Space Modders: Learning from the Game Commune by Alex Kypriotakis-Weijers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 Apple Arcade Games to Play on Launch Day from Strategy to Action to Puzzle Games, Here’S Where You Should Head First

APPLE MOBILE GAMING 11 14 Apple Arcade games to play on launch day From strategy to action to puzzle games, here’s where you should head first By Russ Frushtick @RussFrushtick Sep 19, 2019, 9:40am EDT Simogo Games Today’s launch of Apple Arcade might be overwhelming to some players. Subscribers who drop $4.99 a month get unlimited access to a large swath of games, and scrolling through the list can feel a bit like trying to find something good to watch on Netflix. The initial launch line-up includes over 50 games, but we’ve gone ahead and narrowed them down to 14 titles you’d do well to check out first. WHAT THE GOLF? Triband/The Label While there are plenty of thoughtful, story-driven games in the Apple Arcade collection, What the Golf? goes another way. What starts as a simple miniature golf game quickly evolves into a bizarre blend of physics-based chaos. One level might have you sliding an office chair around the course while another has you knocking full-sized buildings into the pin. The pick-up-and-play nature makes it an easy recommendation for your first dive into Apple Arcade. ASSEMBLE WITH CARE It makes sense that Apple would work with usTwo on an Apple Arcade release title. After all, the developer is known as one of the most successful mobile game makers ever, thanks to Monument Valley and its sequel. usTwo’s latest title, Assemble with Care, taps into humans’ love of taking things apart and putting them back together. -

Olliolli2 Welcome to Olliwood Patch

1 / 2 OlliOlli2: Welcome To Olliwood Patch ... will receive a patch to implement these elements): Additional NPCs added for an ... OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood plucks the iconic skater from the street and .... Oct 31, 2016 — This is a small update to the original GOL game that greatly improves the ... Below is a list of updates. ... OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood.. Apr 27, 2020 — ... into the faster, more arcade-like titles like OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood, ... Related: Skate 4 Update: EA Gives Up Skate Trademark Only To .... End Space Quest 2 Update Brings 90Hz and More. ... 2 Bride of the New Moon PS4 pkg 5.05, OlliOlli2 Welcome to Olliwood Update v1.01 PS4-PRELUDE, 8-BIT .... Mar 3, 2015 — Those more subtle changes include new tricks to pull off, curved patches of ground, launch ramps, and split routes. It's not that these go unnoticed .... Aug 18, 2015 — I rari problemi di frame rate sono stati risolti con l'ultima patch, quindi non vale la pena dilungarsi a parlarne. L'unico appunto che possiamo fare .... Olliolli2: Welcome To Olliwood Free Download (v1.0.0.7). Indie ... Wallpaper Engine Free Download (Build 1.0.981 Incl. Workshop Patch) · Indie ... Apr 2, 2015 — ... scores on OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood seemed strange at launch. ... In the latest patch for the PlayStation 4, we have fixed the bug and .... Feb 27, 2016 — Welcome to the latest entry in our Bonus Round series, wherein we tell you all about the new Android games ... OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood.. Nov 22, 2020 — Following an update, you can now pet the dog in Hades pic. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Game Design Document: “Fear Tales”

GAME DESIGN DOCUMENT: “FEAR TALES” Equipe de Desenvolvedores: Grégory Faria de Oliveira RA 5125915 João Vitor Duarte Barcelos RA 5145128 Orientação Prof. Roberto de Assis UBERABA 2020 1. INTRODUÇÃO Este documento tem o intuito de apresentar o jogo Fear Tales com aspectos técnicos e artísticos do desenvolvimento. Será apresentado brevemente o enredo do jogo, sua mecânica, jogabilidade e ferramentas usadas no desenvolvimento. 1.1 RESUMO DA HISTÓRIA Kimi é uma garota de 11 anos presa em um mundo imaginário. Seu objetivo é resgatar seu melhor amigo Shinshi, que encontra-se aprisionado, para que juntos possam fugir de lá. Para isso, Kimi busca as 3 runas espalhadas pelo mundo capaz de libertar Shinshi, tendo que resolver enigmas e superar seu maior medo, a escuridão. 1.2 GAMEPLAY OVERVIEW A protagonista embarca em uma aventura de puzzles e exploração para descobrir como retomar controle do seu reino dos sonhos. Com esse intuito, o jogador terá de explorar cenários fantásticos, cheios de desafios e interações, em busca de pistas para concluir seu objetivo e seguir o caminho para superar seus medos e recuperar o mundo imaginário de Kimi. O jogo apresenta como desafios, na fase de demonstração, os puzzles e o tempo até que a escuridão tome conta de Kimi, fazendo com o que o jogador pense em sua estratégia de exploração. 1.3 GÊNERO, SEMELHANÇAS E DIFERENÇAS O projeto consiste em um jogo de puzzle e aventura em terceira pessoa, ambientado em um mundo lúdico com mescla de realidade e fantasia, combinado com traços de animações japonesas. Em jogabilidade o objetivo principal é a imersão divertida e envolvente, com mecânicas únicas e diferentes tipos de interações, o que proporciona uma experiência diferente dos demais jogos do gênero. -

Behavior Based Artificial Intelligence in a Village Environment

Teknik och samhälle Datavetenskap Examensarbete 15 högskolepoäng, grundnivå Behavior Based Artificial Intelligence in a Village Environment Beteendebaserad Artificiell Intelligens i en bymiljö Tim Lindstam Anton Svensson Examen: Kandidatexamen 180 hp Handledare: José María Font Huvudämne: Datavetenskap Examinator: Steve Dahlskog Program: Spelutveckling Template: www.emena.org/ Datum för slutseminarium: 2017-06-01 files/springerformat.doc Behavior Based Artificial Intelligence in a Village Environment Tim Lindstam, Anton Svensson Game Development Program, Computer Science and Media Technology, Malmö University, Sweden Abstract. Autonomous agents, also known as AI agents, are staples in modern video games. They take a lot of roles, everything from being quest-givers in roleplaying games, to opposing forces in action- and shooter games. Crafting an AI that is not only easy to create, but also retains humanlike and believable behavior, has always represented a challenge to the development industry, and has in several cases ended up with open world games using AI systems that limit the AI agents to simple moving patterns. In this thesis, a form of AI systems more commonly used in simulation games such as The Sims video game series, are taken and implemented in an environment that could possibly be seen in an open world game. After the implementation, a set of tests were performed on a group of testers which resulted in the insight that a majority of the testers, when asked to compare their experience to other games, found this implementation to feel more lifelike and realistic. Keywords: AI, game development, game AI, behavior tree 1 Introduction The world of games is not only inhabited by the players of video games, but also by autonomous agents. -

3D Character Artist

We are looking for: 3D CHARACTER ARTIST JOB DESCRIPTION Developing high detail, photorealistic 3D models (humanoid characters and other creatures) Creating clean, low-resolution game topology and UV’s Developing game-ready assets to match concept, photo reference, art direction, etc. Creating textures and next-gen materials for use in-game engine Exporting models and textures into in-house engine (Serious Engine 4.x) and making sure they work correctly Cleaning up scanned data REQUIREMENTS Experience with creating character / organic models (modeling and texturing) Proficiency in Zbrush or Mudbox Understanding of human and animal anatomy and clothing and a keen eye towards form, shape, structure and silhouette in regards to modeling Eye for light, shade, color, and detail in creating texture maps Good English communication skills (both written and spoken) Good judgment on when to make it perfect and when to compromise Passion about art and video games, and eagerness to grow BONUS POINTS Proficiency in one or more texturing software (Quixel, Substance Painter/Designer) Skills in one or more 3D modeling software (Blender, Modo, 3D Studio Max, Maya) Skills in hard-surface poly modeling techniques Baking pipeline and rendering experience Character concept art skills Previous experience in a 3D Artist role in the video game industry or TV/ film Skinning, rigging and animating skills Traditional sculpting, drawing or painting skills Understanding of the visual style of Croteam games and a passion to push it to the next -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

NG16 Program

C M Y CM MY CY CMY K PROGRAM 2016 #nordicgame Award-winning projects from Swiss indie studios Surprising Gamedesigns / Innovative Gameplay Late Shift Niche Booth Booth CtrlMovie AG Niche Game C2 lateshift-movie.com niche-game.com C4 Welcome to Nordic Game 2016: Knowledge, Emotion, Business. We are very proud to welcome you to three days of Knowledge, Emotion and Business. It’s the thirteenth edition of the conference, and it’s been Personal hectic, fun, challenging and inspiring to prepare it for you. Booth Photorealistic C5 Avatar SDK We look at this year’s show as sort of a reboot. We have focused heavily Dacuda AG dacuda.com on tweaking some essential parts, while maintaining the elements that we know you love and define as the special Nordic Game experience. As always, we’re more than happy to get feedback and input from you, because this show is as much yours as it is ours, and we want to keep on learning and improving. So, we hope you are ready to listen, talk, learn, share, build, connect, evolve, inspire, laugh, drink, eat, joke, be serious, have fun, be tired but also happy, and that you will enjoy NG16 as much as we enjoyed creating it. Thank you for joining us, and may you and your business prosper! The Nordic Game 2016 Team Booth World Never End Schlicht Booth C7 HeartQuake Studios Mr. Whale’s Game Service C8 heartquakestudios.com schlichtgame.ch NG16 TIME SCHEDULE We are 17 May PRE-CONFERENCE DAY 13:00 – 17:00 Badge pick-up 14:00 Game City Studio Tour pick-up 18 May CONFERENCE DAY 1 Join us to democratize 9:00 Badge pick-up -

PER MUDARRAGARRIDO TFG.Pdf

LOS VIDEOJUEGOS COMO HERRAMIENTA DE COMUNICACIÓN, EDUCACIÓN Y SALUD MENTAL RESUMEN Desde su sencillo origen en 1958 con Tennis For Two y su consiguiente auge en los años 80, la industria del videojuego se ha ido reinventando para hacer de la experiencia del jugador algo totalmente único. Es más que evidente la gran trascendencia de los videojuegos en nuestra sociedad actual, llegando a ser una de las industrias con más ganancias en los últimos años y una de las que más consigue mantener fieles a sus seguidores, debido a todas sus capacidades y aspectos beneficiosos más allá del entretenimiento. Por todo ello, entendemos que, si los videojuegos son un medio tan consolidado y con tanta trascendencia social en el ámbito del ocio, también pueden llegar a tener aplicaciones en otros ámbitos o disciplinas. Esta cuestión es la que va a ser tratada en nuestra investigación, exponiendo como objetivos el llegar a conocer las distintas aplicaciones de los videojuegos en otros ámbitos, debido a sus posibles aspectos beneficiosos (sin dejar de tener en cuenta los perjudiciales) y analizando el cómo son vistos a través de los ojos de una sociedad crítica. Para realizar la investigación nos hemos apoyado en juegos como Life is Strange, Gris o Celeste, así como en entrevistas y encuestas realizadas a una sección de la población. La principal conclusión que podemos sacar de la investigación es que: aunque el uso de los videojuegos no es una metodología muy acogida por los profesionales de la psicología, tiene un gran efecto positivo entre las personas que padecen algún tipo de trastorno psicológico o que ha sufrido acoso. -

EXTENDED FICTION in GAME DESIGN Austin Anderson (Michael Young) Department of Computer Science

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL UNMASKING THE PLAYER: EXTENDED FICTION IN GAME DESIGN Austin Anderson (Michael Young) Department of Computer Science INTRODUCTION In any story, an element being diegetic means that it is an element of the story that the characters of the fiction can sense. The simplest example is that of music in a movie; if there is a radio playing music in the scene, that music is diegetic. If a musical soundtrack plays over the scene but is something the characters cannot hear, it is non-diegetic(DIEGETIC). The border between the diegetic and non-diegetic is most commonly referred to as “the fourth wall” (Webster), in reference to the imaginary fourth wall of a play set, where the sides and back of the room that events are taking place in are fully represented on the theater stage, but the opening through which the audience observes the events of the play is an imaginary barrier. This barrier isn’t just literally a completion of the four walls in a traditional room of a building, but also metaphorically separates the reality from the fiction, quarantining both from each other as to not interfere. The problem with this boundary is that it can’t fully encompass the medium of video games. Video games, at their very essence, are an interactive medium. They require some breach of the fourth wall for them to function, as the game could not proceed to tell its story without a player’s input, which is an addressing of the audience due to the necessity of their action. -

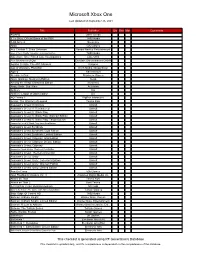

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc.