Papadopoulou Fot Thesis 2019.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal 2018

The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal 2018 Through subtle shades of color, the cover design represents the layers of richness and diversity that flourish within minority communities. The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal 2018 A collection of scholarly research by fellows of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program Preface We are proud to present to you the 2018 edition of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal. For more than 30 years, the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship (MMUF) program has endeavored to promote diversity in the faculty of higher education, specifically by supporting thousands of students from underrepresented minority groups in their goal of obtaining PhDs. With the MMUF Journal, we provide an additional opportunity for students to experience academia through exposure to the publishing process. In addition to providing an audience for student work, the journal offers an introduction to the publishing process, including peer review and editor-guided revision of scholarly work. For the majority of students, the MMUF Journal is their first experience in publishing a scholarly article. The 2018 Journal features writing by 27 authors from 22 colleges and universities that are part of the program’s member institutions. The scholarship represented in the journal ranges from research conducted under the MMUF program, introductions to senior theses, and papers written for university courses. The work presented here includes scholarship from a wide range of disciples, from history to linguistics to political science. The papers presented here will take the reader on a journey. Readers will travel across the U.S., from Texas to South Carolina to California, and to countries ranging from Brazil and Nicaragua to Germany and South Korea, as they learn about theater, race relations, and the refugee experience. -

The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children's Picturebooks

Strides Toward Equality: The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children’s Picturebooks Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebekah May Bruce, M.A. Graduate Program in Education: Teaching and Learning The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Michelle Ann Abate, Advisor Patricia Enciso Ruth Lowery Alia Dietsch Copyright by Rebekah May Bruce 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines nine narrative non-fiction picturebooks about Black American female athletes. Contextualized within the history of children’s literature and American sport as inequitable institutions, this project highlights texts that provide insights into the past and present dominant cultural perceptions of Black female athletes. I begin by discussing an eighteen-month ethnographic study conducted with racially minoritized middle school girls where participants analyzed picturebooks about Black female athletes. This chapter recognizes Black girls as readers and intellectuals, as well as highlights how this project serves as an example of a white scholar conducting crossover scholarship. Throughout the remaining chapters, I rely on cultural studies, critical race theory, visual theory, Black feminist theory, and Marxist theory to provide critical textual and visual analysis of the focal picturebooks. Applying these methodologies, I analyze the authors and illustrators’ representations of gender, race, and class. Chapter Two discusses the ways in which the portrayals of track star Wilma Rudolph in Wilma Unlimited and The Quickest Kid in Clarksville demonstrate shifting cultural understandings of Black female athletes. Chapter Three argues that Nothing but Trouble and Playing to Win draw on stereotypes of Black Americans as “deviant” in order to construe tennis player Althea Gibson as a “wild child.” Chapter Four discusses the role of family support in the representations of Alice Coachman in Queen of the Track and Touch the Sky. -

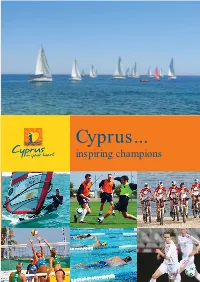

Visitcyprus.Com

Cyprus... inspiring champions “I found this training camp ideal. I must compliment the organisation and all involved for an excellent stay again. I highly recommend all professional teams to come to the island…” Gery Vink, Coach of Jong Ajax 1 Sports Tourism in Cyprus There are many reasons why athletes and sports lovers are drawn to the beautiful island of Cyprus… There’s the exceptional climate, the range of up-to-date sports facilities, the high-quality service industry, and the short travel times between city, sea and mountains. Cyprus offers a wide choice of sports facilities. From gyms Many international sports bodies have already recognized Cyprus to training grounds, from Olympic swimming pools to mountain as the ideal training destination. And it’s easy to see why National biking routes, there’s everything the modern sportsman or Olympic Committees from a number of countries have chosen woman could ask for. Cyprus as their pre-Olympic Games training destination. One of the world’s favourite holiday destinations, Cyprus also Medical care in Cyprus is of the highest standard, combining has an impressive choice of accommodation, from self-catering advanced equipment and facilities with the expertise of highly apartments to luxury hotels. When considering where to stay, it’s skilled practitioners. worth remembering that many hotels provide fully equipped The safe and friendly atmosphere also encourages athletes to fitness centres and health spas with qualified personnel - the bring families for an enjoyable break in the sun. Great restaurants, ideal way to train and relax. friendly cafes and great beaches make Cyprus the perfect place A gateway between Europe and the Middle East, Cyprus enjoys to unwind and relax. -

Fractured Circles of Race: a Heuristic Model for Teaching About Racial Categorization in Anthropological and Historical Perspective

Fractured Circles of Race 1 Fractured Circles of Race: A Heuristic Model for Teaching about Racial Categorization in Anthropological and Historical Perspective Robert Shanafelt Georgia Southern University This paper presents a heuristic model for teaching about human variation and transformations of concepts of race over time. It suggests that key aspects of the complexities related to the topic can be fruitfully discussed by making use of the image of a feedback loop between folk models and scientific models of human kinds and human variations. In order to elucidate this discussion, a brief review of the history of racial thinking and some current ideas about race, genetics, and biomedicine are also presented. Anthropology since its inception has been engaged in research and debate about the meaning and validity of racial categories. While the reality of race was once taken for granted, in recent years the view that “race is not an accurate or productive way to describe human biological variation” (Edgar and Hunley 2009: 2) has become widespread. Indeed, recent surveys and official statements from professional associations suggest that the pioneering critiques of traditional racial assumptions made by Franz Boas (1940 [1995]), Ashley Montague (1942 [2008]), and Frank Livingstone (1962) have been widely accepted among anthropologists in North America, although they have had uneven influence elsewhere (Lieberman et al. 2004; American Anthropological Association [AAA] 1998; American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 1996).1My concern here, though, is not to discuss this development in all its detail. Rather, it is to provide a manageable 1 Some have suggested that the consensus view in North America has begun to unravel with the advent of findings from current human genome research (A.M. -

The Cyprus Sport Organisation and the European Union

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................ 2 1. THE ESSA-SPORT PROJECT AND BACKGROUND TO THE NATIONAL REPORT ............................................ 4 2. NATIONAL KEY FACTS AND OVERALL DATA ON THE LABOUR MARKET ................................................... 8 3. THE NATIONAL SPORT AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY SECTOR ...................................................................... 13 4. SPORT LABOUR MARKET STATISTICS ................................................................................................... 26 5. NATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING SYSTEM .................................................................................. 36 6. NATIONAL SPORT EDUCATION AND TRAINING SYSTEM ....................................................................... 42 7. FINDINGS FROM THE EMPLOYER SURVEY............................................................................................ 48 8. REPORT ON NATIONAL CONSULTATIONS ............................................................................................ 85 9. NATIONAL CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................... 89 10. NATIONAL ACTION PLAN AND RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................... 92 BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Social Dialogue in Professional Football at European and National Level ( Cyprus and Italy )

The Social Dialogue in professional football at European and National Level ( Cyprus and Italy ) By Dimitra Theodorou Supervisor: Professor Dr. Roger Blanpain Second reader: Dr. S.F.H.Jellinghaus Tilburg University LLM International and European Labour Law TILBURG 2013 1 Dedicated to: My own ‘hero’, my beloved mother Arsinoe Ioannou and to the memory of my wonderful grandmother Androulla Ctoridou-Ioannou. Acknowledgments: I wish to express my appreciation and gratitude to my honored Professor and supervisor of this Master Thesis Dr. Roger Blanpain and to my second reader Dr. S.F.H.Jellinghaus for all the support and help they provided me. This Master Thesis would not have been possible if I did not have their guidance and valuable advice. Furthermore, I would like to mention that it was an honor being supervised by Professor Dr. R. Blanpain and have his full support from the moment I introduced him my topic until the day I concluded this Master Thesis. Moreover, I would like to address special thanks to Mr. Spyros Neofitides, the president of PFA, and Mr. Stefano Sartori, responsible for the trade union issues and CBAs in the AIC, for their excellent cooperation and willingness to provide as much information as possible. In addition, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Michele Colucci, who introduced me to Sports Law and helped me with my research by not only providing relevant publications, but also by introducing me to Mr. Stefano Sartori. Last but not least, I want to thank all my friends for their support and patience they have shown all these months. -

Brains Versus Brawn: an Analysis of Stereotyping and Racial Bias in National Football League Broadcasts

Brains versus Brawn: An Analysis of Stereotyping and Racial Bias in National Football League Broadcasts Pat Viklund Boston College February, 2009 Brains versus Brawn ii Table of Contents Abstract_______________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction____________________________________________________________ 1 Background of the Problem _______________________________________________ 4 Research Question ______________________________________________________ 8 Rationale ______________________________________________________________ 8 Review of the Literature _________________________________________________ 11 Methodology__________________________________________________________ 21 Findings______________________________________________________________ 26 Discussion____________________________________________________________ 34 Conclusion ___________________________________________________________ 42 Appendix_____________________________________________________________ 44 References____________________________________________________________ 48 Brains versus Brawn 1 Abstract This study analyzed prior research on racism and sports media as well as examined television broadcasts of 5 National Football League games. The intent of the study was to investigate the possibility of announcers conveying racial bias and stereotyping players during games. The study analyzed the difference in frequency of physical and cognitive/personal descriptors used by commentators in describing black and white players. It also explored the -

Black Athletes of Faith Engaged in United States

FAITH, ACTIVISM, AND SPORTS: BLACK ATHLETES OF FAITH ENGAGED IN UNITED STATES PROFESSIONAL TEAM SPORTS John H. Vaughn Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Doctor of Ministry program at Drew Theological School Course Mentors: Rev. Dr. Gary Simpson and Rev. Dr. Leonard Sweet March 15, 2021 i ABSTRACT FAITH, ACTIVISM, AND SPORTS: BLACK ATHLETES OF FAITH ENGAGED IN UNITED STATES PROFESSIONAL TEAM SPORTS John H. Vaughn Ebenezer Baptist Church, Atlanta, Georgia This project-thesis reflects upon the ways that the faith of Black athletes influences them to catalyze social change. It begins with a historical contextualization of faith, sports, and activism by peering through the lenses of Black athletes to explore the ways that their faith, sports, and activism have been experienced, shaped, and expressed over the years. Shifting from past to present, one-on-one interviews focus on contemporary Anti-Racist activism.1 Recommendations are provided concerning what it will take to grow Anti-Racist activism in professional sports to the next level of influence and impact. As a next step, I propose the establishment of a membership network for Black athletes that supports and nurtures their faith-rooted activism. My hypothesis assumes that the Anti-Racist, socially liberative activism of many Black professional athletes in the United States is animated by a faith that is rooted in 1 The American Baptist Churches USA Anti-Racism Task Force, https://www.abc-usa.org/2021/02/the- abcusa-anti-racism-task-force-a-call-to-just-action/Dr. Kimberle’ Crenshaw, leading scholar of critical race theory, defines Anti-Racism as the active dismantling of systems, privileges, and everyday practices that reinforce and normalize the contemporary dimensions of white dominance. -

Than a Game Understanding The

MORE THAN A GAME UNDERSTANDING THE SUBJECTIVITIES OF BLACK MALE ATHLETES THROUGH SPACE AND RACE AT A PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INSTITUTION by LATASHA SMITH-TYUS NIRMALA EREVELLES, COMMITTEE CHAIR NATALIE ADAMS BECKY ATKINSON AARON KUNTZ UTZ MCKNIGHT A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Educational Leadership, Policy, and Technology Studies in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2017 Copyright LaTasha Smith-Tyus 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Black male student athletes who attend Predominantly White Institutions or PWIs (Esposito, 2011) are afforded an opportunity to represent the institution through competitive sports; yet, they face many academic and personal challenges while they are doing so. Although much literature exists that examines the experiences of Black male student athletes and the forms of discrimination and racism they encounter, there is still a need for in-depth qualitative research that focuses on the daily lived experiences of Black male students and the different spaces they occupy at their PWI. Moreover, more exploration is needed into how the subjectivities they encounter within the spaces at their PWI constitute their identities. Within this research study, Black male athletes share their personal experiences of attending a PWI and occupying different spaces at the institution. Furthermore, their lived experiences (Ladson-Billings, 2009) offer insight into how they negotiate being a person of color at a PWI who is often praised for his athletic talents; yet at times he finds himself living as an racialized (Smith, Yosso & Solorzano, 2007) person because of his skin color. -

Current Controversies in Sports, Media, and Society

SNEAK PREVIEW For more information on adopting this title for your course, please contact us at: [email protected] or 800-200-3908 Current Controversies in Sports, Media, and Society Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher Angela Schultz, Senior Field Acquisitions Editor Carrie Montoya, Manager, Revisions and Author Care Tony Paese, Project Editor Jess Estrella, Senior Graphic Designer Danielle Gradisher, Licensing Associate Don Kesner, Interior Designer Natalie Piccotti, Director of Marketing Kassie Graves, Vice President of Editorial Jamie Giganti, Director of Academic Publishing Copyright © 2020 by Cognella, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information retrieval system without the written permission of Cognella, Inc. For inqui- ries regarding permissions, translations, foreign rights, audio rights, and any other forms of reproduction, please contact the Cognella Licensing Department at [email protected]. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Cover image Copyright © 2017 iStockphoto LP/OSTILL. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 978-1-5165-2276-7 (pbk) / 978-1-5165-2277-4 (br) 3970 Sorrento Valley Blvd., Ste. 500, San Diego, CA 92121 Current Controversies in Sports, -

American Renaissance There Is Not a Truth Existing Which I Fear Or Would Wish Unknown to the Whole World

American Renaissance There is not a truth existing which I fear or would wish unknown to the whole world. — Thomas Jefferson Vol. 10, No. 10 October 1999 The Biological Reality of Race Choice data are accumu- basic unit of classification in modern are different. Within the dog species it- taxonomy is the species. A species is self there are many varieties that are lating in a neglected field. usually said to consist of a set of indi- quite different in physiology and behav- viduals capable of interbreeding and pro- ior. The tiny Mexican Chihuahua, would by Glayde Whitney ducing fertile offspring. If the offspring have a hard time mating with an Irish are not healthy and fertile, then the par- Wolfhound, but they are considered to ace is a fascinating scientific sub- be of the same species. ject. Unfortunately, for more When wolves encounter dogs, they Rthan half of this century there has usually eat them. But sometimes they been a huge propaganda campaign to mate with them. When they mate it is drive it completely out of the sciences. almost always the male wolf with the And even though most of the race-de- female dog. The reverse is rare–male niers’ claims are nonsense or wildly spun dogs are almost never able to mate with half-truths, the vast majority of serious female wolves. The hybrid puppies are scientists have been taught their lesson. usually fully fertile, so by this defini- For a youngster, to deal with race from tion Canis lupus and Canis familiaris are a scientific perspective and risk the la- not different species. -

Study Guide 1

AA101 Fall 2005 STUDY GUIDE 1 Joseph L. Graves, Jr., The Race Myth: Why We Pretend Race Exists in America Chapter One: “How Biology Refutes Our Racial Myths” 1. What are the criteria that Graves outlines which can be used to determine whether or not a specific population is a distinct race, biologically speaking? 2. Why don’t any human populations qualify as distinct biological races? In what specific ways do they fail to meet the criteria outlined by Graves? 3. Why aren’t physical differences proof that races exist? 4. What are some factors/pressures that account for genetic/trait variation among humans? 5. What effect do you think the timing of the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 had on the interpretation and/or understanding of Darwin’s claim? Chapter Two: “Great is Our Sin: A Brief History of Racism” 6. What did 19th century naturalists/scientists view as the relationship between biological features and social position? 7. Why was the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species such a revolutionary work for its time? What was the central challenge that Darwin’s work posed to the thinking of his peers and the accepted ideas of the field? 8. What does Graves mean when he describes racist behavior as a “ghost of our evolutionary past”? 9. How Does Graves describe the relationship between biological evolution and cultural evolution? What is a meme? How and why is it replicated? How is this method of replication different from that of genes? Chapter Three: “Sexual Selection, Reproduction, and Social Dominance” 10.