká velký comeback festival studentských a nezávislých filmů Fresh Film české legendy jménem Vltava, která si dala deseti- Fest. Takovou událost nesmíme nechat bez povšim- letou přestávku. -

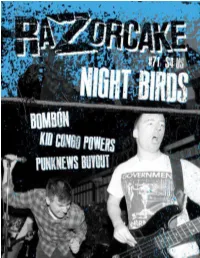

Razorcake Issue

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Curious about how to realistically help Razorcake? If you wish to donate through the mail, please rip this page out and send it to: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. PO Box 42129 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Just NAME: turn ADDRESS: the EMAIL: page. DONATION AMOUNT: 5D]RUFDNH*RUVN\3UHVV,QFD&DOLIRUQLDQRWIRUSUR¿WFRUSRUDWLRQLVUHJLVWHUHG DVDFKDULWDEOHRUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKWKH6WDWHRI&DOLIRUQLD¶V6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWHDQGKDV EHHQJUDQWHGRI¿FLDOWD[H[HPSWVWDWXV VHFWLRQ F RIWKH,QWHUQDO5HYHQXH &RGH IURPWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV,562XUWD[,'QXPEHULV <RXUJLIWLVWD[GHGXFWLEOHWRWKHIXOOH[WHQWSURYLGHGE\ODZ SUBSCRIBE AND HELP KEEP RAZORCAKE IN BUSINESS Subscription rates for a one year, six-issue subscription: U.S. – bulk: $16.50 • U.S. – 1st class, in envelope: $22.50 Prisoners: $22.50 • Canada: $25.00 • Mexico: $33.00 Anywhere else: $50.00 (U.S. funds: checks, cash, or money order) We Do Our Part www.razorcake.org Name Email Address City State Zip U.S. subscribers (sorry world, int’l postage sucks) will receive either Grabass Charlestons, Dale and the Careeners CD (No Idea) or the Awesome Fest 666 Compilation (courtesy of Awesome Fest). Although it never hurts to circle one, we can’t promise what you’ll get. Return this with your payment to: Razorcake, PO Box 42129, LA, CA 90042 If you want your subscription to start with an issue other than #72, please indicate what number. TEN NEW REASONS TO DONATE TO RAZORCAKE VPDQ\RI\RXSUREDEO\DOUHDG\NQRZRazorcake ALVDERQDILGHQRQSURILWPXVLFPDJD]LQHGHGLFDWHG WRVXSSRUWLQJLQGHSHQGHQWPXVLFFXOWXUH$OOGRQDWLRQV The Donation Incentives are… -

MOTHER NATURE SMILES on KSW!!!!

Make Your Plans for the Founder’s Day Cornroast and Family Picnic, on August 25th!!! ISSUE 16 / SUMMER ’12 Bill Parsons, Editor 6504 Shadewater Drive Hilliard, OH 43026 513-476-1112 [email protected] THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CALEDONIAN SOCIETY OF CINCINNATI In This Issue: Nature Smiles on KSW 1 MOTHER NATURE SMILES on KSW!!!! Cornroast Aug 25th 2 *Schedule of Events 2 ust in case you did not attend the 30th Annual Kentucky Scottish Scotch Ice Cream? 3 JWeekend on the 12th of May, here CSHD 3 is what you missed. First off, a perfectly Cinti Highld Dancers 3 grand sunny day (our largest crowd Nessie Banned in WI 4 over the last three years); secondly, *Resource List 4 the athletics, Scottish country dancing, highland dancing, clogging, Seven Assessment KSW? 5 Nations, Mother Grove, the Border Scottish Unicorns 5 Collies, British Cars, Clans, and Pipe Glasgow Boys ’n Girls 6-11 Bands. This year we had a new group *Email PDF Issue only* called “Pictus” perform and we added a welly toss for the children. Colours Glasgow Girls 8* were posted by the Losantiville Scots on FIlm-BRAVE 12* Highlanders. Out of the Sporran 13* Food and drink. For the first time, the Park served beer and wine in the “Ole Scottish Pub”. Food vendors PAY YOUR DUES! included barbecue, meat pies, fish and Don’t forget to pay your current chips, gourmet ice cream, and bakery dues. You will not be able to vote goods galore. at the AGM unless your dues are Twelve vendors. From kilts to current. -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

A Sweet Lullaby for World Music

A Sweet Lullaby for World Music Steven Feld T o begin, the music globalization commonplaces that are most broadly circu- lating in Western intellectual discourse as actualities or immediate predic- tions at the end of the twentieth century: 1. Music’s deep connection to social identities has been distinctively intensified by globalization. This intensification is due to the ways cultural separation and social exchange are mutually accelerated by transnational flows of technology, media, and popular culture. The result is that musical identities and styles are more visibly transient, more audibly in states of constant fission and fusion than ever before. 2. Our era is increasingly dominated by fantasies and realizations of sonic virtuality. Not only does contemporary technology make all musical worlds actually or potentially transportable and hearable in all others, but this transportability is something fewer and fewer people take in any way to be remarkable. As sonic virtuality is increasingly naturalized, everyone’s musical world will be felt and experienced as both more definite and more vague, specific yet blurred, particular but general, in place and in motion. 3. It has taken only one hundred years for sound recording technologies to amplify sonic exchange to a point that overwhelms prior and contiguous his- Thanks to Afunakwa, Deep Forest, and Jan Garbarek for the unending mix of celebration and anxiety in their recordings of Rorogwela; to Marit Lie, Odd Are Berkaak, and Hugo Zemp for their friendship, comments, and provision of documents; to Arjun Appadurai, Veit Erlmann, Lisa Hender- son, Alison Leitch, David Samuels, Tim Taylor, and Public Culture’s readers for suggestions; and to Spring 1999 colloquia audiences at Mt.