The Fisheries Resources of Clipperton Island (France)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Citizenship Active Exchange Visitors in 2017

Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 Active Exchange Visitors Country of Citizenship in 2017 AFGHANISTAN 418 ALBANIA 460 ALGERIA 316 ANDORRA 16 ANGOLA 70 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 29 ARGENTINA 8,428 ARMENIA 325 ARUBA 1 ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS 1 AUSTRALIA 7,133 AUSTRIA 3,278 AZERBAIJAN 434 BAHAMAS, THE 87 BAHRAIN 135 BANGLADESH 514 BARBADOS 58 BASSAS DA INDIA 1 BELARUS 776 BELGIUM 1,938 BELIZE 55 BENIN 61 BERMUDA 14 BHUTAN 63 BOLIVIA 535 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 728 BOTSWANA 158 BRAZIL 19,231 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 3 BRUNEI 44 BULGARIA 4,996 BURKINA FASO 79 BURMA 348 BURUNDI 32 CAMBODIA 258 CAMEROON 263 CANADA 9,638 CAPE VERDE 16 CAYMAN ISLANDS 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 27 CHAD 32 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 CHILE 3,284 CHINA 70,240 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 2 CLIPPERTON ISLAND 1 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS 3 COLOMBIA 9,749 COMOROS 7 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 37 CONGO (KINSHASA) 95 COSTA RICA 1,424 COTE D'IVOIRE 142 CROATIA 1,119 CUBA 140 CYPRUS 175 CZECH REPUBLIC 4,048 DENMARK 3,707 DJIBOUTI 28 DOMINICA 23 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 4,170 ECUADOR 2,803 EGYPT 2,593 EL SALVADOR 463 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 9 ERITREA 10 ESTONIA 601 ETHIOPIA 395 FIJI 88 FINLAND 1,814 FRANCE 21,242 FRENCH GUIANA 1 FRENCH POLYNESIA 25 GABON 19 GAMBIA, THE 32 GAZA STRIP 104 GEORGIA 555 GERMANY 32,636 GHANA 686 GIBRALTAR 25 GREECE 1,295 GREENLAND 1 GRENADA 60 GUATEMALA 361 GUINEA 40 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 GUINEA‐BISSAU -

Répartition De La Population En Polynésie Française En 2017

Répartition de la population en Polynésie française en 2017 PIRAE ARUE Paopao Teavaro Hatiheu PAPEETE Papetoai A r c h MAHINA i p e l d FAA'A HITIAA O TE RA e s NUKU HIVA M a UA HUKA r q PUNAAUIA u HIVA OA i TAIARAPU-EST UA POU s Taiohae Taipivai e PAEA TA HUATA s NUKU HIVA Haapiti Afareaitu FATU HIVA Atuona PAPARA TEVA I UTA MOO REA TAIARAPU-OUEST A r c h i p e l d Puamau TAHITI e s T MANIHI u a HIVA OA Hipu RA NGIROA m Iripau TA KAROA PUKA P UKA o NA PUKA Hakahau Faaaha t u Tapuamu d e l a S o c i é MAKEMO FANGATA U - p e l t é h i BORA BORA G c a Haamene r MAUPITI Ruutia A TA HA A ARUTUA m HUAHINE FAKARAVA b TATAKOTO i Niua Vaitoare RAIATEA e TAHITI r TAHAA ANAA RE AO Hakamaii MOORE A - HIK UE RU Fare Maeva MAIAO UA POU Faie HA O NUKUTAVAKE Fitii Apataki Tefarerii Maroe TUREIA Haapu Parea RIMATARA RURUTU A r c h Arutua HUAHINE i p e TUBUAI l d e s GAMBIE R Faanui Anau RA IVAVAE A u s Kaukura t r Nombre a l AR UTUA d'individus e s Taahuaia Moerai Mataura Nunue 20 000 Mataiva RA PA BOR A B OR A 10 000 Avera Tikehau 7 000 Rangiroa Hauti 3 500 Mahu Makatea 1 000 RURUT U TUBUAI RANGIROA ´ 0 110 Km So u r c e : Re c en se m en t d e la p o p u la ti o n 2 0 1 7 - IS P F -I N SE E Répartition de la population aux Îles Du Vent en 2017 TAHITI MAHINA Paopao Papetoai ARUE PAPEETE PIRAE HITIAA O TE RA FAAA Teavaro Tiarei Mahaena Haapiti PUNAAUIA Afareaitu Hitiaa Papenoo MOOREA 0 2 Km Faaone PAEA Papeari TAIARAPU-EST Mataiea Afaahiti Pueu Toahotu Nombre PAPARA d'individus TEVA I UTA Tautira 20 000 Vairao 15 000 13 000 Teahupoo 10 000 TAIARAPU-OUEST -

The Effects of the Cyclones of 1983 on the Atolls of the Tuamotu Archipelago (French Polynesia)

THE EFFECTS OF THE CYCLONES OF 1983 ON THE ATOLLS OF THE TUAMOTU ARCHIPELAGO (FRENCH POLYNESIA) J. F. DUPON ORSTOM (French Institute ofScientific Research for Development through cooperation), 213 Rue Lafayette - 75480 Paris Cedex 10, France Abstract. In the TUAMOTU Archipelago, tropical cyclones may contribute to the destruction as well as to some building up of the atolls. The initial occupation by the Polynesians has not increased the vulnerability of these islands as much as have various recent alterations caused by European influence and the low frequency of the cyclone hazard itself. An unusual series of five cyclones, probably related to the general thermic imbalance of the Pacific Ocean between the tropics struck the group in 1983 and demonstrated this vulnerability through the damage that they caused to the environment and to the plantations and settle ments. However, the natural rehabilitation has been faster than expected and the cyclones had a beneficial result in making obvious the need to reinforce prevention measures and the protection of human settle ments. An appraisal of how the lack of prevention measures worsened the damage is first attempted, then the rehabilitation and the various steps taken to forestall such damage are described. I. About Atolls and Cyclones: Some General Information Among the islands of the intertropical area of the Pacific Ocean, most of the low-lying lands are atolls. The greatest number of them are found in this part of the world. Most atolls are characterized by a circular string of narrow islets rising only 3 to 10 m above the average ocean level. -

Publications

Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation Volume 8 Article 13 Issue 4 Rapa Nui Journal 8#4, December 1994 1994 Publications Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj Part of the History of the Pacific slI ands Commons, and the Pacific slI ands Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (1994) "Publications," Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation: Vol. 8 : Iss. 4 , Article 13. Available at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj/vol8/iss4/13 This Commentary or Dialogue is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation by an authorized editor of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Publications LETTERS TO THE EDITOR PUBLICATIONS ~After completing my paper on Austronesian Transport -Anderson, Atholl; Helen Leach; Ian Smith; and Richard Walter. 1994. Reconsideration of the Marquesan sequence in (RNJ 8,3 :67-70), a book was brought to my attention by Tricia East Polynesia prehistory with particular reference to Hane AJlen at the Rapa Nui Rendezvous in Laramie, Wyoming. It (MUH 1). Archaeology in Oceania 29(1):29-52. concerns an item in Peter Buck's book Arts and Crafts of Hawaii (Bishop Museum Special Publication 45, 1957). In it, -Becker, Nancy. 1994. Easter Island: The Archaeological holua, the Hawaiian equivalent to the Rapa Nui hakape'i, is Legacy of Rapa Nui. Site Saver: The Newsletter ofSacred described. In Hawai'i, sliding down a hill was not done on Sites International Foundation. -

Invasion of French Polynesia by Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Releases of Two Natural Enemies: a 17-Year Case Study

BPactroceraroceedings dorsalis of the h controlawaiian einntomological French Polynesia society (2013) 45:31–43 31 From Eradication to Containment: Invasion of French Polynesia by Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Releases of Two Natural Enemies: A 17-Year Case Study Luc Leblanc1, Roger I. Vargas2*, and Rudolph Putoa3 1Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Science, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA. 2*USDA-ARS, U.S. Pacific Basin Agricultural Research Center, 64 Nowelo St, Hilo, HI 96720, USA. 3Service du Développement Rural, Département de la Protection des Végétaux, B.P. 100, Papeete, Tahiti, 98713, French Polynesia. *Corresponding author: [email protected], tel (+1)808-959-4329, fax (+1)808-959-5470. Abstract. Four economic species of Bactrocera flies have sequentially invaded French Polynesia: B. kirki (Froggatt) in 1928, B. tryoni (Froggatt) in 1970, B. dorsalis (Hendel), detected on Tahiti in 1996, and B. xanthodes (Broun), detected on the Austral Islands in 1998. Following a failed attempt to eradicate B. dorsalis, documented in this paper, it became established and the dominant fruit fly, displac- ing B. kirki and B. tryoni. Two braconid parasitoids were introduced from Hawaii and established: Fopius arisanus (Sonan) (released in 2002) and Diachasmimorpha longicaudata (Ashmead) (released in 2007). By 2009 mean parasitism for fruit flies infesting common guava (Psidium guajava), Tahitian chestnut (Inocarpus fagifer), and tropical almond (Terminalia catappa) fruits on Tahiti was 70%, and 95% of the emerged parasitoids were F. arisanus. Numbers of B. dorsalis trapped from methyl eugenol and bred from guava, Tahitian chestnut and tropical almond have been reduced by 87%, 89%, 88%, and 91–94%, respectively, from the 2002–03 peaks. -

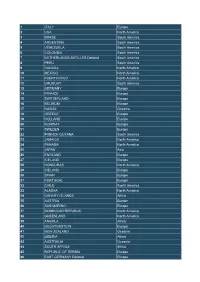

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania Prepared for the US Department of Defense’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance May 2020 Written by: Jonah Bhide Grace Frazor Charlotte Gorman Claire Huitt Christopher Zimmer Under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Busby 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 United States 8 Oceania 22 China 30 Australia 41 New Zealand 48 France 53 Japan 61 Policy Recommendations for US Government 66 3 Executive Summary Research Question The current strategic landscape in Oceania comprises a variety of complex and cross-cutting themes. The most salient of which is climate change and its impact on multilateral political networks, the security and resilience of governments, sustainable development, and geopolitical competition. These challenges pose both opportunities and threats to each regionally-invested government, including the United States — a power present in the region since the Second World War. This report sets out to answer the following questions: what are the current state of international affairs, complexities, risks, and potential opportunities regarding climate security issues and geostrategic competition in Oceania? And, what policy recommendations and approaches should the US government explore to improve its regional standing and secure its national interests? The report serves as a primer to explain and analyze the region’s state of affairs, and to discuss possible ways forward for the US government. Given that we conducted research from August 2019 through May 2020, the global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus added additional challenges like cancelling fieldwork travel. However, the pandemic has factored into some of the analysis in this report to offer a first look at what new opportunities and perils the United States will face in this space. -

TAHITI.2016 the Best of the TUOMOTU Archipelago MAY 15-25, 2016

TAHITI.2016 The Best of the TUOMOTU Archipelago MAY 15-25, 2016 If you have thought of warm crystalline South Pacific Ocean, little sand islets with coconut palms swaying down to the waterline and water to blue it appears electric? Very few of us are immune to this sirens call of French Polynesia’s image – real or imagined - and so these celebrated gems of the South Pacific have become a crossroads for dreamers, adventurers and escapist sharing a common wanderlust. We count ourselves among these folk… following in the wake of Magellan, Cook and Wallis, but by means easier than they could have ever imagined. As a diver, there is also something special beneath the azure surface that beckons, something never painted by Gauguin. In fact, the far-flung waters around French Polynesia are some of the SHARK-iest in the world… and the high voltage diving serves up the kind excitement not every paradise can deliver. The expedition is scheduled for MAY 15-25, a 10 day itinerary starting in the famed atoll of Rangiroa and weather permitting include Tikehau, Apataki, Toau and will end the journey in the stunning atoll of Fakarava. We may also get a chance to stop at a couple of others along the way. The diving is off tenders that transport us to the sites where strong currents can be present. The thrill is not only to witness what gets drawn to these spots but also to ride the crystalline currents without fighting them. Advanced diver and Nitrox certification required to join this trip. -

ISO Country Codes

COUNTRY SHORT NAME DESCRIPTION CODE AD Andorra Principality of Andorra AE United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates AF Afghanistan The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan AG Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda (includes Redonda Island) AI Anguilla Anguilla AL Albania Republic of Albania AM Armenia Republic of Armenia Netherlands Antilles (includes Bonaire, Curacao, AN Netherlands Antilles Saba, St. Eustatius, and Southern St. Martin) AO Angola Republic of Angola (includes Cabinda) AQ Antarctica Territory south of 60 degrees south latitude AR Argentina Argentine Republic America Samoa (principal island Tutuila and AS American Samoa includes Swain's Island) AT Austria Republic of Austria Australia (includes Lord Howe Island, Macquarie Islands, Ashmore Islands and Cartier Island, and Coral Sea Islands are Australian external AU Australia territories) AW Aruba Aruba AX Aland Islands Aland Islands AZ Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina BB Barbados Barbados BD Bangladesh People's Republic of Bangladesh BE Belgium Kingdom of Belgium BF Burkina Faso Burkina Faso BG Bulgaria Republic of Bulgaria BH Bahrain Kingdom of Bahrain BI Burundi Republic of Burundi BJ Benin Republic of Benin BL Saint Barthelemy Saint Barthelemy BM Bermuda Bermuda BN Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam BO Bolivia Republic of Bolivia Federative Republic of Brazil (includes Fernando de Noronha Island, Martim Vaz Islands, and BR Brazil Trindade Island) BS Bahamas Commonwealth of the Bahamas BT Bhutan Kingdom of Bhutan -

Report for the 2002 Pacific Biological Survey, Bishop Museum Austral Islands, French Polynesia Expedition to Raivavae and Rapa Iti

Rapa K.R. Wood photo New Raivavae Damselfly Sicyopterus lagocephalus: Raivavae REPORT FOR THE 2002 PACIFIC BIOLOGICAL SURVEY, BISHOP MUSEUM AUSTRAL ISLANDS, FRENCH POLYNESIA EXPEDITION TO RAIVAVAE AND RAPA ITI Prepared for: Délégation à la Recherche (Ministère de la Culture, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche), B.P. 20981 Papeete, Tahiti, Polynésie française. Prepared by: R.A. Englund Pacific Biological Survey Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817 March 2003 Contribution No. 2003-004 to the Pacific Biological Survey 2002 Trip Report: Expedition to Raivavae and Rapa, Austral Islands, French Polynesia TABLE OF CONTENTS Résumé ..................................................................................................................................................................iii Abstract.................................................................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Study Area.............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Aquatic Habitats- Raivavae .............................................................................................................................. 3 Aquatic Habitats- Rapa.................................................................................................................................... -

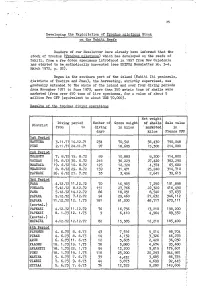

Developing the Exploitation of <I>Trochus Niloticus</I> Stock on the Tahiti Reefs

35 Developing the Exploitation of Trochu3 niloticus Stock onithe_Ta'hiti Reefs Readers of our Newsletter have already been informed that the stock of trochus (Trochug niloticus) which has developed on the reefs of Tahiti, from a few dozen specimens introduced in 1957 from Hew Caledonia has started to be methodically harvested (see SPIPDA Newsletter ITo. 3-4, March 1972, p. 32). Begun in the southern part of the island (Tahiti Iti peninsula, districts of Tautira and Pueu), the harvesting, strictly supervised, was gradually extended to the whole of the island and over four diving periods fjrom November 1971 to June 1973? more than 350 metric tons of shells were marketed (from over 450 tons of live specimens, for a value of about 5 million Frs CTP (equivalent to about US$ 70,000). Results of .the trochus. diving operations Net weight Diving period Number of Gross weight of shells Sale value District from to diving in kilos ' marketed in days kilos Francs CPP 1st Period TAUTIRA 3-11.71 I4.l2.7i 234 70,541 56,430 790,048 .. PUEU 2.11 .71 24.11.71 97 18,605 ... 15,300 214,000 2nd Period TOAHOTU 7. 8.72 15. 8,72 89 10r883 8,200 114,800 : VAIRAO 15. 8.72 30. 8.72 216 36J229 27,420 362,290 , MAATAIA. 19. 6.72 10. 8o72 125 12,724 4,374 65,600 TEAHUPOO 8. 8.72 29. 8.72 159 31,471 25,240' 314,710 PAPEARI 26. 6.72 27. 7.72 35 3,456 2,641 39,615 ; 3rd Period FAAA 4.12,72 11.12.72 70 16,983 7,250 101,898 PIMAAUA 5.12.72 8,12.72 151 27,766 .22,320 416,490 PAEA 5.12.72 14*12.72 86 18,051 8, 540 97,633 PAPARA 5.12.72 7.12.72 94 29,460 21,632 346,112 PAPARA 11.12.72 12. -

Marquesan Adzes in Hawai'i: Collections, Provenance

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 outside the Marquesas have never been found in the Marquesan Adzes in Hawai‘i: island group (Allen 2014:11), but this groundbreaking Collections, Provenance, and discovery was spoiled by the revelation that a yachtsman who had visited both places had donated the artifacts, Sourcing and apparently mixed them up before doing so (202). Hattie Le‘a Wheeler Gerrish Researchers with access to other sources of information Anthropology 484 can avoid possible pitfalls. Garanger (1967) laments, Fall 2014 “What amount of dispersed artifacts were illegally exported by the numerous voyagers drawn by the Abstract mirage of the “South Seas” and now irrevocably lost to In 1953, Jack and Leah Wheeler returned to science?” (390). It is my intent to honor the wishes of Hawai'i with 13 adze heads and one stone pounder my maternal grandparents, Jack and Leah Wheeler, that they had obtained during their travels in the Marquesas, the artifacts they (legally) brought home to Hawai'i from Tuamotus, and Society Islands. The rather general the East Pacific not be “irrevocably lost to science.” I provenance of these artifacts presents a challenge will attempt to source their stone artifacts, and discover that illustrates the benefits of combining XRF with what geochemistry can tell us of these tools of uncertain other sources of information, and the limits of current provenance. My experience strengthens my belief that knowledge of Pacific geochemistry. EDXRF reveals that combining non-destructive EDXRF with other sources five of the artifacts are likely made of stone from the of information such as oral history, written accounts, Eiao quarry, and the rest may represent five additional and morphological comparison, enhances the value of sources.