Starting Off with a Bang: the Whirl of Reflexive and Metatextual Images in the Pilot Episodes to Three ABC Series ( Desperate Housewives , Lost and Flashforward )”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story: http://www.usatoday.com/life/people/2005-11-21-huffman_x.htm Felicity Huffman is sitting pretty: Emmy-winning Housewives star ignites Oscar talk for transsexual role By William Keck, USA TODAY By Dan MacMedan, USA TODAY Has it all: An actress for more than twenty years, Felicity Huffman has an Emmy for her role on hit Desperate Housewives, a critically lauded role in the film Transamerica, a famous husband (William H. Macy) and two daughters. 2 WEST HOLLYWOOD Felicity Huffman is on a wild ride. Her ABC show, Desperate Housewives, became hot, hot, hot last season and hasn't lost much steam. She won the Emmy in September over two of her Housewives co-stars. And now she is getting not just critical praise, but also Oscar talk, for her performance in the upcoming film Transamerica, in which she plays Sabrina "Bree" Osbourne, a pre- operative man-to-woman transsexual. After more than 20 years as an actress, this happily married, 42-year-old mother of two is today's "it" girl. "It couldn't happen to a nicer gal," says Housewives creator Marc Cherry. "Felicity is one of those success stories that was waiting to happen." Huffman has enjoyed the kindness of critics before, particularly for her role on Sports Night, an ABC sitcom in the late '90s. And Cherry points out that her stock in Hollywood has been high. "She has always had the respect of this entire industry," he says. But that's nothing like having a hit show and a movie with awards potential, albeit a modestly budgeted, art house-style film. -

California Court Finds Wrongful Termination Tort Too Desperate, but Permits Statutory Claim for Disparate Treatment

Management Alert California Court Finds Wrongful Termination Tort Too Desperate, But Permits Statutory Claim For Disparate Treatment California employees can file tort claims against employers who impose adverse employment actions in violation of public policy. They have used this theory to challenge wrongful terminations and demotions. In Touchstone Television Productions v. Superior Court (Sheridan), the California Court of Appeal rejected an effort to extend this tort theory to an employer’s decision not to exercise an option to renew a contract. The Facts In 2004, Touchstone Television Productions (“Touchstone”) hired actress Nicollette Sheridan (“Sheridan”) to appear in a new television series, Desperate Housewives. The parties’ agreement gave Touchstone the option to annually renew Sheridan’s employment for up to six additional seasons. Touchstone exercised its option to renew the agreement with Sheridan for Seasons 2, 3, 4, and 5. During Season 5, Sheridan reported to Touchstone that Marc Cherry, the series’ creator, had hit her during the filming of an episode. Five months after this alleged incident, Touchstone informed Sheridan that it would not exercise its option to renew her contract for Season 6, because her character would be killed during Season 5. Sheridan continued to work during Season 5, filming three more episodes and doing publicity for the series. Sheridan sued Touchstone and Cherry in April 2010. She asserted various claims, including a claim that Touchstone fired her in retaliation for complaining about Cherry’s conduct. The Trial Court Decision The matter went to trial in February 2012. The jury deadlocked on the wrongful termination claim and the trial court declared a mistrial. -

Academic Catalog 2021-2022 ACADEMIC STANDARDS

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 5 PURPOSE .......................................................................................................................................... 5 MISSION ............................................................................................................................................. 5 VALUES .............................................................................................................................................. 5 INSTITUTIONAL VISION .................................................................................................................... 5 INSTITUTIONAL OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................... 5 ACCREDITATION AND OPERATIONAL STATUS............................................................................. 5 COLLEGE COMMUNITY ................................................................................................................... 6 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................................................................................................. 6 OUR FACULTY ................................................................................................................................................ 6 OUR ALUMNI ......................................................................................................................... -

LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04

LOST “Raised by Another” CAST LIST BOONE................................Ian Somerhalder CHARLIE..............................Dominic Monaghan CLAIRE...............................Emilie de Ravin HURLEY...............................Jorge Garcia JACK.................................Matthew Fox JIN..................................Daniel Dae Kim KATE.................................Evangeline Lilly LOCKE................................Terry O’Quinn MICHAEL..............................Harold Perrineau SAWYER...............................Josh Holloway SAYID................................Naveen Andrews SHANNON..............................Maggie Grace SUN..................................Yunjin Kim WALT.................................Malcolm David Kelley THOMAS............................... RACHEL............................... MALKIN............................... ETHAN................................ SLAVITT.............................. ARLENE............................... SCOTT................................ * STEVE................................ * www.pressexecute.com LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04 LOST “Raised by Another” SET LIST INTERIORS THE VALLEY - Late Afternoon/Sunset CLAIRE’S CUBBY - Night/Dusk/Day ENTRANCE * ROCK WALL - Dusk/Night/Day * INFIRMARY CAVE - Morning JACK’S CAVE - Night * LOFT - Day - FLASHBACK MALKIN’S HOUSE - Day - FLASHBACK BEDROOM - Night - FLASHBACK LAW OFFICES CONFERENCE ROOM - Day - FLASHBACK EXTERIORS JUNGLE - Night/Day ELSEWHERE - Day CLEARING - Day BEACH - Day OPEN JUNGLE - Morning * SAWYER’S -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

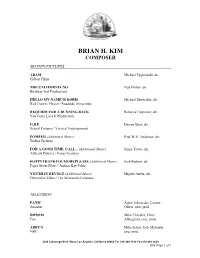

Brian H. Kim Composer

BRIAN H. KIM COMPOSER MOTION PICTURES ADAM Michael Uppendahl, dir. Gilbert Films THE CALIFORNIA NO Ned Ehrbar, dir. Birthday Suit Productions HELLO MY NAME IS DORIS Michael Showalter, dir. Red Crown / Haven / Roadside Attractions REQUIEM FOR A RUNNING BACK Rebecca Carpenter, dir. You Gotta Love It Productions G.B.F. Darren Stein, dir. School Pictures / Vertical Entertainment POMPEII (Additional Music) Paul W.S. Anderson, dir. TriStar Pictures FOR A GOOD TIME, CALL... (Additional Music) Jamie Travis, dir. AdScott Pictures / Focus Features HAPPYTHANKYOUMOREPLEASE (Additional Music) Josh Radnor, dir. Paper Street Films / Anchor Bay Films YOUTH IN REVOLT (Additional Music) Miguel Arteta, dir. Dimension Films / The Weinstein Company TELEVISION PANIC Adam Schroeder, Lauren Amazon Oliver, exec prod. BH90210 Mike Chessler, Chris Fox Alberghini, exec prod. ABBY’S Mike Schur, Josh Malmuth, NBC exec prod. 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Kim Page 1 of 3 BRIAN H. KIM COMPOSER TELEVISION (continued) GHOSTING: THE SPIRIT OF CHRISTMAS Lisa Kudrow, Dan Bucatinsky, Freeform exec prod. SEARCH PARTY Michael Showalter, exec prod. TBS STAR VS. THE FORCES OF EVIL Daron Nefcy, exec prod. Disney Television Animation / Disney XD SIGNIFICANT MOTHER Tripp Reed, Leslie Morgenstein, CW exec prod. DATING RULES FROM MY FUTURE SELF Bob Levy, Tripp Reed, exec Hulu prod. FRIENDS-IN-LAW (pilot) Brian Gallivan, exec prod. NBC / Warner Brothers MOST LIKELY TO (pilot) Greg Berlanti, Diablo Cody, Berlanti Productions / ABC exec prod. ADULT CONTENT (pilot) Topher Grace, Jenna Fischer, 20th Century Fox prod. GOOD FORTUNE (pilot) Kourtney Kang, Matt Zinman, NBC exec prod. -

Flying the Line Flying the Line the First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association

Flying the Line Flying the Line The First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association By George E. Hopkins The Air Line Pilots Association Washington, DC International Standard Book Number: 0-9609708-1-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 82-073051 © 1982 by The Air Line Pilots Association, Int’l., Washington, DC 20036 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Printing 1982 Second Printing 1986 Third Printing 1991 Fourth Printing 1996 Fifth Printing 2000 Sixth Printing 2007 Seventh Printing 2010 CONTENTS Chapter 1: What’s a Pilot Worth? ............................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Stepping on Toes ...................................................................... 9 Chapter 3: Pilot Pushing .......................................................................... 17 Chapter 4: The Airmail Pilots’ Strike of 1919 ........................................... 23 Chapter 5: The Livermore Affair .............................................................. 30 Chapter 6: The Trouble with E. L. Cord .................................................. 42 Chapter 7: The Perils of Washington ........................................................ 53 Chapter 8: Flying for a Rogue Airline ....................................................... 67 Chapter 9: The Rise and Fall of the TWA Pilots Association .................... 78 Chapter 10: Dave Behncke—An American Success Story ......................... 92 Chapter 11: Wartime............................................................................. -

LOST the Official Show Auction

LOST | The Auction 156 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 572. JACK’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO 574. JACK’S COSTUME FROM PLACE LIKE HOME, PARTS 2 THE EPISODE, “EGGTOWN.” & 3.” Jack’s distressed beige Jack’s black leather jack- linen shirt and brown pants et, gray check-pattern worn in the episode, “There’s long-sleeve shirt and blue No Place Like Home, Parts 2 jeans worn in the episode, & 3.” Seen on the raft when “Eggtown.” $200 – $300 the Oceanic Six are rescued. $200 – $300 573. JACK’S SUIT FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE 575. JACK’S SEASON FOUR LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Jack’s COSTUME. Jack’s gray pants, black suit (jacket and pants), striped blue button down shirt white dress shirt and black and gray sport jacket worn in tie from the episode, “There’s Season Four. $200 – $300 No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 157 www.liveauctioneers.com LOST | The Auction 578. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Kate’s jeans and green but- ton down shirt worn at the press conference in the episode, “There’s No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 576. JACK’S SEASON FOUR DOCTOR’S COSTUME. Jack’s white lab coat embroidered “J. Shephard M.D.,” Yves St. Laurent suit (jacket and pants), white striped shirt, gray tie, black shoes and belt. Includes medical stetho- scope and pair of knee reflex hammers used by Jack Shephard throughout the series. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

California Court of Appeal Opinion

Filed 10/20/15 CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA SECOND APPELLATE DISTRICT DIVISION FOUR NICOLLETTE SHERIDAN, B254489 Plaintiff and Appellant, (Los Angeles County Super. Ct. No. BC435248) v. TOUCHSTONE TELEVISION PRODUCTIONS, LLC, Defendant and Respondent. APPEAL from a judgment of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County, Michael L. Stern, Judge. Reversed. Baute Crochetiere & Gilford, Mark D. Baute and David P. Crochetiere; Greines, Martin, Stein & Richland and Robin Meadow for Plaintiff and Appellant. Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp, Adam Levin, Aaron M. Wais and Jorja A. Cirigliana; Horvitz & Levy, Mitchell C. Tilner and Frederic D. Cohen for Defendant and Respondent. Touchstone Television Productions (Touchstone) hired actress Nicollette Sheridan to appear in the television series Desperate Housewives, a show created by Marc Cherry.1 Sheridan sued Touchstone under Labor Code section 6310,2 alleging that Touchstone fired her in retaliation for her complaint about a battery allegedly committed on her by Cherry. The trial court sustained Touchstone’s demurrer to the complaint on the basis that Sheridan failed to exhaust her administrative remedies by filing a claim with the Labor Commissioner. The sole issue on appeal is whether Sheridan was required to exhaust her administrative remedies under sections 98.7 and 6312. We conclude that she was not required to do so and therefore reverse. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND3 Touchstone hired Sheridan in 2004 under an agreement with her loan-out company Starlike Enterprises, to play the character of Edie Britt in the television series Desperate Housewives. The agreement was for the show’s initial season and 1 In a prior proceeding involving Touchstone and Sheridan, we granted Touchstone’s petition for writ of mandate and directed the superior court to grant Touchstone’s motion for a directed verdict on Sheridan’s cause of action for wrongful termination in violation of public policy. -

Desperate Housewives

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Musicologia e Scienze dello Spettacolo Tesi di Laurea Ai confini della serialità televisiva. Il caso Desperate Housewives Relatore Prof.ssa Valentina Carla Re Correlatori Prof.ssa Francesca Bisutti Prof. Fabrizio Borin Laureando Marta Bernardi Matricola 831546 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 2 Santa Marta protettrice delle casalinghe … Anche quelle disperate Ringraziamenti. Si ringrazia mamma e papà per il supporto e l’incoraggiamento a non mollare mai. Irene e Nadia, le mie sorelle perché la vita famigliare senza di loro sarebbe stata a dir poco noiosa. Insieme abbiamo passato dei bellissimi momenti che porterò sempre nel mio cuore. Un grazie anche a Giovanni e alla sua personalità perché riescono sempre a farmi sorridere anche nei momenti di maggior difficoltà. Infine un grazie alla Facoltà di Ingegneria di Trento perché ho capito quello che non avrei mai voluto diventare. 3 4 SOMMARIO INTRODUZIONE p. 7 I. UN QUADRO GENERALE: SULL’INIZIO E SULLA FINE NELLA SERIE SERIALIZZATA p. 13 I.1. SULLA NATURA DELLA SERIE SERIALIZZATA p. 15 I.2. LA COMPLESSITÁ NARRATIVA: CLIFFHANGER, INIZIO EPISODIO, EPISODIO PILOTA, LA CHIUSURA. p. 26 II. DESPERATE HOUSEWIVES. LA SERIE. II.1. L’EPITESTO PUBBLICO: LA GUIDA UFFICIALE DI DESPERATE HOUSEWIVES p. 58 II.2. LA SIGLA p. 71 II.3. L’EPISODIO PILOTA p. 102 II.4.TRA ANTHOLOGY PLOT E RUNNING PLOT, L’IMPORTANZA DEL RACCONTO E DELLE SUE REGOLE p. 135 II.5. IL GRAN FINALE p. 186 APPENDICE p. 321 BIBLIOGRAFIA p. 237 5 6 INTRODUZIONE Negli ultimi anni il panorama televisivo si è profondamente trasformato. I cambiamenti sopraggiunti hanno portato ad una nuova forma di serialità televisiva, di cui Desperate Housewives rappresenta un caso esemplare. -

Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series Par Toni Pape

Université de Montréal Figures of Time: Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series par Toni Pape Département de littérature comparée, Faculté des arts et des sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des arts et des sciences en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph. D. en Littérature, option Études littéraires et intermédiales Juillet 2013 © Toni Pape, 2013 Résumé Cette thèse de doctorat propose une analyse des temporalités narratives dans les séries télévisées récentes Life on Mars (BBC, 2006-2007), Flashforward (ABC, 2009-2010) et Damages (FX/Audience Network, 2007-2012). L’argument général part de la supposition que les nouvelles technologies télévisuelles ont rendu possible de nouveaux standards esthétiques ainsi que des expériences temporelles originales. Il sera montré par la suite que ces nouvelles qualités esthétiques et expérientielles de la fiction télévisuelle relèvent d’une nouvelle pertinence politique et éthique du temps. Cet argument sera déployé en quatre étapes. La thèse se penche d’abord sur ce que j’appelle les technics de la télévision, c’est-à- dire le complexe de technologies et de techniques, afin d’élaborer comment cet ensemble a pu activer de nouveaux modes d’expérimenter la télévision. Suivant la philosophie de Gilles Deleuze et de Félix Guattari ainsi que les théories des médias de Matthew Fuller, Thomas Lamarre et Jussi Parikka, ce complexe sera conçu comme une machine abstraite que j’appelle la machine sérielle. Ensuite, l’argument puise dans des théories de la perception et des approches non figuratives de l’art afin de mieux cerner les nouvelles qualités d’expérience esthétique dans la fiction sérielle télévisée.