Benefits of the Library Treasures Volume Considered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Dissertation Workshop Finding Primary Source Material in Special

History Dissertation Workshop Finding primary source material in Special Collections General Up-to-date information about the Special Collections Department (collection descriptions, manuscripts search, opening hours, exhibitions pages, etc) is at: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/ You can navigate to the Special Collections homepage by selecting the Special Collections button at the foot of the library’s homepage. Useful resources on the Special Collections web pages Collection descriptions Each of the collections is described fully along with guidance about how to find material (including links to relevant catalogue records) at: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/collectionsa-z/ Browsing through these descriptions can help give you a ‘feel’ for the kind of material available in Special Collections, but use the subject index (follow link on left toolbar ‘Search by subject’) to ascertain which of the collections might be of most relevance to more specific topics: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/searchbysubject/ Collections that might be of particular interest for pre-modern history dissertations: • Chapbooks : recreational reading of the poor in 18th & 19th Centuries • Ferguson : includes substantial collection of witchcraft literature • Hunterian : wide ranging 18th century library (early books/medieval manuscripts) • J.S.C. : pamphlets, broadsides & books from 1690-99 • Murray : collection strong in west of Scotland regional history • Ogilvie : English civil war pamphlets • Smith (ephemera) -

Inquiry: a Study of Continuous Improvement (2Nd Edition)

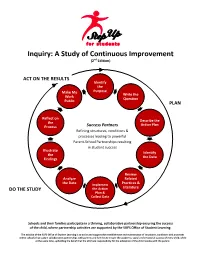

Inquiry: A Study of Continuous Improvement (2nd Edition) ACT ON THE RESULTS Identify the Make My Purpose Write the Work Question Public PLAN Reflect on Describe the the Action Plan Process Success Partners Refining structures, conditions & processes leading to powerful Parent-School Partnerships resulting in student success Illustrate Identify the the Data Findings Review Analyze Related the Data Implement Practices & Literature DO THE STUDY the Action Plan & Collect Data Schools and their families participate in a thriving, collaborative partnership ensuring the success of the child, where partnership activities are supported by the SUFS Office of Student Learning. The mission of the SUFS Office of Student Learning is to assist and support the establishment and maintenance of structures, conditions and processes within schools that sustain collaborative partnerships with parents and families to ensure the academic, social and emotional success of every child; while at the same time, upholding the belief that the ultimate responsibility for the education of the child resides with the parent. Table of Contents Welcome from Dr. Carol Thomas 1 What is Inquiry? 3 Identify the Purpose PLAN 8 Write and Refine the Question(s) PLAN 9 Describe the Action Plan PLAN 10 Identify the Data PLAN 11 Review Related Practices and Literature PLAN 13 Implement the Action Plan and Collect Data DO THE STUDY 14 Analyze the Data DO THE STUDY 15 Illustrate the Findings DO THE STUDY 16 Reflect on the Process ACT ON THE RESULTS 17 Preparing to Make My Work Public -

Book of the Month 1

ADL’s Book of the Month 1 Book of the Month Presented by ADL’s Education Department About the Book of the Month: This collection of featured books is from Books Matter: The Best Kid Lit on Bias, Diversity and Social Justice. The books teach about bias and prejudice, promote respect for diversity, encourage social action and reinforce themes addressed in education programs of A World of Difference® Institute, ADL's international anti-bias education and diversity training provider. For educators, adult family members and other caregivers of children, reading the books listed on this site with your children and incorporating them into instruction are excellent ways to talk about these important concepts at home and in the classroom. The Undefeated Kwame Alexander (Author), Kadir Nelson (Illustrator) This poetic picture book is a love letter to Black life and people in the United States. It highlights the unspeakable trauma of slavery, the faith and fire of the civil rights movement, and the passion, and perseverance of some of the world's greatest heroes. The text is also peppered with references to the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and others, offering deeper insights into the accomplishments of the past, while bringing stark attention to the endurance and spirit of Black people surviving and thriving in the present. ISBN: 978-1328780966 Publisher: Versify Year Published: 2019 Age Range: 6–9 Book Themes Black History, History of Racism, Civil Rights, Race, Racism, Courage and Persistence Key Words Discuss and define these words with children prior to reading the book. -

000 Computer Science, Information, General Works

000 000 Computer science, information, general works SUMMARY 001–006 [Knowledge, the book, systems, computer science] 010 Bibliography 020 Library and information sciences 030 General encyclopedic works 050 General serial publications 060 General organizations and museology 070 Documentary media, educational media, news media; journalism; publishing 080 General collections 090 Manuscripts, rare books, other rare printed materials 001 Knowledge Description and critical appraisal of intellectual activity in general Including interdisciplinary works on consultants Class here discussion of ideas from many fields; interdisciplinary approach to knowledge Class epistemology in 121. Class a compilation of knowledge in a specific form with the form, e.g., encyclopedias 030 For consultants or use of consultants in a specific subject, see the subject, e.g., library consultants 023, engineering consultants 620, use of consultants in management 658.4 See Manual at 500 vs. 001 .01 Theory of knowledge Do not use for philosophy of knowledge, philosophical works on theory of knowledge; class in 121 .1 Intellectual life Nature and value For scholarship and learning, see 001.2 See also 900 for broad description of intellectual situation and condition 217 001 Dewey Decimal Classification 001 .2 Scholarship and learning Intellectual activity directed toward increase of knowledge Class methods of study and teaching in 371.3. Class a specific branch of scholarship and learning with the branch, e.g., scholarship in the humanities 001.3, in history 900 For research, -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids And

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids and Services Available to the Blind and Visually Handicapped. First Edition. INSTITUTION Delta Gamma Foundation, Columbus, Ohio. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 44p.; (0 References) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Blind; Braille; Childrer.; Large Type Materials; Library Materials; *Library Services; *Partially Sighted; Senior Citizens; Talking Books; *Visually Handicapped ABSTRACT The information contained in this publication will be helpful in carrying out projects to aid blind and visually handicapped children and adults of all ages. Special materials available from the Library of Congress such as: talking books, books in braille, large print books, and books in moon tkpe are described. Other sources of reading materials for the blind ard partially sighted are listed, as are the magazines for the blind and partially sighted. Also included are cookbooks, and knitting and crocheting books for the blind and partially sighted. Sources of reading aids and supplies are listed and suggestions for giving personalized help to these handicapped persons are included. ()uthor/NH) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEH REPRO. DUCE() EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG. INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN. IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF ECIU. CATION POSITION OR POUCY. LIBRARY AIDS AND SERVICES AVAILABLE TO THE BLIND AND VISUALLY HANDICAPPEDr This book was produced and printed in be Delta -

Clyde Edgerton Thomas S

Clyde Edgerton Thomas S. Kenan III Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing PhD, MAT, BA, UNC Chapel Hill Guggenheim Fellowship Lyndhurst Prize Honorary Doctorates from UNC-Asheville and St. Andrews Presbyterian College Fellowship of Southern Writers the North Carolina Award for Literature five notable book awards from the New York Times “Mr. Edgerton’s ability to shine a clear, warm light on the dark things of life without becoming sugary makes a vivid backdrop for his tolerant humor and his alertness to the human genius for nonsense.” —The New Yorker Clyde Edgerton is the author of ten novels, a book of advice, a memoir, short stories, and essays. Three of his novels have been made into movies: Raney, Walking Across Egypt, and Killer Diller. Edgerton’s short stories and essays have been published in New York Times Magazine, Best American Short Stories, Southern Review, Oxford American, Garden & Gun and other publications. Rebecca Lee associate professor MFA, University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop BA, St. Olaf College Danuta Gleed Literary Award, 2012 National Magazine Award, for “Fialta,” 2001 Bunting Fellowship, Harvard University, 2001-2002 Michener Fellowship, Iowa Writers Workshop, 1997 Rebecca Lee is the author of Bobcat and The City Is a Rising Tide. Her stories have been published in the Atlantic Monthly and Zoetrope, and she was the winner of the National Magazine Award for Fiction “Lee writes with an unflinching eye toward for “Fialta.” Her fiction has also been read on NPR’s the darkest and saddest aspects of life, often -

INFO 6150: History of the Book Winter 2019 Thursdays, 8:35Pm-11:25Pm 2107 Mona Campbell Building

INFO 6150: History of the Book Winter 2019 Thursdays, 8:35pm-11:25pm 2107 Mona Campbell Building Instructor: Jennifer Grek Martin email: [email protected] Office: Rowe 4028 Office hours: 12:00 – 2:00pm Wednesdays, or by appt. Telephone: 902 494 2462 Note: the syllabus may be subject to minor changes before and/or throughout the term. Course Description: The History of the Book encompasses the study of book and print culture from Antiquity to the present, with emphasis on the Western world. This field is anything but stodgy; book and print history is a vibrant and fascinating discipline and this course will refract this intellectual excitement through reading and discussion of recent relevant research. Throughout the course, students will investigate shifts from orality to literacy, from writing to printing, and finally from analog to digital media. The creation, production, distribution, and reception of books, serials, and ephemera will be discussed, and aspects of humanities and scientific scholarship will be explored in relation to the development of the history of book and print culture. Course Pre-Requisites: none. Learning Objectives: ~ To introduce students to the study of book and print culture and to survey the literature and scholarship of this field. ~ To discuss and evaluate the theoretical models for the study of both print and digital culture. ~ To provide intellectual and historical context for the history of books and print culture for information managers and professionals. Learning Objectives: With successful completion of this course, students should be able to… I. Explain the processes of book creation, production, dissemination, and reception – through various media – through different cultural, social-economic, and political contexts over time. -

Book Clubs and Book Commerce

NORRICK-RÜHL In the twentieth century, cumulative millions of readers received books by mail from clubs like the Book-of-the- Month Club, the Book Society or Bertelsmann Club. This Book Clubs and Element o ers an introduction to book clubs as a distribution channel and cultural phenomenon and shows that book clubs Book Commerce and book commerce are linked inextricably. It argues that a global perspective is necessary to understand the cultural and economic impact of book clubs in the twentieth and into the twenty- rst centuries. It also explores central reasons for book club membership, condensing them into four succinct categories: convenience, community, concession and most importantly curation. Book Clubs and Commerce This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. Cambridge Elements in Publishing and Book Culture S E: Samantha Rayner University College London A E: Rebecca Lyons University of Bristol Publishing and Book Culture Bookshops and Bookselling ISSN 2514-8524 (online) ISSN 2514-8516 (print) Corinna Norrick-Rühl Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Johannes Gutenberg University, on 04 Mar 2020 at 11:23:54, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108597258 Elements in Publishing and Book Culture edited by Samantha Rayner University College London Rebecca Lyons University of Bristol BOOK CLUBS AND BOOK COMMERCE Corinna Norrick-Rühl Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Johannes Gutenberg University, on 04 Mar 2020 at 11:23:54, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

Dan Torday CV

6/30/21 Daniel Torday ________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Master Of Fine Arts in Creative Writing, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, 2007. Bachelor of Arts in English, Kenyon College, Gambier, OH. Magna Cum Laude. 2000. PUBLICATIONS FICTION Books: Boomer1. Novel. Hardcover. New York, NY. St. Martin’s Press. Fall 2018. Kirkus Best Fiction of 2018. Longlisted for the 2020 Simpson/Joyce Carol Oates Literary Prize. Feature film adaptation in development by End Cue production. Director Tamar Glezerman. Paperback. September 2019. New York, NY, Picador Books. The Last Flight of Poxl West. Novel. Hardcover. New York, NY. St. Martin’s Press, 2015. 291 pages. Winner of the 2017 Sami Rohr Choice Prize and the 2015 National Jewish Book Award for Fiction. New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. Finalist for the Wallant Award. Longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award. Amazon.com Best Debuts of 2015. Paperback. March 2016. New York, NY. Picador, 2016. 300 pages. French, Spanish, Japanese and Czech language editions. The Sensualist. Novella. Los Angeles, CA. Nouvella Books, 2012. 177 pages. Winner of the 2012 National Jewish Book Award for Outstanding Debut Fiction, the 2013 Goldberg Prize. Short Stories: Harvard Review. “A Guide For the Perplexed.” Issue 57. 2021. Guernica. “All Your Fathers All Your Brothers All Your Sons and Their Sons.” December 2020. 1 Conjunctions. “Neighbor.” Short Story. Spring 2019. Selected as Best American Short Stories 2020 Distinguished story. “You Are Traffic.” Short Story. Spring 2018. Tin House. “Nate Gertzman Draws the Internet.” Short Story. 68. Winter 2016. Selected as Best American Short Stories 2017 Distinguished story. n+1. “ECKEETA.” Short story. -

A World of Its Own 1St Edition Ebook

A WORLD OF ITS OWN 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matt Garci´a | 9780807898932 | | | | | A World of Its Own 1st edition PDF Book Putnam and Company. Helena St. The venture into children's book publishing proved quite successful. In , there were , people enrolled in college. Bibliographies can also address broader subjects. That indicates that the copy they are offering is the earliest example of that commercial production. Counter intuitively, a 1 in the number line for that publisher during those years meant a later printing. The first edition, published in has one ending, which is quite melancholy. That practice applies to all the publishing house's imprints, such as Bantam, Black Swan, Corgi, and Doubleday. This edition published year by Pan Books Ltd. For major publications that are reprinted annually, the date is omitted from the title page. The first American book club as we think of the groups today was formed in , in Mattoon, Illinois. Doubleday Since its inception in , Doubleday has been a powerful presence in the American publishing landscape. If reprintings include new copyrighted material, there will be a new copyright date as well as the original copyright year. Knopf published the magazine until If you are unfamiliar with the grading scale for book conditions you can find it on our used books page. The publishers avoid using the term "second edition" unless there is material difference from the first edition. Nothing would distinguish the Book Club editions from the trade editions. Doran Company in October 22, Biblio is open and shipping orders. But this is the exception, rather than the rule. -

Identifying First Editions (Updated 2018) the Table Below Lists the First Trade

Identifying first editions (updated 2018) Compiled by Bev Vincent with the assistance of materials made available by Rich DeMars, John Mastrocco, Steve Oelrich and Shaun Nauman. E-mail corrections or questions to [email protected] The table below lists the first trade edition identification criteria for each of Stephen King's books. The early Doubleday books all say "First Edition" explicitly on the copyright page (CP). There are other identifiers for these books as well. For books that contain strings of numbers to denote the printing, the important consideration is the presence of the numeral 1 in that string, regardless of the format of the numbers. Some possible variations of the printing numbers are: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All three of these denote a first edition. The numeral 1 will be removed for a second printing. Black House is the exception. First edition copies state "First Edition" on the copyright page and the number sequence will be "2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3". Trim size is given because Book Club editions are often smaller than trade editions. Also, Book Club edition dust jackets (DJ) are occasionally found on first editions to replace lost or damaged jackets. Book Club edition dust jackets are easily identified because they do not have a price marked inside the front cover. Later printing trade edition dust jackets will often have a different price from what is found in the table. -

Book of the Month 1

ADL’s Book of the Month 1 Book of the Month Presented by ADL’s Education Department About the Book of the Month: This collection of featured books is from Books Matter: The Best Kid Lit on Bias, Diversity and Social Justice. The books teach about bias and prejudice, promote respect for diversity, encourage social action and reinforce themes addressed in education programs of A World of Difference® Institute, ADL's international anti-bias education and diversity training provider. For educators, adult family members and other caregivers of children, reading the books listed on this site with your children and incorporating them into instruction are excellent ways to talk about these important concepts at home and in the classroom. Equality’s Call: The Story of Voting Rights in America Deborah Diesen (Author), Magdalena Mora (Illustrator) The founders of the United States declared that consent of the governed was a key part of their plan for the new nation. But for many years, only white men who had money could vote. This unflinching and inspiring history of voting rights looks back at the activists who answered equality’s call, working tirelessly to secure the right for all to vote, and it also looks forward to the future and the work that still needs to be done. ISBN: 978-1534439580 Publisher: Beach Lane Books Year Published: 2020 Age Range: 5–9 Book Themes Voting Rights, Equity, Racism, Sexism, Bias, Social Justice Key Words Discuss and define these words with children prior to reading the book. Do not focus on students’ retention of all the words; instead make sure they understand the words enough to follow the story and remind children of the words’ meanings as they come up in the book.