Unicode from a Linguistic Point of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York Statewide Data Warehouse Guidelines for Extracts for Use In

New York State Student Information Repository System (SIRS) Manual Reporting Data for the 2015–16 School Year October 16, 2015 Version 11.5 The University of the State of New York THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Information and Reporting Services Albany, New York 12234 Student Information Repository System Manual Version 11.5 Revision History Version Date Revisions Changes from 2014–15 to 2015–16 are highlighted in yellow. Changes since last version highlighted in blue. Initial Release. New eScholar template – Staff Attendance. CONTACT and STUDENT CONTACT FACTS fields for local use only. See templates at http://www.p12.nysed.gov/irs/vendors/2015- 16/techInfo.html. New Assessment Measure Standard, Career Path, Course, Staff Attendance, Tenure Area, and CIP Codes. New Reason for Ending Program Service code for students with disabilities: 672 – Received CDOS at End of School Year. Reason for Beginning Enrollment Code 5544 guidance revised. Reason for Ending Enrollment Codes 085 and 629 clarified and 816 modified. 11.0 October 1, 2015 Score ranges for Common Core Regents added in Standard Achieved Code section. NYSITELL has five performance levels and new standard achieved codes. Transgender student reporting guidance added. FRPL guidance revised. GED now referred to as High School Equivalency (HSE) diploma, language revised, but codes descriptions that contain “GED” have not changed. Limited English Proficient (LEP) students now referred to as English Language Learners (ELL), but code descriptions that contain “Limited English Proficient” or “LEP” have not changed. 11.1 October 8, 2015 Preschool/PreK/UPK guidance updated. 11.2 October 9, 2015 Tenure Are Code SMS added. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Synesthetes: a Handbook

Synesthetes: a handbook by Sean A. Day i © 2016 Sean A. Day All pictures and diagrams used in this publication are either in public domain or are the property of Sean A. Day ii Dedications To the following: Susanne Michaela Wiesner Midori Ming-Mei Cameo Myrdene Anderson and subscribers to the Synesthesia List, past and present iii Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction – What is synesthesia? ................................................... 1 Definition......................................................................................................... 1 The Synesthesia ListSM .................................................................................... 3 What causes synesthesia? ................................................................................ 4 What are the characteristics of synesthesia? .................................................... 6 On synesthesia being “abnormal” and ineffable ............................................ 11 Chapter 2: What is the full range of possibilities of types of synesthesia? ........ 13 How many different types of synesthesia are there? ..................................... 13 Can synesthesia be two-way? ........................................................................ 22 What is the ratio of synesthetes to non-synesthetes? ..................................... 22 What is the age of onset for congenital synesthesia? ..................................... 23 Chapter 3: From graphemes ............................................................................... 25 -

The Braille Font

This is le brailletex incl boxdeftex introtex listingtex tablestex and exampletex ai The Br E font LL The Braille six dots typ esetting characters for blind p ersons c comp osed by Udo Heyl Germany in January Error Reports in case of UNCHANGED versions to Udo Heyl Stregdaer Allee Eisenach Federal Republic of Germany or DANTE Deutschsprachige Anwendervereinigung T X eV Postfach E Heidelb erg Federal Republic of Germany email dantedantede Intro duction Reference The software is founded on World Brail le Usage by Sir Clutha Mackenzie New Zealand Revised Edition Published by the United Nations Educational Scientic and Cultural Organization Place de Fontenoy Paris FRANCE and the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapp ed Library of Congress Washington DC USA ai What is Br E LL It is a fontwhich can b e read with the sense of touch and written via Braille slate or a mechanical Braille writer by blinds and extremly eyesight disabled The rst blind fontanight writing co de was an eight dot system invented by Charles Barbier for the Frencharmy The blind Louis Braille created a six dot system This system is used in the whole world nowadays In the Braille alphab et every character consists of parts of the six dots basic form with tworows of three dots Numb er and combination of the dots are dierent for the several characters and stops numbers have the same comp osition as characters a j Braille is read from left to right with the tips of the forengers The left forenger lightens to nd out the next line -

Haptiread: Reading Braille As Mid-Air Haptic Information

HaptiRead: Reading Braille as Mid-Air Haptic Information Viktorija Paneva Sofia Seinfeld Michael Kraiczi Jörg Müller University of Bayreuth, Germany {viktorija.paneva, sofia.seinfeld, michael.kraiczi, joerg.mueller}@uni-bayreuth.de Figure 1. With HaptiRead we evaluate for the first time the possibility of presenting Braille information as touchless haptic stimulation using ultrasonic mid-air haptic technology. We present three different methods of generating the haptic stimulation: Constant, Point-by-Point and Row-by-Row. (a) depicts the standard ordering of cells in a Braille character, and (b) shows how the character in (a) is displayed by the three proposed methods. HaptiRead delivers the information directly to the user, through their palm, in an unobtrusive manner. Thus the haptic display is particularly suitable for messages communicated in public, e.g. reading the departure time of the next bus at the bus stop (c). ABSTRACT Author Keywords Mid-air haptic interfaces have several advantages - the haptic Mid-air Haptics, Ultrasound, Haptic Feedback, Public information is delivered directly to the user, in a manner that Displays, Braille, Reading by Blind People. is unobtrusive to the immediate environment. They operate at a distance, thus easier to discover; they are more hygienic and allow interaction in 3D. We validate, for the first time, in INTRODUCTION a preliminary study with sighted and a user study with blind There are several challenges that blind people face when en- participants, the use of mid-air haptics for conveying Braille. gaging with interactive systems in public spaces. Firstly, it is We tested three haptic stimulation methods, where the hap- more difficult for the blind to maintain their personal privacy tic feedback was either: a) aligned temporally, with haptic when engaging with public displays. -

Autism Ontario VOICE for Hearing Impaired

SPECIAL EDUCATION ADVISORY COMMITTEE REGULAR MEETING AGENDA FEBRUARY 17, 2021 George Wedge, Chair Deborah Nightingale Easter Seals Association for Bright Children Melanie Battaglia, Vice Chair Mary Pugh Autism Ontario VOICE for Hearing Impaired Geoffrey Feldman Glenn Webster Ontario Disability Coalition Ontario Assoc. of Families of Children Lori Mastrogiuseppe with Communication Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Disorders Tyler Munro Wendy Layton Integration Action for Inclusion Community Representative Representative TRUSTEE MEMBERS Lisa McMahon Angela Kennedy Community Representative Daniel Di Giorgio Nancy Crawford MISSION The Toronto Catholic District School Board is an inclusive learning community uniting home, parish and school and rooted in the love of Christ. We educate students to grow in grace and knowledge to lead lives of faith, hope and charity. VISION At Toronto Catholic we transform the world through witness, faith, innovation and action. Recording Secretary: Sophia Harris, 416-222-8282 Ext. 2293 Assistant Recording Secretary: Skeeter Hinds-Barnett, 416-222-8282 Ext. 2298 Assistant Recording Secretary: Sarah Pellegrini, 416-222-8282 Ext. 2207 Dr. Brendan Browne Joseph Martino Director of Education Chair of the Board Terms of Reference for the Special Education Advisory Committee (SEAC) The Special Education Advisory Committee (SEAC) shall have responsibility for advising on matters pertaining to the following: (a) Annual SEAC planning calendar; (b) Annual SEAC goals and committee evaluation; (c) Development and delivery of TCDSB Special Education programs and services; (d) TCDSB Special Education Plan; (e) Board Learning and Improvement Plan (BLIP) as it relates to Special Education programs, Services, and student achievement; (f) TCDSB budget process as it relates to Special Education; and (g) Public access and consultation regarding matters related to Special Education programs and services. -

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2005 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2005 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: ISO/IEC 10646-1 Second Edition text, Draft 2 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Working paper of JTC1/SC2/WG2 ACTION: For review and comment by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 1. Scope This paper provides a second draft of the text sections of the Second Edition of ISO/IEC 10646-1. It replaces the previous paper WG2 N 1796 (1998-06-01). This draft text includes: - Clauses 1 to 27 (replacing the previous clauses 1 to 26), - Annexes A to R (replacing the previous Annexes A to T), and is attached here as “Draft 2 for ISO/IEC 10646-1 : 1999” (pages ii & 1 to 77). Published and Draft Amendments up to Amd.31 (Tibetan extended), Technical Corrigenda nos. 1, 2, and 3, and editorial corrigenda approved by WG2 up to 1999-03-15, have been applied to the text. The draft does not include: - character glyph tables and name tables (these will be provided in a separate WG2 document from AFII), - the alphabetically sorted list of character names in Annex E (now Annex G), - markings to show the differences from the previous draft. A separate WG2 paper will give the editorial corrigenda applied to this text since N 1796. The editorial corrigenda are as agreed at WG2 meetings #34 to #36. Editorial corrigenda applicable to the character glyph tables and name tables, as listed in N1796 pages 2 to 5, have already been applied to the draft character tables prepared by AFII. -

LS2208 Product Reference Guide, P/N MN000754A02 Rev A

LS2208 PRODUCT REFERENCE GUIDE LS2208 PRODUCT REFERENCE GUIDE MN000754A02 Revision A March 2015 ii LS2208 Product Reference Guide No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form, or by any electrical or mechanical means, without permission in writing. This includes electronic or mechanical means, such as photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval systems. The material in this manual is subject to change without notice. The software is provided strictly on an “as is” basis. All software, including firmware, furnished to the user is on a licensed basis. We grant to the user a non-transferable and non-exclusive license to use each software or firmware program delivered hereunder (licensed program). Except as noted below, such license may not be assigned, sublicensed, or otherwise transferred by the user without our prior written consent. No right to copy a licensed program in whole or in part is granted, except as permitted under copyright law. The user shall not modify, merge, or incorporate any form or portion of a licensed program with other program material, create a derivative work from a licensed program, or use a licensed program in a network without our written permission. The user agrees to maintain our copyright notice on the licensed programs delivered hereunder, and to include the same on any authorized copies it makes, in whole or in part. The user agrees not to decompile, disassemble, decode, or reverse engineer any licensed program delivered to the user or any portion thereof. Zebra reserves the right to make changes to any product to improve reliability, function, or design. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Braille in Mathematics Education

Masters Thesis Information Sciences Radboud University Nijmegen Braille in Mathematics Education Marc Bitter April 4, 2013 Supervisors IK183 Prof.Dr.Ir. Theo van der Weide Dr. Henny van der Meijden Abstract This research project aimed to make improvements to the way blind learners in the Netherlands use mathematics in an educational context. As part of this research, con- textual research in the field of cognition, braille, education, and mathematics was con- ducted. In order to compare representations of mathematics in braille, various braille codes were compared according to set criteria. Finally, four Dutch mathematics curricula were compared in terms of cognitive complexity of the mathematical formulas required for the respective curriculum. For this research, two main research methods were used. A literature study was conducted for contextual information regarding cognitive aspects, historic information on braille, and the education system in the Netherlands. Interviews with experts in the field of mathematics education and braille were held to relate the contextual findings to practical issues, and to understand why certain decisions were made in the past. The main finding in terms of cognitive aspects, involves the limitation of tactile and auditory senses and the impact these limitations have on textual aspects of mathematics. Besides graphical content, the representation of mathematical formulas was found to be extremely difficult for blind learners. There are two main ways to express mathematics in braille: using a dedicated braille code containing braille-specific symbols, or using a linear translation of a pseudo-code into braille. Pseudo-codes allow for reading and producing by sighted users as well as blind users, and are the main approach for providing braille material to blind learners in the Netherlands. -

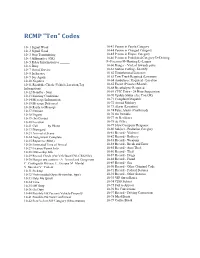

RCMP Ten Codes

RCMP "Ten" Codes 10- 1 Signal Weak 10-43 Person in Parole Category 10- 2 Signal Good 10-44 Person in Charged Category 10- 3 Stop Transmitting 10-45 Person in Elopee Category 10- 4 Affirmative (OK) 10-46 Person in Prohibited Category D=Driving 10- 5 Relay Information to ______ F=Firearms H=Hunting L=Liquor 10- 6 Busy 10-60 Danger - Violent towards police 10- 7 Out of Service 10-61 Station Calling - Identify 10- 8 In Service 10-62 Unauthorized Listeners 10- 9 Say Again 10-63 Tow Truck Required (Location) 10-10 Negative 10-64 Ambulance Required - Location 10-11 Roadside Check (Vehicle,Location,Tag 10-65 Escort (Prisoner/Mental) Information) 10-68 Breathalyzer Required 10-12 Standby - Stop 10-69 CPIC Entry - 24 Hour Suspension 10-13 Existing Conditions 10-70 Update Status (Are You OK) 10-14 Message/Information 10-71 Complaint Dispatch 10-15 Message Delivered 10-72 Armed Robbery 10-16 Reply to Message 10-73 Alarm (Location) 10-17 Enroute 10-74 False Alarm (Confirmed) 10-18 Urgent 10-76 On Portable 10-19 (In) Contact 10-77 At Residence 10-20 Location 10-78 At Office 10-21 Call _____ by Phone 10-79 Slow Computer Response 10-22 Disregard 10-80 Subject - Probation Category 10-23 Arrived at Scene 10-81 Record - Violence 10-24 Assignment Complete 10-82 Record - Robbery 10-25 Report to (Meet) 10-83 Record - Weapons 10-26 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-84 Record - Break and Enter 10-27 Licence/Permit Info 10-85 Record - Auto Theft 10-28 Ownership Info 10-86 Record - Theft 10-29 Record Check (Per/Veh/Boat/CNI-CRS File) 10-87 Record - Drugs 10-30 Danger -

Mountbatten Pro User Guide

User Guide Mountbatten Pro Revision 2 © Harpo Sp. z o. o. ul. 27 Grudnia 7, 61-737 Poznań, Poland www.mountbattenbrailler.com Thank you for purchasing a Mountbatten Pro. Since 1990, the Mountbatten range of Braille Writers has been offering expanded Braille writing opportunities to people all around the world. Mountbatten Braille Writers are in use in countries all over the world, bringing and supporting Braille literacy in many languages. To get the most from your new MB Pro, please read the first section, Welcome, and follow it with the second section, Exploring the MB Pro. After that, you can skip to the sections you want to read first, because you will have the most important basic information. News, resources, regular updates to this User Guide and a range of support material can be obtained from the Mountbatten website: www.mountbattenbrailler.com This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. Operation is subject to the following two conditions: (1) this device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference received, including interference that may cause undesired operation. Contents Welcome................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Reading your User Guide.................................................................................................................................. 1 Very Important!.................................................................................................................................................