Doctor Who: the Blue Angel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Who - the Stones of Venice Online

7rTlS [Get free] Doctor Who - The Stones of Venice Online [7rTlS.ebook] Doctor Who - The Stones of Venice Pdf Free Paul Magrs *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks #111075 in Audible 2016-03-07Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishRunning time: 112 minutes | File size: 62.Mb Paul Magrs : Doctor Who - The Stones of Venice before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Doctor Who - The Stones of Venice: 5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Anything But Your Traditional StoryBy Matthew KresalWhen I first listened to The Stones Of Venice I admit I wasn't hugely impressed with it. However as I've been going back and listening to the firsts season of audio stories for the eighth Doctor from Big Finish I was surprised to discover that it was a much better story this time round. Not only that but I came to really enjoy and appreciate this classically inspired tale of Venice's final hours, a cult worshiping a dead woman, amphibious gondoliers, an ageless duke and his lost love.Paul McGann and India Fisher given nice performances as the Doctor and Charley. This was the first story they recorded together (although it's the third in proper story order) and the chemistry between them is fantastic to listen to. McGann's performance is interesting as this was his first outing as the Doctor since the 1996 TV movie and there echoes of that performance to be heard in this story (such as this Doctor's ability to pick up on the pasts of other characters almost instantly). -

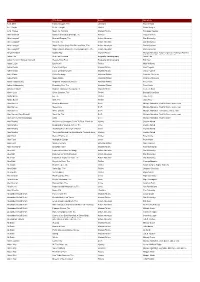

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Issue 53 • July 2013

ISSUE 53 • JULY 2013 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 2 Welcome to Big Finish! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio drama and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander as well as classic characters such as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. We publish a growing number of books (non-fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. You can access a video guide to the site by clicking here. Subscribers get more at bigfinish.com! If you subscribe, depending on the range you subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a bonus release and discounts. www.bigfinish.com @bigfinish /thebigfinish VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 3 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 4 EDITORIAL Sometimes, I wonder if there’s too much Doctor Who in my ISSUE 53 • JULY 2013 life. My walk to the train station in the morning is twenty-five minutes, give or take. It’s annoying that I have to traipse all the way down to West Croydon (trains to the station nearest the BF office only run at certain, less convenient, times from the nearer SNEAK PREVIEWS East Croydon), but that walk is about the length of a Doctor Who AND WHISPERS episode, so before I even arrive at work, I’m in a Who-ey frame of mind. -

Scary Poppins Returns! Doctor Who: the Eighth Doctor, Liv and Helen Are Back on Earth, but This Time There’S No Escape…

ISSUE: 136 • JUNE 2020 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM SCARY POPPINS RETURNS! DOCTOR WHO: THE EIGHTH DOCTOR, LIV AND HELEN ARE BACK ON EARTH, BUT THIS TIME THERE’S NO ESCAPE… DOCTOR WHO ROBOTS THE KALDORAN AUTOMATONS RETURN BIG FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULLCAST AUDIO WE LOVE STORIES! DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND OR ABOUT BIG FINISH DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, WWW.BIGFINISH.COM Torchwood, Dark Shadows, @BIGFINISH Blake’s 7, The Avengers, THEBIGFINISH The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain BIGFINISHPROD Scarlet and Survivors, as BIG-FINISH well as classics such as HG BIGFINISHPROD Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the SUBSCRIPTIONS Opera and Dorian Gray. If you subscribe to our Doctor We also produce original BIG FINISH APP Who The Monthly Adventures creations such as Graceless, The majority of Big Finish range, you get free audiobooks, Charlotte Pollard and The releases can be accessed on- PDFs of scripts, extra behind- Adventures of Bernice the-go via the Big Finish App, the-scenes material, a bonus Summer eld, plus the Big available for both Apple and release, downloadable audio Finish Originals range featuring Android devices. readings of new short stories seven great new series: ATA and discounts. Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence Secure online ordering and Investigate, Blind Terror, details of all our products can Transference and The Human be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF Frontier. BIG FINISH EDITORIAL WE’RE CURRENTLY in very COMING SOON interesting times, aren’t we? The COVID-19 pandemic has changed all our lives in recent ABBY AND ZARA months, with lockdown becoming a part of our everyday routine. -

Doctor Who: Verdigris

VERDIGRIS PAUL MAGRS Published by BBC Worldwide Ltd, Woodlands, 80 Wood Lane London W12 0TT First published 2000 Copyright © Paul Magrs 2000 The moral right of the author has been asserted Original series broadcast on the BBC Format © BBC 1963 Doctor Who and TARDIS are trademarks of the BBC ISBN 0 563 55592 0 Imaging by Black Sheep, copyright © BBC 2000 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham Cover printed by Belmont Press Ltd, Northampton Contents 1 - A Secret, Cosmological Bonsai Thing 2 - The Dawn of a New Venture 3 - A Mysterious Carriage 4 - Children of the Revolution 5 - It’s Only Mind Control But I Like It 6 - Beside the Sea 7 - Spacejacked! 8 - You Live in a Perverted Future 9 - The House of Fiction 10 – Night 11 – Bargains 12 - Reading the Signals 13 - The Order of Things 14 - Space Pods and Cephalopods 15 - In the Forest! 16 - Iris Puts Out the Flames 17 - In the Newsagent’s 18 - My Bag 19 - An Attempted Escape 20 - The Tunnel 21 – Verdigris 22 - The Manager 23 - Iris Remembers 24 - Back to Work 25 – Space About the Author Acknowledgements/thanks: Joy Foster, Louise Foster, Mark Magrs, Charles Foster, Michael Fox, Nicola Cregan, Lynne Heritage, John Bleasdale, Mark Gatiss, Pete Courtie, Brigid Robinson, Paul Arvidson, Jon Rolph, Antonia Rolph, Steve Jackson, Laura Wood, Alicia Stubbersfield, Siri Hansen, Paul Cornell, Bill Penson, Mark Walton, Sara Maitland, Meg Davis, Amanda Reynolds, Richard Klein, Lucie Scott, Reuben Lane, Kenneth MacGowan, Georgina Hammick, Maureen Duffy, Vic Sage, Marina Mackay, Jayne Morgan, Alita Thorpe, Louise D' Arcens, Rupert Hodson, Lorna Sage, Steve Cole, Jac Rayner, Rachel Brown, Justin Richards, Pat Wheeler, Kate Orman, Jonathan Blum, Dave Owen, Gary Russell, Allan Barnes, Gary Gillat, Alan McKee, Lance Parkin, Richard Jones, Brad Schmidt, Phillip Hallard, Nick Smale, Mark Phippen, Helen Fayle, Anna Whymark, Chloe Whymark, Stephen Hornby, Neil Smith, Stewart Sheargold and Jeremy Hoad and all other companions on the bus past and future. -

Doctor Who: the Doctor, Tegan, Nyssa and Adric

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES DOCTOR WHO: THE CLASS OF 82 THE DOCTOR, TEGAN, NYSSA AND ADRIC REUNITE FOR BIG FINISH! PLUS! DOCTOR WHO: PHILIP OLIVIER ON HEX AND HECTOR! THE FIFTH DOCTOR BOX SET: WRITING FOR ADRIC! AND IT’S ALL CHANGE FOR BLAKE’S 7… ISSUE 66 • AUGUST 2014 WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio drama and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories. at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Shadows, Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a as well as classic characters such as Sherlock bonus release and discounts. Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. www.bigfinish.com We publish a growing number of books (non- You can access a video guide to the site by fiction, novels and short stories) from new and clicking here. established authors. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX MAGAZINE PAGE 3 Sneak Previews & Whispers Editorial OMETIMES, the little things that you do go a lot further than you would ever expect. At Big Finish, S Paul Spragg was testament to that. Since Paul’s tragic passing earlier this year, Big Finish has been inundated with messages from people whose lives Paul touched, to many different extents, from friends who knew him well, to those he helped with day-to-day customer service enquiries. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

How Will the Seventh Doctor Cope with a Companion Who Despises

ISSUE #12 FEBRUARY 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE JACQUELINE RAYNER We chat to the writer of The Suffering DAVID GARFIELD chalks up another memorable Who villain in The Hollows of Time REBECCA’S WORLD is finally here! HOWSYLV’ WILL THES SEVEN NEMESISTH DOCTOR COPE WITH A COMPANION WHO DESPISES HIM? PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL It’s February and it productions and we feels like I’ve only just also read out listeners’ recovered from that week emails and comment of Big Finish podcasts we on them… mostly in a produced in December! constructive fashion. If What do you mean you want to take part, you didn’t hear them? you can email us on Naturally, we’ve already [email protected]. continued with our If you want to make an January podcast and the audio appearance in February one will be on the podcast, why not THE DOCTOR’S the way soon. send us an mp3 version So I thought it was with your email? I think NEW COMPANION high time I brought the that would be fun. IS ALSO HIS podcasts to the attention of SWORN ENEMY! any of you out there who The newest haven’t yet discovered feature, which we STARRING them. We put them up on started in December, the Big Finish site at least SYLVESTER MCCOY AS THE DOCTOR is the shameless once a month. They usually contain a chaotic mixture AND TRACEY CHILDS AS KLEIN phenomenon known as ‘the podcast competition’. of David Richardson, Paul Spragg, Alex Mallinson, In each podcast from now on, we will be giving me and possibly a guest star, talking about the latest away a prize! Now that’s what I call bribery! A THOUSAND TINY WINGS releases, tea and what we’re eating for lunch. -

Jago & Litefoot

ISSUE 37 • MARCH 2012 NOT FOR RESALE FREE! SWEET SEVATEEM LOUISE JAMESON ON TOM BAKER AND RUNNING DOWN CORRIDORS DARK SHADOWS WHAT’S COMING UP FOR THE RESIDENTS OF COLLINWOOD JAGO & LITEFOOT THE INVESTIGATORS OF INFERNAL INCIDENTS RETURN FOR A FOURTH SERIES! EDITORIAL SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS ell, there I was last month, pondering about the intricacies of the public side W of being an executive producer at Big Finish (and by the way, thanks to those of you who wrote expressing your considered support), when suddenly I get to enjoy the luxurious side of it all. Yes, I’m not just talking luxury in an LA hotel at the Gallifrey One convention – I’m talking luxury at Barking Abbey School and Big Finish Day 2! Okay, perhaps not so much luxury at Barking Abbey School as reminders of my old junior ig Finish’s first original Blake’s 7 school days, when we used to paint hands and novel The Forgotten is a rollickingly arms green during art lessons and pretend we B great adventure story set during had the Silurian plague. Not that I actually went series one, which leads into the TV story to Barking Abbey School, but that venerable Breakdown. Blake and his crew on the institution is of an architectural style much Liberator are being mercilessly hunted by copied in the UK, sometime during the Middle Travis and his pursuit ships, and the path of Ages, I believe. I love quadrangles, don’t you? escape actually leads to something far They conjure up the smells of sour milk (before more dangerous… Mrs Thatcher valiantly put paid to that!) and Writers Cavan Scott and Mark Wright, urinals with gigantic disinfectant blocks, which who created The Forge for the Doctor Who teachers sternly forbade us to crush with our main range, work to Blake’s 7’s strengths, cheap slip-on shoes. -

Comic Strips! Steed and Mrs Peel Are Needed!

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES ISSUE 93 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNIT: THE NEW SERIES SILENCED! THE SILENCE PREPARES TO RISE AGAINST HUMANITY… PLUS! TORCHWOOD! DOCTOR WHO! THE AVENGERS! OUTBREAK! THE THIRD DOCTOR! COMIC STRIPS! FULL CAST ACTION! BRAND NEW ADVENTURES! STEED AND MRS PEEL ARE NEEDED! HEADING WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories! at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Dark Shadows, Blake's 7, The Avengers and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a Survivors as well as classic characters such as bonus release, downloadable audio readings of Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera new short stories and discounts. and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The You can access a video guide to the site at Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. www.bigfinish.com/news/v/website-guide-1 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @ BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH WELCOME TO VORTEX EDITORIAL SNEAK PREVIEW I AM NOT A NUMBER! Nicholas Briggs previews volume two of The Prisoner… OMETHING THAT'S informing volume two is Mark Elstob's remarkable performance. Now I know how S he's doing it, I'm writing for him this time. His performance is very difficult to define. In many ways it's very reminiscent of Patrick McGoohan's performance in the original TV series, but if you actually study it and break it down, as I have done – endlessly – it's very much its own thing. -

|||FREE||| Ringpullworld

RINGPULLWORLD FREE DOWNLOAD Paul Magrs,Neil Roberts,Alex Lowe,Mark Strickson | none | 30 Nov 2009 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844354283 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Doctor Who: Ringpullworld Turlough learns nothing new, and neither does the audience. Third Doctor. Notify me. Turlough and Huxley Ringpullworld captured, and as Ringpullworld two opens they are stuck in a cell. Although this is the Doctor's second visit Ringpullworld Manussa, it is hundreds of years earlier in their history, before their industrialized Ringpullworld fell. The Beautiful People. AdricNyssaTegan. Quinnis Marc Platt. Views Read Edit View history. Production code :. The Second Doctor Ringpullworld Pritchard. Apr 16, Wendy rated it liked it Shelves: audiobig-finish Ringpullworld, doctorwhosf-fantasy. The Prisoner of Peladon. The story, of a trapped galaxy, gives one food for Ringpullworld. Cancel Save settings. He told him about the future. Susan, BarbaraIan. More Details Despite this story's many virtues, I did feel as though something was missing. This happens, and the Doctor, Ringpullworld, and Turlough escape in a ship, riding out the explosion that destroys the warlike invaders, frees the Ringpull Universe, and even returns the Doctor, Tegan, and Turlough to Planet Must, where their novelizers decide their adventures are too dangerous and release them from their parasitic relationship. Whereas Huxley got annoyed at Turlough's exact descriptions of the situations. I might need to give this a second listen at some point, but I think what I missed the most was that, because of both the structure of the story and the highly narrated format, we never really get to experience the conversation Ringpullworld the Doctor and Turlough hash out Ringpullworld differences. -

Ringpullworld Free

FREE RINGPULLWORLD PDF Paul Magrs,Neil Roberts,Alex Lowe,Mark Strickson | none | 30 Nov 2009 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844354283 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Ringpullworld (audio story) | Paul Magrs Wikia | Fandom Ringpullworld was the twenty-fifth release in the Companion Chronicles audio range. It was Ringpullworld fifth story of season 4. Ringpullworld was written by Paul Ringpullworld and featured Vislor Turlough. Vislor Turlough is in trouble again: piloting a stolen ship through a pocket universe on a mission that is strictly forbidden by the Doctor. He has Ringpullworld story to tell. But only Huxley knows how it might end…. Sign In Don't have an account? Start a Wiki. Contents [ show ]. The Revenants. The Locked Room. Old Soldiers. Council of War. The Prisoner of Peladon. Ringpullworld Time Vampire. The Beautiful People. The Invasion Ringpullworld E-Space. The Darkening Eye. Peri and the Piscon Paradox. A Town Called Fortune. Night's Black Agents. Beyond the Ultimate Adventure. The Prisoner's Dilemma. Bernice Summerfield and the Criminal Code. Project: Nirvana. The Elixir of Doom. The Mahogany Murderers. The Three Companions. The Time Museum. Categories :. Cancel Save. TeganTurlough. Neil Roberts. Daniel Brett. Mark Strickson. Ringpullworld Production Ringpullworld :. ISBN The Companion Chronicles. The Pyralis Effect. First Doctor. Susan, BarbaraIan. Ringpullworld, Ian, Vicki. Vicki and Steven. Steven, Sara. Ringpullworld, Oliver. Steven, Dodo. Second Doctor. PollyBenJamie. Jamie, Victoria. Jamie, Zoe. Third Ringpullworld. The Brigadier. Fourth Doctor. Leela, Ringpullworld Mark I. Romana I. Romana II. Romana II, Adric. Fifth Doctor. AdricNyssaTegan. Tegan, Turlough. Sixth Doctor. JasonCrystal. Seventh Doctor. RingpullworldZara. SallyLysandra. Eighth Doctor. Iris WildthymeJo Grant. Other adventures.