Olfactory Receptor Family 7 Subfamily C Member 1 Is a Novel Marker Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WO 2019/068007 Al Figure 2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/068007 Al 04 April 2019 (04.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: (72) Inventors; and C12N 15/10 (2006.01) C07K 16/28 (2006.01) (71) Applicants: GROSS, Gideon [EVIL]; IE-1-5 Address C12N 5/10 (2006.0 1) C12Q 1/6809 (20 18.0 1) M.P. Korazim, 1292200 Moshav Almagor (IL). GIBSON, C07K 14/705 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) Will [US/US]; c/o ImmPACT-Bio Ltd., 2 Ilian Ramon St., C07K 14/725 (2006.01) P.O. Box 4044, 7403635 Ness Ziona (TL). DAHARY, Dvir [EilL]; c/o ImmPACT-Bio Ltd., 2 Ilian Ramon St., P.O. (21) International Application Number: Box 4044, 7403635 Ness Ziona (IL). BEIMAN, Merav PCT/US2018/053583 [EilL]; c/o ImmPACT-Bio Ltd., 2 Ilian Ramon St., P.O. (22) International Filing Date: Box 4044, 7403635 Ness Ziona (E.). 28 September 2018 (28.09.2018) (74) Agent: MACDOUGALL, Christina, A. et al; Morgan, (25) Filing Language: English Lewis & Bockius LLP, One Market, Spear Tower, SanFran- cisco, CA 94105 (US). (26) Publication Language: English (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, 62/564,454 28 September 2017 (28.09.2017) US AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, 62/649,429 28 March 2018 (28.03.2018) US CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, (71) Applicant: IMMP ACT-BIO LTD. -

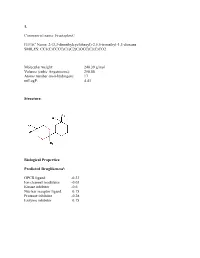

Sean Raspet – Molecules

1. Commercial name: Fructaplex© IUPAC Name: 2-(3,3-dimethylcyclohexyl)-2,5,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxane SMILES: CC1(C)CCCC(C1)C2(C)OCC(C)(C)CO2 Molecular weight: 240.39 g/mol Volume (cubic Angstroems): 258.88 Atoms number (non-hydrogen): 17 miLogP: 4.43 Structure: Biological Properties: Predicted Druglikenessi: GPCR ligand -0.23 Ion channel modulator -0.03 Kinase inhibitor -0.6 Nuclear receptor ligand 0.15 Protease inhibitor -0.28 Enzyme inhibitor 0.15 Commercial name: Fructaplex© IUPAC Name: 2-(3,3-dimethylcyclohexyl)-2,5,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxane SMILES: CC1(C)CCCC(C1)C2(C)OCC(C)(C)CO2 Predicted Olfactory Receptor Activityii: OR2L13 83.715% OR1G1 82.761% OR10J5 80.569% OR2W1 78.180% OR7A2 77.696% 2. Commercial name: Sylvoxime© IUPAC Name: N-[4-(1-ethoxyethenyl)-3,3,5,5tetramethylcyclohexylidene]hydroxylamine SMILES: CCOC(=C)C1C(C)(C)CC(CC1(C)C)=NO Molecular weight: 239.36 Volume (cubic Angstroems): 252.83 Atoms number (non-hydrogen): 17 miLogP: 4.33 Structure: Biological Properties: Predicted Druglikeness: GPCR ligand -0.6 Ion channel modulator -0.41 Kinase inhibitor -0.93 Nuclear receptor ligand -0.17 Protease inhibitor -0.39 Enzyme inhibitor 0.01 Commercial name: Sylvoxime© IUPAC Name: N-[4-(1-ethoxyethenyl)-3,3,5,5tetramethylcyclohexylidene]hydroxylamine SMILES: CCOC(=C)C1C(C)(C)CC(CC1(C)C)=NO Predicted Olfactory Receptor Activity: OR52D1 71.900% OR1G1 70.394% 0R52I2 70.392% OR52I1 70.390% OR2Y1 70.378% 3. Commercial name: Hyperflor© IUPAC Name: 2-benzyl-1,3-dioxan-5-one SMILES: O=C1COC(CC2=CC=CC=C2)OC1 Molecular weight: 192.21 g/mol Volume -

Functional Variability in the Human Odorant Receptor Repertoire

ART ic LE s The missense of smell: functional variability in the human odorant receptor repertoire Joel D Mainland1–3, Andreas Keller4, Yun R Li2,6, Ting Zhou2, Casey Trimmer1, Lindsey L Snyder1, Andrew H Moberly1,3, Kaylin A Adipietro2, Wen Ling L Liu2, Hanyi Zhuang2,6, Senmiao Zhan2, Somin S Lee2,6, Abigail Lin2 & Hiroaki Matsunami2,5 Humans have ~400 intact odorant receptors, but each individual has a unique set of genetic variations that lead to variation in olfactory perception. We used a heterologous assay to determine how often genetic polymorphisms in odorant receptors alter receptor function. We identified agonists for 18 odorant receptors and found that 63% of the odorant receptors we examined had polymorphisms that altered in vitro function. On average, two individuals have functional differences at over 30% of their odorant receptor alleles. To show that these in vitro results are relevant to olfactory perception, we verified that variations in OR10G4 genotype explain over 15% of the observed variation in perceived intensity and over 10% of the observed variation in perceived valence for the high-affinity in vitro agonist guaiacol but do not explain phenotype variation for the lower-affinity agonists vanillin and ethyl vanillin. The human genome contains ~800 odorant receptor genes that have RESULTS been shown to exhibit high genetic variability1–3. In addition, humans High-throughput screening of human odorant receptors exhibit considerable variation in the perception of odorants4,5, and To identify agonists for a variety of odorant receptors, we cloned a variation in an odorant receptor predicts perception in four cases: library of 511 human odorant receptor genes for a high-throughput loss of function in OR11H7P, OR2J3, OR5A1 and OR7D4 leads to heterologous screen. -

OR7C1 (NM 198944) Human Tagged ORF Clone Lentiviral Particle Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for RC216280L4V OR7C1 (NM_198944) Human Tagged ORF Clone Lentiviral Particle Product data: Product Type: Lentiviral Particles Product Name: OR7C1 (NM_198944) Human Tagged ORF Clone Lentiviral Particle Symbol: OR7C1 Synonyms: CIT-HSP-146E8; HSTPCR86P; OR7C4; OR19-5; TPCR86 Vector: pLenti-C-mGFP-P2A-Puro (PS100093) ACCN: NM_198944 ORF Size: 960 bp ORF Nucleotide The ORF insert of this clone is exactly the same as(RC216280). Sequence: OTI Disclaimer: The molecular sequence of this clone aligns with the gene accession number as a point of reference only. However, individual transcript sequences of the same gene can differ through naturally occurring variations (e.g. polymorphisms), each with its own valid existence. This clone is substantially in agreement with the reference, but a complete review of all prevailing variants is recommended prior to use. More info OTI Annotation: This clone was engineered to express the complete ORF with an expression tag. Expression varies depending on the nature of the gene. RefSeq: NM_198944.1, NP_945182.1 RefSeq Size: 963 bp RefSeq ORF: 963 bp Locus ID: 26664 UniProt ID: O76099, A0A126GWU6 Protein Families: Transmembrane Protein Pathways: Olfactory transduction MW: 35.5 kDa This product is to be used for laboratory only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. View online » ©2021 OriGene Technologies, Inc., 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200, Rockville, MD 20850, US 1 / 2 OR7C1 (NM_198944) Human Tagged ORF Clone Lentiviral Particle – RC216280L4V Gene Summary: Olfactory receptors interact with odorant molecules in the nose, to initiate a neuronal response that triggers the perception of a smell. -

Same As Figure 3 but for Mouse Protein-Coding Genes. 80 400 CODING - 40 200 PROTEIN

1000 100 10 average normalised counts per kilobase 0 0 1.1 2 3 4 5 7.5 11 gene length (kb) Supplementary Figure 1 | Same as Figure 3 but for mouse protein-coding genes. 80 400 CODING - 40 200 PROTEIN 0 0 40 80 20 40 PSEUDOGENES 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 number of transcript isoforms number of transcript isoforms Supplementary Figure 2 | Olfactory receptors have several isoforms per gene. Barplots of the number of genes with the indicated number of different transcript isoforms. Genes have been split into protein-coding (top) and pseu- dogenes (bottom), and by species (human on the right, mouse on the left). A Ifi47 Olfr56 BC147437.1 BC141219.1 AK133471.1 AK53352.1, BB664859.1 162 5 7 2 2 172 17 B Olfr115 Olfr116 AA543264.1 279 3 Gm18213 8 28 26 4 21 3 3 174 15 14 C Olfr139 Olfr399 CB271224.1 29 9 5 15 2 10 6 23 Supplementary Figure 3 | Same as Figure 4 but for the additional mouse ORs that share a 5’ UTR with a neighbour- ing gene. mRNA, EST or PacBio clones supporting splice junctions between the two genes are indicated above the corresponding transcript. A OR7C1 OR7A5 DA117551.1 DB071724.1, HY003914.1 DA444957.1 84 239 14 5 6 8 20 4 5 3 9 3 2 3 168 18 2 67 4 54 177 72 129 2 3 2 8 25 36 31 B OR5V1 OR11A1 AA936177.1 OR12D3 13 5 2 62 148 4 4 3 23 2 9 2 41 221 2 2 19 2 73 2 C HBE1 OR51B5 BC022184.1 BE789678.1 BE074228.1 Pacbio_capture_seq_hsK562 BM450021.1 BG496706.1, BF699214.1 7 3 2 7 4 2 4 3 Supplementary Figure 4 | Same as Figure 4 but for the additional human ORs that share a 5’ UTR with a neighbour- ing gene. -

Analysis of Single-Cell Transcriptomes Links Enrichment of Olfactory Receptors with Cancer Cell Differentiation Status and Prognosis

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01232-5 OPEN Analysis of single-cell transcriptomes links enrichment of olfactory receptors with cancer cell differentiation status and prognosis Siddhant Kalra1,7, Aayushi Mittal1,7, Krishan Gupta 1,2, Vrinda Singhal1, Anku Gupta2, Tripti Mishra3, ✉ ✉ 1234567890():,; Srivatsava Naidu4, Debarka Sengupta 1,2,5,6 & Gaurav Ahuja 1 Ectopically expressed olfactory receptors (ORs) have been linked with multiple clinically- relevant physiological processes. Previously used tissue-level expression estimation largely shadowed the potential role of ORs due to their overall low expression levels. Even after the introduction of the single-cell transcriptomics, a comprehensive delineation of expression dynamics of ORs in tumors remained unexplored. Our targeted investigation into single malignant cells revealed a complex landscape of combinatorial OR expression events. We observed differentiation-dependent decline in expressed OR counts per cell as well as their expression intensities in malignant cells. Further, we constructed expression signatures based on a large spectrum of ORs and tracked their enrichment in bulk expression profiles of tumor samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). TCGA tumor samples stratified based on OR-centric signatures exhibited divergent survival probabilities. In summary, our compre- hensive analysis positions ORs at the cross-road of tumor cell differentiation status and cancer prognosis. 1 Department of Computational Biology, Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology-Delhi (IIIT-Delhi), Okhla, Phase III, New Delhi 110020, India. 2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology-Delhi (IIIT-Delhi), Okhla, Phase III, New Delhi 110020, India. 3 Pathfinder Research and Training Foundation, 30/7 and 8, Knowledge Park III, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201308, India. -

Modélisation Des Mécanismes Moléculaires De La Perception Des Odeurs Claire De March

Modélisation des mécanismes moléculaires de la perception des odeurs Claire De March To cite this version: Claire De March. Modélisation des mécanismes moléculaires de la perception des odeurs. Autre. Université Nice Sophia Antipolis, 2015. Français. NNT : 2015NICE4068. tel-01432834 HAL Id: tel-01432834 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01432834 Submitted on 12 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE NICE-SOPHIA ANTIPOLIS - UFR Sciences Ecole Doctorale des Sciences Fondamentales et Appliquées T H E S E pour obtenir le titre de Docteur en Sciences de l'UNIVERSITE de Nice-Sophia Antipolis Discipline : Chimie présentée et soutenue par Claire de MARCH MODELISATION DES MECANISMES MOLECULAIRES DE LA PERCEPTION DES ODEURS Thèse dirigée par Jérôme GOLEBIOWSKI soutenue le 23 octobre 2015 Jury : Dr. Loïc BRIAND CSGA, Dijon Rapporteur Pr. Bernard OFFMANN Université de Nantes Rapporteur Dr. Moustafa BENSAFI Université Claude Bernard, Lyon Examinateur Pr. Xavier FERNANDEZ Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis Examinateur Dr. Gilles SICARD Université Aix-Marseille Examinateur Pr. Jérôme GOLEBIOWSKI Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis Directeur de thèse Remerciements Mes travaux de thèses ont été réalisés dans l’équipe Arôme, Parfum, Synthèse et Modélisation de l’Institut de Chimie de Nice sous la responsabilité du Professeur Jérôme Golebiowski. -

Explorations in Olfactory Receptor Structure and Function by Jianghai

Explorations in Olfactory Receptor Structure and Function by Jianghai Ho Department of Neurobiology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Hiroaki Matsunami, Supervisor ___________________________ Jorg Grandl, Chair ___________________________ Marc Caron ___________________________ Sid Simon ___________________________ [Committee Member Name] Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Neurobiology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 ABSTRACT Explorations in Olfactory Receptor Structure and Function by Jianghai Ho Department of Neurobiology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Hiroaki Matsunami, Supervisor ___________________________ Jorg Grandl, Chair ___________________________ Marc Caron ___________________________ Sid Simon ___________________________ [Committee Member Name] An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Neurobiology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Jianghai Ho 2014 Abstract Olfaction is one of the most primitive of our senses, and the olfactory receptors that mediate this very important chemical sense comprise the largest family of genes in the mammalian genome. It is therefore surprising that we understand so little of how olfactory receptors work. In particular we have a poor idea of what chemicals are detected by most of the olfactory receptors in the genome, and for those receptors which we have paired with ligands, we know relatively little about how the structure of these ligands can either activate or inhibit the activation of these receptors. Furthermore the large repertoire of olfactory receptors, which belong to the G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, can serve as a model to contribute to our broader understanding of GPCR-ligand binding, especially since GPCRs are important pharmaceutical targets. -

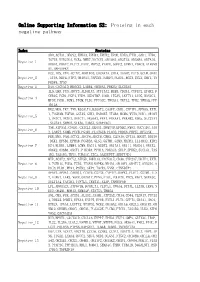

Online Supporting Information S2: Proteins in Each Negative Pathway

Online Supporting Information S2: Proteins in each negative pathway Index Proteins ADO,ACTA1,DEGS2,EPHA3,EPHB4,EPHX2,EPOR,EREG,FTH1,GAD1,HTR6, IGF1R,KIR2DL4,NCR3,NME7,NOTCH1,OR10S1,OR2T33,OR56B4,OR7A10, Negative_1 OR8G1,PDGFC,PLCZ1,PROC,PRPS2,PTAFR,SGPP2,STMN1,VDAC3,ATP6V0 A1,MAPKAPK2 DCC,IDS,VTN,ACTN2,AKR1B10,CACNA1A,CHIA,DAAM2,FUT5,GCLM,GNAZ Negative_2 ,ITPA,NEU4,NTF3,OR10A3,PAPSS1,PARD3,PLOD1,RGS3,SCLY,SHC1,TN FRSF4,TP53 Negative_3 DAO,CACNA1D,HMGCS2,LAMB4,OR56A3,PRKCQ,SLC25A5 IL5,LHB,PGD,ADCY3,ALDH1A3,ATP13A2,BUB3,CD244,CYFIP2,EPHX2,F CER1G,FGD1,FGF4,FZD9,HSD17B7,IL6R,ITGAV,LEFTY1,LIPG,MAN1C1, Negative_4 MPDZ,PGM1,PGM3,PIGM,PLD1,PPP3CC,TBXAS1,TKTL2,TPH2,YWHAQ,PPP 1R12A HK2,MOS,TKT,TNN,B3GALT4,B3GAT3,CASP7,CDH1,CYFIP1,EFNA5,EXTL 1,FCGR3B,FGF20,GSTA5,GUK1,HSD3B7,ITGB4,MCM6,MYH3,NOD1,OR10H Negative_5 1,OR1C1,OR1E1,OR4C11,OR56A3,PPA1,PRKAA1,PRKAB2,RDH5,SLC27A1 ,SLC2A4,SMPD2,STK36,THBS1,SERPINC1 TNR,ATP5A1,CNGB1,CX3CL1,DEGS1,DNMT3B,EFNB2,FMO2,GUCY1B3,JAG Negative_6 2,LARS2,NUMB,PCCB,PGAM1,PLA2G1B,PLOD2,PRDX6,PRPS1,RFXANK FER,MVD,PAH,ACTC1,ADCY4,ADCY8,CBR3,CLDN16,CPT1A,DDOST,DDX56 ,DKK1,EFNB1,EPHA8,FCGR3A,GLS2,GSTM1,GZMB,HADHA,IL13RA2,KIR2 Negative_7 DS4,KLRK1,LAMB4,LGMN,MAGI1,NUDT2,OR13A1,OR1I1,OR4D11,OR4X2, OR6K2,OR8B4,OXCT1,PIK3R4,PPM1A,PRKAG3,SELP,SPHK2,SUCLG1,TAS 1R2,TAS1R3,THY1,TUBA1C,ZIC2,AASDHPPT,SERPIND1 MTR,ACAT2,ADCY2,ATP5D,BMPR1A,CACNA1E,CD38,CYP2A7,DDIT4,EXTL Negative_8 1,FCER1G,FGD3,FZD5,ITGAM,MAPK8,NR4A1,OR10V1,OR4F17,OR52D1,O R8J3,PLD1,PPA1,PSEN2,SKP1,TACR3,VNN1,CTNNBIP1 APAF1,APOA1,CARD11,CCDC6,CSF3R,CYP4F2,DAPK1,FLOT1,GSTM1,IL2 -

Supplemental Table S18. Cellular Process Enrichment Analysis Output

Supplemental Table S18. -

Supplementary Methods

doi: 10.1038/nature06162 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Supplementary Methods Cloning of human odorant receptors 423 human odorant receptors were cloned with sequence information from The Olfactory Receptor Database (http://senselab.med.yale.edu/senselab/ORDB/default.asp). Of these, 335 were predicted to encode functional receptors, 45 were predicted to encode pseudogenes, 29 were putative variant pairs of the same genes, and 14 were duplicates. We adopted the nomenclature proposed by Doron Lancet 1. OR7D4 and the six intact odorant receptor genes in the OR7D4 gene cluster (OR1M1, OR7G2, OR7G1, OR7G3, OR7D2, and OR7E24) were used for functional analyses. SNPs in these odorant receptors were identified from the NCBI dbSNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP) or through genotyping. OR7D4 single nucleotide variants were generated by cloning the reference sequence from a subject or by inducing polymorphic SNPs by site-directed mutagenesis using overlap extension PCR. Single nucleotide and frameshift variants for the six intact odorant receptors in the same gene cluster as OR7D4 were generated by cloning the respective genes from the genomic DNA of each subject. The chimpanzee OR7D4 orthologue was amplified from chimpanzee genomic DNA (Coriell Cell Repositories). Odorant receptors that contain the first 20 amino acids of human rhodopsin tag 2 in pCI (Promega) were expressed in the Hana3A cell line along with a short form of mRTP1 called RTP1S, (M37 to the C-terminal end), which enhances functional expression of the odorant receptors 3. For experiments with untagged odorant receptors, OR7D4 RT and S84N variants without the Rho tag were cloned into pCI. -

OR7C1 (NM 198944) Human Tagged ORF Clone – RC216280 | Origene

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for RC216280 OR7C1 (NM_198944) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product data: Product Type: Expression Plasmids Product Name: OR7C1 (NM_198944) Human Tagged ORF Clone Tag: Myc-DDK Symbol: OR7C1 Synonyms: CIT-HSP-146E8; HSTPCR86P; OR7C4; OR19-5; TPCR86 Vector: pCMV6-Entry (PS100001) E. coli Selection: Kanamycin (25 ug/mL) Cell Selection: Neomycin ORF Nucleotide >RC216280 ORF sequence Sequence: Red=Cloning site Blue=ORF Green=Tags(s) TTTTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGGCCGGGAATTCGTCGACTGGATCCGGTACCGAGGAGATCTGCC GCCGCGATCGCC ATGGAAACAGGAAATCAAACACATGCCCAAGAATTTCTCCTCCTGGGATTTTCAGCAACGTCAGAGATTC AGTTCATTCTCTTTGGGCTGTTCCTCTCCATGTACCTAGTCACTTTCACCGGGAACCTGCTCATCATCCT GGCCATATGCTCAGACTCCCACCTCCACACCCCCATGTACTTCTTCCTCTCCAACCTGTCTTTTGCTGAC CTCTGTTTTACCTCCACGACTGTCCCAAAGATGTTACTGAATATACTGACACAGAACAAATTCATAACAT ATGCAGGCTGTCTCAGTCAGATTTTTTTTTTCACTTCATTTGGATGCCTGGACAATTTACTCTTGACCGT GATGGCCTATGACCGCTTCGTGGCCATCTGTCACCCCCTGCACTATACGGTCATCATGAACCCCCAGCTC TGTGGACTGCTGGTTCTGGGGTCCTGGTGCATCAGTGTCATGGGTTCCCTGCTCGAGACCTTGACTGTTT TGAGGCTGTCCTTCTGCACCAAAATGGAAATTCCACACTTTTTTTGTGATCTACTTGAAGTCCTGAAGCT CGCCTGTTCTGACACCTTCATTAATAACGTGGTGATATACTTTGCAACTGGCGTCCTGGGTGTGATTTCC TTCACTGGAATATTTTTCTCTTACTATAAAATTGTTTTCTCTATACTGAGGATTTCCTCAGCTGGGAGAA AGCACAAAGCGTTTTCCACCTGTGGTTCCCACCTCTCAGTGGTCACCTTGTTCTATGGCACGGGCTTTGG GGTCTATCTCAGTTCTGCAGCCACACCATCTTCTAGGACAAGTCTGGTGGCCTCAGTGATGTACACCATG