Visitors' Emotional Expression in Urban Forest Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Book(EN)

TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA 2025: CONNECTING THE WORLD 中国交通 2025:联通世界 Transportation in China 2025: Connecting the World 1 CONTENTS The 19th COTA International Conference of Transportation Professionals Transportation in China 2025: Connecting the World Welcome Remarks ······································ 4 Organization Council ································· 8 Organizers ······················································ 13 Sponsors ·························································· 17 Instructions for Presenters ························ 19 Instructions for Session Chairs ················ 19 Program at a Glance ··································· 20 Program ··························································· 22 Poster Sessions ············································· 56 General Information ··································· 86 Conference Speakers & Organizers ······· 95 Pre- and Post-CICTP2019 Events ············ 196 • Welcome Remarks It is our great pleasure to welcome you all to the 19th COTA International Conference Welcome of Transportation Professionals (CICTP 2019) in Nanjing, China. The CICTP2019 is jointly Remarks organized by Chinese Overseas Transportation Association (COTA), Southeast University, and Jiaotong International Cooperation Service Center of Ministry of Transport. The CICTP annual conference series was established by COTA back in 2001 and in the past two decades benefited from support from the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Transportation Research Board (TRB), and many other -

Annex I: Introduction to the Designing Task – North Area of Harbin Railway Station

Annex I: Introduction to the designing task – North area of Harbin Railway Station Background 1. Harbin City Harbin is an important city in the north of the Northeast China and also one of the 10 largest cities in China. The city is the political, economic, cultural, financial and scientific and technological centre and the hub of communications of Heilongjiang Province, where the Harbin-Dalian Railway, Harbin-Manchuria Railway, Harbin-Suifenhe Railway, Harbin-Bei’an Railway and Harbin-Lafa Railway converge. Harbin is a young city that has grown up together with the development of railways. In the past years, the construction of railways contributed greatly to the development of the city; nowadays, the reconstruction and upgrading of the existing Harbin Railway Station also bears on the development of the city and on the life of every Harbin citizen in the future. Harbin is a well-known international tourist destination. The CR Expo which is reputed in the Northeast Asia, and the world-renowned Ice and Snow Festival, as well as international beer festivals and auto shows are held here every year. In addition, the city once successfully hosted the 2009 World Winter Universiade. Harbin is a city of art and culture. It is the seat of the renowned Harbin Summer Music Concert, the Central Avenue, the St. Sophia Church and the Jihong Bridge (Rainbow Bridge), etc. It is also the cradle of the long-standing Jurchen, Liao and Jin ethnic culture. In history, the cultures of the Central Plains, the Liao and Jin peoples and the whole world integrated here and created the Unique Harbin Culture, which finds expression in the everyday life of Harbin citizens. -

C P G P S Forum 2 0

C P G P S Forum 2 0 1 7 CPGPS 2017 Forum on Cooperative Positioning and Service Agenda Harbin, China May 19-21, 2017 1 General Information Organizing Committee General Chair Xiaolin Meng University of Nottingham, UK General Co-Chair Wei Gao Harbin Institute of Technology, China Chuang Shi Wuhan University, China Shuanggen Jin Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, China Jian Wang China University of Mining & Technology, China Xiaohong Zhang Wuhan University, China Organizing Chair Fei Yu Harbin Institute of Technology, China Members of Technical Program Committees Wu Chen Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China Ruizhi Chen Wuhan University, China Kai-Wei Chiang National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan Danan Dong East China Normal University, China Mingyi Du Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, China Peng Fang UCSD, USA Yanming Feng Queensland University of Technology, Australia Yang Gao University of Calgary, Canada Wei Gao Harbin Institute of Technology, China Linlin Ge University of New South Wales, Australia Maorong Ge GeoForschungsZentrum (GFZ), Germany 2 Shuanggen Jin Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, China Bofeng Li Tongji University, China Zhizhao Liu Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China Xiaoji Niu Wuhan University, China Jinling Wang University of New South Wales, Australia Linyuan Xia Sun Yat-Sen University, China Aigong Xu Liaoning Technical University, China Guochang Xu Shangdong University, China Hongping Zhang Wuhan University, China Kefei Zhang RMIT University, Australia Qin Zhang Chang-An University, -

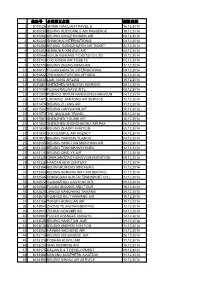

航协号 公司英文名称 到帐日期 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

航协号 公司英文名称 到帐日期 1 8010026 SHISHI QIAOLIAN TRAVEL & 16.12.2014 2 8010030 BEIJING XUEYUANLU AIR PASSENGE 18.12.2014 3 8010262 BEIJING XINGZHONGBIN AIR 08.12.2014 4 8010424 SHANGHAI INTERNATIONAL 04.12.2014 5 8010483 BEIJING GONGZHUFEN AIR TICKET 22.12.2014 6 8010494 SHANGHAI XIN GUO AIR 04.12.2014 7 8010564 GUILIN GUIKANG TICKETS CO LTD 10.12.2014 8 8010704 CIXI XUNDA AIR TICKETS 03.12.2014 9 8010774 BEIJING ZHENG XIANG AIR 17.12.2014 10 8010811 FUJIAN KANGTAI INTERNATIONAL 08.12.2014 11 8010822 ZHEJIANG FOREIGN AFFAIRS 10.12.2014 12 8010833 LIAN JIANG AIRLINE 19.12.2014 13 8010881 SHENZHEN WANGYUN KUNMING 26.12.2014 14 8011006 FUJIAN RAILWAYS INT'L 08.12.2014 15 8011290 FUZHOU JINYUN HANGKONG HANGYUN 04.12.2014 16 8011441 LIAONING JIANTONG AIR SERVICE 12.12.2014 17 8011474 BEIJING ZI LANG AIR 11.12.2014 18 8011544 BEIJING LANYUXING AIR 12.12.2014 19 8011570 THE QIAOLIAN TRAVEL 08.12.2014 20 8011581 SHENZHEN YOUSHI AIR 18.12.2014 21 8011802 SHENZHEN ZHONGHAOHUI AIR PAX 08.12.2014 22 8011824 BEIJING ZHAORI AVIATION 05.12.2014 23 8011850 SUCCESSFUL AIR AGENCY 05.12.2014 24 8011872 BEIJING TIAHONG YUANDU 04.12.2014 25 8012045 BEIJING HANGTIAN MIANYUAN AIR 23.12.2014 26 8012104 BEIJING TONGSHANGYUNDA 12.12.2014 27 8012115 BEIJING QING YE AIR 17.12.2014 28 8012325 QINHUANGDAO HONGYUAN KONGYUN 09.12.2014 29 8012336 HANDAN NEW CENTURY 11.12.2014 30 8012384 BEIJINGRUIFENG XINCHENG 11.12.2014 31 8012443 BEIJING GENERALWAY AIR SERVICE 17.12.2014 32 8012546 DONGGUAN GUOTAI TRANSPORT CO.L 23.12.2014 33 8012572 GUANGZHOU JIAOYIHUI INTL 09.12.2014 34 -

The Hailar Incident: the Nadir of Troubled Relations Between the Czechoslovak Legionnaires and the Japanese Army, April 1920

Acta Slavica Iaponica, Tomus 29, pp. 103‒122 The Hailar Incident: The Nadir of Troubled Relations between the Czechoslovak Legionnaires and the Japanese Army, April 1920 Martin Hošek INTRODUCTION The Czechoslovak Legion in Russia were employed in the Allied inter- vention from 1918 to 1920 on the side of the anti-Bolshevik regime of Admiral Kolchak, who in turn was supported by the Allies. This military service was very unpopular among the legionnaires who were impatient to return home. Nevertheless, they accepted the necessity of their engagement as a powerful argument for the victorious world powers to recognize Czechoslovakia as an independent state after the First World War. By the end of 1919, the Kolchak regime had fallen under the Red Army offensive and suffered the outbreak of many uprisings in the hinterland. This marked the end of Allied intervention, and all surviving forces, including the Czechoslovak Legion, started evacuating from Siberia. However, to make it to the ships at Vladivostok, the legionnaires were now ready to fight anybody, friend or foe, who stood in their way. In April 1920, although most Czechoslovak regiments had reached Vladivostok, the last echelons of their rearguard had just entered the Chinese Eastern Railway (C. E. R.), which connected the Trans-Baikal region with the Russian Far East via the territory of northeast China. Despite many difficulties, the Czechoslovak leadership was confident that the evacuation would be com- pleted successfully. However, this last phase did not go smoothly because of worsening relations between the legionnaires and the Japanese Imperial Army. Another reason was the generally tense situation along the C. -

Harbin Overview 01

Harbin Overview 01 Harbin Quick Facts Contents City Name:Harbin (哈尔滨) 01 Harbin Quick Facts Population:9.94 million (2010) 01 Overview Location:Northeast China Features: It is famous for the breathtaking 02 Harbin Weather scenery of sonw. 03-12 What to Do in Harbin Area Code:0451 13-14 How to Travel in Harbin Zip Code: 150000 15-16 What to Eat in Harbin 17-19 What to Buy in Harbin Overview 20-22 Harbin Hotels Geographical Location 23-25 Harbin Restaurant The city of Harbin is the capital of 26-27 Harbin Transportation Heilongjiang Province, China's most northerly province. Harbin is situated near the northern extremity of the Northeast China Plain, the large plain that lies above the Bay of Bohai. And Harbin is the political, economic, cultural and technological center of Heilongjiang Province, as well as the province's transportation and communication hub. History Harbin, situated on the Songhua River, is the site of the prehistoric (BCE 2200, roughly, or the late Stone Age), pre-Xia (BCE 2000-1500) Dynasty settlement referred to as Pokai. The first Chinese village here would be known as Pinkiang, before the village was eventually occupied by nomadic Turkic tribes that migrated into the area later known as Manchuria from the area that would be known as Siberia. Harbin Weather 02 Climatic Features Harbin belongs to temperate continental monsoon climate, with four distinct seasons and large annual range of temperature. It boasts long and chilly winters and short and comparatively warm summers, with the annual average temperature of 3.6℃. The temperature in spring and autumn changes greatly. -

Modernization and the Sedimentation of Cultural Space of Harbin: the Stratification of Material Culture

Intercultural Communication Studies XVII: 1 2008 Song, St. Clair, & Wang Modernization and the Sedimentation of Cultural Space of Harbin: The Stratification of Material Culture Wei Song & Robert N. St. Clair Song Wang University of Louisville Harbin Institute of Technology Not all cities are modernized in the same way. There are different forces from the past that interact with the processes of modernization to create very different cultural spaces. For example, in China the modern city of Harbin has undergone similar processes of modernization as other cities in the country. However, Harbin remains a culturally different entity and these differences can be attributed to the differences in their cultural past. This is because the cultural present is embedded in the cultural past and the present forces of modernization must not only be embedded in the cultural spaces of the past but it must also be integrated into its archeological strata. Hence, in order to explain this phenomenon, a different model of cultural space is needed. Such a model has been proposed. The sedimentation theory of cultural space is such a model (St. Clair, 2007). It is based on the metaphor of the “Archeology of Knowledge” in which Foucault (1969) envisions knowledge as layers of human activity deposited in a cultural space over time. A modification and expansion of this metaphor can be found in the sedimentation theory of cultural space, which not only envisions time as the accumulation of social practices layered in cultural space, but also provides epistemological mechanisms that explain how reality is socially reconstructed within a cultural space. -

Cultural Interaction and Confrontation Among the Haunting Ghosts of Russians, Japanese, and Chinese in Harbin

THE POLITICS OF MEMORY: CULTURAL INTERACTION AND CONFRONTATION AMONG THE HAUNTING GHOSTS OF RUSSIANS, JAPANESE, AND CHINESE IN HARBIN JING XU A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HUMANITIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2019 © Jing Xu, 2019 Abstract This dissertation focuses on a spatial analysis of the cultural memories of Harbin, a city in Northeast China, a former (semi)colony of Russia and Japan, and a habitat of more than forty nationalities from across the world in the first half of the twentieth century. Harbin’s history, determined in great part by a large foreign presence, is still a matter of contention in China and elsewhere. By adopting Pierre Nora’s concept of “lieux de mémoire (places of memory),” Henri Lefebvre’s notion of “the social production of space,” and concepts and theories of many others, this dissertation investigates the contested memories of Harbin through the lens of architecture, literature, film, and television drama. It conducts interdisciplinary and inter-medial examinations of Harbin as an encompassing lieu de mémoire, where various practices demonstrate, individually and collectively, differently yet consistently, the social signification of the city’s pasts in the present, enriching the city with ambivalent and contradictory meanings, and contributing to the social production of the memorial space and spatial memory of the city. This dissertation examines Harbin as a contact zone amongst Russia, Japan, and China, and as a periphery of the cultural heartland of China. It attaches importance to memories as an arena for the contemporary Harbiners to negotiate the divergent ideologies, power contests, and economic and cultural concerns. -

Network Characteristics and Vulnerability Analysis of Chinese Railway Network Under Earthquake Disasters

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Network Characteristics and Vulnerability Analysis of Chinese Railway Network under Earthquake Disasters Lingzhi Yin 1 and Yafei Wang 2,* 1 School of Information Science and Technology, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou 310018, China; [email protected] 2 Key Laboratory of Regional Sustainable Development Modeling, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 23 November 2020; Published: 25 November 2020 Abstract: The internal structure and operation rules of railway network have become increasingly complex along with the expansion of the network, putting a higher demand on the development of the railway and the reliability and adaptability of the railway under earthquake disasters. The theory and method concerning complex railway network can well capture the internal structure of railway facilities system and the relationship between subsystems. However, most of the research focuses on the vulnerability based on the logical network of railway, deviating from the actual spatial location of railway network. Additionally, only random attacks and deliberate attacks are factored in, ignoring the impact of earthquake disasters on actual railway lines. Therefore, this paper built a geographic railway network and analyzed topological structure of the network and its vulnerability under earthquake disasters. First, the geographic network of Chinese railway was built based on the methods of complex network, linear reference and dynamic segmentation. Second, the spatial distribution of railway network flow was analyzed by node degree, betweenness and clustering coefficient. Finally, the vulnerability of the geographic railway network in areas with high seismic hazards were assessed, aiming to improve the capacity to prevent and resist earthquake disasters. -

World Bank Document

E4331 V2 REV Certificate No.: GHPZ Class A No.1703 Project No.: HKYBGS—(2013) 008 Public Disclosure Authorized Harbin Alpine-cold Intelligent Public Traffic System Construction Project Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Report (Pre-evaluation Version) Public Disclosure Authorized Entrusted by: Communications Bureau of Harbin Prepared by: Environmental Protection Science Research Public Disclosure Authorized Institute of Heilongjiang Province November 2013 Environmental Impact Report of Harbin Alpine-cold Intelligent Public Traffic System Construction Project Project name: Harbin Alpine-cold Intelligent Public Traffic System Construction Project Text type: Project No.: HKYBGS—(2013) 008 Entrusted by: Communications Bureau of Harbin Prepared by: Environmental Protection Science Research Institute of Heilongjiang Province Legal representative: Chi Xiaode Evaluation certificate: GHPZ Class A No.1703 Project leader: Sun Baini A17030081000 He Chenyan A17030009 Technical reviewer: Guan Kezhi A17030023 Main Preparation Personnel Preparation Registration/Wor Duty Title Signature Personnel k License No. Report Sun Baini Senior engineer A17030081000 preparation Report Assistant Qin Bo preparation engineer Report Assistant Jiang Yueli A17030047 preparation engineer II Environmental Impact Report of Harbin Alpine-cold Intelligent Public Traffic System Construction Project Foreword Since the development of urbanization and mechanization has led to the ever-increasing gasoline usage in China, energy will be principal factor influencing -

Session Overview

Session Overview Friday, December 18, 2015 09:00-18:00 Registration Lobby of HanlinTianyue Hotel Saturday, December 19, 2015 08:30-09:00 Opening Ceremony Plenary Speech I Dr. Wei-Shinn (Jeff) Ku 09:00-09:40 Session Chair: Jinbao Li Hanlin Tianyue 09:40-09:50 Group photo Hotel 09:50-10:10 Coffee break Sunshine Hall Plenary Speech II Dr. Qing Yang {11th floor} 10:10-10:50 Session Chair: Yan Yang Plenary Speech III Dr. Yanmin Zhu 10:50-11:30 Session Chair: Longjiang Guo 11:30-12:30 Lunch-Hanlin Tianyue Hotel Cafeteria{2nd floor} Meeting Room 1, Meeting Room 2 13:30-15:00 Sessions and VIP Room {10th floor} 15:00-15:30 Coffee break {10th floor} Meeting Room 1, Meeting Room 2 15:30-17:00 Sessions and VIP Room {10th floor} 17:00-18:30 Dinner-Hanlin Tianyue Hotel Cafeteria{2nd floor} Sunday, December 20, 2015 Meeting Room 1, Meeting Room 2 08:30-10:00 Sessions and VIP Room {10th floor} 10:00-10:30 Coffee break {10th floor} Meeting Room 1, Meeting Room 2 10:30-12:00 Sessions and VIP Room {10th floor} 12:00-13:00 Lunch-Hanlin Tianyue Hotel Cafeteria{2nd floor} Get together in the lobby of Hanlin Tianyue Hotel 13:00 Tour in Harbin City and eat dinner out Meeting Room 1, Meeting Room 2 and VIP Room are both on the 10th floor. 1 2 Preface Dear distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen: On the opening of 2015 4th International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology (ICCSNT 2015), I would like to extend my warm welcome and deep gratitude to all of you here. -

Harbin Introduction

Harbin Introduction I. Overview Harbin is the capital and largest city of Heilongjiang province in the northeastern region of the People's Republic of China. Holding sub-provincial administrative status, Harbin has direct jurisdiction over nine metropolitan districts, two county-level cities and seven counties. Harbin is the eighth most populous Chinese city and the most populous city in Northeast China. According to the 2010 census, the built-up area made of seven out of nine urban districts (all but Shuangcheng and Acheng not urbanized yet) had 5,282,093 inhabitants, while the total population of the sub-provincial city was up to 10,635,971. Harbin serves as a key political, economic, scientific, cultural, and communications hub in Northeast China, as well as an important industrial base of the nation. Harbin, which was originally a Manchu word meaning "a place for drying fishing nets", grew from a small rural settlement on the Songhua River to become one of the largest cities in Northeast China. Founded in 1898 with the coming of the Chinese Eastern Railway, the city first prospered as a region inhabited by an overwhelming majority of the immigrants from the Russian Empire. Having the most bitterly cold winters among major Chinese cities, Harbin is heralded as the Ice City for its well-known winter tourism and recreations. Harbin is notable for its beautiful ice sculpture festival in the winter. Besides being well known for its historical Russian legacy, the city serves as an important gateway in Sino-Russian trade today, containing a sizable population of Russian diaspora.