Trans-Pacific Dialogue: Constructing Indigenous Identity in Contemporary Northern Native American and Taiwanese Indigenous Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Kanakanavu an Ergative Language?

Voice and transitivity in Kanakanavu Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Erfurt vorgelegt von Ilka Wild Erfurt, März 2018 Gutachter der Arbeit: Prof. Dr. Christian Lehmann, Universität Erfurt Prof. Dr. Volker Gast, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Datum der Defensio: 6. August 2018 Universitätsbibliothek Erfurt Electronic Text Center URN:nbn:de:gbv:547-201800530 Abstract This is a dissertation on the Kanakanavu language, i.e. that linguistic phenomena found while working on the language underwent a deeper analysis and linguistic techniques were used to provide data and to present analyses in a structured manner. Various topics of the Kanakanavu language system are exemplified: Starting with a grammar sketch of the language, the domains phonology, morphology, and syntax are described and information on the linguistic features in these domains are given. Beyond a general overview of the situation and a brief description of the language and its speakers, an investigation on a central part of the Kanakanavu language system, namely its voice system, can be found in this work. First, it is analyzed and described by its formal characteristics. Second, the question of the motivation of using the voice system in connection to transitivity and, in the literature less often recognized, the semantic side of transitive constructions, i.e. its effectiveness, is discussed. Investigations on verb classes in Kanakanavu and possible semantic connections are presented as well as investigations on possible situations of different degrees of effectiveness. This enables a more detailed view on the language system and, in particular, its voice system. -

Directory of Head Office and Branches Foreword

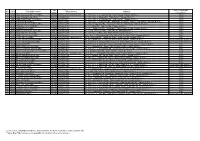

Directory of Head Office and Branches Foreword I. Domestic Business Units 20 Sec , Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng District, Taipei City 0007, Taiwan (R.O.C.) P.O. Box 5 or 305, Taipei, Taiwan Introduction SWIFT: BKTWTWTP http://www.bot.com.tw TELEX: 1120 TAIWANBK CODE OFFICE ADDRESS TELEPHONE FAX Department of 20 Sec , Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng District, 0037 02-23493399 02-23759708 Business Taipei City Report Corporate Department of Public 20 Sec , Gueiyang Street, Jhongjheng District, Taipei 0059 02-236542 02-23751125 Treasury City 58 Sec , Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng District, Governance 0082 Department of Trusts 02-2368030 02-2382846 Taipei City Offshore Banking 069 F, 3 Baocing Road, Jhongjheng District, Taipei City 02-23493456 02-23894500 Branch Department of 20 Sec , Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng District, Fund-Raising 850 02-23494567 02-23893999 Electronic Banking Taipei City Department of 2F, 58 Sec , Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng 698 02-2388288 02-237659 Securities District, Taipei City Activities 007 Guancian Branch 49 Guancian Road, Jhongjheng District, Taipei City 02-2382949 02-23753800 0093 Tainan Branch 55 Sec , Fucian Road, Central District, Tainan City 06-26068 06-26088 40 Sec , Zihyou Road, West District, Taichung City 04-2222400 04-22224274 Conditions 007 Taichung Branch General 264 Jhongjheng 4th Road, Cianjin District, Kaohsiung 0118 Kaohsiung Branch 07-2553 07-2211257 City Operating 029 Keelung Branch 6, YiYi Road, Jhongjheng District, Keelung City 02-24247113 02-24220436 Chunghsin New Village -

No 17 Taiwan, Province of China

AN ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, NATIONAL LEGISLATION, JUDGEMENTS, AND INSTITUTIONS AS THEY INTERRELATE WITH TERRITORIES AND AREAS CONSERVED BY INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES REPORT NO. 17 TAIWAN 0 “Land is the foundation of the lives and cultures of Indigenous peoples all over the world… Without access to and respect for their rights over their lands, territories and natural resources, the survival of Indigenous peoples’ particular distinct cultures is threatened.” Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Report on the Sixth Session 25 May 2007 Authored by: Dau-Jye Lu, Taiban Sasala and Chih-Liang Chao, in cooperation with the Tao Foundation Published by: Natural Justice in Bangalore and Kalpavriksh in Pune and Delhi Date: September 2012 Cover Photo: Ten oars plank boat. © Si Ngahephep, Tao Foundation 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: …........................................................................................................3 PART I: COUNTRY, COMMUNITIES AND ICCAs ........................................................... 3 1.1 Country (or subnational region) ................................................................................ 4 1.2 Communities & Environmental Change ..................................................................... 5 PART II: LAND, FRESHWATER AND MARINE LAWS & POLICIES ................................... 9 2.1 Land ............................................................................................................................. 10 2.2 Natural Resource Management .................................................................................. -

No. Area Post Office Name Zip Code Telephone No. Address Same Day

Zip Same Day Flight No. Area Post Office Name Telephone No. Address Code Cutoff Time* 1 Yilan Yilan Jhongshan Rd. Post Office 26044 (03)9324-133 (03)9326-727 No. 130, Sec. 3, Jhongshan Rd., Yilan 260-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:30 2 Yilan Yilan Jinlioujie Post Office 26051 (03)9368-142 No. 100, Sec. 3, Fusing Rd., Yilan 260-51, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:10 3 Yilan Yilan Weishuei Rd. Post Office 26047 (03)9325-072 No. 275, Sec. 2, Jhongshan Rd., Yilan 260-47, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:20 4 Yilan Yuanshan Post Office 26441 (03)9225-073 No. 299, Sec. 1, Yuanshan Rd., Yuanshan Township, Yilan County 264-41, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 11:50 5 Yilan Yuanshan Neicheng Post Office 26444 (03)9221-096 No. 353, Rongguang Rd., Yuanshan, Yilan County 264-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 11:40 6 Yilan Yilan Sihou St. Post Office 26044 (03)9329-185 No. 2-1, Sihou St., Yilan 260-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:20 7 Yilan Jhuangwei Post Office 26344 (03)9381-705 No. 327, Jhuang 5th Rd., Jhuangwei, Yilan County 263-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:00 8 Yilan Yilan Donggang Rd. Post Office 26057 (03)9385-638 No. 32-30, Donggang Rd., Yilan 260-57, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:10 9 Yilan Yilan Dapo Rd. Post Office 26054 (03)9283-195 No. 225, Sec. 2, Dapo Rd., Yilan 260-54, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 11:40 10 Yilan Yilan University Post Office 26047 (03)9356-052 No.1, Sec. -

Taiwan's Pension Crisis

NOTES On 24 November 2018, the ruling DPP won Taiwan’s Pension Crisis only six of the 22 city mayor and county commissioner seats in local elections. The opposition KMT gained a substantial 15 Chien-Hsun Chen seats. Future generations of taxpayers will shoulder the pension spending on current With the emergence of emocratisation has sown the generations if the pension system is not democratisation in Taiwan, seeds of Taiwan’s pension prob- made sustainable, for which a prerequi- political parties compete over Dlems, with political parties com- site is an end to low economic growth. peting over social welfare and pension Taiwan’s pension system, based on social welfare and pension benefi ts to please voters. Government the World Bank’s multi-pillar system benefi ts to please voters. Voters employees and other workers are covered (Holzmann and Hinz 2005), has fi ve want substantial increases in under different pension schemes. Taiwan’s pillars (Table 1). social welfare and pension generous pension system will not be The non-contributory “zero or basic affordable when its economy is growing pillar” for the social welfare programmes benefi ts but are fi ercely resistant at a low growth rate. Furthermore, a covers the (i) medium-income elderly to tax increases. Taiwan’s rapidly ageing population became a press- living allowance (NT$3,600 per month) government debt has continued ing demographic issue in Taiwan in the and low-income elderly living allow- NT to accumulate considerably. 1990s due to industrial transformation, ance ( $7,000 per month), (ii) old-age family planning, and urbanisation in the farmer’s welfare allowance (NT$7,000 per The Ministry of Civil Service 1970s and 1980s. -

TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS of SOCIAL and CULTRUAL IMPACTS of TOURISM in LAN-YU, TAIWAN Cheng-Hsuan Hsu Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2006 TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN Cheng-hsuan Hsu Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Recommended Citation Hsu, Cheng-hsuan, "TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN" (2006). All Theses. 47. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAO RESIDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN _________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Park, Recreation, and Tourism Management _________________________________________________________ by Cheng-Hsuan Hsu December 2006 _________________________________________________________ Accepted by: Dr. Kenneth F. Backman, Committee Chair Dr. Sheila J. Backman Dr. Francis A. McGuire ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to investigate residents’ perceptions of the social and cultural impacts of tourism on Lan-Yu (Orchid Island). More specifically, this study examines Lan-Yu’s aboriginal residents’ (The Tao) perceptions of social and cultural impacts of tourism. Systematic sampling and a survey questionnaire procedure was employed in this study. After the factor analysis, three underlying dimensions were found when examining Tao residents’ perceptions of social and cultural impacts of tourism, and they were named: positive cultural effects, negative cultural effects, and negative social effects. -

Thought on Packing For

Thoughts on Packing In General Dress Code at School -The dress code at Taiwanese schools tends to be much less formal than the dress code at schools in the United States. Basic shirts and pants are normally fine. Remember, though, that in an effort to be polite, others may tell you that it is okay to wear things that it really isn't okay to wear. So it's best to be a bit conservative at first until you see what others are wearing at your school. The key is to observe and communicate about expectations. -Remember to bring at least one pair of closed toed shoes. Any sandal that doesn't have an ankle strap is considered a slipper here. Even if you paid a great deal of money for them, if they don't have an ankle strap, they're slippers. Generally, flip-flops are not appropriate for school. -You can dress casually at school, but there are a few limitations on how casual you can dress. Skirts should be knee length (this is a general rule at most schools; perhaps talk with your co-teacher(s) and observe the way other teachers dress at your school). Shirts should not be revealing and long enough so that when you write on the board you won't expose too much. -Especially when teaching the younger grades, you will probably move around a lot and will likely end up dancing and making lots of dramatic gestures, so its important to wear a shirt long enough for all of this activity. -

Social Policies and Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan

Faculty of Social Sciences University of Helsinki Finland SOCIAL POLICIES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN TAIWAN ELDERLY CARE AMONG THE TAYAL I-An Gao (Wasiq Silan) DOCTORAL THESIS To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in lecture room 302, Athena, on 18 May 2021, at 8 R¶FORFN. Helsinki 2021 Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 186 (2021) ISSN 2343-273X (print) ISSN 2343-2748 (online) © I-An Gao (Wasiq Silan) Cover design and visualization: Pei-Yu Lin Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] ISBN 978-951-51-7005-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-7006-4 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2021 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how Taiwanese social policy deals with Indigenous peoples in caring for Tayal elderly. By delineating care for the elderly both in policy and practice, the study examines how relationships between indigeneity and coloniality are realized in today’s multicultural Taiwan. Decolonial scholars have argued that greater recognition of Indigenous rights is not the end of Indigenous peoples’ struggles. Social policy has much to learn from encountering its colonial past, in particular its links to colonization and assimilation. Meanwhile, coloniality continues to make the Indigenous perspective invisible, and imperialism continues to frame Indigenous peoples’ contemporary experience in how policies are constructed. This research focuses on tensions between state recognition and Indigenous peoples’ -

Healthy Cities in Taiwan

Healthy Cities in Taiwan Content 1. Development of healthy cities in Taiwan 2 2. Promotional models for healthy cities in Taiwan 3 3. Taiwan healthy city indicators 3 4. Taiwan healthy cities network 5 5. Taiwan Healthy City A wards 6 Appendix 13 I. Themes of Awards and Awardees for the First Taiwan Healthy City Award II. Themes of Awards and Awardees for the Second Taiwan Healthy City Award III. \Contact information and websites of healthy cities in Taiwan Commission: Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Taiwan Compile and Print: Healthy City Research Center, National Cheng Kung University October 2010 1. Development of healthy cities in Taiwan The healthy cities movement began in 1986. It was first promoted by the WHO Regional Office for Europe, and primarily targeted European cities. After almost two decades of work, the results have been very good, and European healthy cities are now exemplars for the world. As a result, WHO regional offices have started to advocate healthy cities for each of their regions. In Taiwan, the Republic of China decided to participate in the healthy cities movement in the beginning of the new Millennium. The Bureau of Health Promotion (BHP), Department of Health called for a pilot proposal in 2003, a cross-disciplinary team of scholars at National Cheng Kung University won the project, and found collaboration from Tainan City, thus, pioneered the healthy city development in Taiwan. BHP has since continued to fund other local authorities to promote healthy cities, including Miaoli County, Hualien County, Kaohsiung City and Taipei County. Since the results have been excellent, some other counties and cities have also allotted budgets to commission related departments for implementation. -

Atmospheric PM2.5 and Polychlorinated Dibenzo-P-Dioxins and Dibenzofurans in Taiwan

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 18: 762–779, 2018 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2018.02.0050 Atmospheric PM2.5 and Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxins and Dibenzofurans in Taiwan Yen-Yi Lee 1, Lin-Chi Wang2*, Jinning Zhu 3**, Jhong-Lin Wu4***, Kuan-Lin Lee1 1 Department of Environmental Engineering, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan 2 Department of Civil Engineering and Geomatics, Cheng Shiu University, Kaohsiung 83347, Taiwan 3 School of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei 246011, China 4 Sustainable Environment Research Laboratories, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan ABSTRACT In this study, the atmospheric PM2.5, increases/decreases of the PM2.5, the PM2.5/PM10 ratio, total PCDD/Fs-TEQ concentrations, PM2.5-bound total PCDD/Fs-TEQ content, and PCDD/F gas-particle partition in Taiwan were investigated for the period 2013 to 2017. In Taiwan, the annual average PM2.5 concentrations were found to be 28.9, 24.1, 21.4, 20.2, –3 and 19.9 µg m in 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017, respectively, which indicated that the annual variations in PM2.5 levels were decreasing during the study period. The average increases (+)/decreases (–) of PM2.5 concentrations were –16.7%, –11.1%, –5.75%, and –1.73% from 2013 to 2014, from 2014 to 2015, from 2015 to 2016, and from 2016 to 2017, respectively. Based to the relationship between PM10 values and total PCDD/F concentrations obtained from previous studies, we estimated that in 2017, the annual average total PCDD/Fs-TEQ concentrations ranged between 0.0148 –3 –3 (Lienchiang County) and 0.0573 pg WHO2005-TEQ m (Keelung City), and averaged 0.0296 pg WHO2005-TEQ m , while –1 the PM2.5-bound total PCDD/Fs-TEQ content ranged from 0.302 (Kaohsiung City) to 0.911 ng WHO2005-TEQ g –1 (Keelung City), at an average of 0.572 ng WHO2005-TEQ g . -

Chi-Chi, Taiwan Earthquake Event Report

TM Event Report Chi-Chi, Taiwan Earthquake .8E 7km depth N 120 23.8 6 M7. m. a. 47 1: 99 19 , 1 2 r e b m e t p e S Chi-Chi Reconnaissance Team Weimin Dong, Ph.D. Laurie Johnson, AICP RMS Team Leader, Earthquake Engineer RMS Event Response Coordinator, Urban Planner Guy Morrow, S.E. Craig Van Anne, M.S. RMS, Structural Engineer OYO RMS, Fire Protection Engineer Akio Tanaka Shukyo Segawa OYO RMS, Geophysicist OYO Corporation, Geophysicist Hideo Kagawa Chin-Hsun Yeh, Ph.D. Engineering & Risk Services, National Center for Research in Earthquake Structural Engineer Engineering, Associate Research Fellow Lun-Chang Chou, Ph.D. Kuo-Liang Wen, Ph.D. National Science and Technology Program for National Science and Technology Program for Hazards Mitigation, National Taiwan University Hazards Mitigation, National Taiwan University Yi-Ben Tsai, Ph.D. Wei-ling Chiang, Ph.D. National Central University, Professor National Central University, Professor Wenko Hsu Institute for Information Industry, Engineer, Special Systems Division The reconnaissance team members arrived in Taiwan on Wednesday, September 23, two days after the earthquake, and initially spent 20 man-days in the field. OYO RMS, OYO, and ERS reconnaissance team members jointly presented preliminary findings at a seminar in Tokyo on October 11. RMS joined Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) and members of the Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering (TCLEE) on October 10 in a week-long mission to further investigate power disruption and associated business interruption impacts, and collect additional loss data. Many of the team members, particularly our Taiwanese colleagues, have continued investigations of this earthquake. -

Indigenous Rights and Wildlife Conservation: the Vernacularization of International Law on Taiwan

Indigenous Rights and Wildlife Conservation: The Vernacularization of International Law on Taiwan Scott Simon Professeur École d’études sociologiques et anthropologiques Université d'Ottawa Awi Mona, Chih-Wei Tsai Associate Professor Department of Educational Management National Taipei University of Education Abstract Indigenous rights and wildlife conservation laws have become two important arenas for legal pluralism in Taiwan. In a process of vernacularization, Taiwan has adopted international legal norms in indigenous rights and wildlife conservation. Local actors from legislators to conservation officers and indigenous hunters refer not only to international and state law but also to indigenous customary law and other cultural norms in their interactions. In Seediq and Truku communities, the customary law of Gaya continues to inform the ways in which local hunters and trappers manage natural resources according to their own legal norms. There are, however, different individual interpretations of Gaya, and, in the absence of adequate legal protection, many hunting activities are clandestine and difficult to regulate. Fuller political autonomy, as envisioned in both the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Taiwan’s 2005 Basic Law on Indigenous Peoples, is needed in order that indigenous peoples can construct and manage their own institutions for common resource management. This 台灣人權學刊 第三卷第一期 2015 年 6 月 頁 3~31 3 台灣人權學刊 第三卷第一期 approach bodes best for both the realization of indigenous rights and effective wildlife conservation. Keywords indigenous rights, wildlife conservation, legal pluralism, hunting, Seediq, Truku, Taiwan The Republic of China (ROC), which lost the right to represent China in the United Nations (UN) in 1971, has systematically tried to keep up with UN norms and adopt key elements of evolving international law in its sole remaining jurisdiction on Taiwan, despite the lack of enforcement mechanisms and higher transaction costs to share relevant information and best practices.