Akademik Hassasiyetler the Academic Elegance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

Relief and Rehabilitation Network Network Paper 4

Relief and Rehabilitation Network Network Paper 4 Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant September 1994 Please send comments on this paper to: Relief and Rehabilitation Network Overseas Development Institute Regent's College Inner Circle Regent's Park London NW1 4NS United Kingdom A copy will be sent to the author. Comments received may be used in future Newsletters. ISSN: 1353-8691 © Overseas Development Institute, London, 1994. Photocopies of all or part of this publication may be made providing that the source is acknowledged. Requests for commercial reproduction of Network material should be directed to ODI as copyright holders. The Network Coordinator would appreciate receiving details of any use of this material in training, research or programme design, implementation or evaluation. Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant1 Contents Page Maps 1. Introduction 1 2. Pride and Prejudice in the Somali Region 5 : The Political History of a Conflict 3 * The Ethiopian empire-state and the colonial powers 4 * Greater Somalia, Britain and the growth of Somali nationalism 8 * Conflict and war between Ethiopia and Somalia 10 * Civil war in Somalia 11 * The Transitional Government in Ethiopia and Somali Region 5 13 3. Cycles of Relief and Rehabilitation in Eastern Ethiopia : 1973-93 20 * 1973-85 : `Relief shelters' or the politics of drought and repatriation 21 * 1985-93 : Repatriation as opportunity for rehabilitation and development 22 * The pastoral sector : Recovery or control? 24 * Irrigation schemes : Ownership, management and economic viability 30 * Food aid : Targeting, free food and economic uses of food aid 35 * Community participation and institutional strengthening 42 1 Koenraad Van Brabant has been project manager relief and rehabilitation for eastern Ethiopia with SCF(UK) and is currently Oxfam's country representative in Sri Lanka. -

Vegetable Trade Between Self-Governance and Ethnic Entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gebresenbet, Fana Working Paper Perishable state-making: Vegetable trade between self-governance and ethnic entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia DIIS Working Paper, No. 2018:1 Provided in Cooperation with: Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen Suggested Citation: Gebresenbet, Fana (2018) : Perishable state-making: Vegetable trade between self-governance and ethnic entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia, DIIS Working Paper, No. 2018:1, ISBN 978-87-7605-911-8, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/179454 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under -

Afar: Insecurity and Delayed Rains Threaten Livestock and People

EMERGENCIES UNIT FOR UNITED NATIONS ETHIOPIA (UN-EUE) Afar: insecurity and delayed rains threaten livestock and people Assessment Mission: 29 May – 8 June 2002 François Piguet, Field Officer, UN-Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia 1 Introduction and background 1.1 Animals are now dying The Objectives of the mission were to assess the situation in the Afar Region following recent clashes between Afar and Issa and Oromo pastoralists, and focus on security and livestock movement restrictions, wate r and environmental issues, the marketing of livestock as well as “chronic” humanitarian issues. Special attention has been given to all southern parts of Afar region affected by recent ethnic conflicts and erratic small rains, which initiated early pastoralists movements in zone 3 & 5. The assessment also took into account various food security issues, including milk availability while also looking at limited water resources in Eli Daar woreda (Zone 1), where particularly remote kebeles1 suffer from water shortage. High concentrations of animals have been noticed in several locations of Afar region during the current dry season. The most important reason for the present humanitarian emergency crisis in parts of Afar Region and surroundings are the various ethnic conflicts among the Issa, the Kereyu, the Afar and the Ittu. These Dead camel in Doho, Awash-Fantale (photo Francois Piguet conflicts forced pastoralists to change UN-EUE, July 2002 their usual migration patterns and most importantly were denied access to either traditional water points and wells or grazing areas or both together. On top of this rather complex and confuse conflict situation, rains have now been delayed by more than two weeks most likely all over Afar Region and is now causing livestock deaths. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Social Organization and Cultural Institutions of the Afar of Northern Ethiopia

International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology Vol. 3(11), pp. 423-429, November 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJSA ISSN 2006-988x ©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Social organization and cultural institutions of the Afar of Northern Ethiopia Kelemework Tafere Reda Social Anthropology, Mekelle University, P. O. Box 175, Mekelle, Ethiopia. E-mail: [email protected]. Fax: 251 344 407610. Accepted 1 June, 2011 An anthropological study was conducted on the social organizations and traditional cultural institutions of the Afar pastoral society in northern Ethiopia. This paper describes the clan-based institutions that are central to Afar culture and cosmology. Gerontocracy (the rule of elders), well established economic and political support networks and a patriarchal authority at all levels feature in the Afar mode of life. Descent is traced through the male line and women, while substantially contributing to household income earning, occupy only a marginal place in the society. The Afar people are known for their efficient communication skills and institutions. They are well versed and articulate in expressing their views in a disciplined manner, often consolidating their arguments using carefully selected idiomatic expressions and proverbs. Key words: Afar , culture, institutions, Ethiopia. INTRODUCTION The Afar people are Cushitic-speaking people living in the situated near permanent water sources and small trading arid and semi-arid areas of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti. centres (Yaynshet and Kelemework, 2004). Outsiders have used many different terms to refer to the Afar . These terms include Danakil, Adal and Teltal, even though the Afar liked none of them (Piquet, 2002). -

Trends and Spatio-Temporal Variation of Female

Tesema et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:719 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08882-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Trends and Spatio-temporal variation of female genital mutilation among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: a Spatio-temporal and multivariate decomposition analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health surveys Getayeneh Antehunegn Tesema1*, Chilot Desta Agegnehu2, Achamyeleh Birhanu Teshale1, Adugnaw Zeleke Alem1, Alemneh Mekuriaw Liyew1, Yigizie Yeshaw3 and Sewnet Adem Kebede1 Abstract Background: Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a serious health problem globally with various health, social and psychological consequences for women. In Ethiopia, the prevalence of female genital mutilation varied across different regions of the country. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the trend and determinants of female genital mutilation among reproductive-age women over time. Methods: A secondary data analysis was done using 2000, 2005, and 2016 Demographic Health Surveys (DHSs) of Ethiopia. A total weighted sample of 36,685 reproductive-age women was included for analysis from these three EDHS Surveys. Logit based multivariate decomposition analysis was employed for identifying factors contributing to the decrease in FGM over time. The Bernoulli model was fitted using spatial scan statistics version 9.6 to identify hotspot areas of FGM, and ArcGIS version 10.6 was applied to explore the spatial distribution FGM across the country. (Continued on next page) * Correspondence: [email protected] 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia Full list of author information is available at the end of the article © The Author(s). -

Somali Region: Multi – Agency Deyr/Karan 2012 Seasonal Assessment Report

SOMALI REGION: MULTI – AGENCY DEYR/KARAN 2012 SEASONAL ASSESSMENT REPORT REGION Somali Regional State November 24 – December 18, 2012 DATE ASSESSMENT STARTED & COMPLETED TEAM MEMBERS – Regional analysis and report NAME AGENCY Ahmed Abdirahman{Ali-eed} SCI Ahmed Mohamed FAO Adawe Warsame UNICEF Teyib Sheriff Nur FAO Mahado Kasim UNICEF Mohamed Mohamud WFP Name of the Agencies Participated Deyr 2012 Need Assessment Government Bureaus DRMFSS, DPPB,RWB,LCRDB,REB,RHB,PCDP UN – WFP,UNICEF,OCHA,FAO,WHO Organization INGO SCI,MC,ADRA,IRC,CHF,OXFAMGB,Intermon Oxfam, IR,SOS,MSFH,ACF LNGO HCS,OWDA,UNISOD,DAAD,ADHOC,SAAD,KRDA 1: BACKGROUND Somali Region is one of largest regions of Ethiopia. The region comprises of nine administrative zones which in terms of livelihoods are categorised into 17 livelihood zones. The climate is mostly arid/semi-arid in lowland areas and cooler/wetter in the higher areas. Annual rainfall ranges from 150 - ~600mm per year. The region can be divided into two broader rainfall regimes based on the seasons of the year: Siti and Fafan zones to the north, and the remaining seven zones to the south. The rainfall pattern for both is bimodal but the timings differ slightly. The southern seven zones (Nogob, Jarar, Korahe, Doollo, Shabelle, Afder, Liban and Harshin District of Fafan Zone) receive ‘Gu’ rains (main season) from mid April to end of June, and secondary rains known as ‘Deyr’ from early October to late December. In the north, Siti and Fafan zones excluding Harshin of Fafan zone receive ‘Dirra’ - Objectives of the assessment also known as ‘Gu’ rains from late March To evaluate the outcome of the Deyr/Karan to late May. -

Emergency Drought Response Project in Gode, Adadle, Kelafo and Mustahil Woredas of Gode Zone, Somali Region

Final Project Evaluation Emergency Drought Response Project in Gode, Adadle, Kelafo and Mustahil Woredas of Gode Zone, Somali Region Participatory Research and Evaluation Consultancy (PRE) August 2012 Content SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................IV 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT INTERVENTION AREA ......................................................... 1 1.2 BACKGROUND TO SC UK’ S EMERGENCY DROUGHT RESPONSE ........................................ 2 2. THE FINAL EVALUATION ........................................................................................ 4 2.1 SCOPE OF THE EVALUATION .................................................................................. 4 2.2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................. 4 2.2.1 Overall approach......................................................................................... 4 2.2.2 Desk review................................................................................................ 5 2.2.3 Field assessment......................................................................................... 5 2.2.4 Data collection and analysis ......................................................................... 9 3. EVALUATION FINDINGS ........................................................................................ -

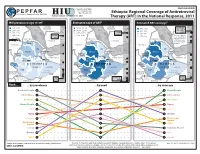

Ethiopia: Regional Coverage of Antiretroviral U.S

U.S. Department of State UNCLASSIFIED [email protected] PEPFAR http://hiu.state.gov Ethiopia: Regional Coverage of Antiretroviral U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief HUMANITARIAN INFORMATION UNIT Therapy (ART) in the National Response, 2011 HIV prevalence (age 15-49)1 Estimated need of ART2 Estimated ART coverage2 SAUDI Percent SAUDI In Percent 5.0% - 6.5% ARABIA 54,000 - 110,000 ARABIA thousands 80% or more Harari People, 2.0% - 4.9% Red 31,000 - 53,000 Red Red Addis Ababa* 110 50% - 79% >95% 1.5% - 1.9% Sea 7% 9,800 - 30,000 Sea Oromia Sea 100% 108,485 30% -49% 0.9% - 1.4% Gambela 1,900 - 9,700 29% or less *Coverage appears 6.5% to exceed estimated 0 100 200 km regional need due ERITREA 6 ERITREA ERITREA to ART provision to YEMEN YEMEN 90 0 100 200 mi clients from outside 80 Tigray Tigray Tigray the region. SUDAN SUDAN SUDAN 5 Afar Gulf of Afar Gulf of Afar Gulf of Aden Aden 70 Aden Amhara DJIBOUTI Amhara DJIBOUTI Amhara DJIBOUTI 60 Binshangul 4 Binshangul Binshangul Gumuz Dire Dawa Gumuz Dire Dawa Gumuz Dire Dawa SOMALIA SOMALIA SOMALIA Addis Harari Addis Harari 50 Addis Harari Ababa 3 Ababa Ababa People People People 40 Gambela ETHIOPIA Gambela ETHIOPIA Gambela ETHIOPIA People People People Oromia Somali Oromia Somali Oromia Somali 2 30 SNNP Provisional SNNP Provisional SNNP Provisional SOUTH administrative SOUTH administrative SOUTH administrative 20 SUDAN line SUDAN line SUDAN line 1 Somali Administrative SNNP Administrative Harari People 10 Administrative boundary 0.9% boundary 1,879 boundary 10% KENYA KENYA KENYA Rank ..