Telenovela Returns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silva Jlbl Me Assis Int.Pdf

JÉFFERSON LUIZ BALBINO LOURENÇO DA SILVA Representações e recepção da homossexualidade na teledramaturgia da TV Globo nas telenovelas América, Amor à Vida e Babilônia (2005-2015) ASSIS 2019 JÉFFERSON LUIZ BALBINO LOURENÇO DA SILVA Representações e recepção da homossexualidade na teledramaturgia da TV Globo nas telenovelas América, Amor à Vida e Babilônia (2005-2015) Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Assis, para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História (Área de Conhecimento: História e Sociedade) Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Zélia Lopes da Silva. Bolsista: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Código de Financiamento 001. ASSIS 2019 Silva, Jéfferson Luiz Balbino Lourenço da S586r Representações e Recepção da Homossexualidade na Teledramaturgia da TV Globo nas telenovelas América, Amor à Vida e Babilônia (2005-2015) / Jéfferson Luiz Balbino Lourenço da Silva. -- Assis, 2019 244 p. : il., tabs. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp), Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Assis Orientadora: Zélia Lopes da Silva 1. Telenovela. 2. Representações. 3. Homossexualidade. 4. Recepção. I. Título. Este trabalho é dedicado a todos que reconhecem a importância sociocultural da telenovela brasileira. Dedico, especialmente, ao meu pai, José Luiz, (in memorian), meu maior exemplo de coragem, à minha mãe, Elenice, meu maior exemplo de persistência, à minha avó materna, Maria Apparecida (in memorian), meu maior exemplo de amor. E, também, a Yasmin Lourenço, Vitor Silva e Samara Donizete que sempre estão comigo nos melhores e piores momentos de minha vida. AGRADECIMENTOS A gratidão é a memória do coração. Antístenes Escrever uma dissertação de mestrado não é uma tarefa fácil; ao contrário, é algo ardiloso, porém, muito recompensador. -

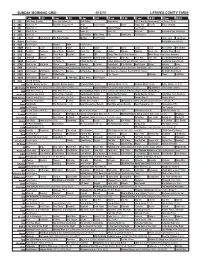

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

As Transformações Nos Contos De Fadas No Século Xx

DE REINOS MUITO, MUITO DISTANTES PARA AS TELAS DO CINEMA: AS TRANSFORMAÇÕES NOS CONTOS DE FADAS NO SÉCULO XX ● FROM A LAND FAR, FAR AWAY TO THE BIG SCREEN: THE CHANGES IN FAIRY TALES IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Paulo Ailton Ferreira da Rosa Junior Instituto Federal Sul-rio-grandense, Brasil RESUMO | INDEXAÇÃO | TEXTO | REFERÊNCIAS | CITAR ESTE ARTIGO | O AUTOR RECEBIDO EM 24/05/2016 ● APROVADO EM 28/09/2016 Abstract This work it is, fundamentally, a comparison between works of literature with their adaptations to Cinema. Besides this, it is a critical and analytical study of the changes in three literary fairy tales when translated to Walt Disney's films. The analysis corpus, therefore, consists of the recorded texts of Perrault, Grimm and Andersen in their bibliographies and animated films "Cinderella" (1950), "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" (1937) and "The little Mermaid "(1989) that they were respectively inspired. The purpose of this analysis is to identify what changes happened in these adapted stories from literature to film and discuss about them. Resumo Este trabalho trata-se, fundamentalmente, de uma comparação entre obras da Literatura com suas respectivas adaptações para o Cinema. Para além disto, é um estudo crítico e analítico das transformações em três contos de fadas literários quando transpostos para narrativas fílmicas de Walt Disney. O corpus de análise, para tanto, é composto pelos textos registrados de Perrault, Grimm e Andersen em suas respectivas bibliografias e os filmes de animação “Cinderella” (1950), “Branca de Neve e os Sete Anões” (1937) e “A Pequena Sereia” (1989) que eles respectivamente inspiraram. -

Universal Realty NBC 8 KGW News at Sunrise Today Gloria Estefan, Emilio Estefan, Bob Dotson Today Show II (N) Today Show III (N) Paid Million

Saturday, April 11, 2015 TV TIME MONDAY East Oregonian Page 7C Television > Today’s highlights Talk shows Gotham siders a life outside of White Pine 6:00 a.m. (42) KVEW Good Morning Gene Baur discuss pantry staples that Northwest will help you live a healthier life. (11) KFFX KPTV 8:00 p.m. Bay, Dylan (Max Thieriot) and WPIX Maury WPIX The Steve Wilkos Show A woman A cold case is re-opened as Gor- Emma (Olivia Cooke) help Nor- 6:30 a.m. (42) KVEW Good Morning has reason to believe that her husband don (Ben McKenzie) and Bullock man (Freddie Highmore) through Northwest is cheating and is trying to kill her. 7:00 a.m. (19) KEPR KOIN CBS This 1:00 p.m. KPTV The Wendy Williams (Donal Logue) investigate a serial a rough night. Also, Caleb (Kenny Morning Show killer known as Ogre in this new Johnson) faces a new threat. (25) KNDU KGW Today Show Gloria (19) KEPR KOIN The Talk (59) episode. At the same time, Fish and Emilo Estefan discuss, ‘On Your OPB Charlie Rose TURN: Washington’s Feet.’ WPIX The Steve Wilkos Show (Jada Pinkett Smith) plots her es- (42) KVEW KATU Good Morning 2:00 p.m. KOIN (42) KVEW The Doctors cape from The Dollmaker. Spies America KGW The Dr. Oz Show AMC 9:00 p.m. ESPN2 ESPN First Take KATU The Meredith Vieira Show (19) Hoarding: Buried Alive - Abe (Jamie Bell) is determined to WPIX Maury 3:00 p.m. KEPR KOIN Dr. Phil 8:00 a.m. -

Control Remoto

11111410 02/28/2008 09:39 p.m. Page 2 2B |EL SIGLO DE DURANGO | VIERNES 29 DE FEBRERO DE 2008 | TELEVISIÓN MELODRAMA | REBELDE LE CAMBIÓ LA VIDA Y AHORA CUMPLE SU SUEÑO Angelique Boyer cambió de look para Hoy en la TV su nuevo personaje. CANAL DE LAS ¿Alma de Hierro? ESTRELLAS 06:00 Primero Noticias 09:00 Hoy 12:00 Niña Amada Mía 13:00 Al Sabor del Chef 13:30 12 Corazones 14:30 Noticiero con Lolita Ayala 15:00 Xhdrbz ¡Para nada! 16:00 Al Diablo con Los Guapos Angelique Boyer chateó actuar? 17:00 La Rosa de Guadalupe ■ ¿Cuál es el personaje con el Hacer que no tengo frío cuan- 18:00 Palabra de Mujer con sus fans y respondió que más te has identificado? do estamos a menos dos 19:00 Tormenta en el Paraíso Ahorita ninguno quizá, Sandy es la grados, quitarme la bata 20:00 Las Tontas No Van Al todas y cada una de sus que quiere ser artista como yo lo y enseñar las pompas. Cielo quise ser. 21:00 Fuego en la Sangre preguntas ■ ¿Si no hubieras 22:00 Alma de Hierro ■ ¿Cómo ha cambiado la sido actriz, qué te 22:30 Noticiero con Joaquín AGENCIAS actuación tu vida? hubiera gustado López Dóriga Es difícil como me ha cambiado ser? 23:15 Televisa Deportes MÉXICO, DF.- La actriz An- la vida, todos mis momen- Bailarina de ballet o 23:30 El Notifiero con Brozo gelique Boyer, quien ENTÉRATE tos se han hecho de esto, de patinaje artístico. da vida al personaje ■ Angelique participa en la el elemento primordial de Sandy en la tele- nueva telenovela Alma de para el personaje es la ■ ¿Qué sentiste CANAL novela Alma de Hie- Hierro, de lunes a viernes, pasión que le pongo al cuando empezaste 5 rro, platicó con sus en punto de las 22:00 bailar y que es una la novela Alma fans en un chat orga- horas, por el Canal de chava sencilla. -

El Impacto De Las Series Españolas Televisivas En Las Redes Sociales Después De Su Difusión En Plataformas De Vídeo

MÁSTER EN MARKETING DIGITAL, COMUNICACIÓN Y REDES SOCIALES El impacto de las series españolas televisivas en las redes sociales después de su difusión en plataformas de vídeo Mayo 2019 1 MÁSTER EN MARKETING DIGITAL, COMUNICACIÓN Y REDES SOCIALES El impacto de las series españolas televisivas en las redes sociales después de su difusión en plataformas de vídeo Nombre del Alumno: Sonia Trujillo Vera Nombre del Tutor: Dr. Jorge Gallardo Camacho 2 Índice de contenidos 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ............................................................................................................. 10 2. MARCO TEÓRICO .......................................................................................................... 11 2.1 La llegada de Internet a la televisión tradicional ..................................................... 11 2.1.1 La televisión apuesta por integrarse en Internet .............................................. 12 2.1.2 Tipología de vídeo en Internet ........................................................................... 15 2.1.3 Perfil del consumidor de vídeo online y hábitos de consumo ......................... 19 2.2 Las redes sociales como las conocemos en la actualidad .................................... 20 2.2.1 Perfil de los usuarios y usos de las redes sociales.......................................... 23 2.2.2 Cómo influye la red social Twitter en la opinión pública .................................. 25 2.3 La audiencia social en TV frente a la audiencia tradicional ................................... 29 2.3.1 -

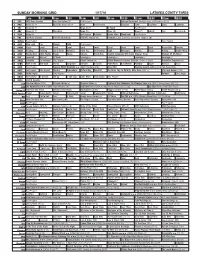

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

El Prejuicio Y La Palabra: Los Derechos a La Libre Expresión Y a La No Discriminación En Contraste

EL PREJUICIO YLA PALABRA: LOS DERECHOS ALA LIBRE EXPRESIÓN Y ALA NO DISCRIMINACIÓN EN CONTRASTE JESÚS RODRÍGUEZ ZEPEDA TERESA GONZÁLEZ LUNA CORVERA COORDINADORES SEGOB 1 Wl!!fi..~ CONSEJO NACIONAL PARA SECRETARIA DE GOBERNACIÓN J . , ,. PREVENIR LA DISCRIMINACIÓN ESTEREOTIPO RACISMO EXPRESION/ El prejuicio y la palabra: los derechos a la libre expresión y a la no discriminación en contraste Jesús Rodríguez Zepeda Teresa González Luna Corvera Coordinadores Jesús Rodríguez Zepeda · Gustavo Ariel Kaufman Article 19 · Juan Antonio Cruz Parcero Pedro Salazar Ugarte y Mayra Ortiz Ocaña José Woldenberg · Raúl Trejo Delarbre Marta Lamas · Amneris Chaparro Nicolás Alvarado · Luis González Placencia Darwin Franco Migues y Guillermo Orozco Gómez Carlos Pérez Vázquez Coordinadores: Jesús Rodríguez Zepeda y Teresa González Luna Corvera Coordinación editorial y diseño: Génesis Ruiz Cota Cuidado de la edición: Armando Rodríguez Briseño Primera edición: mayo de 2018 © 2018. Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación Dante 14, col. Anzures, del. Miguel Hidalgo, 11590, Ciudad de México www.conapred.org.mx isbn: 978-607-8418-37-4 Se permite la reproducción total o parcial del material incluido en esta obra, previa autorización por escrito de la institución. Ejemplar gratuito. Prohibida su venta. Impreso en México. Printed in Mexico Índice Introducción Jesús Rodríguez Zepeda y Teresa González Luna Corvera ..............7 El peso de las palabras: libre expresión, no discriminación y discursos de odio Jesús Rodríguez Zepeda .................................................................27 -

CABLEWORLD Guía De Programación De Televisión

Nº 312 • JUNIO 2021 • 4 € cableCABLEWORLD Nº 312 • JUNIO 2021 • 4 € JUNIO 2021 guia Guíade programación de programación de de tel televisiónevisión Especial: Amor de verano Brujas de Salem Miércoles 16 a las 15:00 h. Martes 8 y 15 , a las 22:00 h. NUEVOS CAPÍTULOS EN JUNIO DE LUNES A VIERNES A LAS 20:00H No faltes a clase con Sergio Fernández sumario junio 2021 CINE AMC ................................................................................ 8 Canal Hollywood ..................................................... 10 Sundance......................................................................12 AXN white ....................................................................15 TCM .................................................................................16 TNT ..................................................................................17 De Pelicula ................................................................. 28 ENTRETENIMIENTO AXN White ....................................................................15 Especial: Amor Cuando llega Crimen e Investigación ......................................... 21 de verano el amor 22 29 Fox Life ..........................................................................22 Llega el verano, suben las temperaturas, guar- Isabel Contreras es una joven privilegiada: es Fox .................................................................................23 damos la ropa de abrigo y surgen los amores hermosa y rica, sus padres la adoran y está com- de verano en los lugares más idílicos -

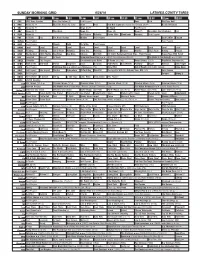

Sunday Morning Grid 6/26/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/26/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Red Bull Signature Series From Detroit. (N) Å Beach Volleyball 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Incredible Dog Challenge Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Earth 2050 FabLab 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Happy Yoga With Sarah 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. (PG-13) The World Is Not Enough ›› (1999) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Un recuerdo para Rubé Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE ARQUITETURA E URBANISMO O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Aline Stefânia Zim Brasília - DF 2018 1 ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora em Arquitetura. Área de Pesquisa: Teoria, História e Crítica da Arte Orientador: Prof. Dr. Flávio Rene Kothe Brasília – DF 2018 2 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO DA ARQUITETURA Tese aprovada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora pelo Programa de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de Brasília. Comissão Examinadora: ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Flávio René Kothe (Orientador) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Fernando Freitas Fuão Departamento de Teoria, História e Crítica da Arquitetura – FAU-UFRGS ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Lúcia Helena Marques Ribeiro Departamento de Teoria Literária e Literatura – TEL-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Ana Elisabete de Almeida Medeiros Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Benny Schvarsberg Departamento de Projeto e Planejamento – FAU-UnB Brasília – DF 2018 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a todos que compartilharam de alguma forma esse manifesto. Aos familiares que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança e o respeito. Aos amigos, colegas e alunos que dividiram as inquietações e os dias difíceis, agradeço a presença. Aos que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança. Aos professores, colegas e amigos do Núcleo de Estética, Hermenêutica e Semiótica. -

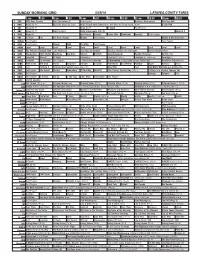

Sunday Morning Grid 5/29/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/29/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Nicklaus’ Masterpiece PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Senior PGA 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å Indy Pre-Race 2016 Indianapolis 500 (N) World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Marley & Me ››› (PG) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR The Patient’s Playbook With Leslie Michelson Easy Yoga for Arthritis Timeless Tractors: The Collectors Forever Wisdom-Dyer 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Aging Backwards Healthy Hormones Eat Fat, Get 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage The Inside Job. Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program La Rosa de Guadalupe El Barrendero (1982) Mario Moreno, María Sorté. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Formula One Racing Monaco Grand Prix.