“My Pilgrimage to Nonviolence” the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sermons of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr

The Sermons of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. A Jewish Response Elliot B. Gevtel T hough it has been an official state and federal observance only for less than a decade, it seems that we have always blessed the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., through the almost two decades since he was tragically gunned down by a madman, at the prime of life, when his intellec tual and political gifts and talents were in full blossom and gave promise of even fuller growth in every way. It’s good and appropriate that we have a special day to mark his achievements. We need only hear his name to recall his uniQue and stunning powers of oratory which yielded the immortal “I Have A Dream” address, as important to our national heritage as Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg or FDR’s various inaugural addresses. King’s greatness is such that whenever we think of the turbulence of the Sixties, we mark his courage in the cause of nonviolent demonstration for civil rights, for in his peaceful but forceful use of boycotts and sit-ins and prayer he subjected himself to terrible dangers of brutality at the hands of sheriffs and deputies and mobs, not to mention malevolent men in seats of national power, who regarded his message of eQual rights and opportunities to be a greater threat to their petty prejudices than the worst criminal action. When we ask if there is such a thing as a modern prophet, we recall that many found in his unforgettable oratory and in his risking of life and limb for the message he bore—the spirit and the uncompromising truth of the Hebrew Prophets of old. -

Martin Luther King Jr Martin Luther King’S Book, the Time Magazine Honors Dr King As “Man Violent Riots Where Do We Go from 1946 1955 Measure of a Man Is Published

1959 1964 1966 1967 Martin Luther King Jr Martin Luther King’s book, The Time magazine honors Dr King as “Man Violent riots Where Do We Go From 1946 1955 Measure of a Man is published. of the Year”. Dr King’s third book, Why continue to Here, Dr King’s fourth book The US Supreme Court Rosa Parks is arrested We Can’t Wait is published. Dr King is break out. is published. Thurgood bans segregation in for refusing to give up 1958 1960 arrested for trying to eat in a “whites only” Dr King Marshall is the first interstate bus travel. her bus seat to a white Dr King is Dr King and his family restaurant. Lyndon B. Johnson signs the marches for African American on the Race riots begin. passenger. Dr King stabbed by a move to Atlanta. He is Public Accommodation and Fair Employment open housing US Supreme Court. Dr King 1986 President Truman 1929 becomes the president woman while arrested for breaking sections of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. in Chicago. makes an appeal for people Martin Luther King, Jr. Day 2004 investigates racism in Martin Luther King, of the Montgomery at a book Georgia’s trespassing laws Martin Luther King, Jr. is the youngest He is stoned to stop rioting, as may becomes a national holiday Dr King is awarded a America. Jr. is born. Improvement Association. signing. while picketing in Atlanta. person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. by onlookers. participants are being killed. in the US. Congressional Gold Medal. 1900 2000 Overlap pages here pages Overlap 1947 1953 1956 1961 1965 1968 1968 Dr King decides King marries Dr King’s house is bombed. -

The Political Thought of Martin Luther King, Jr

POSC 351 The Political Thought of Martin Luther King, Jr. Winter 2013 Prof: Barbara Allen Tues Thurs WCC239 WCC 231 Mon – Thurs by appointment 10:10- 11:55 Sign up Using Moodle The Course This interdisciplinary seminar will examine the speeches, sermons, and writings of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. We will study King’s ideas as part of the larger discourse of non-violence and social justice that is foundational to King’s political action. King’s articulation of these ideas can be understood in several contexts: as part of a tradition of African-American political thought, as embedded in African-American Christian tradition, as a contribution to American civil religion, as an example of self-governing, vigilant citizenship expressed by The Federalist, and as part of an American tradition of optimism and eclectic liberal philosophy and action. We will look at King’s ideas in the context of the civil rights movement using historical assessments of the movement and its goals and through the lens of contemporary models of collective action, especially the dilemmas of coordinated, voluntary political participation. One of our goals will be to draw out the complexities of these ideas to see how they challenge the practice of democracy in the US and liberal political theory today. We will also look more broadly at the pan-African anti-colonial struggle with writings from three contemporaries of King, Frantz Fanon, Albert Memmi, and Amilcar Cabral. The reciprocal influences of these writers help us add another dimension to our study of liberation, civil rights, and social justice as a global challenge. -

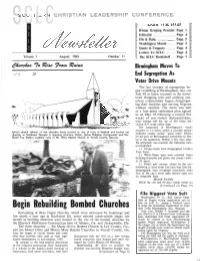

Letters to SCLC

OUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE N INSIDE THIS ISSUE ~ii' B'ham Keeping Promise Page ::1::: Editorial ___ ___ __ ______ ___ ___ ____ Page i :i.:",,'I.:':I.: I Volume 1 August, 1963 Number 11 ~~~~~~~bThe SCLC Bookshelf~~ ~__ __ gPage :7 :1:ii: Birmingham Moves To End Segregation As Voter Drive Mounts The last vestiges of segregation be gan crumbling in Birmingham, Ala., on .•' July 30 as lunch counters in the down town shopping area and outlying sub urban communities began desegregat ing their facilities and serving Negroes without incident. The move was part ~. of a four-point settlement plan agreed to on May 10 following a crucial five _ ....".. ... , .. ,. '¥l weeks of non-violent demonstrations, mass jailings and the use of fire hoses and vicious K-9 corps police dogs. The integration of Birmingham's lunch counters in 14 stores within a two-day period Artist's sketch (above) of new churches being erected on site of ruins of bombed and burned out churches in Southwest Georgia is imposing structure. Below, Jackie Robinson (foreground) and Rev. followed closely earlier "good faith" efforts Wyatt Tee Walker examine ruins of Mt. Olive Baptist Church in Terrell County, Georgia. on the part of Birmingham authorities to live up to the agreement. Within a few days after the settlement was reached, the following were accomplished: I.) Fitting rooms were desegregated (within three days). 2.) White-Negro signs were removed from drinking fountains and public rest rooms (with in 30 days) . 3.) Public golf courses, closed by the city following a court order last year that they be desegregated, were re-opened voluntarily with four of the city's seven links thrown open on an integrated basis. -

The Life of Martin Luther King, Jr

Table of Contents The Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection, located in the Business & Government Division of the Main Library, was dedicated January 20, 1985. It includes material by and about Dr. King, other civil rights activists, and the Civil Rights movement in the United States. New materials are added to the Library’s collection on a regular basis. Consult a Business & Government librarian for help finding the most current title. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. THE LIFE OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. …………… 1 SPEECHES, WRITINGS, AND PHILOSOPHY ..…….. 4 ASSASSINATION …………………………………………………. 6 AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY ……………………… 7 CIVIL RIGHTS THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES ……………………… 9 DESEGREGATION ………………………………… 13 DISCRIMINATION AND RACISM …………. 14 RELIGION AND CIVIL RIGHTS ……………. 16 PROTEST ……………………………………………… 17 NONVIOLENCE ……………………………………. 19 MALCOLM X …………………………………………. 20 OTHER NOTABLE AFRICAN-AMERICANS .............. 21 DVDS …………………………………………………………………………… 23 WEBSITES ………………………………………........................ 25 MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. COLLECTION PERIODICAL REFERENCE ………………………………......... 26 AKRON-SUMMIT COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCATIONS …………………………………........................... 27 The Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. Baldwin, Lewis V. Collins, David R. THERE IS A BALM IN GILEAD NOT ONLY DREAMERS MLK 323.092 K53B, 1991 MLK 323.4092 K53C, 1986 Bennett, Lerone, Jr. Clark, Kenneth B. WHAT MANNER OF MAN KING, MALCOLM, BALDWIN: MLKBIO KING, M B471W, 1992 THREE INTERVIEWS MLK 323.4097 K53K, 1985 Bishop, James Alonzo Darby, -

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day of Service SERVICE-LEARNING CURRICULUM a Guidebook for Schools, Organizations & Parents

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day of Service SERVICE-LEARNING CURRICULUM A Guidebook for Schools, Organizations & Parents Created and Authored by: Davida Hopkins-Parham, Executive Assistant to the Vice President for Academic Affairs, CSUF Jeannie Kim-Han, Acting Director, CSUF Center for Internships & Service-Learning Marcina Riley, Student Assistant, CSUF Center for Internships & Service-Learning Melissa Runcie, Senior Program Coordinator, Orange County AmeriCorps Alliance Julie Stokes, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Director of the CSUF African American Resource Center California State University, Fullerton SERVICE-LEARNING CURRICULUM TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Why We Serve 1 Curriculum Guide Overview 1 Suggestions for Making the Curriculum Work For You 2 Quotes of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. 3 Values and Vocabulary Words 4 Timeline of the Life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. 5 Section I: Historical Sketches Biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. 10 Upbringing 14 Ideas and Philosophy 16 Youth Edition: Biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. 17 Youth Edition: Childhood and Upbringing 20 Youth Edition: Ideas of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. 22 Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. 23 Actions of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. 31 Section II: MLK Learning Toolkit Coloring Worksheets 34 Drawing Activities 37 Writing Activities 39 Comprehension Activities 43 Puzzles and Mazes 78 Discussion Questions 60 Section III: MLK Reflection Toolkit A Few Words About Reflection 61 Facilitating Reflection Activities 61 Reflecting on Service 62 Reflecting on MLK Values 63 Section IV: Resources Bibliography 64 Children’s Books 64 Websites 64 California Martin Luther King, Jr. Day of Service Grants Program SERVICE-LEARNING CURRICULUM INTRODUCTION Why We Serve On Monday, January 20, 1986, the first national celebration took place in honor of Dr. -

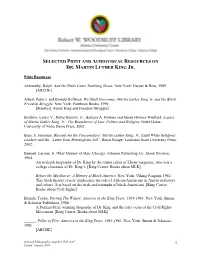

View Selected Bibliography of Resources on Dr. Martin Luther King

SELECTED PRINT AND AUDIOVISUAL RESOURCES ON DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. Print Resources Abernathy, Ralph. And the Walls Came Tumbling Down. New York: Harper & Row, 1989. [ARCHE] Albert, Peter J. and Ronald Hoffman. We Shall Overcome: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: Pantheon Books, 1990. [Stanford: About King and Freedom Struggle] Baldwin, Lewis V., Rufus Burrow, Jr., Barbara A. Holmes and Susan Holmes Winfield. Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.: The Boundaries of Law, Politics and Religion. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2002. Bass, S. Jonathan. Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King, Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders and the “Letter from Birmingham Jail”. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002. Bennett, Lerone, Jr. What Manner of Man. Chicago: Johnson Publishing Co., Book Division, 1964. An in-depth biography of Dr. King by the senior editor of Ebony magazine, who was a college classmate of Dr. King’s. [King Center: Books about MLK] _____. Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America. New York: Viking Penguin, 1984. This black history classic emphasizes the role of African-Americans in American history and culture. It is based on the trials and triumphs of black Americans. [King Center: Books about Civil Rights] Branch, Taylor. Parting The Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-1963. New York: Simon & Schuster Publishers, 1988. A Pulitzer-Prize winning biography of Dr. King and the early years of the Civil Rights Movement. [King Center: Books about MLK] ______. Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-1965. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981. -

BLACK STUDENTS UNION Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ML King Rally

BLACK STUDENTS UNION Dr. MartinLuther King Jr. ML King Rally January 14, Noon RevellePlaza k StevieWonder, 200,000 Rally to SupportNational King Holiday 200.000braved freezing Washington D.C. temperatureslast Januaryto march in supportof legislationto make Dr. Martinl.uther King’s birthday a nationalholiday. The campaignwas spearheadedby entertainerStevie Wonder. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO VOL. 6, NO. 2 JANUARY, 1983 Universityof California,San Diego Vol.6, No. 2 January 1 HAVE A DREAM MLK:With the violencein Selma, whenthey spoke in broadterms of societyis essentiallyhospitable tolair By JulesBagneris Alabama,(where the sheriff had freedomand justice. But the absence playand to steadygrowth toward a directedhis fiaen in tear-gassing and When asked about Martin Luther of brutalityand unregenerate evil is middle-classUtopia embodying racial beatingthe marchers to theground; notthe presence of justice.To staya harmony.But unfortunately this is a KingJr., most people respond that he thenation saw andheard this and murderis notthe same thing as to fantasyof self-deceptionand wasa greatman with a visionfor the thereforeexploded in indignation)and ordainbrotherhood. The wordwas comfortablevanity. Overwhelmingly, future.Some respond that he was theVoting Rights Act one phaseof broken,and the freerunning Americais stillstruggling with concernedabout racial equality and developmentin the civil rights expectationsof Blacks crushed into irresolutionandcontradictions. It has equalopportunity for all Americans. revolutioncame to an end.A new thestone walls of whiteresistance. The beensincere and even ardent in Stillothers respond that he wasa phaseopened, but few observers resultwas havoc. Blacks felt cheated. welcomingsome change. But too !Communistconspirator intent upon realizedit or wereprepared for its especiallyin theNorth. while many quicklyapathy and disinterest rise to i overthrowingthecapitalist system. -

Rebel Spirits: Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr

REBEL SPIRITS: ROBERT F. KENNEDY AND MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. Books | Articles | DVDs | Collections | Oral Histories | YouTube | Websites | Podcasts Visit our Library Catalog for a complete list of books, magazines and videos. Resource guides collate materials about subject areas from both the Museum’s library and permanent collections to aid students and researchers in resource discovery. The guides are created and maintained by the Museum’s librarian/archivist and are carefully selected to help users, unfamiliar with the collections, begin finding information about topics such as Dealey Plaza Eyewitnesses, Conspiracy Theories, the 1960 Presidential Election, Lee Harvey Oswald and Cuba to name a few. The guides are not comprehensive and researchers are encouraged to email [email protected] for additional research assistance. The following guide focuses on the Museum’s 2018 temporary exhibition Rebel Spirits: Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. presented in commemoration of the fiftieth anniversaries of the assassination of both these iconic individuals. The resources below are related to the events, persons and time period depicted in exhibit photographs and text, shedding light on the converging paths of Kennedy and King, two American leaders who came from such different worlds. Rebel Spirits: Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. was produced by Wiener Schiller Productions and is presented locally by The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. The exhibition was curated by Lawrence Schiller with support from Getty Images. BOOKS The selections below compare and contrast the lives and legacies of Kennedy and King. The authors reflect upon the complexity of their character, the significance of their enigmatic relationship and how their deaths impacted the nation. -

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2020 Resources

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2020 Resources www.discipleshomemissions.org January, 2020 Historical Facts Dear Beloved Community, 1929 Born Martin Luther King, Jr. on January 15 in Atlanta, Ga. “NO WORK IS INSIGNIFICANT. ALL LABOR THAT UPLIFTS 1948 Graduates from Morehouse College, ordained HUMANITY HAS DIGNITY AND IMPORTANCE AND SHOULD a Baptist minister BE UNDERTAKEN WITH PAINSTAKING EXCELLENCE.” Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. 1951 Graduates from Crozier Theological Seminary I have always honored and commemorated life of the Rev. 1953 Marries Coretta Scott Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on his birthday.. My mother 1954 Becomes pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist would take us to a play, concert, museum, parade or Church, Montgomery, Ala. gathering where we would learn and honor the life of Dr. 1955 Receives PH.D. degree in Systematic Theology King. That evening, I would write up a full report on what from Boston University; Rosa Parks, arrested I experienced and learned that day. for refusing to give up her seat on segregated The next day I would return to school with my report and bus sparks the Montgomery bus boycott; a note from my mother, which read, “ Dear Teacher, Sheila becomes president of the Montgomery was out to commemorate and celebrate the legacy of Dr. Improvement Association; first child, Yolanda Martin Luther King, Jr. She has completed a summary of is born the day and what she experienced…..” 1957 King founds the Southern Christian My mother predicted my teacher’s response because the Leadership Conference (SCLC); organizes the letter closed with, “I realize that this is not recognized as Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom; awarded the an official holiday, but it should be. -

Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday

Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday, January 21, 2008 Celebrate the Book with Penrose Library! Selected videorecordings are listed at the bottom of this document Abernathy, Donzaleigh Partners to history: Martin E185.61 .A165 2003 Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and the Civil Rights Movement Anderson, Ho Che KING: A Comics Biography of E185.61 .A547 2005 Martin Luther King, Jr. Ansbro, John J. Martin Luther King, Jr.: The E185.97.K5 A 79 1982 Making of a Mind Baldwin, Lewis V. There is a Balm in Gilead: The E185.97.K5 B35 1991 Cultural roots of Martin Luther King, Jr. To Make the Wounded Whole: E185.97.K5 B353 1992 The Cultural Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. The Legacy Of Martin Luther E185.97.K5 L35 2002 King, Jr.: The Boundaries of Law, Politics, and Religion Blessed are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King Jr., Eight White Religious leaders, and the “Letter from Birmingham Bass, S. Jonathan Jail” F334.B69 N415 2001 At the River I Stand: Memphis, The 1968 Strike, and Martin HD5325.S2572 1968 .M46 Beifuss, Joan Turner Luther King 1989 Bobbitt, David A. The Rhetoric of Redemption E185.97.K5 B58 2004 Parting the Waters: America in E185.61 .B7914 1988 the King Years 1954-63 Pillar of Fire: America in the Branch, Taylor King Years 1963-65 E185.61 .B7915 1998 Burns, Stewart To The Mountain Top E185.97.K5 B798 2004 Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Sermonic Power of Public Calloway-Thomas, Carolyn Discourse E185.97.K5 M32 1993 Carson, Clayborne A Call To Conscience E185.97.K5 A5 2002 Chassman, Gary In the Spirit of Martin: The Living Legacy of Dr. -

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

JAIL, IN THANKS TO YOU FOR YOUR DEEP COMMITMENT TO THE CONCEPT OF 26 Oct NO VIOLENCE, AND YOUR VISION OF A FREE SOCIETY WHICH MAKES POSSIBLE 1960 THIS STUDENT MOVEMENT. YOU SAT IN WITH US, YOU WENT TO JAIL WITH US, WE WANT YOU TO KNOW THAT THE FIGHT WILL NOT END FOR WE HAVE TAKEN UP THE TORCH FOR FREEDOM, WE WILL NOT FORGET THAT YOU ARE BEHIND IRON BARS. WE ASK THAT YOU REMEMBER US AS WE TRY TO REMOVE THE BARS THAT EXIST IN THE HEARTS OF MEN. YOURS IN THE CAUSE FOR FREEDOM THE STUDENT NON VIOLENT COORDINATING COMMITTEE MARION S BARRY JR-CHAIRMAN-EDWARD BIKING JR-ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARY. PHWSr. MLKJP-CAMK:Vault Box 5. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project To Coretta Scott King [ 2 6 October 19601 Reidsville, Ga. King m’tes to his wqefefrom the Georgia State Prison at Reidrville. He tells her “that it is extremely dificult for me to think of being awayfrom you and my Yoki and Marty for four months” but that his ordeal “is the cross that we must bearfor thefreedom of our people.” Hello Darling, Today I find myself a long way from you and the children. I am at the State Prison in Reidsville which is about 230 miles from Atlanta. They picked me up from the DeKalb jail about 4 ’0 clock this morning.’ I know this whole experience is very difficult for you to adjust to, especially in your condition of pregnancy, but as I said to you yesterday this is the cross that we must bear for the freedom of our people.2 So I urge you to be strong in in faith, and this will in turn strengthen me.