Posljednji Prelom.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Route Planner Central Dalmatia Bases: Sibenik (Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac) Route 3 (1 Week)

Route planner Central Dalmatia bases: Sibenik (Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac) route 3 (1 week) DUGI OTOK Sali Biograd NP Telascica VRGADA Pirovac Piskera Murter Skradin KORNAT Vodice ZLARIN Sibenik KAKAN KAPRIJE ZIRJE Primosten day: destination from: to: 1 Saturday Biograd/ Vodice (possible bathing stops: Zlarin or MURTER Jezera/ TIJAT Tijascica) Pirovac/Sibenik 2 Sunday Vodice Skradin 3 Monday Skradin ZLARIN Zlarin or TIJAT Tijascica 4 Tuesday ZLARIN Zlarin or TIJAT KAPRIJE Kaprije or KAKAN Tijascica 5 Wednesday KAPRIJE/KAKAN ZIRJE Vela Stupica 6 Thursday ZIRJE Vela Stupica MURTER Vucigrade, Murter or VRGADA 7 Friday MURTER Vucigrade, Mur- Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac/Sibenik ter or VRGADA Page 1 Location descriptions Biograd Biograd the „white city“ or royal city is a modern city. For a long time, it has been the residence of medieval Croatian dynasties, whose splendor is still visible in the old town. During the day, life mainly takes place on the beaches and the harbor prome- nade, in the evening the bustle shifts to the promenade of the old town. Numerous shops, restaurants, cafes, bars and ice cream parlors await the tourists. Biograd is a popular port of departure in the heart of Dalmatia. The Pasman Canal and the islands of Pasman and Uglijan, as well as the beautiful world of the Kornati Islands are right on the doorstep. MURTER Jezera, Murter and the bays Murter is also called the gateway to the Kornati, but the peninsula itself has also a lot to offer. The starting port Jezera is a lovely little place with a nice beach, shops, restaurants and bars. -

Libertarian Marxism Mao-Spontex Open Marxism Popular Assembly Sovereign Citizen Movement Spontaneism Sui Iuris

Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis Brian Marks1 University of Arizona School of Geography and Development [email protected] Abstract Autonomist Marxism is a political tendency premised on the autonomy of the proletariat. Working class autonomy is manifested in the self-activity of the working class independent of formal organizations and representations, the multiplicity of forms that struggles take, and the role of class composition in shaping the overall balance of power in capitalist societies, not least in the relationship of class struggles to the character of capitalist crises. Class composition analysis is applied here to narrate the recent history of capitalism leading up to the current crisis, giving particular attention to China and the United States. A global wave of struggles in the mid-2000s was constituitive of the kinds of working class responses to the crisis that unfolded in 2008-10. The circulation of those struggles and resultant trends of recomposition and/or decomposition are argued to be important factors in the balance of political forces across the varied geography of the present crisis. The whirlwind of crises and the autonomist perspective The whirlwind of crises (Marks, 2010) that swept the world in 2008, financial panic upon food crisis upon energy shock upon inflationary spiral, receded temporarily only to surge forward again, leaving us in a turbulent world, full of possibility and peril. Is this the end of Neoliberalism or its retrenchment? A new 1 Published under the Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis 468 New Deal or a new Great Depression? The end of American hegemony or the rise of an “imperialism with Chinese characteristics?” Or all of those at once? This paper brings the political tendency known as autonomist Marxism (H. -

Exploring Underwater Heritage in Croatia a Handbook Exploring Underwater Heritage in Croatia a Handbook

exploring underwater heritage in croatia a handbook exploring underwater heritage in croatia a handbook Zadar, 2009. AN ROMAN PERIOD SHIPWRECK WITH A CARGO OF AMPHORAE ROMaN PeRIOD ShIPWRecK IN The ČaVLIN ShaLLOWS There are several hundred Roman pe- riod shipwrecks in the Croatian part of the Adriatic Sea, the majority of which are devastated, but about a dozen of which have survived the ravages of time and unethical looters. They have been preserved intact, or with only minor damage, which offers underwater archaeologists an oppor- tunity for complete research. The very large number of Roman ship- wrecks is not unexpected, but speaks rather of the intensity of trade and importance of navigation on the eastern side of the Adriatic Sea, and of the dangers our sea hides. Roman period shipwrecks can be dated either by the type of cargo they carried or by some further analysis (the age of the wood, for example), and the datings range from the 4th century BC to the 6th century. The cargos of these ships were varied: from fine pot- tery, vessels and plates, stone construction elements and brick to the most frequent cargo – amphorae. The amphora was used as packag- ing from the period of the Greece colonisation to the late Roman and the Byzantine supremacy. There are remains of shipwrecks with cargos of amphorae that can be researched on the seabed, covered by Archaeological underwater excavation with the aid of a water dredge protective iron cages, and there are those that, as per documentation, need to be raised to the surface and presented on land. -

Displacement and Exile in Evelyn Waugh's Post-War Fiction

Brno Studies in English Volume 42, No. 2, 2016 ISSN 0524-6881 DOI: 10.5817/BSE2016-2-6 Carlos Villar Flor Displacement and Exile in Evelyn Waugh’s Post-War Fiction Abstract Evelyn Waugh’s later fiction, especially his acclaimed trilogy known as Sword of Honour, is an indispensable source for a first-hand depiction of Britain’s in- volvement in the Second World War. Waugh’s millitary service in Croatia from 1944 to 1945 strengthened his concern for the predicament of the displaced per- sons and exiles he met there. Perhaps the clearest evidence of this new aware- ness is the privileged space that such characters find in these stories and the degree to which their suffering permeates the narratives they inhabit. My paper discuses Waugh’s treatment of displacement and exile in the final stages of the war trilogy and provides a historical background to his presentation of displaced persons, using Papastergiadis’s concept of deterritorialization as analytical tool. Keywords Evelyn Waugh; Sword of Honour; Scott-King’s Modern Europe; displacement; war refugees; World War II in literature For a first-hand depiction of Britain’s involvement in the Second World War, Evelyn Waugh’s later fiction is an indispensable source, especially his war trilogy known as Sword of Honour, which has received considerable critical acclaim.1 Very little, however, has been said about Waugh’s treatment of displacement and exile, even though these issues play a vital role in the final stages of the war tril- ogy. My paper sets out to fill this critical gap by providing a historical background to Waugh’s presentation of displaced persons, individuals removed from their na- tive country as refugees or prisoners who have managed to survive the slaughter but at the cost of becoming homeless, dispossessed and materially or spiritually humiliated. -

Hrvatski Jadranski Otoci, Otočići I Hridi

Hrvatski jadranski otoci, otočići i hridi Sika od Mondefusta, Palagruţa Mjerenja obale istoĉnog Jadrana imaju povijest; svi autori navode prvi cjelovitiji popis otoka kontraadmirala austougarske mornarice Sobieczkog (Pula, 1911.). Glavni suvremeni izvor dugo je bio odliĉni i dosad još uvijek najsustavniji pregled za cijelu jugoslavensku obalu iz godine 1955. [1955].1 Na osnovi istraţivanja skupine autora, koji su ponovo izmjerili opsege i površine hrvatskih otoka i otoĉića većih od 0,01 km2 [2004],2 u Ministarstvu mora, prometa i infrastrukture je zatim 2007. godine objavljena opseţna nova graĊa, koju sad moramo smatrati referentnom [2007].3 No, i taj pregled je manjkav, ponajprije stoga jer je namijenjen specifiĉnom administrativnom korištenju, a ne »statistici«. Drugi problem svih novijih popisa, barem onih objavljenih, jest taj da ne navode sve najmanje otoĉiće i hridi, iako ulaze u konaĉne brojke.4 Brojka 1244, koja je sada najĉešće u optjecaju, uopće nije dokumentirana.5 Osnovni izvor za naš popis je, dakle, [2007], i u graniĉnim primjerima [2004]. U napomenama ispod tablica navedena su odstupanja od tog izvora. U sljedećem koraku pregled je dopunjen podacima iz [1955], opet s obrazloţenjima ispod crte. U trećem koraku ukljuĉeno je još nekoliko dodatnih podataka s obrazloţenjem.6 1 Ante Irić, Razvedenost obale i otoka Jugoslavije. Hidrografski institut JRM, Split, 1955. 2 T. Duplanĉić Leder, T. Ujević, M. Ĉala, Coastline lengths and areas of islands in the Croatian part of the Adriatic sea determined from the topographic maps at the scale of 1:25.000. Geoadria, 9/1, Zadar, 2004. 3 Republika Hrvatska, Ministarstvo mora, prometa i infrastrukture, Drţavni program zaštite i korištenja malih, povremeno nastanjenih i nenastanjenih otoka i okolnog mora (nacrt prijedloga), Zagreb, 30.8.2007.; objavljeno na internetskoj stranici Ministarstva. -

Cape Mimoza Tourist Complex About Atlas Group

Cape Mimoza Tourist complex About Atlas Group Atlas Group has over 30 members operating in the area of banking, financial services, insurance, real estate, production, tourism, media, education, culture and sport. Our companies have offices in Montenegro, Serbia, Cyprus and Russia Atlas Group is organised as a modern management unit with a main objective to increase the value of all member companies by improving performance, investing in new projects and creating of synergy between the member companies. Atlas Group operates in line with global trends promoting sustainable development and utilization of renewable energy sources. Philanthropic activities conducted through the Atlas Group Foundation, which is a member of the Clinton Global Initiative. Atlas Bank was awarded the status of the best Bank in Montenegro, and Atlas Group as best financial group for 2009. by world economy magazine "World finance’’. In order to promote its mission Atlas Group has hosted many famous personalities from the spheres of politics, business, show business and arts. About Montenegro Located in Southeast Europe in the heart of Mediterranean. Extreme natural beauty and cultural – historical heritage (4 national parks, Old town Kotor under UNESCO protection). Area: 13.812 km2; population: 620.000; climate: continental, mediterranean and mountain; Capital city Podgorica with around 200.000 inhabitants. Borders with Croatia, BIH, Serbia, Albania and South part faces Adriatic Sea. Traffic connection: airports Podgorica, Tivat in Montenegro and airport in Dubrovnik, Croatia, port of Bar and Porto Montenegro, good connection of roads with international traffic. Currency: EUR Achieved political and economic stability – in the process of joining: EU, WTO and NATO Economy is largely oriented towards real estate and tourism development– stimulative investment climate (income tax 9%, VAT 17%, customs rate 6,6%, tax on real estate transaction 3%). -

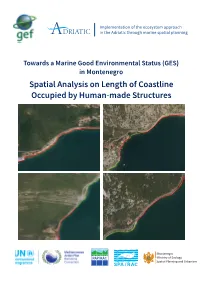

Spatial Analysis on Length of Coastline Occupied by Human-Made Structures

Towards a Marine Good Environmental Status (GES) in Montenegro Spatial Analysis on Length of Coastline Occupied by Human-made Structures Logos en anglais, avec versions courtes des logos ONU Environnem ent et PAM La version longue des logos ONU Environnem ent et PAM doit être utilisée dans les docum ents ou juridique Ls.a v ersio ncour te des logos est destin e tous les produit sde com m unicati otonurn s vers le public. Author: Željka Čurović, architect and landscape planner, Montenegro Graphic design: Old School S.P. Cover image: Examples of defining the type of coastline along the main road in the Bay of Kotor The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This study was prepared by PAP/RAC, SPA/RAC, UNEP/MAP, and the Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro within the GEF Adriatic Project and supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Spatial Analysis on Length of Coastline Occupied by Human-made Structures Table of contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Previous analyses ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

News-Agencies

Case Study Authors Laura Juntunen Hannu Nieminen THE FUTURE OF NATIONAL NEWS AGENCIES IN EUROPE Case study 3 2019 Supported by the LSE Knowledge Exchange and Impact Fund 2 The changing relation between news agencies and the state Abstract This case study analyses the relationship between European news agencies and the state. On the basis of interviews, official documents and secondary sources, we examine recent developments in the relationship with the state in a sample of four countries – Finland, France, Poland and Spain – representing different kinds of media systems. While the evolution of this relationship has been different and unique in each country, they are all bound by the competition rules of the European Union, and the challenges that the agencies face are similar. In general, European news agencies are struggling to keep their basic news services profitable. We argue that in the age of fake news and disinformation the social and democratic value of these news services is much greater than their economic value to their owners. From the democracy perspective, these services can be understood as a public good, and therefore the subsidising of content with a high information value can be in the public interest if certain preconditions are met. At the same time, safeguarding the editorial, and in particular the structural, independence of the agencies from political control is essential. Funding The Future of National News Agencies in Europe received funding from a number of sources: Media Research Foundation of Finland (67 285 euros); Jyllands-Posten Foundation, Denmark (15 000 euros); LSE Knowledge Exchange and Impact (KEI) Fund, UK (83 799 pounds) (only for impact, not for research); University of Helsinki, Finland (9 650 euros); and LSE Department of Media and Communications, UK (4 752 pounds). -

The Croatian Ustasha Regime and Its Policies Towards

THE IDEOLOGY OF NATION AND RACE: THE CROATIAN USTASHA REGIME AND ITS POLICIES TOWARD MINORITIES IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA, 1941-1945. NEVENKO BARTULIN A thesis submitted in fulfilment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales November 2006 1 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Nicholas Doumanis, lecturer in the School of History at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia, for the valuable guidance, advice and suggestions that he has provided me in the course of the writing of this thesis. Thanks also go to his colleague, and my co-supervisor, Günther Minnerup, as well as to Dr. Milan Vojkovi, who also read this thesis. I further owe a great deal of gratitude to the rest of the academic and administrative staff of the School of History at UNSW, and especially to my fellow research students, in particular, Matthew Fitzpatrick, Susie Protschky and Sally Cove, for all their help, support and companionship. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Department of History at the University of Zagreb (Sveuilište u Zagrebu), particularly prof. dr. sc. Ivo Goldstein, and to the staff of the Croatian State Archive (Hrvatski državni arhiv) and the National and University Library (Nacionalna i sveuilišna knjižnica) in Zagreb, for the assistance they provided me during my research trip to Croatia in 2004. I must also thank the University of Zagreb’s Office for International Relations (Ured za meunarodnu suradnju) for the accommodation made available to me during my research trip. -

The Centennial of the Conflagration at the Slovenian Cultural Centre in Trieste

Fire in the Roof, Truth in the Air: The Centennial of the Conflagration at the Slovenian Cultural Centre in Trieste 22. 3. 2021 Številka: 15/2021 Avtor: Ivan Smiljanić Drawing: Zoran Smiljanić July 2020 marked the hundredth anniversary of the fire at the Slovenian Cultural Centre in Trieste also known as the National Hall (Narodni dom). The event, because of its dramatic quality and consequences, is well-known in Slovenia, and has (once again) become the subject of heated debate. In the month of July, it was possible to read many things about the Trieste National Hall in the Slovenian media, and the writers all agreed about the most important elements of the incident including its cause and the order in which events unfolded on July 13, 1920. The problem is that we read very many different interpretations of the same incident in accounts from beyond our western border. The actual fire begins to be lost between new (and newer) interpretations and reinterpretations, and the abundance of contradictory information. Not only the event itself, but also its meaning in the wider historical context, becomes indistinct. This is counterproductive. Of course, it is good to have many sources available when considering the fire, sources from which we can compose a complete picture. But when these sources arise from specific (and differing) motives, they are useful for the analysis of discourses but considerably less so in the search for historical truth. But let's take a step back. It has become questionable whether the concept of historical truth really exists. Historians in the nineteenth century idealistically believed that it was possible to extract a refined truth from the careful study of historical sources. -

Comparative European Journalism: the State of Current Research Dr Henrik Örnebring Axess Research Fellow in Comparative European Journalism

WORKING PAPER Comparative European Journalism: e State of Current Research Dr Henrik Örnebring January 2009 Funded by: Ax:son Johnson Foundation Comparative European journalism: the state of current research Dr Henrik Örnebring Axess Research Fellow in Comparative European Journalism Introduction Research on different aspects of European journalism is a growth area. The study of media and journalism from a particular ‘European’ angle (e.g. studying EU reporting and news flows across Europe; comparing European media policies; examining the nature and character of a ‘European public sphere’) began to coalesce as a field in the 1990s (e.g. Machill, 1998; Morgan, 1995; Ostergaard, 1993; Schlesinger, 1999; Venturelli, 1993) – particularly the study of media policy across Europe (e.g. Collins, 1994; Dyson and Humphreys, 1990; Humphreys, 1996). Earlier studies of Europe and the media exist (e.g. Blumler and Fox, 1983; Kuhn, 1985; McQuail and Siune, 1986), but in general academic interest seems to have begun in earnest in the 1990s and exploded in the 2000s (e.g. Baisnée, 2002, 2007; Chalaby, 2002, 2005; Downey and Koenig, 2006; Gleissner and de Vreese, 2005; Groothues, 2004; Hagen, 2004; Koopmans and Pfetsch, 2004; Machill et al., 2006; Russ‐Mohl, 2003; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000; Trenz, 2004). The 2000s has seen a particular surge of academic interest in European journalism, reporting on Europe and the EU, the possible emergence of a ‘European’ public sphere and the role of news and journalism in that emergence. This surge has been influenced both by a parallel increase in interest in comparative studies of journalism in general (Deuze, 2002; Hanitzsch, 2007, 2008; Weaver and Löffelholz, 2008) as well as increased interest from the EU institutions themselves (the European Commission in particular) in the role of mediated communication – an interest made manifest in the 2006 White Paper on a European Communications Policy and related publications (European Commission, 2006, 2007). -

Bernarr Macfadden, Benito Mussolini and American Fascism in the 1930S

Sport in Society Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcss20 Building American Supermen? Bernarr MacFadden, Benito Mussolini and American fascism in the 1930s Ryan Murtha , Conor Heffernan & Thomas Hunt To cite this article: Ryan Murtha , Conor Heffernan & Thomas Hunt (2020): Building American Supermen? Bernarr MacFadden, Benito Mussolini and American fascism in the 1930s, Sport in Society, DOI: 10.1080/17430437.2020.1865313 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1865313 Published online: 31 Dec 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 65 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fcss20 SPORT IN SOCIETY https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1865313 Building American Supermen? Bernarr MacFadden, Benito Mussolini and American fascism in the 1930s Ryan Murtha, Conor Heffernan and Thomas Hunt Kinesiology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In 1931, Bernarr MacFadden, America’s self-proclaimed prophet of phys- Physical culture; ical culture joined forces with Italian dictator Bennito Mussolini in an nationalism; fascism; attempt to train a new generation of Italian soldiers. Done as part of masculinity; Second World MacFadden’s own attempts to secure a position within President’s War Roosevelt’s cabinet, MacFadden’s trip has typically been depicted as an odd quirk of Italian-American relations during this period. Italian histo- rians have viewed the collaboration as an indication of Mussolini’s com- mitment to strength and gymnastics for nationalist ends.