Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autologous Unilateral Breast Reconstruction with Venous Supercharged IMAP-Flaps: a Step by Step Guide of the Split Breast Technique

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Autologous Unilateral Breast Reconstruction with Venous Supercharged IMAP-Flaps: A Step by Step Guide of the Split Breast Technique , Kathrin Bachleitner * y, Laurenz Weitgasser y, Amro Amr and Thomas Schoeller Department of Hand, Breast, and Reconstructive Microsurgery, Marienhospital Stuttgart, 70199 Stuttgart, Germany; [email protected] (L.W.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (T.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-711-6489-7202 Both authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 13 August 2020; Accepted: 18 September 2020; Published: 20 September 2020 Abstract: Various techniques for breast reconstruction ranging from reconstruction with implants to free tissue transfer, with the disadvantage of either carrying a foreign body or dealing with donor site morbidity, have been described. In patients who had a unilateral mastectomy and offer a contralateral mamma hypertrophy a breast reconstruction can be performed with the excess tissue from the hypertrophic side using the split breast technique. Here a local internal mammary artery perforator (IMAP) flap of the hypertrophic breast can be used for reconstruction avoiding the downsides of implants or a microsurgical reconstruction and simultaneously reducing the enlarged donor breast in order to achieve symmetry. Methods: Between April 2010 and February 2019 the split breast technique was performed in five patients after mastectomy due to breast cancer. Operating time, length of stay, complications and the need for secondary operations were analyzed and the surgical technique including flap supercharging were described in detail. Results: All five IMAP-flaps survived and an aesthetically pleasant result could be achieved using the split breast technique. -

Model Keys Unit 1

Model Keys This section will supply you with the keys to several of the models found in the anatomy lab and the learning center. This does not include all the models. After the model keys in this section you will find keys to most of the Nystrom charts. In the anatomy lab there is a reference shelve that contains binders with the keys to most models, torsos and the Nystrom charts. Keys to some of the models are actually attached to the model. Chart keys can also be found either right on the chart or posted next to the chart. Unit 1 Numbered Skull (with colored numbers): g. internal occipital crest a. third molar (inside) b. incisive canal h. clivus (inside) c. infraorbital foramen i. foramen magnum d. infraorbital groove j. jugular foramen e. pterygopalatine fossa k. hypoglossal canal 6. Zygomatic bone l. cerebella fossa (inside) a. zygomaticofacial foramen m. vermain fossa (inside) 7. Sphenoid bone 4. Temporal bone a. medial pterygoid plate a. styloid process b. lateral pterygoid plate b. tympanic part c. lesser wing of sphenoid c. mastoid process (inside) d. mastoid notch d. greater wing of sphenoid 1. Frontal bone e. zygomatic process (inside) a. zygomatic process f. articular tubercle e. chiasmatic groove b. frontal crest (inside) g. stylomastoid foramen (inside) c. orbital part (inside) h. mastoid foramen f. anterior clinoid process d. supraorbital foramen i. external acoustic meatus (inside) e. anterior ethmoidal j. internal acoustic meatus g. posterior clinoid process foramen (inside) (inside) f. posterior ethmoidal k. carotid canal h. hypophyseal fossa foramen l. mandibular fossa (inside) g. -

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0 Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University SPLANCHNOLOGY, CARDIOVASCULAR AND IMMUNE SYSTEMS STUDY GUIDE Recommended by the Academic Council of Sumy State University Sumy Sumy State University 2016 1 УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 С72 Composite authors: V. I. Bumeister, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor; L. G. Sulim, Senior Lecturer; O. O. Prykhodko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant; O. S. Yarmolenko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant Reviewers: I. L. Kolisnyk – Associate Professor Ph. D., Kharkiv National Medical University; M. V. Pogorelov – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Sumy State University Recommended for publication by Academic Council of Sumy State University as а study guide (minutes № 5 of 10.11.2016) Splanchnology Cardiovascular and Immune Systems : study guide / С72 V. I. Bumeister, L. G. Sulim, O. O. Prykhodko, O. S. Yarmolenko. – Sumy : Sumy State University, 2016. – 253 p. This manual is intended for the students of medical higher educational institutions of IV accreditation level who study Human Anatomy in the English language. Посібник рекомендований для студентів вищих медичних навчальних закладів IV рівня акредитації, які вивчають анатомію людини англійською мовою. УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 © Bumeister V. I., Sulim L G., Prykhodko О. O., Yarmolenko O. S., 2016 © Sumy State University, 2016 2 Hippocratic Oath «Ὄμνυμι Ἀπόλλωνα ἰητρὸν, καὶ Ἀσκληπιὸν, καὶ Ὑγείαν, καὶ Πανάκειαν, καὶ θεοὺς πάντας τε καὶ πάσας, ἵστορας ποιεύμενος, ἐπιτελέα ποιήσειν κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμὴν ὅρκον τόνδε καὶ ξυγγραφὴν τήνδε. -

SŁOWNIK ANATOMICZNY (ANGIELSKO–Łacinsłownik Anatomiczny (Angielsko-Łacińsko-Polski)´ SKO–POLSKI)

ANATOMY WORDS (ENGLISH–LATIN–POLISH) SŁOWNIK ANATOMICZNY (ANGIELSKO–ŁACINSłownik anatomiczny (angielsko-łacińsko-polski)´ SKO–POLSKI) English – Je˛zyk angielski Latin – Łacina Polish – Je˛zyk polski Arteries – Te˛tnice accessory obturator artery arteria obturatoria accessoria tętnica zasłonowa dodatkowa acetabular branch ramus acetabularis gałąź panewkowa anterior basal segmental artery arteria segmentalis basalis anterior pulmonis tętnica segmentowa podstawna przednia (dextri et sinistri) płuca (prawego i lewego) anterior cecal artery arteria caecalis anterior tętnica kątnicza przednia anterior cerebral artery arteria cerebri anterior tętnica przednia mózgu anterior choroidal artery arteria choroidea anterior tętnica naczyniówkowa przednia anterior ciliary arteries arteriae ciliares anteriores tętnice rzęskowe przednie anterior circumflex humeral artery arteria circumflexa humeri anterior tętnica okalająca ramię przednia anterior communicating artery arteria communicans anterior tętnica łącząca przednia anterior conjunctival artery arteria conjunctivalis anterior tętnica spojówkowa przednia anterior ethmoidal artery arteria ethmoidalis anterior tętnica sitowa przednia anterior inferior cerebellar artery arteria anterior inferior cerebelli tętnica dolna przednia móżdżku anterior interosseous artery arteria interossea anterior tętnica międzykostna przednia anterior labial branches of deep external rami labiales anteriores arteriae pudendae gałęzie wargowe przednie tętnicy sromowej pudendal artery externae profundae zewnętrznej głębokiej -

Concerning Blood Supply of the Body Wall Cairns Base Hospital

Cairns Base Hospital Emergency Department Part 1 FACEM MCQs 1 Concerning blood supply of the body wall A Venous drainage follows the arteries B Anterior structures are supplied by the intercostal arteries C The thoracoepigastric vein joins the superior and inferior epigastric veins D the thoracoepigastric vein becomes prominent in inferior vena cava obstruction E The caput Medusae is commonly found in normal individuals 2 Concerning dermatomes of the body wall A The inguinal region is supplied by no B The nipple is supplied by T6 C The umbilicus is supplied by L1 D The infraclavicular region is supplied by C2 E The supraclavicular region is supplied by C1 3 Concerning joints of the thoracic wall A The manubriosternal joint is a secondary cartilaginous joint B All midline joints are of the primary cartilaginous type C The sternoclavicular joint is a typical synovial joint D All sternocostal joints are synovial joints st E The 1 sternocostal joint is a secondary cartilaginous joint 4 Concerning the intercostal space A The neurovascular bundle lies between the external and internal intercostals muscles B The intercostal vein is typically the most superior structure in the neurovascular bundle C All intercostals spaces are supplied by posterior intercostal arteries posteriorly st D The internal thoracic artery supplies the 1 4 intercostal spaces only E Intercostal nerves have no cutaneous supply 5 Concerning the diaphragm A The central tendon is at the level of L1 B The left dome rises to the ih intercostal space in full expiration C The -

The Surgical Anatomy of the Mammary Gland. Vascularisation, Innervation, Lymphatic Drainage, the Structure of the Axillary Fossa (Part 2.)

NOWOTWORY Journal of Oncology 2021, volume 71, number 1, 62–69 DOI: 10.5603/NJO.2021.0011 © Polskie Towarzystwo Onkologiczne ISSN 0029–540X Varia www.nowotwory.edu.pl The surgical anatomy of the mammary gland. Vascularisation, innervation, lymphatic drainage, the structure of the axillary fossa (part 2.) Sławomir Cieśla1, Mateusz Wichtowski1, 2, Róża Poźniak-Balicka3, 4, Dawid Murawa1, 2 1Department of General and Oncological Surgery, K. Marcinkowski University Hospital, Zielona Gora, Poland 2Department of Surgery and Oncology, Collegium Medicum, University of Zielona Gora, Poland 3Department of Radiotherapy, K. Marcinkowski University Hospital, Zielona Gora, Poland 4Department of Urology and Oncological Urology, Collegium Medicum, University of Zielona Gora, Poland Dynamically developing oncoplasty, i.e. the application of plastic surgery methods in oncological breast surgeries, requires excellent knowledge of mammary gland anatomy. This article presents the details of arterial blood supply and venous blood outflow as well as breast innervation with a special focus on the nipple-areolar complex, and the lymphatic system with lymphatic outflow routes. Additionally, it provides an extensive description of the axillary fossa anatomy. Key words: anatomy of the mammary gland The large-scale introduction of oncoplasty to everyday on- axillary artery subclavian artery cological surgery practice of partial mammary gland resec- internal thoracic artery thoracic-acromial artery tions, partial or total breast reconstructions with the use of branches to the mammary gland the patient’s own tissue as well as an artificial material such as implants has significantly changed the paradigm of surgi- cal procedures. A thorough knowledge of mammary gland lateral thoracic artery superficial anatomy has taken on a new meaning. -

Subject Index

Subject Index Achalasia Aspergillosis 190 -- tumorectomy 90, 91 - classification 391 Aspiration, pericardial 54 - cyst, preoperative localization 79 - dilatation 398 Atelectasis, postoperative 180 - diagnostic procedures, indications -- balloon systems with endoscopic Atkinson tube 287, 288 77 guidance 399, 400 Atrium, left, partial removal 180 - gynecomastia 87 -- balloon systems without endo Axillary approach 24 - inflammatory disease 86, 87 scopic guidance 400, 401 - mastectomy -- compared with esophagomyo Babcok vein stripper, in esopha -- extended radical (Urban's modi- tomy 391, 392 gectomy 328, 329 fication) 98, 99 -- Kaphingst dilator 399 Balloon catheter systems 270 -- modified radical 94-96 techniques 400, 401 Bilobectomy -- Patey's operation 96 -- Witzel dilator system 398, 399 lower 150, 151 -- radical (Rotter-Halsted modifica- - esophagomyotomy - upper 149 tion) 97, 98 -- lower sphincter Bochdalek hernia 217 -- skin incisions 94 --- dilatation compared with Bougienage -- subcutaneous 84, 85 391, 392 - blind dilatation 272 - periareolar incision 80, 81 --- indications 391 - Buess system 270, 271 - radiation ulcers 102 --- preoperative preparation 392 - guidewire systems -- latissimus dorsi flap 102 --- transabdominal approach -- balloon catheter systems 270 -- myocutaneous rectus flap 392-394 -- Celestin and Savary systems 103, 104 --- transthoracic approach 392, 269 -- omentoplasty 102, 103 394 -- Eder-Puestow system 266-269 -- thoracoepigastric flap 102 -- upper sphincter 388, 389 - Hendren and Hale electromagnetic - segmental -

Clinical Anatomy Flash Cards

! " #$$"" $ $%&'()'(*'+,)&*" front.card2.4.qxd 12/5/06 2:28 PM Page 1 Abdomen 2.4 Drainage of the Anterior Abdominal Wall 1 2 3 Transumbilical plane 4 5 6 Lymphatic Venous drainage drainage COA back.card2.4.qxd 12/4/06 3:16 PM Page 1 Drainage of the Anterior Abdominal Wall 1. axillary lymph nodes 2. axillary vein 3. thoracoepigastric vein 4. superficial inguinal lymph nodes 5. superficial epigastric vein 6. femoral vein Lymph superior to the transumbilical plane drains to the axil- lary lymph nodes, while lymph inferior to the plane drains to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. When flow in the supe- rior or inferior vena cava is blocked, anastomoses between their tributaries, that is, the thoracoepi- gastric vein, may pro- vide collateral circula- tion, allowing the ob- struction to be bypassed. Thoracoepigastric vein COA © 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins front.card2.36.qxd 12/5/06 1:20 PM Page 1 Abdomen 2.36 Portal System 1 3 4 2 6 5 7 Grant’s back.card2.36.qxd 12/4/06 3:28 PM Page 1 Portal System 1. inferior vena cava 2. hepatic portal vein 3. right gastric vein 4. splenic vein 5. superior mesenteric vein 6. inferior mesenteric vein 7. superior rectal veins Caput Medusae When scarring and fibrosis from cir- rhosis obstruct the portal vein, pres- sure in the portal vein rises and pro- duces portal hypertension. The blood then flows to into the systemic system at places of portal-systemic anastomo- sis, producing varicose veins. Caput medusae is caused by the veins of the anterior abdominal wall becoming dilated from portal hypertension. -

1 Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall 1

Chapter 1 Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall 1 Orhan E. Arslan 1.1 Introduction The abdominal wall encompasses an area of the body boundedsuperiorlybythexiphoidprocessandcostal arch, and inferiorly by the inguinal ligament, pubic bones and the iliac crest. Epigastrium Visualization, palpation, percussion, and ausculta- Right Left tion of the anterolateral abdominal wall may reveal ab- hypochondriac hypochondriac normalities associated with abdominal organs, such as Transpyloric T12 Plane the liver, spleen, stomach, abdominal aorta, pancreas L1 and appendix, as well as thoracic and pelvic organs. L2 Right L3 Left Visible or palpable deformities such as swelling and Subcostal Lumbar (Lateral) Lumbar (Lateral) scars, pain and tenderness may reflect disease process- Plane L4 L5 es in the abdominal cavity or elsewhere. Pleural irrita- Intertuber- Left tion as a result of pleurisy or dislocation of the ribs may cular Iliac (inguinal) Plane result in pain that radiates to the anterior abdomen. Hypogastrium Pain from a diseased abdominal organ may refer to the Right Umbilical Iliac (inguinal) Region anterolateral abdomen and other parts of the body, e.g., cholecystitis produces pain in the shoulder area as well as the right hypochondriac region. The abdominal wall Fig. 1.1. Various regions of the anterior abdominal wall should be suspected as the source of the pain in indi- viduals who exhibit chronic and unremitting pain with minimal or no relationship to gastrointestinal func- the lower border of the first lumbar vertebra. The sub- tion, but which shows variation with changes of pos- costal plane that passes across the costal margins and ture [1]. This is also true when the anterior abdominal the upper border of the third lumbar vertebra may be wall tenderness is unchanged or exacerbated upon con- used instead of the transpyloric plane. -

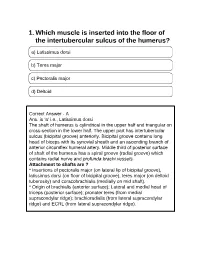

1. Which Muscle Is Inserted Into the Floor of the Intertubercular Sulcus of the Humerus?

1. Which muscle is inserted into the floor of the intertubercular sulcus of the humerus? a) Latissimus dorsi b) Teres major c) Pectoralis major d) Deltoid Correct Answer - A Ans. is 'a' i.e., Latissimus dorsi The shaft of humerus is cylindrical in the upper half and triangular on cross-section in the lower half. The upper part has intertubercular sulcus (bicipital groove) anteriorly. Bicipital groove contains long head of biceps with its synovial sheath and an ascending branch of anterior circumflex humeral artery. Middle third of posterior surface of shaft of the humerus has a spiral groove (radial groove) which contains radial nerve and profunda brachi vessels. Attachment to shafts are ? * Insertions of pectoralis major (on lateral lip of bicipital groove), latissimus dorsi (on floor of bicipital groove), teres major (on deltoid tuberosity) and coracobrachialis (medially on mid shaft). * Origin of brachialis (anterior surface); Lateral and medial head of triceps (posterior surface); pronater teres (from medial supracondylar ridge); brachioradialis (from lateral supracondylar ridge) and ECRL (from lateral supracondylar ridge). 2. At what level does the trachea bifurcates ? a) Upper border of T4 b) Lower border of T4 c) 27.5 cm from the incisors d) Lower border of T5 Correct Answer - B th Ans. is 'b' i.e., Lower border of T4 [Ref BDC S /e Volume 1 p. 267] Trachea bifurcates at carina, at the level of lower border of T, or T4 - T5 disc space. 3. Cricoid cartilage lies at which vertebral level ? a) C3 b) C6 c) T1 d) T4 Correct Answer - B Ans. is 'b' i.e., C6 [Ref BDC 5I'Ve Vol. -

A Clinical Study on Women Presening with Mastalgia to a Tertiary Referral Centre in Southindia”

A DISSERTATION ON “A CLINICAL STUDY ON WOMEN PRESENING WITH MASTALGIA TO A TERTIARY REFERRAL CENTRE IN SOUTHINDIA” Dissertation submitted to THE TAMIL NADU DR.M.G.R.MEDICAL UNIVERISTY CHENNAI With partial fulfillment of the regulations For the Award of the degree M.S. (GENERAL SURGERY) BRANCH – I MADRAS MEDICAL COLLEGE, CHENNAI APRIL-2016 1 BONAFIDE CERTIFICATE Certified that this dissertation is the bonafide work of Dr.V.C.KALYANASUNDARABHARATHI on “A CLINICAL STUDY ON WOMEN PRESENING WITH MASTALGIA TO A TERTIARY REFERRAL CENTRE IN SOUTHINDIA” during his M.S. (General Surgery) course from July 2015 to September 2015 at the Madras Medical College and Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai – 600003. Prof.Dr.P.RAGUMANI. M.S. Prof.Dr.K.RAMASUBRAMANIAN, M.S., Director, Professor of General Surgery, Institute of General Surgery, Institute of General Surgery, Madras Medical College & Rajiv Madras Medical College & Gandhi Government Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, General Hospital, Chennai – 600 003. Chennai – 600 003. Prof.Dr.R.VIMALA M.D, Dean, Madras Medical College & Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai – 600 003. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my deep sense of gratitude to the DEAN, Madras Medical College and Prof.Dr.P.RAGUMANI M.S, Director, Institute of General Surgery, MMC & RGGGH, for allowing me to undertake this study on “A CLINICAL STUDY ON WOMEN PRESENING WITH MASTALGIA TO A TERTIARY REFERRAL CENTRE IN SOUTHINDIA” I was able to carry out my study to my fullest satisfaction, thanks to guidance, encouragement, motivation and constant supervision extended to me, by my beloved Unit Chief Prof.Dr.K.RAMASUBRAMANIAN M.S. -

BHT-011 Basic Phlebotomy Assistance Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Health Sciences

BHT-011 Basic Phlebotomy Assistance Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Health Sciences Block 4 TECHNIQUE OF BLOOD COLLECTION UNIT 10 Patient Preparation for Venipuncture 5 UNIT 11 Site Selection and Venipuncture 19 UNIT 12 Techniques for Collection of Blood Specimens 31 UNIT 13 Blood Collection in Special Cases and Sites 41 Technique of Blood Collection CURRICULUM DESIGN COMMITTEE Dr. A. K. Mandal Prof. Kolte Sachin Prof. T. K. Jena HOD, Department of Department of Pathology SOHS, IGNOU, Pathology, Dr. Baba Saheb VMMC and Safdurjung Hospital Maidan Garhi, New Delhi Ambedkar Medical College New Delhi New Delhi Dr. Neerja Sood Dr. Reeta Devi Assistant Professor (Sr. Scale) Prof. Neelkamal Kapoor Assistant Professor (Sr. Scale) SOHS, IGNOU, Maidan Garhi HOD, Department of SOHS, IGNOU New Delhi Pathology, AIIMS, Bhopal Maidan Garhi, New Delhi Dr. Biplab Jamatia Dr. Archana Bajpai Ms Laxmi Assistant Professor (Sr. Scale) Associate Professor Assistant Professor (Sr. Scale) SOHS, IGNOU, Maidan Garhi Transfusion Medicine SOHS, IGNOU, Maidan Garhi New Delhi AIIMS, Jodhpur New Delhi BLOCK PREPARATION TEAM Writers Unit 10 & 13 Unit 11 & 12 Prof. Neelkamal Kapoor Dr. Sachin Kolte HOD, Department of Professor, Department of Pathology, AIIMS, Bhopal Pathology, VMMC & Safdarjung Medical College, New Delhi EDITORIALTEAM Dr. Biplab Jamatia Dr. A. K. Sood Dr Prasenjit Das Assistant Professor (Sr. Scale) Senior Consultant, Associate Professor, Dept of SOHS, IGNOU Skill Training Cell, Pathology, All India Institute of Maidan Garhi, New Delhi SOHS, IGNOU Medical Sciences, New Delhi Dr. D. C. Jain Senior Consultant, Skill Training Cell, SOHS, IGNOU, New Delhi CO-ORDINATION Course Coordinator Prof. T. K.