Book Club Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Dissertation Workshop Finding Primary Source Material in Special

History Dissertation Workshop Finding primary source material in Special Collections General Up-to-date information about the Special Collections Department (collection descriptions, manuscripts search, opening hours, exhibitions pages, etc) is at: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/ You can navigate to the Special Collections homepage by selecting the Special Collections button at the foot of the library’s homepage. Useful resources on the Special Collections web pages Collection descriptions Each of the collections is described fully along with guidance about how to find material (including links to relevant catalogue records) at: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/collectionsa-z/ Browsing through these descriptions can help give you a ‘feel’ for the kind of material available in Special Collections, but use the subject index (follow link on left toolbar ‘Search by subject’) to ascertain which of the collections might be of most relevance to more specific topics: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/searchbysubject/ Collections that might be of particular interest for pre-modern history dissertations: • Chapbooks : recreational reading of the poor in 18th & 19th Centuries • Ferguson : includes substantial collection of witchcraft literature • Hunterian : wide ranging 18th century library (early books/medieval manuscripts) • J.S.C. : pamphlets, broadsides & books from 1690-99 • Murray : collection strong in west of Scotland regional history • Ogilvie : English civil war pamphlets • Smith (ephemera) -

Benefits of the Library Treasures Volume Considered

Making treasures pay? Benefits of the library treasures volume considered K. E. Attar Senate House Library University of London [email protected] The past decade has seen the publication of numerous treasures books relating to the holdings of libraries of various sizes across several sec- tors, with more in progress at the time of writing. These glossy tomes are not cheap to produce. Apart from up-front payment of publication costs, to be recouped through sales, there is the cost of photography and staff time: selecting items to be featured, identifying and liaising with contribu- tors, writing, editing and proof-reading. Why do it? Are we on a bandwagon, keeping pace with each other because the time has come when not to have produced a treasures volume may suggest a library’s paucity of rare, valuable or significant items? If the aim is to stake a claim about status and holdings, how meaningful will treasures volumes be when we all have them? How much do they really demonstrate now, when in a sense they are a leveller: if a treasures volume features, say, one hundred items, a library with 101 appro- priate candidates can produce one just as well as a library with ten thousand items from which to choose. While only time will test the long-term value of the treasures volume in raising a library’s profile, creating such a book can be a positive enterprise in numerous other ways. This article is based on the treasures volume produced by Senate House Library, University of London, in November 2012.1 It reflects on benefits Senate House Library has enjoyed by undertaking the project, in the hope that the sharing of one library’s experience may encourage others. -

LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE PUBLISHER PRICE CONDITION ? ? the Life of Fancis Covell E

LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE PUBLISHER PRICE CONDITION ? ? The Life of Fancis Covell E. Wilmshurst, Blackheath $15 poor to fair ? ? Good Housekeeping's Book of Meals Good Housekeepind $23 poor ? ? A Supreme Book for Girls Dean & Son $10 good ? ? Personal Hygiene for Every Man and Boy A Social Guidance Enterprises $13 fair Abbey J. Biggles in Spain Oxford University Press $13 good with d/c Abbot Willis The Nations at War Leslie-Judge Co. $35 fair to good Abbott Jacob Mary Queen of Scots Makers of History $12 good Adler Renata Gone Simon & Schuster $20 Excellent with d/c Ainsworth William The Tower of London W. Foulsham $20 fair Ainsworth W. H. Windsor Castle Collins $8 fair to good Ainsworth W. H. Old St. Paul's Collins $10 good Ainsworth William Rookwood George Routledge and Sons $13 good to excellent Ainsworth W. H. The Tower of London Collins $5 good to excellent Alcott Louisa May Little Men Whitman Publishing Company $10 good Alcott Louisa May Little Women Goldsmith $22 good Alcott Louisa May Eight Cousins Whitman Publishing Company $7 fair to good Alcott Louisa Rose in Bloom Whitman Publishing Company $15 poor Alcott Lousia Little Women Juvenile Productions $5 fair to good with d/c Alcott Louisa An Old-Fashion Girl Donohue $10 poor to fair Alcott Louisa Little Women Saalfield $18 fair Alger Horatio In a New World M. A. Donohue $12 fair Allen Hervey Anthony Adverse Farrar and Rinehart Inc. $115 fair to good Angel Henry Practical Plane and Solid Geomerty William Collins, Sons $5 fair Appleton Victor Tom Swift and His Giant Robot Grosset & Dunlap $5 good Aquith & Bigland C. -

Poems (1962-1997) 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

POEMS (1962-1997) 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Lax | 9781933517766 | | | | | Poems (1962-1997) 1st edition PDF Book Published by John Sharpe, London DJ a little nicked to corners of spine panel and with a little waving to leaves. Free In-store Pickup. Lax may be one of the rare poets whose work is better read Taken individually, the poems in this collection of Robert Lax's work are intriguing, combining radical simplicity with an almost meditative use of emptiness and space to offer a style that is utterly unique. Ex school library copy, only evidence marks on endpapers where sticker has been attached and some reference numbers, and stamp on back endpaper. Item added to your basket View basket. Sort: Best Match. Book in good to fair condition, it has a good clean text so it is easy to read, with natural wear with age. In stock, Ships from Ohio. Emily Dickinson Filter Applied. Got one to sell? Lax may be one of the rare poets whose work is better read in isolation than all together in one place. Grant us now an accompanying text! November, , pp. Gudrun Grabher, Ed. Published by The Book league of America Guaranteed Delivery see all. United Kingdom. No Preference. Collectible Manga in English. Completed Items. He was writing in columns instead of lines, again as the intro points out, and this--it seems to me--makes his poetry and its layout more a matter of music Certainly not everyone's cup of tea, and not my usual poetry leanings. Milne First Edition Hardcover Published by Wordsworth Editions, Limited We have , books to choose from -- Ship within 24 hours -- Satisfaction Guaranteed!. -

Lowney Turner Handy Library Collection (PDF)

Department of Special Collections Cunningham Memorial Library Indiana State University BOOKS FROM THE LOWNEY TURNER HANDY LIBRARY AT THE COLONY List Prepared & Edited by David Vancil June 8, 2001 / Rev. July 30, 2001 / April 26, 2002 Lowney Turner Handy, writing teacher of James Jones and others, maintained a writing school in southern Illinois. Her teaching approach included the use of various works from her library which students had to read and copy by hand or by using a typewriter in the process of becoming familiar with accomplished writing styles. Most of the books listed below are fiction and poetry, although an occasional title in a different realm is also included. Many of the books are annotated by Handy with comments, sometimes on the pastedown, sometimes in the body of the work.. A few items, notably his own works, were gifts from James Jones. Also included in the collection are published works of other successful students, e.g., Jere Peacock., Tom Chamales, and Edwin Daly. These books were about to be discarded when Elizabeth Bevington, an antiquarian bookseller and member of the Friends of the Cunningham Memorial Library, retrieved them and donated them to the library as the Lowney Turner Handy Library Collection to be housed within the Rare Books Collection. List of Donated Books Acworth, Bernard. Swift. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1947. Rare Books PR3726.A58 1947s. Dinesen, Isak. The Angelic Avengers by Pierre Andrézel. New York: Random House, 1947. Rare Books PT8175.B545 G43 1947s. Arlen, Michael. The Flying Dutchman: A Novel. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1939. Rare Books PR6001.R7 F6 1939s. -

Inquiry: a Study of Continuous Improvement (2Nd Edition)

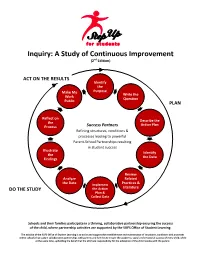

Inquiry: A Study of Continuous Improvement (2nd Edition) ACT ON THE RESULTS Identify the Make My Purpose Write the Work Question Public PLAN Reflect on Describe the the Action Plan Process Success Partners Refining structures, conditions & processes leading to powerful Parent-School Partnerships resulting in student success Illustrate Identify the the Data Findings Review Analyze Related the Data Implement Practices & Literature DO THE STUDY the Action Plan & Collect Data Schools and their families participate in a thriving, collaborative partnership ensuring the success of the child, where partnership activities are supported by the SUFS Office of Student Learning. The mission of the SUFS Office of Student Learning is to assist and support the establishment and maintenance of structures, conditions and processes within schools that sustain collaborative partnerships with parents and families to ensure the academic, social and emotional success of every child; while at the same time, upholding the belief that the ultimate responsibility for the education of the child resides with the parent. Table of Contents Welcome from Dr. Carol Thomas 1 What is Inquiry? 3 Identify the Purpose PLAN 8 Write and Refine the Question(s) PLAN 9 Describe the Action Plan PLAN 10 Identify the Data PLAN 11 Review Related Practices and Literature PLAN 13 Implement the Action Plan and Collect Data DO THE STUDY 14 Analyze the Data DO THE STUDY 15 Illustrate the Findings DO THE STUDY 16 Reflect on the Process ACT ON THE RESULTS 17 Preparing to Make My Work Public -

Book of the Month 1

ADL’s Book of the Month 1 Book of the Month Presented by ADL’s Education Department About the Book of the Month: This collection of featured books is from Books Matter: The Best Kid Lit on Bias, Diversity and Social Justice. The books teach about bias and prejudice, promote respect for diversity, encourage social action and reinforce themes addressed in education programs of A World of Difference® Institute, ADL's international anti-bias education and diversity training provider. For educators, adult family members and other caregivers of children, reading the books listed on this site with your children and incorporating them into instruction are excellent ways to talk about these important concepts at home and in the classroom. The Undefeated Kwame Alexander (Author), Kadir Nelson (Illustrator) This poetic picture book is a love letter to Black life and people in the United States. It highlights the unspeakable trauma of slavery, the faith and fire of the civil rights movement, and the passion, and perseverance of some of the world's greatest heroes. The text is also peppered with references to the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and others, offering deeper insights into the accomplishments of the past, while bringing stark attention to the endurance and spirit of Black people surviving and thriving in the present. ISBN: 978-1328780966 Publisher: Versify Year Published: 2019 Age Range: 6–9 Book Themes Black History, History of Racism, Civil Rights, Race, Racism, Courage and Persistence Key Words Discuss and define these words with children prior to reading the book. -

000 Computer Science, Information, General Works

000 000 Computer science, information, general works SUMMARY 001–006 [Knowledge, the book, systems, computer science] 010 Bibliography 020 Library and information sciences 030 General encyclopedic works 050 General serial publications 060 General organizations and museology 070 Documentary media, educational media, news media; journalism; publishing 080 General collections 090 Manuscripts, rare books, other rare printed materials 001 Knowledge Description and critical appraisal of intellectual activity in general Including interdisciplinary works on consultants Class here discussion of ideas from many fields; interdisciplinary approach to knowledge Class epistemology in 121. Class a compilation of knowledge in a specific form with the form, e.g., encyclopedias 030 For consultants or use of consultants in a specific subject, see the subject, e.g., library consultants 023, engineering consultants 620, use of consultants in management 658.4 See Manual at 500 vs. 001 .01 Theory of knowledge Do not use for philosophy of knowledge, philosophical works on theory of knowledge; class in 121 .1 Intellectual life Nature and value For scholarship and learning, see 001.2 See also 900 for broad description of intellectual situation and condition 217 001 Dewey Decimal Classification 001 .2 Scholarship and learning Intellectual activity directed toward increase of knowledge Class methods of study and teaching in 371.3. Class a specific branch of scholarship and learning with the branch, e.g., scholarship in the humanities 001.3, in history 900 For research, -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids And

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids and Services Available to the Blind and Visually Handicapped. First Edition. INSTITUTION Delta Gamma Foundation, Columbus, Ohio. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 44p.; (0 References) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Blind; Braille; Childrer.; Large Type Materials; Library Materials; *Library Services; *Partially Sighted; Senior Citizens; Talking Books; *Visually Handicapped ABSTRACT The information contained in this publication will be helpful in carrying out projects to aid blind and visually handicapped children and adults of all ages. Special materials available from the Library of Congress such as: talking books, books in braille, large print books, and books in moon tkpe are described. Other sources of reading materials for the blind ard partially sighted are listed, as are the magazines for the blind and partially sighted. Also included are cookbooks, and knitting and crocheting books for the blind and partially sighted. Sources of reading aids and supplies are listed and suggestions for giving personalized help to these handicapped persons are included. ()uthor/NH) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEH REPRO. DUCE() EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG. INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN. IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF ECIU. CATION POSITION OR POUCY. LIBRARY AIDS AND SERVICES AVAILABLE TO THE BLIND AND VISUALLY HANDICAPPEDr This book was produced and printed in be Delta -

Clyde Edgerton Thomas S

Clyde Edgerton Thomas S. Kenan III Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing PhD, MAT, BA, UNC Chapel Hill Guggenheim Fellowship Lyndhurst Prize Honorary Doctorates from UNC-Asheville and St. Andrews Presbyterian College Fellowship of Southern Writers the North Carolina Award for Literature five notable book awards from the New York Times “Mr. Edgerton’s ability to shine a clear, warm light on the dark things of life without becoming sugary makes a vivid backdrop for his tolerant humor and his alertness to the human genius for nonsense.” —The New Yorker Clyde Edgerton is the author of ten novels, a book of advice, a memoir, short stories, and essays. Three of his novels have been made into movies: Raney, Walking Across Egypt, and Killer Diller. Edgerton’s short stories and essays have been published in New York Times Magazine, Best American Short Stories, Southern Review, Oxford American, Garden & Gun and other publications. Rebecca Lee associate professor MFA, University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop BA, St. Olaf College Danuta Gleed Literary Award, 2012 National Magazine Award, for “Fialta,” 2001 Bunting Fellowship, Harvard University, 2001-2002 Michener Fellowship, Iowa Writers Workshop, 1997 Rebecca Lee is the author of Bobcat and The City Is a Rising Tide. Her stories have been published in the Atlantic Monthly and Zoetrope, and she was the winner of the National Magazine Award for Fiction “Lee writes with an unflinching eye toward for “Fialta.” Her fiction has also been read on NPR’s the darkest and saddest aspects of life, often -

Images of International Relations

PART I Images of International Relations MM02_VIOT0000_05_SE_CH02.indd02_VIOT0000_05_SE_CH02.indd 3377 330/12/100/12/10 11:00:00 PPMM MM02_VIOT0000_05_SE_CH02.indd02_VIOT0000_05_SE_CH02.indd 3388 330/12/100/12/10 11:00:00 PPMM CHAPTER 2 Realism: The State and Balance of Power MAJOR ACTORS AND ASSUMPTIONS R ealism is an image of international relations based on four principal assumptions. Scholars or policymakers who identify themselves as realists, of course, do not all perfectly match the realism ideal type. We find, however, that the four assumptions identified with this perspective are useful as a general statement of the main lines of realist thought and the basis on which hypotheses and theories are developed. First, states are the principal or most important actors in an anarchical world lack- ing central legitimate governance. States represent the key units of analysis , whether one is dealing with ancient Greek city-states or modern nation-states. The study of international relations is the study of relations among these units, particularly major powers as they shape world politics (witness the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War) and engage in the costliest wars (World Wars I and II). Realists who use the concept of system usually refer to an international system of states. What of non-state actors? International organizations such as the United Nations may aspire to the status of independent actor, but from the realist perspective, this aspiration has not in fact been achieved to any significant degree. Realists tend to see international organizations as doing no more than their member states direct. -

INFO 6150: History of the Book Winter 2019 Thursdays, 8:35Pm-11:25Pm 2107 Mona Campbell Building

INFO 6150: History of the Book Winter 2019 Thursdays, 8:35pm-11:25pm 2107 Mona Campbell Building Instructor: Jennifer Grek Martin email: [email protected] Office: Rowe 4028 Office hours: 12:00 – 2:00pm Wednesdays, or by appt. Telephone: 902 494 2462 Note: the syllabus may be subject to minor changes before and/or throughout the term. Course Description: The History of the Book encompasses the study of book and print culture from Antiquity to the present, with emphasis on the Western world. This field is anything but stodgy; book and print history is a vibrant and fascinating discipline and this course will refract this intellectual excitement through reading and discussion of recent relevant research. Throughout the course, students will investigate shifts from orality to literacy, from writing to printing, and finally from analog to digital media. The creation, production, distribution, and reception of books, serials, and ephemera will be discussed, and aspects of humanities and scientific scholarship will be explored in relation to the development of the history of book and print culture. Course Pre-Requisites: none. Learning Objectives: ~ To introduce students to the study of book and print culture and to survey the literature and scholarship of this field. ~ To discuss and evaluate the theoretical models for the study of both print and digital culture. ~ To provide intellectual and historical context for the history of books and print culture for information managers and professionals. Learning Objectives: With successful completion of this course, students should be able to… I. Explain the processes of book creation, production, dissemination, and reception – through various media – through different cultural, social-economic, and political contexts over time.