Print, Munich, 1925), 178

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst Cornelis De Bie, Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst 244

Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst Cornelis de Bie bron Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst. Jan Meyssens, Juliaen van Montfort, Antwerpen 1662 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/bie_001guld01_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl 1 Het gulden cabinet vande edele vry schilder-const Ontsloten door den lanck ghevvenschten Vrede tusschen de twee mach- tighe Croonen van SPAIGNIEN EN VRANCRYCK, Waer-inne begrepen is den ontsterffe- lijcken loff vande vermaerste Constminnende Geesten ENDE SCHILDERS Van dese Eeuvv, hier inne meest naer het leven af-gebeldt, verciert met veel ver- makelijcke Rijmen ende Spreucken. DOOR Cornelis de Bie Notaris binnen Lyer. Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst 3 Den geboeyden Mars spreckt op d'uytleggingh van de titel plaet. WEl wijckt dan mijne Macht, en Raserny ter sijden? Moet mijne wreetheyt nu dees boose schant-vleck lijden? Dat ick hier ligh gheboyt en plat ter aert ghedruckt, Ontrooft van Sweert en Schilt, t'gen' my is af-geruckt? Alleen door liefdens kracht, die Vranckrijck heeft ontsteken, Die door het Echts verbont compt al mijn lusten breken, Die selffs de wreetheyt ben, wordt hier van liefd' gheplaegt, Den dullen Orloghs Godt wordt van den Peys verjaeght. Ach! d' Edel Fransche Trouw: (aen Spaenien verbonden:) Die heeft m' allendigh Helt in ballinckschap ghesonden. K' en heb niet eenen vriendt, men danckt my spoedigh aff Een jeder my verstoot, ick sien ick moet in't graff. Nochtans sal menich mensch mijn ongeluck beclaghen Die was ghewoon door my heel Belgica te plaeghen, Die was ghewoon met my te liggen op het landt Dat ick had uyt gheput door mijnen Orloghs brandt, De deught had ick verjaeght, en liefdens kracht ghenomen Midts dat mijn fury was in Neder-landt ghecomen Tot voordeel vanden Frans, die my nu brenght in druck En wederleyt mijn jonst, fortuyn en groot gheluck. -

The Arts Thrive Here

Illustrated THE ARTS THRIVE HERE Art Talks Vivian Gordon, Art Historian and Lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: REMEMBERING BIBLICAL WOMEN ARTISTS IN THEIR STUDIOS Monday, April 13, at 1PM Wednesday, May 20, at 1PM Feast your eyes on some of the most Depicting artists at work gives insight into the beautiful paintings ever. This illustrated talk will making of their art as well as their changing status examine how and why biblical women such as in society.This visual talk will show examples Esther, Judith, and Bathsheba, among others, from the Renaissance, the Impressionists, and were portrayed by the “Masters.” The artists Post-Impressionists-all adding to our knowledge to be discussed include Mantegna, Cranach, of the nature of their creativity and inspiration. Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt. FINE IMPRESSIONS: CAILLEBOTTE, SISLEY, BAZILLE Monday, June 15, at 1PM This illustrated lecture will focus on the work of three important (but not widely known) Impressionist painters. Join us as Ms. Gordon introduces the art, lives and careers of these important fi gures in French Impressionist art. Ines Powell, Art Historian and Educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: ALBRECHT DURER and HANS HOLBEIN the ELDER Thursday, April 23, at 1PM Unequaled in his artistic and technical execution of woodcuts and engravings, 16th century German artist Durer revolutionized the art world, exploring such themes as love, temptation and power. Hans Holbein the Elder was a German painter, a printmaker and a contemporary of Durer. His works are characterized by deep, rich coloring and by balanced compositions. -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart Kok, E.E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kok, E. E. (2013). Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Summary Jacob Backer (1608/9-1651), Govert Flinck (1615-1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), and Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) belong among the most successful portrait and history painters of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

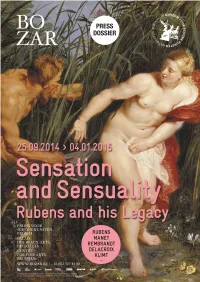

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

“The Concert” Oil on Canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ Ins., 105.5 by 133.5 Cms

Dirck Van Baburen (Wijk bij Duurstede, near Utrecht 1594/5 - Utrecht 1624) “The Concert” Oil on canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ ins., 105.5 by 133.5 cms. Dirck van Baburen was the youngest member of the so-called Utrecht Caravaggisti, a group of artists all hailing from the city of Utrecht or its environs, who were inspired by the work of the famed Italian painter, Caravaggio (1571-1610). Around 1607, Van Baburen entered the studio of Paulus Moreelse (1571- 1638), an important Utrecht painter who primarily specialized in portraiture. In this studio the fledgling artist probably received his first, albeit indirect, exposure to elements of Caravaggio’s style which were already trickling north during the first decade of the new century. After a four-year apprenticeship with Moreelse, Van Baburen departed for Italy shortly after 1611; he would remain there, headquartered in Rome, until roughly the summer of 1620. Caravaggio was already deceased by the time Van Baburen arrived in the eternal city. Nevertheless, his Italian period work attests to his familiarity with the celebrated master’s art. Moreover, Van Baburen was likely friendly with one of Caravaggio’s most influential devotees, the enigmatic Lombard painter Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622). Manfredi and Van Baburen were recorded in 1619 as living in the same parish in Rome. Manfredi’s interpretations of Caravaggio’s are profoundly affected Van Baburen as well as other members of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Van Baburen’s output during his Italian sojourn is comprised almost entirely of religious paintings, some of which were executed for Rome’s most prominent churches. -

The Petrifying Gaze of Medusa: Ambivalence, Ekplexis, and the Sublime

Volume 8, Issue 2 (Summer 2016) The Petrifying Gaze of Medusa: Ambivalence, Ekplexis, and the Sublime Caroline van Eck [email protected] Recommended Citation: Caroline van Eck, “The Sublime and the “The Petrifying Gaze of Medusa: Ambivalence, Ekplexis, and the Sublime,” JHNA 8:2 (Summer 2016), DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2016.8.2.3 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/petrifying-gaze-medusa-ambivalence-explexis-sublime/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 THE PETRIFYING GAZE OF MEDUSA: AMBIVALENCE, EKPLEXIS, AND THE SUBLIME Caroline van Eck The Dutch art theorists Junius and van Hoogstraten describe the sublime, much more explicitly and insistently than in Longinus’s text, as the power of images to petrify the viewer and to stay fixed in their memory. This effect can be related to Longinus’s distinction between poetry and prose. Prose employs the strategy of enargeia; poetry that of ekplexis, or shattering the listener or reader. This essay traces the notion of ekplexis in Greek rhetoric, particularly in Hermogenes, and shows the connections in etymology, myth, and pictorial traditions, between the petrifying powers of art and the myth of Medusa. DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2016.8.2.3 Introduction Fig. 1 Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), Medusa, ca. -

The Restorations of the Rietveld Schröderhuis

THE RESTORATIONS OF THE RIETVELD SCHRÖDERHUIS A REFLECTION Marie-Thérèse van Thoor The Netherlands World Heritage List currently num- Rietveld (1888-1964), a fame equal to that of Le Corbu- bers ten sites, most of which are related to water. The sier or Mies van der Rohe. In late 2015, a Keeping it exceptions are the Van Nelle Factory and the only pri- Modern Grant from the Getty Foundation enabled re- vate home on the list, the Rietveld Schröder House search to be carried out into the restorations of the (1924) in Utrecht. In 1987 the house opened as a muse- house in the 1970s and 1980s.1 Until now there have um and since 2013 it has been part of the collection of been only a few publications devoted to these resto- Utrecht’s Centraal Museum (fig. ).1 For the inhabitants rations, all personal accounts by the restoration archi- of the city the house is simply part of the Utrecht street- tect, Bertus Mulder (b. 1929).2 The new research project 15-31 PAGINA’S scape. But elsewhere in the world this one house (and made it possible to put these accounts on a scientific that one red-blue chair) earned its architect, Gerrit T. footing and to enrich them by means of extensive ar- chival research and oral history in the form of conver- m 1. The Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht, Unesco World sations with Mulder.3 Heritage monument since 2000, photo Stijn Poelstra 2018 The materialization of external and internal walls, in (Centraal Museum, Utrecht (CMU)) plaster- and paintwork played a key role in Rietveld’s 15 2. -

Colour, Form, and Space: Rietveld Schröder House Challenging The

COLOUR, FORM AND SPACE RIETVELD SCHRÖDER HOUSE CHALLENGING THE FUTURE Marie-Thérèse van Thoor [ed.] COLOUR, FORM AND SPACE TU Delft, in collaboration with Centraal Museum, Utrecht. This publication is made possible with support from the Getty Foundation as part of its Keeping It Modern initiative. ISBN 978-94-6366-145-4 © 2019 TU Delft No part of these pages, either text or image, may be used for any purpose other than research, academic or non-commercial use. The publisher has done its utmost to trace those who hold the rights to the displayed materials. COLOUR, FORM AND SPACE RIETVELD SCHRÖDER HOUSE CHALLENGING THE FUTURE Marie-Thérèse van Thoor [ed.] COLOUR, FORM AND SPACE / Rietveld Schröder House challenging the Future 4 Contents CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 7 Marie-Thérèse van Thoor THE RESTORATION OF THE EXTERIOR 11 Marie-Thérèse van Thoor THE PAINTWORK AND THE COLOURS OF THE EXTERIOR 23 Marie-Thérèse van Thoor RESTORATION OF THE INTERIOR 35 Marie-Thérèse van Thoor THE HOUSE OF TRUUS SCHRÖDER: FROM HOME TO MUSEUM HOUSE 55 Natalie Dubois INDOOR CLIMATE IN THE RIETVELD SCHRÖDER HOUSE 91 Barbara Lubelli and Rob van Hees EPILOGUE 101 ENDNOTES 105 LITERATURE 113 ARCHIVES 114 CONVERSATIONS 114 COLOPHON 117 5 COLOUR, FORM AND SPACE / Rietveld Schröder House challenging the Future INTRODUCTION MARIE-THÉRÈSE VAN THOOR 6 Introduction INTRODUCTION MARIE-THÉRÈSE VAN THOOR The Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht was designed in 1924 is also a milestone in the history of modern heritage restoration by Gerrit Thomas Rietveld (1888-1964) for Mrs Truus Schröder- and a manifesto for the concern for modern heritage in Schräder (1889-1985), as a home for her and her three young the Netherlands. -

Technical Art History Colloquium

TECHNICAL ART HISTORY COLLOQUIUM ‘The Calling of St. Matthew’ (1621) by Hendrick ter Brugghen. Centraal Museum, Utrecht The Technical Art History Colloquium is organised by Sven Dupré (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam, PI ERC ARTECHNE), Arjan de Koomen (University of Amsterdam, Coordinator MA Technical Art History) and Abbie Vandivere (Paintings conservator, Mauritshuis, The Hague & Vice-Program Director MA Technical Art History). Monthly meetings take place on Thursdays, alternately in Utrecht and Amsterdam. The fifth edition of the Technical Art History Colloquium will be held at the Centraal Museum Utrecht, in connection with the upcoming exhibition Caravaggio, Utrecht and Europe. Liesbeth M. Helmus (Curator of old masters, Centraal Museum Utrecht) will present preliminary results of technical research on paintings by Dirck van Baburen and Hendrick ter Brugghen. Marco Cardinali (Technical art historian at Emmebi Diagnostica Artistica, Rome and visiting professor at the Stockholm University and UNAM-Mexico City) will present — as co-editor and curator of the scientific research — the recently published Caravaggio. Works in Rome. Technique and Style (2016). The result of an ambitious project launched in 2009 and funded by the National Committee for the Celebrations of the Fourth Centenary of the Death of Caravaggio, this book sheds light on Caravaggio’s pictorial methods through technical research on twenty- two unquestionably original works in Rome. Date: September 22, 2016 Time: 14:00 – 16:00 (presentations) — 16:00 – 17:00 (possibility to visit the museum) Location: Centraal Museum, Agnietenstraat 1, Utrecht — Aula Admission free Caravaggio’s Painting Technique and the Art Critique. A Technical Art History Marco Cardinali The recently published book Caravaggio. -

Rembrandt's 1654 Life of Christ Prints

REMBRANDT’S 1654 LIFE OF CHRIST PRINTS: GRAPHIC CHIAROSCURO, THE NORTHERN PRINT TRADITION, AND THE QUESTION OF SERIES by CATHERINE BAILEY WATKINS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 ii This dissertation is dedicated with love to my children, Peter and Beatrice. iii Table of Contents List of Images v Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historiography 13 Chapter 2: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and the Northern Print Tradition 65 Chapter 3: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interest in Tone 92 Chapter 4: The Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus and Rembrandt’s Techniques for Producing Chiaroscuro 115 Chapter 5: Technique and Meaning in the Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus 140 Chapter 6: The Question of Series 155 Conclusion 170 Appendix: Images 177 Bibliography 288 iv List of Images Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Presentation in the Temple, c. 1654 178 Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1950.1508 Figure 2 Rembrandt, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654 179 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, P474 Figure 3 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 180 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.5 Figure 4 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 181 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1922.280 Figure 5 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 182 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.4 Figure 6 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 183 London, The British Museum, 1973,U.1088 Figure 7 Albrecht Dürer, St.