Fear and Othering in Delhi: Assessing Non-Belonging of Kashmiri Muslims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June Ank 2016

The Specter of Emergency Continues to Haunt the Country Mahi Pal Singh Forty one years ago this country witnessed people had been detained without trial under the the darkest chapter in the history of indepen- repressive Maintenance of Internal Security Act dent and democratic India when the state of (MISA), several high courts had given relief to emergency was proclaimed on the midnight of the detainees by accepting their right to life and 25th-26th June 1975 by Indira Gandhi, the then personal liberty granted under Article 21 and ac- Prime Minister of the country, only to satisfy cepting their writs for habeas corpus as per pow- her lust for power. The emergency was declared ers granted to them under Article 226 of the In- when Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha of the dian constitution. This issue was at the heart of Allahabad High Court invalidated her election the case of the Additional District Magistrate of to the Lok Sabha in June 1975, upholding Jabalpur v. Shiv Kant Shukla, popularly known charges of electoral fraud, in the case filed by as the Habeas Corpus case, which came up for Raj Narain, her rival candidate. The logical fol- hearing in front of the Supreme Court in Decem- low up action in any democratic country should ber 1975. Given the important nature of the case, have been for the Prime Minister indicted in the a bench comprising the five senior-most judges case to resign. Instead, she chose to impose was convened to hear the case. emergency in the country, suspend fundamen- During the arguments, Justice H.R. -

Jammu and Kashmir Directorate of Information Accredited Media List (Jammu) 2017-18 S

Government of Jammu and Kashmir Directorate of Information Accredited Media List (Jammu) 2017-18 S. Name & designation C. No Agency Contact No. Photo No Representing Correspondent 1 Mr. Gopal Sachar J- Hind Samachar 01912542265 Correspondent 236 01912544066 2 Mr. Arun Joshi J- The Tribune 9419180918 Regional Editor 237 3 Mr. Zorawar Singh J- Freelance 9419442233 Correspondent 238 4 Mr. Ashok Pahalwan J- Scoop News In 9419180968 Correspondent 239 0191-2544343 5 Mr. Suresh.S. Duggar J- Hindustan Hindi 9419180946 Correspondent 240 6 Mr. Anil Bhat J- PTI 9419181907 Correspondent 241 7 S. Satnam Singh J- Dainik Jagran 941911973701 Correspondent 242 91-2457175 8 Mr. Ajaat Jamwal J- The Political & 9419187468 Correspondent 243 Business daily 9 Mr. Mohit Kandhari J- The Pioneer, 9419116663 Correspondent 244 Jammu 0191-2463099 10 Mr. Uday Bhaskar J- Dainik Bhaskar 9419186296 Correspondent 245 11 Mr. Ravi Krishnan J- Hindustan Times 9419138781 Khajuria 246 7006506990 Principal Correspondent 12 Mr. Sanjeev Pargal J- Daily Excelsior 9419180969 Bureau Chief 247 0191-2537055 13 Mr. Neeraj Rohmetra J- Daily Excelsior 9419180804 Executive Editor 248 0191-2537901 14 Mr. J. Gopal Sharma J- Daily Excelsior 9419180803 Special Correspondent 249 0191-2537055 15 Mr. D. N. Zutshi J- Free-lance 88035655773 250 16 Mr. Vivek Sharma J- State Times 9419196153 Correspondent 251 17 Mr. Rajendra Arora J- JK Channel 9419191840 Correspondent 252 18 Mr. Amrik Singh J- Dainik Kashmir 9419630078 Correspondent 253 Times 0191-2543676 19 Ms. Suchismita J- Kashmir Times 9906047132 Correspondent 254 20 Mr. Surinder Sagar J- Kashmir Times 9419104503 Correspondent 255 21 Mr. V. P. Khajuria J- J. N. -

Khalistan & Kashmir: a Tale of Two Conflicts

123 Matthew Webb: Khalistan & Kashmir Khalistan & Kashmir: A Tale of Two Conflicts Matthew J. Webb Petroleum Institute _______________________________________________________________ While sharing many similarities in origin and tactics, separatist insurgencies in the Indian states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have followed remarkably different trajectories. Whereas Punjab has largely returned to normalcy and been successfully re-integrated into India’s political and economic framework, in Kashmir diminished levels of violence mask a deep-seated antipathy to Indian rule. Through a comparison of the socio- economic and political realities that have shaped the both regions, this paper attempts to identify the primary reasons behind the very different paths that politics has taken in each state. Employing a distinction from the normative literature, the paper argues that mobilization behind a separatist agenda can be attributed to a range of factors broadly categorized as either ‘push’ or ‘pull’. Whereas Sikh separatism is best attributed to factors that mostly fall into the latter category in the form of economic self-interest, the Kashmiri independence movement is more motivated by ‘push’ factors centered on considerations of remedial justice. This difference, in addition to the ethnic distance between Kashmiri Muslims and mainstream Indian (Hindu) society, explains why the politics of separatism continues in Kashmir, but not Punjab. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Of the many separatist insurgencies India has faced since independence, those in the states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have proven the most destructive and potent threats to the country’s territorial integrity. Ostensibly separate movements, the campaigns for Khalistan and an independent Kashmir nonetheless shared numerous similarities in origin and tactics, and for a brief time were contemporaneous. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Author(s): Haley Duschinski Source: International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Apr., 2008), pp. 41-64 Published by: Springer Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40343840 Accessed: 12-01-2020 07:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Hindu Studies This content downloaded from 134.114.107.39 on Sun, 12 Jan 2020 07:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Haley Duschinski Kashmiri Hindus are a numerically small yet historically privileged cultural and religious community in the Muslim- majority region of Kashmir Valley in Jammu and Kashmir State in India. They all belong to the same caste of Sarasvat Brahmanas known as Pandits. In 1989-90, the majority of Kashmiri Hindus living in Kashmir Valley fled their homes at the onset of conflict in the region, resettling in towns and cities throughout India while awaiting an opportunity to return to their homeland. -

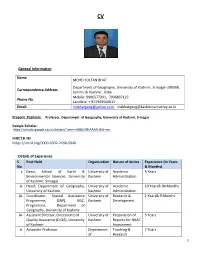

General Information Name MOHD SULTAN BHAT Correspondence Address Department of Geography, University of Kashmir, Srinagar-19000

CV General Information Name MOHD SULTAN BHAT Department of Geography, University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006, Correspondence Address Jammu & Kashmir, India Mobile: 9906577391, 7006837122 Phone No. Landline: + 911943560615 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Present Position: Professor, Department of Geography, University of Kashmir, Srinagar Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.co.in/citations?user=yHBbV9EAAAAJ&hl=en ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2198-5940 Details of Experience S Post Held Organization Nature of duties Experience (In Years No. & Months) i. Dean, School of Earth & University of Academic 3 Years Environmental Sciences, University Kashmir Administration of Kashmir, Srinagar ii. Head, Department of Geography, University of Academic 10 Years& 04 Months University of Kashmir Kashmir Administration iii. Coordinator, Special Assistance University of Research & 2 Years& 9 Months Programme, (SAP), UGC, Kashmir Development Programme, Department of Geography, University of Kashmir iv. Assistant Director, Directorate of University of Preparation of 3 Years Quality Assurance (DIQA), University Kashmir Reports for NAAC of Kashmir Assessment v. Associate Professor Department Teaching & 7 Years of Research 1 Geography, University of Kashmir vi. Assistant Professor Department Teaching & 13 Years of Research Geography , University of Kashmir Educational Qualification S. No. Qualification University Year i. Ph. D University of Kashmir 1995 ii. M. Phil University of Kashmir 1989 iii. Post-Graduation University of Kashmir 1986 Administrative Experience/Post(s) &Responsibilities held S Post Organization/ Duration No. University From To (Date) (Date) i. Head of the Department of Geography , University of 01.07.20006 04-02-2014 Department Kashmir & 05-02-2017 09-09-2019 ii. Chairman, Chairman Board of Postgraduate 01.07.20006 04-02-2014 Board of Studies, Department of Geography, & Studies University of Kashmir 05-02-2017 09-09-2019 iii. -

The First National Conference Government in Jammu and Kashmir, 1948-53

THE FIRST NATIONAL CONFERENCE GOVERNMENT IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 1948-53 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY BY SAFEER AHMAD BHAT Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2019 CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Safeer Ahmad Bhat, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, certify that the work embodied in this Ph.D. thesis is my own bonafide work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Ishrat Alam at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. The matter embodied in this Ph.D. thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. I declare that I have faithfully acknowledged, given credit to and referred to the researchers wherever their works have been cited in the text and the body of the thesis. I further certify that I have not willfully lifted up some other’s work, para, text, data, result, etc. reported in the journals, books, magazines, reports, dissertations, theses, etc., or available at web-sites and included them in this Ph.D. thesis and cited as my own work. The manuscript has been subjected to plagiarism check by Urkund software. Date: ………………… (Signature of the candidate) (Name of the candidate) Certificate from the Supervisor Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. Prof. Ishrat Alam Professor, CAS, Department of History, AMU (Signature of the Chairman of the Department with seal) COURSE/COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION/PRE- SUBMISSION SEMINAR COMPLETION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. -

The Kashmir Dispute: a Case Study of United Nations Action in Handling an International Dispute

THE KASHMIR DISPUTE: A CASE STUDY OF UNITED NATIONS ACTION IN HANDLING AN INTERNATIONAL DISPUTE By MAHMUD AHMAD FAKSH 'I Bachelor of .Arts American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon 1965 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS July, 1967 tlKLA!-lOMA Sif."T~ UN.VERSllY Lt 3·~A~Y JAN j,O 1968 THE. KASHMIR DISPUTE: A CASE STUDY OF UNITED NATIONS ACTION IN HANDLING AN INTERNATIONAL DISPUTE Thesis Approved: 658726 ii PREFACE The maintenance of international peace and security is the United Nations' most important function and the success or failure of the organ ization will be judged by the degree of success achieved in this endeav or. The United Nations has dealt with a number of international disputes and an analysis of its record should throw some light on both the opera tions and the value of the United Nations. In this thesis I will limit myself to the study of United Nations' actions in the Kashmir dispute to discuss an international action in the field of peaceful settlement. Indebtedness is acknowledged first to Dr. Raymond Habiby. my thesis adviser, who has worked tirelessly and unceasingly, to assist me in this study. I owe an incalculable debt to Dr. Clifford A. L. Rich, who was the first to arouse and guide my interest in the political and legal af fairs of men and nations. I am grateful to Professor Harold Sare for the valuable time he dedicated to the shaping and crystalization of my viewpoints. -

Making Borders Irrelevant in Kashmir Will Be Swift and That India-Pakistan Relations Will Rapidly Improve Could Lead to Frustrations

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T P. R. Chari and Hasan Askari Rizvi This report analyzes the possibilities and practicalities of managing the Kashmir conflict by “making borders irrelevant”—softening the Line of Control to allow the easy movement of people, goods, and services across it. The report draws on the results of a survey of stakeholders and Making Borders public opinion on both sides of the Line of Control. The results of that survey, together with an initial draft of this report, were shown to a group of opinion makers in both countries (former bureaucrats and diplomats, members of the irrelevant in Kashmir armed forces, academics, and members of the media), whose comments were valuable in refining the report’s conclusions. P. R. Chari is a research professor at the Institute Summary for Peace and Conflict Studies in New Delhi and a former member of the Indian Administrative Service. Hasan Askari • Neither India nor Pakistan has been able to impose its preferred solution on the Rizvi is an independent political and defense consultant long-standing Kashmir conflict, and both sides have gradually shown more flexibility in Pakistan and is currently a visiting professor with the in their traditional positions on Kashmir, without officially abandoning them. This South Asia Program of the School of Advanced International development has encouraged the consideration of new, creative approaches to the Studies, Johns Hopkins University. management of the conflict. This report was commissioned by the Center • The approach holding the most promise is a pragmatic one that would “make for Conflict Mediation and Resolution at the United States borders irrelevant”—softening borders to allow movement of people, goods, and Institute of Peace. -

Identification and Mapping of Religious Tourist Resources in Kashmir Valley Manjula Chaudhary*, Naser Ul Islam**

International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems Volume 13 Issue 1 June 2020 ISSN: 0974-6250 (Print) ©Copyright IJHTS ® Exclusive Marketing Rights: Publishing India Group Identification and Mapping of Religious Tourist Resources in Kashmir Valley Manjula Chaudhary*, Naser Ul Islam** Abstract Religious tourism is modern day format of pilgrimage. Pilgrimage is an old practice of travelling to the sacred places such as temples, mosques, churches and shrines etc. Religious tourism mixes pilgrimage and features of tourism and is considered a tool for sustainability, change and peace building among communities. It is particularly important for India being the fastest growing segment of tourism and given the fact that the whole country is dotted with important religious sites and is known for largest congregation in the world as in the case of Mahakumbh. While each state of country has a unique mix of religious tourism but the state of Jammu and Kashmir have a wonderful mix of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh religions sites though it is known more for Vaishno Devi shrine and Amarnath yatra. Kashmir Valley in this state is popularly known for its natural beauty and leisure tourism than religious tourism despite the high resources for religious tourism. This study is an attempt to identify and map the religious tourist resources in Kashmir valley. The nature of the study is exploratory and to find answers to queries raised through objectives both primary and secondary data has been used. The mapping of the sites highlighted that Kashmir has a mixture of different religious attractions and some of these attractions are located in close vicinity to one another. -

The Very Foundation, Inauguration and Expanse of Sufism: a Historical Study

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 5 S1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy September 2015 The Very Foundation, Inauguration and Expanse of Sufism: A Historical Study Dr. Abdul Zahoor Khan Ph.D., Head, Department of History & Pakistan Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty Block #I, First Floor, New Campus Sector#H-10, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan; Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Muhammad Tanveer Jamal Chishti Ph.D. Scholar-History, Department of History &Pakistan Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty Block #I, First Floor New Campus, Sector#H-10, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan; Email: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s1p382 Abstract Sufism has been one of the key sources to disseminate the esoteric aspects of the message of Islam throughout the world. The Sufis of Islam claim to present the real and original picture of Islam especially emphasizing the purity of heart and inner-self. To realize this objective they resort to various practices including meditation, love with fellow beings and service for mankind. The present article tries to explore the origin of Sufism, its gradual evolution and culmination. It also seeks to shed light on the characteristics of the Sufis of the different periods or generations as well as their ideas and approaches. Moreover, it discusses the contributions of the different Sufi Shaykhs as well as Sufi orders or Silsilahs, Qadiriyya, Suhrwardiyya, Naqshbandiyya, Kubraviyya and particularly the Chishtiyya. Keywords: Sufism, Qadiriyya, Chishtiyya, Suhrwardiyya, Kubraviyya-Shattariyya, Naqshbandiyya, Tasawwuf. 1. Introduction Sufism or Tasawwuf is the soul of religion. -

Curfew Relaxed in Kashmir Valley Only Way out of Kashmir Issue: CM

www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com Volthe No: XXI|Issue No. 203 |northlines 30.08.2016 ( Tuesday) |Daily | Price ` 2/-| Jammu Tawi | Pages-12 |Regd. No. JK|306|2014-16 Dialogue on Vajpayee's vision is the Curfew relaxed in Kashmir valley only way out of Kashmir Issue: CM NL Correspondent addressing a function after should understand that the Few stone pelting incidents, situation under Control: JKP Jammu Tawi, Aug 29 inaugurating the Food solution was not going to NL Correspondent vehicles. Crafts Institute in the come through violence. She Continuing her stand that Srinagar, Aug 29 Witnesses told that in Dhammi area of Nagrota. said violence had changed violence is not a solution to Srinagar's Batamaloo area Mehbooba said Prime nothing on the political any issue, Chief Minister Though the curfew and several youth appeared on Minister Narendra Modi spectrum of Jammu and Mehbooba Mufti today said restrictions were lifted from roads on this morning and had the mandate to take Kashmir over the years and that peace and dialogue was the Valley barring three erected temporary bold decisions on the lines had only brought mayhem, the only way forward areas falling under the barricades on roads to of Vajpayee's doctrine for miseries, economic disaster, towards addressing the jurisdiction of M R Gunj, disrupt the vehicular the resolution of the academic breakdown and Kashmir imbroglio. Nowhatta and in Pulwama movement during which problems in and around social disorder to the state. She emphasized on the town, the situation in most forces tried to disperse the Jammu and Kashmir.