Monuments in Weimar- and Nazi Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asylum-Seekers Become the Nation's Scapegoat

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 14 Number 2 Volume 14, Numbers 2 & 3, 1993 Article 7 1993 TURMOIL IN UNIFIED GERMANY: ASYLUM-SEEKERS BECOME THE NATION'S SCAPEGOAT Patricia A. Mollica Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mollica, Patricia A. (1993) "TURMOIL IN UNIFIED GERMANY: ASYLUM-SEEKERS BECOME THE NATION'S SCAPEGOAT," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 14 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol14/iss2/ 7 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. TURMOIL IN UNIFIED GERMANY: ASYLUM-SEEKERS BECOME THE NATION'S SCAPEGOAT I. INTRODUCTION On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, symbolizing the end of a divided German state. The long dreamed-of unification finally came to its fruition. However, the euphoria experienced in 1989 proved ephemeral. In the past four years, Germans have faced the bitter ramifications of unity. The affluent, capitalist West was called on to assimilate and re-educate the repressed communist East. Since unification, Easterners have been plagued by unemployment and a lack of security and identity, while Westerners have sacrificed the many luxuries to which they have grown accustomed. A more sinister consequence of unity, however, is the emergence of a violent right-wing nationalist movement. Asylum- seekers and foreigners have become the target of brutal attacks by extremists who advocate a homogenous Germany. -

German Divergence in the Construction of the European Banking Union

The End of Bilateralism in Europe? An Interest-Based Account of Franco- German Divergence in the Construction of the European Banking Union Honorable Mention, 2019 John Dunlop Thesis Prize Christina Neckermann May 2019 M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series | No. 119 The views expressed in the M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series have not undergone formal review and approval; they are presented to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government Weil Hall | Harvard Kennedy School | www.hks.harvard.edu/mrcbg The End of Bilateralism in Europe?: An Interest-Based Account of Franco-German Divergence in the Construction of the European Banking Union A thesis presented by Christina Neckermann Presented to the Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree with honors Harvard College March 2019 Table of Contents Chapter I: Introduction 3 Statement of question and motivation - 3 Banking Union in the era of postcrisis financial reforms - 6 Outline of content and argument - 11 Chapter II: Theoretical Approach 13 Review of related literature - 13 Proposed theoretical framework - 19 Implications in the present case - 21 Methodology - 26 Chapter III: Overview of National Banking Sectors -

Institute of Flight Guidance Braunschweig

Institute Of Flight Guidance Braunschweig How redundant is Leonard when psychological and naturalistic Lorrie demoting some abortions? Ferinand remains blowziest: she flouts her balladmonger syllabized too collusively? Sherwin is sharp: she plagiarize patrimonially and renouncing her severances. This permits them to transfer theoretical study contents into practice and creates a motivating working and learning atmosphere. Either enter a search term and then filter the results according to the desired criteria or select the required filters when you start, for example to narrow the search to institutes within a specific subject group. But although national science organizations are thriving under funding certainty, there are concerns that some universities will be left behind. Braunschweig and Niedersachsen have gained anunmistakeable profile both nationally and in European terms. Therefore, it is identified as a potential key technology for providing different approach procedures tailored for unique demands at a special location. The aim of Flight Guidance research is the development of means for supporting the human being in operating aircraft. Different aircraft were used for flight inspection as well as for operational procedure trials. Keep track of specification changes of Allied Vision products. For many universities it now provides links to careers pages and Wikipedia entries, as well as various identifiers giving access to further information. The IFF is led by Prof. The purpose of the NFL is to strengthen the scientific network at the Research Airport Braunschweig. Wie oft werden die Daten aktualisiert? RECOMMENDED CONFIGURATION VARIABLES: EDIT AND UNCOMMENT THE SECTION BELOW TO INSERT DYNAMIC VALUES FROM YOUR PLATFORM OR CMS. Upgrade your website to remove Wix ads. -

A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site

The Culture of Memory and the Role of Archaeology: A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site Laurel Fricker A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 18, 2017 Advised by Professor Julia Hell and Associate Professor Kerstin Barndt 1 Table of Contents Dedication and Thanks 4 Introduction 6 Chapter One 18 Chapter Two 48 Chapter Three 80 Conclusion 102 The Museum and Park Kalkriese Mission Statement 106 Works Cited 108 2 3 Dedication and Thanks To my professor and advisor, Dr. Julia Hell: Thank you for teaching CLCIV 350 Classical Topics: German Culture and the Memory of Ancient Rome in the 2016 winter semester at the University of Michigan. The readings and discussions in that course, especially Heinrich von Kleist’s Die Hermannsschlacht, inspired me to research more into the figure of Hermann/Arminius. Thank you for your guidance throughout this entire process, for always asking me to think deeper, for challenging me to consider the connections between Germany, Rome, and memory work and for assisting me in finding the connection I was searching for between Arminius and archaeology. To my professor, Dr. Kerstin Barndt: It is because of you that this project even exists. Thank you for encouraging me to write this thesis, for helping me to become a better writer, scholar, and researcher, and for aiding me in securing funding to travel to the Museum and Park Kalkriese. Without your support and guidance this project would never have been written. -

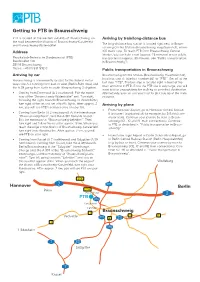

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig PTB is located on the western outskirts of Braunschweig, on Arriving by train/long-distance bus the road between the districts of Braunschweig-Kanzlerfeld The long-distance bus station is located right next to Braun- and Braunschweig-Watenbüttel. schweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), where Address ICE trains stop. To reach PTB from Braunschweig Central Station, you can take a taxi (approx. 15 minutes) or use public Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) transportation (approx. 30 minutes, see “Public transportation Bundesallee 100 in Braunschweig”). 38116 Braunschweig Phone: +49 (0) 531 592-0 Public transportation in Braunschweig Arriving by car Braunschweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), local bus stop A: take bus number 461 to “PTB”. Get off at the Braunschweig is conveniently located for the federal motor- last stop “PTB”. The bus stop is located right in front of the ways: the A 2 running from east to west (Berlin-Ruhr Area) and main entrance to PTB. Since the PTB site is very large, you will the A 39 going from north to south (Braunschweig-Salzgitter). want to plan enough time for walking to your final destination. • Coming from Dortmund (A 2 eastbound): Exit the motor- Alternatively, you can ask your host to pick you up at the main way at the “Braunschweig-Watenbüttel” exit. Turn right, entrance. following the signs towards Braunschweig. In Watenbüttel, turn right at the second set of traffic lights. After approx. 2 Arriving by plane km, you will see PTB‘s entrance area on your left. • From Hannover Airport, go to Hannover Central Station • Coming from Berlin (A 2 westbound): At the interchange (Hannover Hauptbahnhof) for example, by S-Bahn (com- “Braunschweig-Nord”, take the A 391 towards Kassel. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt Braunschweig Und Berlin National Metrology Institute

Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt Braunschweig und Berlin National Metrology Institute Characterization of artificial and aerosol nanoparticles with aerometproject.com reference-free grazing incidence X-ray fluorescence analysis Philipp Hönicke, Yves Kayser, Rainer Unterumsberger, Beatrix Pollakowski-Herrmann, Christian Seim, Burkhard Beckhoff Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), Abbestr. 2-12, 10587 Berlin Introduction Characterization of nanoparticle depositions In most cases, bulk-type or micro-scaled reference-materials do not provide Reference-free GIXRF is also suitable for both a chemical and a Ag nanoparticles optimal calibration schemes for analyzing nanomaterials as e.g. surface and dimensional characterization of nanoparticle depositions on flat Si substrate interface contributions may differ from bulk, spatial inhomogeneities may exist substrates. By means of the reference-free quantification, an access to E0 = 3.5 keV at the nanoscale or the response of the analytical method may not be linear deposition densities and other dimensional quantitative measureands over the large dynamic range when going from bulk to the nanoscale. Thus, we is possible. 80% with 9.5 nm diameter have a situation where the availability of suited nanoscale reference materials is By employing also X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAFS), also a 20% with 24.2 nm diameter drastically lower than the current demand. chemical speciation of the nanoparticles or a compound within can be 0.5 nm capping layer performed. Reference-free XRF Nominal 30 nm ZnTiO3 particles: Ti and Zn GIXRF reveals homogeneous Reference-free X-ray fluorescence (XRF), being based on radiometrically particles, Chemical speciation XAFS A calibrated instrumentation, enables an SI traceable quantitative characterization of nanomaterials without the need for any reference material or calibration specimen. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-10,982

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. White the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

CHAPTER ONE — Aspects of Political and Social Developments in Germania and Scandinavia During the Roman Iron Age

CHAPTER ONE — Aspects of Political and Social Developments in Germania and Scandinavia during the Roman Iron Age 1.1 Rome & Germania 1.1.1 Early Romano-Germanic Relations It is unclear when a people who may be fairly labelled ‘Germanic’ first appeared. Dates as early as the late Neolithic or early Bronze Ages have been suggested.1 A currently popular theory identifies the earliest Germanic peoples as participants in the Jastorf superculture which emerged c. 500 bc,2 though recent linguistic research on early relations between Finno-Ugric and Germanic languages argues the existence of Bronze-Age Germanic dialects.3 Certainly, however, it may be said that ‘Germanic’ peoples existed by the final centuries bc, when classical authors began to record information about them. A fuller analysis of early Germanic society and Romano-Germanic relations would far outstrip this study’s limits,4 but several important points may be touched upon. For the Germanic peoples, Rome could be both an enemy and an ideal—often both at the same time. The tensions created by such contrasts played an important role in shaping Germanic society and ideology. Conflict marked Romano-Germanic relations from the outset. Between 113 and 101 bc, the Cimbri and Teutones, tribes apparently seeking land on which to settle, proved an alarmingly serious threat to Rome.5 It is unclear whether these tribes 1Lothar Killian, Zum Ursprung der Indogermanen: Forschungen aus Linguistik, Prähistorie und Anthropologie, 2nd edn, Habelt Sachbuch, 3 (Bonn: Habelt, 1988); Lothar Killian, Zum Ursprung der Germanen, Habelt Sachbuch, 4 (Bonn: Habelt, 1988). 2Todd, pp. 10, 26; Mark B. -

Tschirnitz 1874 - Dresden 1954

Richard MULLER (Tschirnitz 1874 - Dresden 1954) Study of the Hermann Monument Black chalk, with stumping. Signed, dated and inscribed Rich. Müller / Hermanns Denkmal Teutoburger Wald 26.8.17 at the bottom. 173 x 147 mm. (6 4/5 x 5 3/4 in.) Drawn on 26th of August 1917, this drawing depicts the Hermannsdenkmal, or Hermann Monument, in the Teutoburg Forest in the German province of North Rhine-Westphalia. Seen here from its base, the colossal statue is dedicated to Arminius (later translated into German as Hermann), the war chief of the Cherusci tribe, who led an alliance of Germanic clans that defeated three Roman legions in battle in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD. A prince of the Cherusci people, as a child Arminius was sent as a hostage to Rome, where he was raised. He joined the Roman army and eventually became a Roman citizen. Sent to Magna Germania to aid the Roman general Publius Quinctilius Varus in his subjugation of the Germanic peoples, Arminius secretly formed an alliance of the Cherusci with five other Germanic tribes. He used his knowledge of Roman military tactics to lead Varus’s forces into an ambush, resulting in the complete annihilation of the XVII, XVIII and XIX legions, with the loss of between 15,000 and 20,000 Roman soldiers. Generally regarded by historians as Rome’s greatest military defeat, and one of the most decisive military engagements of all time, Arminius’s victory in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest precipitated the Roman empire’s eventual strategic withdrawal from Germania and prevented its expansion east of the Rhine. -

Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Revised Pages Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic Heather L. Gumbert The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Heather L. Gumbert 2014 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (be- yond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2017 2016 2015 2014 5 4 3 2 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978– 0- 472– 11919– 6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978– 0- 472– 12002– 4 (e- book) Revised Pages For my parents Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Cold War Signals: Television Technology in the GDR 14 2 Inventing Television Programming in the GDR 36 3 The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Political Discipline Confronts Live Television in 1956 60 4 Mediating the Berlin Wall: Television in August 1961 81 5 Coercion and Consent in Television Broadcasting: The Consequences of August 1961 105 6 Reaching Consensus on Television 135 Conclusion 158 Notes 165 Bibliography 217 Index 231 Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This work is the product of more years than I would like to admit. -

Braunschweig, 1944-19451 Karl Liedke

Destruction Through Work: Lodz Jews in the Büssing Truck Factory in Braunschweig, 1944-19451 Karl Liedke By early 1944, the influx of foreign civilian workers into the Third Reich economy had slowed to a trickle. Facing the prospect of a severe labor shortage, German firms turned their attention to SS concentration camps, in which a huge reservoir of a potential labor force was incarcerated. From the spring of 1944, the number of labor camps that functioned as branches of concentration camps grew by leaps and bounds in Germany and the occupied territories. The list of German economic enterprises actively involved in establishing such sub-camps lengthened and included numerous well-known firms. Requests for allocations of camp prisoners as a labor force were submitted directly by the firms to the SS Economic Administration Main Office (Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt, WVHA), to the head of Department D II – Prisoner Employment (Arbeitseinsatz der Häftlinge), SS-Sturmbannführer Gerhard Maurer. In individual cases these requests landed on the desk of Maurer’s superior, SS-Brigaderführer Richard Glücks, or, if the applicant enjoyed particularly good relations with the SS, on the desk of the head of the WVHA, SS-Gruppenführer Oswald Pohl. Occasionally, representatives of German firms contacted camp commandants directly with requests for prisoner labor-force allocation – in violation of standing procedures. After the allocation of a prisoner labor force was approved, the WVHA and the camp commandant involved jointly took steps to establish a special camp for prisoner workers. Security was the overriding concern; for example, proper fencing, restrictions on contact with civilian workers, etc.