King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution and Diversity Assessment of the Marine Macroalgae at Four Southern Districts of Tamil Nadu, India

Distribution and diversity assessment of the marine macroalgae at four southern districts of Tamil Nadu, India K. Sahayaraj1,*, S. Rajesh1, A. Asha1, J. M. Rathi2 & Patric Raja3 1Crop Protection Research Centre, Department of Advanced Zoology and Biotechnology, St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Palayamkottai – 627 002, Tamil Nadu, India, 2 Department of Chemistry, St. Mary’s College, Thoothukudi – 628 001, Tamil Nadu, India 3Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology, St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Palayamkottai – 627 002, Tamil Nadu, India *[Email: [email protected]] Received ; revised Present paper consists study on macroalgae seaweeds from Southern districts of Tamil Nadu viz., Kanyakumari, Tirunelveli, Tuticorin and Ramanathapuram. In total 57 taxa belonging to 37 genera representing Chlorophyta (18 taxa), Ochrophyta (14 taxa) and Rhodophyta (25 taxa) were recorded from 19 sampling sites during our study period (June 2009 to June 2010). Species wise, higher number of algae was recorded from Idinthakarai (84.21%). Gracilaria corticata has been distributed in 10 localities (= 52.63%). Among various localities, maximum (59%) and minimum (1%) species were recorded from Idinthakarai (Tirunelveli district) and Keelvaipaar (Tuticorin), respectively which situated in Bay of Bengal. Higher number of algae was recorded from the Bay of Bengal (67.7%) followed by Indian Ocean (25%) and Arabian Sea coasts (8%). Caulerpa cupressoides, Caulerpa veravalensis, Chaetomorpha crassa, Galoxaura marginata, Hormophysa triquetra and Spyridia asperum were recorded for first time from Tamil Nadu. This study contributes to the inshore marine macroalgae knowledge of these four coastal districts situated in Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea coasts and Bay of Bengal. [Keywords: Seaweeds – Distribution - Peninsular Indian coast] *Author for correspondence 1 Introduction Macroscopic marine algae, popularly known as seaweeds, constitute one of the important living resources of the ocean. -

The Complicated Identities and the Complex Negotiations of Catholics and Hindus in South India

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 17 Article 7 January 2004 Dialogue 'On The Ground': The Complicated Identities and the Complex Negotiations of Catholics and Hindus in South India Selva J. Raj Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Raj, Selva J. (2004) "Dialogue 'On The Ground': The Complicated Identities and the Complex Negotiations of Catholics and Hindus in South India," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 17, Article 7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1316 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Raj: Dialogue 'On The Ground': The Complicated Identities and the Complex Negotiations of Catholics and Hindus in South India Dialogue 'On The Ground': The Complicated Identities and the Complex Negotiations of Catholics and Hindus in South India l Selva J. Raj Albion College INTERRELIGIOUS dialogue is a vital 'dialogue on the ground,' delineates the theological concem for the Catholic Church social and religious themes embedded in this in India:. Over the past three decades, church ritual, and reflects on its implications for leaders (Amalorpavadoss 1978), progressive interreligious dialogue. theologians (Amaladoss 1979), and maverick monastics (Griffiths 1982) have The Shrine, The Saint, and the experimented with various models and Devotees forms of interreligious dialogue. Quite distinct from these contrived institutional A. -

Tirunelveli District

CLASSIFY THE TOTAL NO OF VULNERABLE LOCATIONS IN THE FOLLOWING CATEGORY TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT Highly Moderately Less Total No.of Sl. No. Taluk Vulnerable Vulnerable Vulnerable Vulnerable Vulnearable Location 1 Tirunelveli - - 1 6 7 2 Palayamkottai - 6 9 9 24 3 Manur - - - - 0 4 Sankarankovil - 3 - - 3 5 Tenkasi - - 2 - 2 6 Kadayanallur - 1 - - 1 7 Tiruvenkadam - - - 4 4 8 Shencottai - 3 - - 3 9 Alangulam - - 1 5 6 10 Veerakeralampudur - 5 2 - 7 11 Sivagiri - - 4 2 6 12 Ambasamudram - 3 2 6 11 13 Cheranmahadevi - 1 1 - 2 14 Nanguneri - - - 4 4 15 Radhapuram 11 22 2 10 45 Grand Total 11 44 24 46 125 District :TIRUNELVELI Highly Vulnerable Type of Local Body (Village Panchayat/Town S.No Name of the Location Name of the Local Body Panchayat/ Municipalities and Corporation) 1 Kannanallur Kannanallur(V) Kannanallur(Panchayat) 2 Chithur Kannanallur(V) Kannanallur(Panchayat) 3 Chinnammalpuram Anaikulam(V) Anaikulam Panchayat 4 Thulukarpatti Anaikulam(V) Anaikulam Panchayat 5 Thalavarmani Anaikulam(V) Anaikulam Panchayat 6 Mailaputhur Melur Anaikulam(V) Anaikulam Panchayat 7 Mailaputhur Keezhoor Anaikulam(V) Anaikulam Panchayat 8 Kovankulam Kovankulam(V) Kovankulam Panchayat Kovaneri,Kumaraputhurkudieruppu, 9 Vadakuvallioor Part I Vadakkuvallioor Town Panchayat Kottaiyadi 10 Main Road - Vallioor Vadakuvallioor Part I Vadakkuvallioor Town Panchayat 11 Nambiyar vilai Vadakuvallioor Part I Vadakkuvallioor Town Panchayat Vulnerable Type of Local Body (Village Panchayat/Town S.No Name of the Location Name of the Local Body Panchayat/ Municipalities -

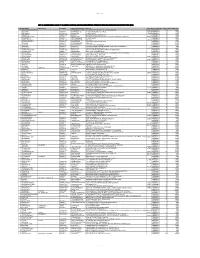

Sl. NO. Name of the Guide Name of the Research Scholar Reg.No Title Year of Registration Discipline 1. Dr.V.Rilbert Janarthanan

Sl. Year of Name of the Guide Name of the Research Scholar Reg.No Title Discipline NO. registration Dr.V.Rilbert Janarthanan Mr.K.Ganesa Moorthy Gjpdz; fPo;f;fzf;F Asst.Prof of Tamil 103D,North Street 1. 11001 Ey;fSk; r*fg; gz;ghl;L 29-10-2013 Tamil St.Xaviers College Arugankulam(po),Sivagiri(tk) khw;Wk; gjpTfSk; Tirunelveli Tirunelveli-627757 Dr.A.Ramasamy Ms.P.Natchiar Prof & HOD of Tamil 22M.K Srteet vallam(po) 11002 vLj;Jiug;gpay; 2. M.S.University 30-10-2013 Tamil Ilangi Tenkasi(tk) (Cancelled) Nehf;fpd; rpyg;gjpf;fhuk; Tvl Tvl-627809 627012 Dr.S.Senthilnathan Mr.E.Edwin Effect of plant extracts and its Bio-Technology Asst.Prof 3. Moonkilvillai Kalpady(po) 11003 active compound against 30-10-2013 Zoology SPKCES M.S.University Kanyakumari-629204 stored grain pest (inter disciplinary) Alwarkurichi Tvl-627412 Dr.S.Senthilnathan Effect of medicinal plant and Mr.P.Vasantha Srinivasan Bio-Medical genetics Asst.Prof entomopatho generic fungi on 4. 11/88 B5 Anjanaya Nagar 11004 30-10-2013 Zoology SPKCES M.S.University the immune response of Suchindram K.K(dist)-629704 (inter disciplinary) Alwarkurichi Tvl-627412 Eepidopternam Larrae Ms.S.Maheshwari Dr.P.Arockia Jansi Rani Recognition of human 1A/18 Bryant Nagar,5th middle Computer Science and 5. Asst.Prof,Dept of CSE 11005 activities from video using 18-11-2013 street Tuticorin Engineering classificaition methods MS University 628008 Dr.P.Arockia Jansi Rani P.Mohamed Fathimal Visual Cryptography Computer Science and 6. Asst.Prof,Dept of CSE 70,MGP sannathi street pettai 11006 20-11-2013 Algorithm for image sharing Engineering MS University Tvl-627004 J.Kavitha Dr.P.Arockia Jansi Rani 2/9 vellakoil suganthalai (po) Combination of Structure and Computer Science and 7. -

62 DOI:1 0 .2 6 5 2 4 / K Rj1

Kong. Res. J. 3(2) : 62-66, 2016 ISSN 2349-2694 6 Kongunadu Arts and Science College, Coimbatore. A SURVEY OF ISOETES COROMANDELINA L. F. POPULATIONS IN TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT Sahaya Anthony Xavier, G*., S. Sundhari, P. Mariammal, M. Vaishnavi and T. Vanitha Department of Botany, St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Palayamkottai – 627002. *E.mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT DOI:10.26524/krj14 The genus Isoetes is a cosmopolitan genus found around the world. The genus consists of aquatic or semi-aquatic plants needing water for survival. The distribution of Isoetes coromandelina L. f. in the freshwater ponds of Tirunelveli district was studied. The results of the survey show that the population of Isoetes coromandelina in Tirunelveli district are healthy and flourish wherever non-polluted, nutrient poor waters are available. Although there is no danger to the populations of Isoetes at present, water pollution could endanger the survival of the species. Keywords: Isoetes coromandelina, survey, Tirunelveli, cosmopolitan genus. depend on the water released from the dams. When 1. INTRODUCTION the north-east monsoon fails, the ponds in the Isoetes L. is a cosmopolitan genus of eastern parts of the district have been observed to be heterosporous lycopsids comprising approximately dry and without water for years together. 150 species found in lakes, wetlands (swamps, Though Isoetes cannot live without water, it marshes), and terrestrial habitats (Taylor et al., has been observed to regrow vigorously once water 1993) all over the world. 16 species of Isoetes have is made available either through rain or by release been reported from different geographical regions of from the dam. -

AND IT's CONTACT NUMBER Tirunelveli 0462

IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS AND EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTRE (EOC) AND IT’S CONTACT NUMBER Name of the Office Office No. Collector’s Office Control Room 0462-2501032-35 Collector’s Office Toll Free No. 1077 Revenue Divisional Officer, Tirunelveli 0462-2501333 Revenue Divisional Officer, Cheranmahadevi 04634-260124 Tirunelveli 0462 – 2333169 Manur 0462 - 2485100 Palayamkottai 0462 - 2500086 Cheranmahadevi 04634 - 260007 Ambasamudram 04634- 250348 Nanguneri 04635 - 250123 Radhapuram 04637 – 254122 Tisaiyanvilai 04637 – 271001 1 TALUK TAHSILDAR Taluk Tahsildars Office No. Residence No. Mobile No. Tirunelveli 0462-2333169 9047623095 9445000671 Manoor 0462-2485100 - 9865667952 Palayamkottai 0462-2500086 - 9445000669 Ambasamudram 04634-250348 04634-250313 9445000672 Cheranmahadevi 04634-260007 - 9486428089 Nanguneri 04635-250123 04635-250132 9445000673 Radhapuram 04637-254122 04637-254140 9445000674 Tisaiyanvilai 04637-271001 - 9442949407 2 jpUney;Ntyp khtl;lj;jpy; cs;s midj;J tl;lhl;rpah; mYtyfq;fspd; rpwg;G nray;ghl;L ikaq;fspd; njhiyNgrp vz;fs; kw;Wk; ,izatop njhiyNgrp vz;fs; tpguk; fPo;f;fz;lthW ngwg;gl;Ls;sJ. Sl. Mobile No. with Details Land Line No No. Whatsapp facility 0462 - 2501070 6374001902 District EOC 0462 – 2501012 6374013254 Toll Free No 1077 1 Tirunelveli 0462 – 2333169 9944871001 2 Manur 0462 - 2485100 9442329061 3 Palayamkottai 0462 - 2501469 6381527044 4 Cheranmahadevi 04634 - 260007 9597840056 5 Ambasamudram 04634- 250348 9442907935 6 Nanguneri 04635 - 250123 8248774300 7 Radhapuram 04637 – 254122 9444042534 8 Tisaiyanvilai 04637 – 271001 9940226725 3 K¡»a Jiw¤ jiyt®fë‹ bršngh‹ v§fŸ mYtyf vz; 1. kht£l M£Á¤ jiyt®, ÂUbešntè 9444185000 2. kht£l tUthŒ mYty®, ÂUbešntè 9445000928 3. khefu fhtš Miza®, ÂUbešntè 9498199499 0462-2970160 4. kht£l fhtš f§fhâ¥ghs®, ÂUbešntè 9445914411 0462-2568025 5. -

Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission Bulletin

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN-466/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 196/2009 2015 [Price: Rs. 280.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION BULLETIN No. 18] CHENNAI, SUNDAY, AUGUST 16, 2015 Aadi 31, Manmadha, Thiruvalluvar Aandu-2046 CONTENTS DEPARTMENTAL TESTS—RESULTS, MAY 2015 Name of the Tests and Code Numbers Pages. Pages. Second Class Language Test (Full Test) Part ‘A’ The Tamil Nadu Wakf Board Department Test First Written Examination and Viva Voce Parts ‘B’ ‘C’ Paper Detailed Application (With Books) (Test 2425-2434 and ‘D’ (Test Code No. 001) .. .. .. Code No. 113) .. .. .. .. 2661 Second Class Language Test Part ‘D’ only Viva Departmental Test in the Manual of the Firemanship Voce (Test Code No. 209) .. .. .. 2434-2435 for Officers of the Tamil Nadu Fire Service First Paper & Second Paper (Without Books) Third Class Language Test - Hindi (Viva Voce) (Test Code No. 008 & 021) .. .. .. (Test Code 210), Kannada (Viva Voce) 2661 (Test Code 211), Malayalam (Viva Voce) (Test The Agricultural Department Test for Members of Code 212), Tamil (Viva Voce) (Test Code 213), the Tamil Nadu Ministerial Service in the Telegu (Viva Voce) (Test Code 214), Urdu (Viva Agriculture Department (With Books) Test Voce) (Test Code 215) .. .. .. 2435-2436 Code No. 197) .. .. .. .. 2662-2664 The Account Test for Subordinate Officers - Panchayat Development Account Test (With Part-I (With Books) (Test Code No. 176) .. 2437-2592 Books) (Test Code No. 202).. .. .. 2664-2673 The Account Test for Subordinate Officers The Agricultural Department Test for the Technical Part II (With Books) (Test Code No. 190) .. 2593-2626 Officers of the Agriculture Department Departmental Test for Rural Welfare Officer (With Books) (Test Code No. -

Unpaid Data 1

Unpaid_Data_1 LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS LIABLE TO TRANSFER OF UNPAID AND UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND DIVIDEND TO INVESTOR EDUCATION PROTECTION FUND (IEPF) S.No First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband Name Address PINCodeFolio NumberNo of SharesAmount Due(in Rs.) 1 RADHAKRISHNANTSSSD SRITSSSDURAISAMY CO-OPERATIVE STORES LTD., VIRUDHUNAGAR 626001 P00000011 15 13500 2 MUTHIAH NADAR M SRIMARIMUTHU THIRUTHANGAL SATTUR TALUK 626130 P00000014 2 1800 3 SHUNMUGA NADAR GAS SRISUBBIAH THOOTHUKUDI 628001 P00000015 11 9900 4 KALIAPPA NADAR NAA SRIAIYA ELAYIRAMPANNAI, SATTUR VIA P00000023 2 1800 5 SANKARALINGAM NADAR A SRIARUMUGA C/O SRI.S.S.M.MAYANDI NADAR, 24-KALMANDAPAM ROAD, CHENNAI 600013 P00000024 2 1800 6 GANAPATHY NADAR P SRIPERIAKUMAR THOOTHUKUDI P00000046 10 9000 7 SANKARALINGA NADAR ASS SRICHONAMUTHU SIVAKASI 626123 P00000050 1 900 8 SHUNMUGAVELU NADAR VS SRIVSUBBIAH 357-MOGUL STREET, RANGOON P00000084 11 9900 9 VELLIAH NADAR S SRIVSWAMIDASS RANGOON P00000090 3 2700 10 THAVASI NADAR KP SRIKPERIANNA 40-28TH STREET, RANGOON P00000091 2 1800 11 DAWSON NADAR A NAPPAVOO C/O SRI.N.SAMUEL, PRASER STREET, POST OFFICE, RANGOON-1 P00000095 1 900 12 THIRUVADI NADAR R RAMALINGA KALKURICHI, ARUPPUKOTTAI 626101 P00000096 10 9000 13 KARUPPANASAMY NADAR ALM MAHALINGA KASI VISWANATHAN NORTH STREET, KUMBAKONAM P00000097 10 9000 14 PADMAVATHI ALBERT SRIPEALBERT EAST GATE, SAWYERPURAM P00000101 40 36000 15 KANAPATHY NADAR TKAA TKAANNAMALAI C/O SRI.N.S.S.CHINNASAMY NADAR, CHITRAKARA VEEDHI, MADURAI P00000105 5 4500 16 MUTHUCHAMY NADAR PR PRAJAKUMARU EAST MASI STREET, MADURAI P00000107 10 9000 17 CHIDAMBARA NADAR M VMARIAPPA 207-B EAST MARRET STREET, MADURAI 625001 P00000108 5 4500 18 KARUPPIAH NADAR KKM LATE SRIKKMUTHU EMANESWARAM, PARAMAKUDI T.K. -

Significance of the Appellation Korkai and Its Language: the Deformation and Segregation of Parathavar Community from the British Reign to Modern Era

====================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:4 April 2019 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ===================================================================== Significance of the Appellation Korkai and Its Language: The Deformation And Segregation of Parathavar Community from the British Reign to Modern Era V. Suganya Dr. B. Padmanabhan M.Phil. Research Scholar Assistant Professor Dept. of English and Foreign Languages Dept. of English and Foreign Languages Bharathiar University Bharathiar University Coimbatore Coimbatore Abstract Korkai is a novel exclusively written on the fishermen community of Tuticorin district, Tamil Nadu. The author R.N. Joe D’Cruz has tried to exhibit the annihilation of Parathavar community people’s fame and sea business. During the Kings’ era, people of every community had their own exclusive businesses, values and principles. Likewise, Parathavar community people have been playing a prominent role in Tuticorin district to enhance sea businesses since the Pandiyan reign. Now, their life has become a history to others and mystery to them. The novel Korkai is written to find the reason behind their trauma and lifelong segregation from the others and it also opens out the life history of the Parathavar community. Thus, the paper delves to explore the narrative techniques, analyse the major characters, themes, the language, Nellai Tamil, of the novel Korkai, fishermen’s depravity, jealousy and greed among them and also the modern equipments used in sailing which have lead to the eradication of their fame, business, values and principles in modern era. Keywords: R.N. Joe D’Cruz, Korkai, Fishermen, Parathavar community, Pandiyan Kingdom, Nellai Tamil and depravity. -

Tirunelveli District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR ROUGH STONE TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT 2019 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT-TIRUNELVELI 1 1. INTRODUCTION In conjunction to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the Government of India Notification No.SO 3611 (E) dated 25.07.2018 and SO 190 (E) dated 20.01.2016 the District Level Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) and District Environment Appraisal Committee (DEAC) were constituted in Tirunelveli District for the grant of Environmental Clearance for category “B2” projects for quarrying of Minor Minerals. The main purpose of preparation of District Survey Report is to identify the mineral resources and develop the mining activities along with relevant current geological data of the District. The DEAC will scrutinize and screen scope of the category “B2” projects and the DEIAA will grant Environmental Clearance based on the recommendations of the DEAC for the Minor Minerals on the basis of District Survey Report. This District Mineral Survey Report is prepared on the basis of field work carried out in Tirunelveli district by the official from Geological Survey of India and Directorate of Geology and Mining, (Tirunelveli District), Govt. of Tamilnadu. Tirunelveli district was formed in the year 1790 and is one of the oldest districts in the state, with effect from 20.10.1986 the district was bifurcated and new district Thothukudi was formed carving it. Tirunelveli district has geographical area of 6759 sq.km and lies in the south eastern part of Tamilnadu state. The district is bounded by the coordinates 08°05 to 09°30’ N and 77°05’ to 78°25 E and shares boundary with Virudunagar district in north, Thothukudi district in east, Kanniyakumari district in south and with Kerala state in the West. -

Performance Analysis of Fisherwomen Self Help Groups in Tamil Nadu

PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS OF FISHERWOMEN SELF HELP GROUPS IN TAMILNADU FINAL RERPORT SUBMITTED TO NATIONAL BANK FOR AGRICULTURAL AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR Dr.R.JAYARAMAN , M.F.Sc, Ph.D DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES RESOURCES & ECONOMICS FISHERIES COLLEGE AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE TAMIL NADU VETERINARY AND ANIMAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY THOOTHUKKUDI – 628 008 2005 ABBREVIATIONS AWED Association for Women Education and Development BWDA Bullock - cart Women Development Association BPL Below Poverty Line CMG Credit Management Groups EA Economic Activity FIs F inancial Institutions IEC Information Education and Communication IOB Indian Overseas Bank MFI Microfinance Institutions Mfi Microfinance insurance MFO Microfinance Organization NABARD National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development NBFCs N on-Banking Financial Corporations NGO Non Government Organization PRI Panchayat Raj Institution PLF Panchayat Level Federation PGB Pandyan Grama Bank RRB Regional Rural Bank RBI Reserve Bank of India RFA Revolving Fund Assistance SFDA Small Farmers Development Agency SGSY Swarnajayanthi Gram Swarojar Yojana SHGs Self Help Groups SIDBI Small Industrial Development Bank of India TMSSS Thoothukudi Multipurpose Social Service Society MFDF Microfinance Development Fund IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development CONTENTS Chapter Topic Page No. No. 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. DESIGN OF THE STUDY 8 3. SOCIO- ECONOMIC PROFILE OF FISHERWOMEN 10 4. SAVINGS, LOAN PRODUCTS AND MICROCREDIT 14 TO FISHERWOMEN 5. IMPACTS OF THE MICROCREDIT PROGRAMME 21 6. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2015 [Price: Rs. 5.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 56] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, MARCH 13, 2015 Maasi 29, Jaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2046 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT HIGHWAYS AND MINOR PORTS NOTICE DEPARTMENT Under sub-section (1) of Section 15 of the [G.O. (D) No. 61, Highways and Minor Ports (HN2), Tamil Nadu Highways Act, 2001 (Tamil Nadu 13th March 2015, ñ£C 29, üò, F¼õœÀõ˜ Act 34 of 2002), the Governor of Tamil Nadu hereby .] ݇´-2046 acquires the lands specified in the Schedule below and measuring to an extent of 64337 Square metres No. II(2)/HWMP/132(b)/2015. a specified in the Schedule below a little more or The Governor of Tamil Nadu having been less required for Highways Purpose to wit for satisfied that the lands specifies in the Schedule Upgrading the State Highways Road (SH-89) below are required for Highways Purpose to wit for Nanguneri – Uvari Road from kilometre 0.000 to upgrading the State Highways Road (SH-89) kilometre 35.200 in Therkku Nanguneri and some Nanguneri - Uvari Road from Kilometre 0.000 to Villages in Nanguneri and Radhapuram Taluks, Kilometre 35.200 in Therkku Nanguneri and some Tirunelveli District. Villages in Nanguneri and Radhapuram Taluk, Tirunelveli District and it having already been decided The plan of the lands is under acquisition kept in that the entire amount