Reflections on the Principalship in Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Music Collection

Christopher Lee :: Personal Music Collection electricshockmusic.com :: Saturday, 25 September 2021 < Back Forward > Christopher Lee's Personal Music Collection | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | | DVD Audio | DVD Video | COMPACT DISCS Artist Title Year Label Notes # Digitally 10CC 10cc 1973, 2007 ZT's/Cherry Red Remastered UK import 4-CD Boxed Set 10CC Before During After: The Story Of 10cc 2017 UMC Netherlands import 10CC I'm Not In Love: The Essential 10cc 2016 Spectrum UK import Digitally 10CC The Original Soundtrack 1975, 1997 Mercury Remastered UK import Digitally Remastered 10CC The Very Best Of 10cc 1997 Mercury Australian import 80's Symphonic 2018 Rhino THE 1975 A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships 2018 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful THE 1975 2016 Dirty Hit/Interscope Yet So Unaware Of It THE 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form 2020 Dirty Hit/Interscope THE 1975 The 1975 2013 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import {Return to Top} A A-HA 25 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino UK import A-HA Analogue 2005 Polydor Thailand import Deluxe Fanbox Edition A-HA Cast In Steel 2015 We Love Music/Polydor Boxed Set German import A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990 Warner Bros. German import Digitally Remastered A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD/1-DVD Edition UK import 2-CD/1-DVD Ending On A High Note: The Final Concert Live At A-HA 2011 Universal Music Deluxe Edition Oslo Spektrum German import A-HA Foot Of The Mountain 2009 Universal Music German import A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985 Reprise Digitally Remastered A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985, 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import Digitally Remastered Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Deluxe A-HA 1985, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 4-CD/1-DVD Edition Boxed Set German import A-HA Lifelines 2002 WEA German import Digitally Remastered A-HA Lifelines 2002, 2019 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import A-HA Memorial Beach 1993 Warner Bros. -

Recordings by Women Table of Contents

'• ••':.•.• %*__*& -• '*r-f ":# fc** Si* o. •_ V -;r>"".y:'>^. f/i Anniversary Editi Recordings By Women table of contents Ordering Information 2 Reggae * Calypso 44 Order Blank 3 Rock 45 About Ladyslipper 4 Punk * NewWave 47 Musical Month Club 5 Soul * R&B * Rap * Dance 49 Donor Discount Club 5 Gospel 50 Gift Order Blank 6 Country 50 Gift Certificates 6 Folk * Traditional 52 Free Gifts 7 Blues 58 Be A Slipper Supporter 7 Jazz ; 60 Ladyslipper Especially Recommends 8 Classical 62 Women's Spirituality * New Age 9 Spoken 64 Recovery 22 Children's 65 Women's Music * Feminist Music 23 "Mehn's Music". 70 Comedy 35 Videos 71 Holiday 35 Kids'Videos 75 International: African 37 Songbooks, Books, Posters 76 Arabic * Middle Eastern 38 Calendars, Cards, T-shirts, Grab-bag 77 Asian 39 Jewelry 78 European 40 Ladyslipper Mailing List 79 Latin American 40 Ladyslipper's Top 40 79 Native American 42 Resources 80 Jewish 43 Readers' Comments 86 Artist Index 86 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124-R, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 M-F 9-6 INQUIRIES: 919-683-1570 M-F 9-6 ordering information FAX: 919-682-5601 Anytime! PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are tem CATALOG EXPIRATION AND PRICES: We will honor don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and porarily out of stock on a title, we will automatically prices in this catalog (except in cases of dramatic schools). Make check or money order payable to back-order it unless you include alternatives (should increase) until September. -

© Copyright 2020 Young Dae

© Copyright 2020 Young Dae Kim The Pursuit of Modernity: The Evolution of Korean Popular Music in the Age of Globalization Young Dae Kim A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: Shannon Dudley, Chair Clark Sorensen Christina Sunardi Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music University of Washington Abstract The Pursuit of Modernity: The Evolution of Korean Popular Music in the Age of Globalization Young Dae Kim Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Shannon Dudley School of Music This dissertation examines the various meanings of modernity in the history of Korean pop music, focusing on several crucial turning points in the development of K-pop. Since the late 1980s, Korean pop music has aspired to be a more advanced industry and establish an international presence, based on the economic leap and democratization as a springboard. Contemporary K-pop, originating from the underground dance scene in the 1980s, succeeded in transforming Korean pop music into a modern and youth-oriented genre with a new style dubbed "rap/dance music." The rise of dance music changed the landscape of Korean popular music and became the cornerstone of the K-pop idol music. In the era of globalization, K-pop’s unique aesthetics and strategy, later termed “Cultural Technology,” achieved substantial returns in the international market. Throughout this evolution, Korean Americans were vital players who brought K-pop closer to its mission of modern and international pop music. In the age of globalization, K-pop's modernity and identity are evolving in a new way. -

640.2018.Pdf

January 1, 2018 We Stood Like Kings - Machines (Live Session) https://youtu.be/rczgOGdDCA8 Filmed in September 2017 in Habay-la- Neuve, Belgium. Published on 6 Jan 2018 Empire / Hexagon by We Deserve This (Germany) https://wedeservethis.bandcamp.com/album/empire-hexagon released January 7, 2018 Rise by Echoes Across The Sky (Long Island, NY) https://echoesacrossthesky.bandcamp.com/ released January 1, 2018 Floating Just Below the Ice by INANITION (Earthwalker Recordings - San Antonio, Texas) https://earthwalkerrecordings.bandcamp.com/album/floating-just-below-the-ice released December 31, 2017 Of Course It's All Things By Lowercase Noises https://open.spotify.com/album/5Z5ZCqsz4YM1W79aFyogU3 released January 1, 2018 Suites by Jan-Dirk Platek (Velbert, Germany) https://jan-dirkplatek.bandcamp.com/album/suites released January 1, 2018 Charred (single) by Giant Gutter From Outer Space (Muteant Sounds net label - Florida) https://muteantsoundsnetlabel.bandcamp.com/album/charred-single released January 1, 2018 Structure by Chvad SB (Silber Records - Sanford, North Carolina) https://silbermedia.bandcamp.com/album/structure released December 29, 2017 Winter EP '17 by Nonconnah (Silber Records - Sanford, North Carolina) https://silbermedia.bandcamp.com/album/winter- ep-17 released December 14, 2017 Everything by The American Dollar (New York) https://theamericandollar.bandcamp.com/track/everything released January 1, 2018 Akula by Akula (Columbus, Ohio) https://akulaband.bandcamp.com/releases released January 2, 2018 Music For An Unknown Galaxy -

DELAIN 12.05.2011 Stuttgart Die Röhre Mit Ihrem Euphorisch

DELAIN 12.05.2011 Stuttgart Die Röhre Mit ihrem euphorisch aufgenommenen Debüt „Lucidity“ konnten sich die niederländischen Gothmetaller von DELAIN im Jahr 2006 auf Anhieb in die Herzen der Fans und somit direkt in die erste Liga der harten Klänge spielen. Mit dem heiß erwarteten Nachfolger „April Rain“ legt die Formation um Frontfrau Charlotte Wessels und Band-Mastermind Martijn Westerholt nun ein mehr als beeindruckendes Zweitwerk vor, das die einschlägigen Haushalte trotz horrender Heizkostenabrechnungen bei Minustemperaturen definitiv auf Gotenmetal- Betriebstemperatur erwärmen wird! Nach einem unvermutet harten Winter lassen DELAIN nun endlich ihren belebenden „April Rain“ auf uns hernieder prasseln – atmosphärisch, lautmalerisch, symphonisch-erhaben und von einer faszinierend epischen Härte, die einen schon mit den ersten Klängen des selbst betitelten Openers unweigerlich in ihren Bann zieht. Glasklare Pianotröpfelchen entwickeln sich schon nach wenigen Sekunden zu einem reißenden Strom aus reiner Energie, welcher die Marschrichtung des neuen Outputs der ambitionierten Holländer unmissverständlich definiert: Immer weiter nach vorne; getrieben von der ganz eigenen Mischung aus heavy Riffing und einem sirenenhaften Gesang, der selbst die stolzesten Metallerherzen innerhalb eines Wimpernschlags von Elfenqueen Charlotte zum Schmelzen bringt. Was einst als reines Studioprojekt, gespickt mit vielen renommierten Stargästen, dafür aber ohne Aussicht auf irgendwelche Liveauftritte begonnen hatte, hat sich spätestens mit „April Rain“ zur waschechten Metalband aus fünf unterschiedlichen, miteinander interagierenden Charakteren gewandelt, die durch einen ewigen Bund miteinander verknüpft sind: Sich der Herausforderung zu stellen, das nach allen zur Verfügung stehenden Kräften beste Album aufzunehmen; ein – bei aller Konkurrenz und niederländischer Bescheidenheit – nicht gerade unsportliches Unterfangen. Nichts desto trotz stehen die Songs von „April Rain“ gerade in einer Zeit der Plagiatoren für sich selbst. -

Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks

common core state STANDARDs FOR english Language arts & Literacy in History/social studies, science, and technical subjects appendix B: text exemplars and sample Performance tasks Common Core State StandardS for engliSh language artS & literaCy in hiStory/SoCial StudieS, SCienCe, and teChniCal SubjeCtS exemplars of reading text complexity, Quality, and range & sample Performance tasks related to core standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that stu- dents should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: • Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on quali- tative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

Sun Signs (Linda Goodman)

Aries Leo Sagittarius March 21 - April 20 July 24 - Aug. 23 Nov. 23 - Dec. 21 Taurus Virgo Capricorn April 21 - May 21 Dec. 22 - Jan. 20 Aug 24 - Sept. 23 Gemini Libra Aquarius May 22 - June 21 Sept. 24 - Oct. 23 Jan. 21 - Feb. 19 Cancer Scorpio Pisces June 22 - July 23 Oct. 24 - Nov. 22 Feb. 20 - Mar. 20 CONTENTS Foreword HOW TO UNDERSTAND SUN SIGNS ARIES the Ram March 21st through April 20th How to Recognize ARIES The ARIES Man The ARIES Woman The ARIES Child The ARIES Boss The ARIES Employee TAURUS the Bull April 21st through May 21st How to Recognize TAURUS The TAURUS Man The TAURUS Woman The TAURUS Child The TAURUS Boss The TAURUS Employee GEMINI the Twins May 22nd through June 21st How to Recognize GEMINI The GEMINI Man The GEMINI Woman The GEMINI Child The GEMINI Boss The GEMINI Employee CANCER the Crab June 22nd through July 23rd How to Recognize CANCER The CANCER Man The CANCER Woman The CANCER Child The CANCER Boss The CANCER Employee LEO the Lion July 24th through August 23rd How to Recognize LEO The LEO Man The LEO Woman The LEO Chid The LEO Boss The LEO Employee VIRGO the Virgin August 24th through September 23rd How to Recognize VIRGO The VIRGO Man The VIRGO Woman The VIRGO Child The VIRGO Boss The VIRGO Employee rLIBRA the Scales September 24th through October 23rd How to Recognize LIBRA The LIBRA Man The LIBRA Woman The LIBRA Child The LIBRA Boss The LIBRA Employee SCORPIO the Scorpion, Eagle or Gray Lizard October 24th through November 22nd How to Recognize SCORPIO The SCORPIO Man The SCORPIO Woman The SCORPIO Child The -

Playlists: April 2010-June 2010

“Assume The Position” Playlists: April 2010-June 2010 Date: SUNDAY APRIL 4 2010 TIME: 22:00-00:00 120:00 ARTIST TITLE ALBUM/YEAR TIME 1. AC/DC Shoot To Thrill Iron Man 2 (2010) 5:19 2. ALICE COOPER Fantasy Man Dragontown (2001) 4:05 3. DAN REED Tiger In A Dress Slam (1988) 5:26 4. STAGE DOLLS Rainin’ On A Sunny Day Always (2010) 4:04 5. UFO Can’t Buy A Thrill The Visitor (2009) 5:14 6. GENESIS Turn It On Again Duke (1980) 3:52 7. FM Still The Fight Goes On Metropolis (2010) 7:10 8. ELEKTRADRIVE You Are Always On My Mind Living 4 (2009) 5:27 9. DARE Follow The River Arc Of The Dawn (2009) 3:36 10. JUDIE TZUKE If (When You Go) Moon On A Mirrorball (2010) 4:07 11. LISBEE STAINTON Just Like Me Girl On An Unmade Bed (2009) 2:49 12. NATASCHA SOHL Fade Single (2010) 4:01 13. JOHN ILLSLEY Is It Real Streets Of Heaven (2010) 4:21 14. STEVE VAI For The Love Of God Where The Other Wild Things Are 10:38 (2010) 15. EXTREME Get The Funk Out Take Us Alive (2010) 6:52 16. SILENT CALL Every Day Greed (2010) 5:41 17. DEEP PURPLE Black Night (live) Singles & EP Anthology (2010) 4:55 18. BLACK SABBATH The Mob Rules Mob Rules (2010) 3:14 19. WINGER Battle Stations Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991) 3:58 20. WINGER Someday Someway Demo Anthology (2007) 4:16 21. WINGER Headed For A Heartbreak Winger (1988) 5:13 22. -

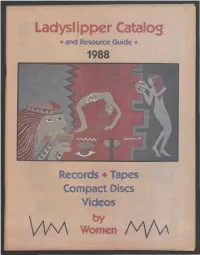

Ladyslipper Catalog • and Resource Guide • 1988

Ladyslipper Catalog • and Resource Guide • 1988 Records • Tapes Compact Discs Videos V\M Women Mf\A About Ladyslipper Ladyslipper is a North Carolina non-profit, tax- 1982 brought the first release on the Ladys exempt organization which has been involved lipper label Marie Rhines/Tartans & Sagebrush, in many facets of women's music since 1976. originally released on the Biscuit City label. In Our basic purpose has consistently been to 1984 we produced our first album, Kay Gard heighten public awareness of the achievements ner/A Rainbow Path. In 1985 we released the of women artists and musicians and to expand first new wave/techno-pop women's music al the scope and availability of musical and liter bum, Sue Fink/Big Promise; put the new age ary recordings by women. album Beth York/Transformations onto vinyl; and released another new age instrumental al One of the unique aspects of our work has bum, Debbie Fier/Firelight. Our purpose as a been the annual publication of the world's most label is to further new musical and artistic direc comprehensive Catalog and Resource Guide of tions for women artists. Records and Tapes by Women—the one you now hold in your hands. This grows yearly as Our name comes from an exquisite flower the number of recordings by women continues which is one of the few wild orchids native to to develop in geometric proportions. This anno North America and is currently an endangered tated catalog has given thousands of people in species. formation about and access to recordings by an expansive variety of female musicians, writers, Donations are tax-deductible, and we do need comics, and composers. -

Haute Frequence

Oum HAUTE FREQUENCE SONIC CITY / HEARTBEATS / LES NUITS ELECTRIQUES MAGAZINE MUSICAL GRATUIT / ILLICO! 17 NOV 2016 BREF! 4 ACTU DES SALLES 6 AERONEF / EL DIABLO 6 PENICHE / CCGP CALAIS 8 GRAND MIX / 4 ECLUSES 10 PICARDIE EXPRESS 12 HAUTE FREQUENCE 16 CAVE AUX POETES / ANTRE 2 13 LE FLOW 12 LE MANEGE / METAPHONE 14 CONCERTS & FESTIVALS 16 HAUTE FREQUENCE 16 LES NUITS ELECTRIQUES 18 CHRISTINE SALEM 19 HEARTBEATS 20 LA NUIT DU BLUES 21 SONIC CITY 22 CHILDREN OF... 23 ROUND THE WORLD OF SOUND 24 SEA SONG(E) / DUKE ROBILLARD 25 JAMES HUNTER 26 INGRID LAUBROCK ANTI-HOUSE 27 LES NUITS ELECTRIQUES 18 CLUB PLASMA / KVELERTAK 28 TOUR DE FLOW / MESPARROW 30 FABLES DE JEAN DE LES EGOUTS 32 DIRTY SHIRT 33 ARKAN / INQUISITION 34 DAPHNE SWAN / DELAIN 36 LIFE OF AGONY / WAND 38 PSYKOKONDRIAK 40 JAGWAR MA / LESCOP 41 GIEDRE / IMPERIAL CROWNS 42 ROUBAIX VINTAGE WEEKENDER 44 VU EN OCTOBRE 46 AGENDA 48 INDEX DES SALLES 61 HEARTBEATS 20 Édité par MANICRAC DIFFUSION C*RED. REDACTEURS Guillaume A, aSk, Yann Association loi 1901 à but non lucratif. AUBERTOT, Benjamin BUISINE, Guillaume Merci à tous nos diffuseurs pour la CANTALOUP, Claude COLPAERT, Patrick Dépôt légal : à parution diffusion en région. DALLONGEVILLE, Selector DDAY, Tirage : 15 000 exemplaires. Vincent DEMARET, Ricardo DESOMBRE, JITY, Senor KEBAB, Maryse LALOUX, REDACTION Bertrand LANCIAUX, Raphaël LOUVIAU, SIEGE SOCIAL TEL : 06 62 71 47 38 Luiz MICHEL, Olivier PARENTY, Romain 6 rue Wulverick 59160 LOMME [email protected] [email protected] RICHEZ, SCHNAPS, Mathy, Grégory SMETS, Sylvain STRICANNE, Nicolas DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION SWIERCZEK. PUBLICITE Samuel SYLARD Samuel SYLARD Tel : 06 62 71 47 38 Photo couverture : OUM [email protected] SECRÉTAIRE DE RÉDACTION © Lamia LAHBABI Bertrand LANCIAUX IMPRIMERIE Prochain numéro Samedi 3 Décembre MORDACQ Aire sur la Lys (62) MISE EN PAGE Samuel SYLARD www.illicomag.fr 3 • ILLICO! 17 • NOVEMBRE 2016 CAYMAN KINGS LIV[R]E CONFERENCE ROCK’N NOEL ART’TRANS #1 LIVE ENTRE LES LIVRES Depuis sa naissance, le Vous connaissez le ART’TRANS est un mini festival à la campagne. -

Delain the Human Contradiction Mp3, Flac, Wma

Delain The Human Contradiction mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Human Contradiction Country: Austria Released: 2014 Style: Heavy Metal, Symphonic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1445 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1655 mb WMA version RAR size: 1720 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 750 Other Formats: FLAC RA AC3 AHX ADX DTS AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Here Comes The Vultures 6:05 Your Body Is A Battleground A2 3:50 Vocals – Marco Hietala A3 Stardust 3:57 A4 My Masquerade 3:43 Tell Me, Mechanist A5 4:52 Vocals [Grunts] – George Oosthoek Sing To Me B1 5:09 Vocals – Marco Hietala B2 Army Of Dolls 4:57 B3 Lullaby 4:56 The Tragedy Of The Commons B4 4:31 Vocals [Grunts] – Alissa White-Gluz C1 Scarlet 4:36 C2 Don't Let Go 3:57 C3 My Masquerade (Live At The My Masquerade Concert 2013) 5:01 C4 April Rain (Live At The My Masquerade Concert 2013) 4:46 D1 Go Away (Live At The My Masquerade Concert 2013) 3:42 D2 Sever (Live At The My Masquerade Concert 2013) 4:54 D3 Stay Forever (Live At The My Masquerade Concert 2013) 4:32 D4 Sing To Me (Orchestra) 3:43 D5 Your Body Is A Battleground (Orchestra) 3:21 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Napalm Records Handels GmbH Copyright (c) – Napalm Records Handels GmbH Published By – Copyright Control Credits Bass – Otto Schimmelpenninck van der Oije Drums – Sander Zoer Guitar – Timo Somers Keyboards – Martijn Westerholt Lead Vocals – Charlotte Wessels Notes Strictly Limited to 100 copies Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8 19224 01838 4 Matrix / Runout (Side A): NAPALM RECORDS NPR 535LP -

Delain Mp3 Torrent Download Delain – Apocalypse & Chill (2020) Zip Torrent, Zippyshare

delain mp3 torrent download Delain – Apocalypse & Chill (2020) zip Torrent, Zippyshare. Delain – Apocalypse & Chill (2020) Album Leak zip 320 kbps mp3 m4a Mediafire Free. Delain – Apocalypse & Chill (2020) rar Full Album 320 kbps. TRACKLIST: 01 – One Second 02 – We Had Everything 03 – Chemical Redemption 04 – Burning Bridges 05 – Vengeance 06 – To Live Is to Die 07 – Let’s Dance 08 – Creatures 09 – Ghost House Heart 10 – Masters of Destiny 11 – Legions of the Lost 12 – The Greatest Escape 13 – Combustion. Delain - Дискография (2002-2019) 01 - Sever 02 - Frozen 03 - Silhouette Of A Dancer 04 - No Compliance 05 - See Me In Shadow 06 - Shattered 07 - The Gathering 08 - Daylight Lucidity 09 - Sleepwalkers Dream 10 - A Day For Ghosts 11 - Pristine 12 - (Deep) Frozen (Bonus Track) 13 - Frozen (acoustic) [bonus track] 14 - Silhouette Of A Dancer (acoustic) [bonus track] 15 - See Me In Shadow (acoustic) [bonus track] 16 - No Compliance (Charlotte vocals) [bonus track] 2006 - Shattered (Single) (320 kbps) (04:20) 2007 - Frozen (Single) (320 kbps) (08:46) 01. Frozen (Single Version) 02. (Deep) Frozen. 2007 - See Me in Shadow (Single) (320 kbps) (15:15) 01. See me in shadow (Single version) 02. Frozen (Acoustic) 03. Silhouette of a dancer (Acoustic) 04. See me in shadow (Acoustic) 2008 - The Gathering (Single) (320 kbps) (06:45) 01. The Gathering (Radio Version) 02. The Gathering (Album Version) 2009 - April Rain (Single) (320 kbps) (08:15) 01. April Rain (edit version) 02. April Rain (album version) 2009 - April Rain (320 kbps) (55:32) 01. April Rain 02. Stay Forever 03. Invidia 04. Control The Storm 05.