GERTRUD PFISTER Sportification, Power, and Control: Ski-Jumping As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flow Over a Ski Jumper in Flight

Journal of Biomechanics 89 (2019) 78–84 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Biomechanics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jbiomech www.JBiomech.com Flow over a ski jumper in flight: Prediction of the aerodynamic force and flight posture with higher lift-to-drag ratio ⇑ Woojin Kim a, Hansol Lee b, Jungil Lee c, Daehan Jung d, Haecheon Choi a,b, a Institute of Advanced Machines and Design, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Republic of Korea b Department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Republic of Korea c Department of Mechanical Engineering, Ajou University, Suwon 16499, Republic of Korea d Department of Mechanical Engineering, Korea Air Force Academy, Cheongju 28187, Republic of Korea article info abstract Article history: Large eddy simulations (LESs) are performed to study the flow characteristics around two flight posture Accepted 12 April 2019 models of ski jumping. These models are constructed by three-dimensionally scanning two national- team ski jumpers taking flight postures. The drag and lift forces on each component of a ski jumper and skis (head with helmet and goggle, body, arms, legs and skis) and their lift-to-drag ratios are Keywords: obtained. For the two posture models, the drag forces on the body, legs and skis are larger than those Ski jumping on the arms and head with helmet and goggle, but the lift forces on the body and skis are larger than their Flight posture drag forces, resulting in high lift-to-drag ratios on the body and skis and low lift-to-drag ratio on the legs. -

Lesson Number Five : Snow Sports 1- Ski Flying : Is a Winter Sport Discipline Derived from Ski Jumping, in Which Much Greater Distances Can Be Achieved

Lesson number five : Snow sports 1- Ski flying : is a winter sport discipline derived from ski jumping, in which much greater distances can be achieved. It is a form of competitive individual Nordic skiing where athletes descend at very fast speeds along a specially designed takeoff ramp using skis only; jump from the end of it with as much power as they can generate; then glide – or 'fly' – as far as possible down a steeply sloped hill; and ultimately land within a target zone in a stable manner. Points are awarded for distance and stylistic merit by five judges, and events are governed by the International Ski Federation (Fédération Internationale de Ski; FIS). 2- Snowshoe running : or snowshoeing, is a winter sport practiced with snowshoes, which is governed by World Snowshoe Federation (WSSF) founded in 2010, which until 2015 had its name International Snowshoe Federation (ISSF). The snowshoes running is part of the Special Olympics and Arctic Winter Games programs. 5- Skiboarding is a type of freestyle skiing using short, usually double-tipped skis, regular ski boots and bindings, and no poles. It is also known as snowblading or skiblading. It is a recreational sport with no governing body or competition. The first mass produced skiboard was the Austrian Kneissl Bigfoot in 1991. American manufacturers such as Line Skis then began to produce skiboards, and the sport grew in popularity. From 1998 to 2000, skiboarding was part of the winter X Games in the slopestyle event. After it was dropped there was no longer a profession circuit for the sport, and many competitors switched to freestyle skiing on twin-tip skis. -

Olympic Team Norway

Olympic Team Norway Media Guide Norwegian Olympic Committee NORWAY IN 100 SECONDS NOC OFFICIAL SPONSORS 2008 SAS Braathens Dagbladet TINE Head of state: Adidas H.M. King Harald V P4 H.M. Queen Sonja Adecco Nordea PHOTO: SCANPIX If... Norsk Tipping Area (total): Gyro Gruppen Norway 385.155 km2 - Svalbard 61.020 km2 - Jan Mayen 377 km2 Norway (not incl. Svalbard and Jan Mayen) 323.758 km2 Bouvet Island 49 km2 Peter Island 156 km2 NOC OFFICIAL SUPPLIERS 2008 Queen Maud Land Population (24.06.08) 4.768.753 Rica Hertz Main cities (01.01.08) Oslo 560.484 Bergen 247.746 Trondheim 165.191 Stavanger 119.586 Kristiansand 78.919 CLOTHES/EQUIPMENTS/GIFTS Fredrikstad 71.976 TO THE NORWEGIAN OLYMPIC TEAM Tromsø 65.286 Sarpsborg 51.053 Adidas Life expectancy: Men: 77,7 Women: 82,5 RiccoVero Length of common frontiers: 2.542 km Silhouette - Sweden 1.619 km - Finland 727 km Jonson&Jonson - Russia 196 km - Shortest distance north/south 1.752 km Length of the continental coastline 21.465 km - Not incl. Fjords and bays 2.650 km Greatest width of the country 430 km Least width of the country 6,3 km Largest lake: Mjøsa 362 km2 Longest river: Glomma 600 km Highest waterfall: Skykkjedalsfossen 300 m Highest mountain: Galdhøpiggen 2.469 m Largest glacier: Jostedalsbreen 487 km2 Longest fjord: Sognefjorden 204 km Prime Minister: Jens Stoltenberg Head of state: H.M. King Harald V and H.M. Queen Sonja Monetary unit: NOK (Krone) 16.07.08: 1 EUR = 7,90 NOK 100 CNY = 73,00 NOK NORWAY’S TOP SPORTS PROGRAMME On a mandate from the Norwegian Olympic Committee (NOK) and Confederation of Sports (NIF) has been given the operative responsibility for all top sports in the country. -

National Sports Federations (Top Ten Most Funded Olympic Sports)

National Sports Federations (top ten most funded Olympic sports) Coverage for data collection 2020 Country Name of federation EU Member States Belgium (French Community) Associations clubs francophones de Football Association Francophone de Tennis Ligue Belge Francophone d'Athlétisme Association Wallonie-Bruxelles de Basket-Ball Ligue Francophone de Hockey Fédération francophone de Gymnastique et de Fitness Ligue Francophone de Judo et Disciplines Associées Ligue Francophone de Rugby Aile francophone de la Fédération Royale Belge de Tennis de Table Ligue équestre Wallonie-Bruxelles Belgium (Flemish Community) Voetbal Vlaanderen Gymnastiekfederatie Vlaanderen Volley Vlaanderen Tennis Vlaanderen Wind en Watersport Vlaanderen Vlaamse Atletiekliga Vlaamse Hockey Liga Vlaamse Zwemfederatie Cycling Vlaanderen Basketbal Vlaanderen Belgium (German Community) Verband deutschsprachiger Turnvereine Interessenverband der Fußballvereine in der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Ostbelgischer Reiterverband Ostbelgischer Tischtennisverband Regionaler Sportverband der Flachbahnschützen Ostbelgiens Regionaler Tennisverband der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Verband Ostbelgischer Radsportler Taekwondo verband der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Ostbelgischer Ski- und Wintersportverband Regionaler Volleyballverband VoG Bulgaria Bulgarian Boxing Federation Bulgarian Ski Federation Bulgarian Gymnastics Federation Bulgarian Wrestling Federation Bulgarian Volleyball Federation Bulgarian Weightlifting Federation Bulgarian Judo Federation Bulgarian Canoe-Kayak Federation -

Fis World Cup Nordic Skiing Holmenkollen 2012

INVITATION FIS WORLD CUP NORDIC SKIING HOLMENKOLLEN 2012 HOLMENKOLLEN-WORLDCUP.NO FIS World Cup FIS World Cup Sponsors Official Timing Event Sponsors FIS World Cup FIS World Cup Sponsor Event Sponsor FIS World Cup FIS World Cup Sponsor Event Sponsors FIS World Cup Event Sponsor LADIES INVITATION TO FIS WORLD CUP NORDIC SKIING, 9-11 MARCH 2012 On behalf of the International Ski Federation (FIS) and the Norwegian Ski Federation (NSF) the Organising Committee for the 2012 FIS World Cup Nordic Skiing in Holmenkollen has the pleasure of inviting the National Ski Associations (NSA) to the FIS World Cup Nordic Skiing in Holmenkollen 9-11 March, 2012. With an experienced staff of officials and volunteers we will do our utmost to provide good and fair conditions for the athletes. We look forward to see you back in the famous Holmenkollen arena in March 2012 – together with our large and enthusiastic spectator crowds! Per Bergerud John Aalberg Chairman of the Board Admin. Director of Events 2012 FIS World Cup Nordic, Holmenkollen GENERAL INFORMATION Accreditation Accreditations will be available in the Service Centre at Holmenkollen Park Hotel Rica adjacent to the venue. The Cross-Country Teams will use their FIS season accreditation. Competiton Rules The competitions will be held in compliance with FIS International Competition Rules and World Cup Rules. Doping Control Anti-doping testing may take place during the event according to FIS rules. Insurance All the athletes have to be insured through their National Ski Associations. The organiser is not responsible for any injury to person or damage to property. -

Willinger Weltcup in Zahlen Vor Springen Nummer 50 Und 51 Seit 1995

Willinger Weltcup in Zahlen Vor Springen Nummer 50 und 51 seit 1995 3 Mal stand Olympiasieger Kamil Stoch (Polen) nach den Einzelspringen auf der Mühlenkopfschanze schon ganz oben auf dem Treppchen. Damit ist er gemeinsam mit Noriaki Kasai Rekordhalter. Beide gewannen in Willingen auch schon mit ihrem Team, Stoch auch die Premiere von „Willingen Five“ 2018. 7 DSV-Adler standen mit Sven Hannawald (2002 und 2003), Severin Freund (2011 und 2015), Andreas Wellinger (2017). Karl Geiger (2019) und Stephan Leyhe beim Kult- Willinger Weltcup als Sieger auf dem Podest. Dazu kamen drei deutsche Siege in den Teamwettbewerben (2005, 2010, 2016). Sieben Einzelsiege haben auch die österreichischen „Adler“ seit Beginn der Weltcupspringen in Willingen im Jahr 1995 errungen: Schlierenzauer (2010 und 2009), Kofler (2006), Widhölzl (2x 2000), Höllwarth (1997) und Goldberger (1995). Damit sind sie gemeinsam mit Deutschland die erfolgreichste Nation vor Polen, Norwegen und Japan mit je vier Siegen. 17 Team-Weltcups fanden bisher im Waldecker Upland statt. Österreich (4), Deutschland und Norwegen (je 3), Polen, Finnland und Slowenien (je 2) sowie Japan trugen sich dabei in die Siegerliste am Mühlenkopf ein. 21 DSV-Adler haben bisher in Willingen auf dem Weltcup-Treppchen gestanden Spitzenreiter sind Severin Freund (11), Martin Schmitt (8), Richard Freitag (7), Michael Uhrmann (6) sowie Dieter Thoma, Sven Hannawald, Michael Neumayer und Andreas Wellinger (je 4). 49 Weltcup-Konkurrenzen sind seit 1995 insgesamt im Strycktal ausgetragen worden. Österreich (11 Siege) führt die Erfolgsserie vor Deutschland (10) und Norwegen (8) an, dahinter folgen Japan und Polen (je 6), Finnland (5) sowie Slowenien (3) an. Die Nummer 50 und 51 stehen vom 29. -

A Trusted Partner Why Nammo?

Nammo aNNual 12 RepoRt A trusted partner Why Nammo? “ Nammo, with itsvalue-based company culture and way of doing business, is an excellent partner in our efforts to develop a strong and healthy culture in Norwegian ski jumping, where a good attitude and way of living our values is the foundation for our performanceculture. – Clas Brede Bråthen, Director Ski Jumping, Norwegian Ski Federation – A trusted partner Nammo’s values Dedication We are enthusiastic and creative, always searching for the best solutions Precision We are reliable and accurate in our technology, processes and business Care We are inclusive and open-minded, always encouraging team spirit and cooperation Nammo in brief The Nammo Group, headquartered in Raufoss, Norway, is a technology driven aerospace and defense group specializing in high-end products. Core business comprised of commercial sales of services The core business of the Nammo Group is and sports and security products. the development, testing, production and sale of military and sport ammunition, Organization shoulder launched weapons systems, Nammo is present in eight countries with rocket motors for military and space a total of 18 production sites and sales applications and leading global services for offices. The group operates through its five environmentally friendly demilitarization. business units: Small Caliber, Medium & Large Caliber, Missile Products, Demil and Customer base Nammo Talley. As a technology driven aerospace and defense group, the majority of Nammo’s Ownership business is with the national armed forces The Nammo Group’s shareholders are or the national defense industries in the the Norwegian Ministry of Trade and countries where we operate. -

Constance, GER, November 2019

To the INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION - Members of the FIS Council Blochstrasse 2 - National Ski Associations 3653 Oberhofen/Thunersee - Committee Chairs Switzerland Tel +41 33 244 61 61 Fax +41 33 244 61 71 Oberhofen, 26th November 2019 Summary of the FIS Council Meeting, 23rd November 2019, Konstanz / Constance (GER) Dear President, Dear Ski Friends, In accordance with art. 32.2 of the FIS Statutes we have pleasure in sending you the Summary of the most important decisions from the FIS Council Meeting which took place on 23rd November 2019 in Constance (GER). 1. Members present The following elected Council Members were present at the meeting in Constance (GER) on Saturday, 23rd November 2019: President Gian Franco Kasper, Vice-Presidents Mats Arjes, Janez Kocijancic and Aki Murasato, Members: Steve Dong Yang, Dean Gosper, Alfons Hörmann, Hannah Kearney (Athletes’ Commission Representative), Roman Kumpost, Dexter Paine, Flavio Roda, Erik Roeste, Konstantin Schad (Athletes’ Commission Representative), Peter Schröcksnadel, Martti Uusitalo, Eduardo Valenzuela and Michel Vion, Secretary General Sarah Lewis Apologies: Vice-President Patrick Smith, Council Member Andrey Bokarev Honorary Members: Sverre Seeberg, Carl-Eric Stalberg, Hank Tauber Guest: Franz Steinle President German Ski Association Observer: Dave Pym (CAN) representing Patrick Smith Experts: Stephan Netzle, Legal Counsel; Erwin Lauterwasser, Environment 2. Minutes from the Council Meeting in Cavtat-Dubrovnik (CRO) June 2019 The Summary and Minutes from the Council Meetings in -

STATS EN STOCK Les Palmarès Et Les Records

STATS EN STOCK Les palmarès et les records Jeux olympiques d’hiver (1924-2018) Depuis leur création en 1924, vingt-trois éditions des Jeux olympiques d’hiver se sont déroulées, regroupant des épreuves aussi variées que le ski alpin, le patinage, le biathlon ou le curling. Et depuis la victoire du patineur de vitesse Américain Jewtraw lors des premiers Jeux à Chamonix, ce sont plus de mille médailles d’or qui ont été attribuées. Charles Jewtraw (Etats-Unis) Yuzuru Hanyu (Japon) 1er champion olympique 1000e champion olympique (Patinage de vitesse, 500 m, 1924) (Patinage artistique, 2018) Participants Année Lieu Nations Epreuves Total Hommes Femmes 1924 Chamonix (France) 16 258 247 11 16 1928 St Moritz (Suisse) 25 464 438 26 14 1932 Lake-Placid (E-U) 17 252 231 21 17 1936 Garmish (Allemagne) 28 646 566 80 17 1948 St Moritz (Suisse) 28 669 592 77 22 1952 Oslo (Norvège) 30 694 585 109 22 1956 Cortina d’Ampezzo (Italie) 32 821 687 134 24 1960 Squaw Valley (E-U) 30 665 521 144 27 1964 Innsbruck (Autriche) 36 1 091 892 199 34 1968 Grenoble (France) 37 1 158 947 211 35 1972 Sapporo (Japon) 35 1 006 801 205 35 1976 Innsbruck (Autriche) 37 1 123 892 231 37 1980 Lake Placid (E-U) 37 1 072 840 232 38 1984 Sarajevo (Yougoslavie) 49 1 272 998 274 39 1988 Calgary (Canada) 57 1 423 1 122 301 46 1992 Albertville (France) 64 1 801 1 313 488 57 1994 Lillehammer (Norvège) 67 1 737 1 215 522 61 1998 Nagano (Japon) 72 2 176 1 389 787 68 2002 Salt Lake City (E-U) 77 2 399 1 513 886 78 2006 Turin (Italie) 80 2 508 1 548 960 84 2010 Vancouver (Canada) 82 2 566 -

Green Champions in Sport and Environment

Guide to environmentally-sound large sporting events Green Champions in Sport and Environment Publishers German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety German Olympic Sports Confederation 2 Guide Green Champions Editorial note „Green Champions in Sport and Envi- The guide is aimed, above all, at the ronment“ is published by the German organizers of large sporting events. It Federal Ministry for the Environment, is also directed, however, at national Nature Conservation and Nuclear and international sports associa- Safety and the German Olympic tions, since these set the framework Sports Confederation. The many ex- through the demands they make on amples of good practices that it con- events, through contracts with spon- tains therefore relate to action taken sors and through their competition in Germany. They demonstrate that rules. Organizers can only operate a number of measures have already within these limits, and this applies been implemented at large sporting also to the development and imple- events and are therefore feasible. mentation of environmental concepts. Comparable initiatives have also been The guide wishes, in particular, to taken in other countries. The German encourage sports associations to examples of good practice are merely examine how the framework for envi- representative. ronmentally favourable large sporting events can be further improved. Moreover, the recommendations for action put forward in the guide In order that there be even more are implementable in every country. green champions in sport and They apply – taking into considera- environment in the future, national tion respective local conditions – to and international sports associa- a Football World Cup in Germany as tions should also link the awarding well as to a World Cup in South Af- of events to ecological demands. -

International Ski Federation (FIS)

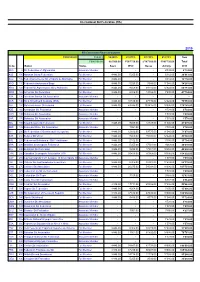

International Ski Federation (FIS) 2019 FIS Calculation Financial Support 5'000'000.00 100.00% 12.500% 21.875% 43.750% 21.875% New 5'000'000.00 625'000.00 1'093'750.00 2'187'500.00 1'093'750.00 Total Code Nation Status Basic WSC Races Activity 2019 AFG 0 Ski Federation of Afghanistan Associate Member - - - 4'734.00 4'734.00 ALB 100 Albanian Skiing Federation Full Member 8'446.00 5'255.00 - 6'312.00 20'013.00 ALG 105 Féd. Algérienne de Ski et Sports de Montagne Full Member 8'446.00 - - 6'312.00 14'758.00 AND 110 Federació Andorrana d'Esquí Full Member 8'446.00 5'255.00 9'546.00 11'046.00 34'293.00 ARG 120 Federación Argentina de Ski y Andinismo Full Member 8'446.00 9'459.00 38'184.00 12'624.00 68'713.00 ARM 125 Armenian Ski Federation Full Member 8'446.00 6'306.00 19'092.00 7'890.00 41'734.00 ASA 130 American Samoa Ski Association Associate Member - - - - - AUS 140 Ski & Snowboard Australia (SSA) Full Member 8'446.00 10'510.00 47'730.00 12'624.00 79'310.00 AUT 150 Österreichischer Skiverband Full Member 8'446.00 48'346.00 103'415.00 18'936.00 179'143.00 AZE 160 Azerbaijan Ski Federation Associate Member - - - 4'734.00 4'734.00 BAH 190 Bahamas Ski Association Associate Member - - - 1'578.00 1'578.00 BAR 170 Barbados Ski Association Associate Member - - - 1'578.00 1'578.00 BEL 180 Royal Belgian Ski Federation Full Member 8'446.00 9'459.00 12'728.00 11'046.00 41'679.00 BER 185 Bermuda Winter Ski Association Associate Member - 1'051.00 - 4'734.00 5'785.00 BIH 200 Ski Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina Full Member 8'446.00 12'612.00 39'775.00 11'046.00 71'879.00 BLR 210 Belarus Ski Union Full Member 8'446.00 8'408.00 15'910.00 12'624.00 45'388.00 BOL 220 Federacion Boliviana de Ski Y Andinismo Full Member 8'446.00 2'102.00 - 3'156.00 13'704.00 BRA 230 Brazilian Snow Sports Federation Full Member 8'446.00 5'255.00 17'501.00 9'468.00 40'670.00 BUL 240 Bulgarian Ski Federation Full Member 8'446.00 9'459.00 17'501.00 14'202.00 49'608.00 CAN 250 Canadian Snowsports Association CSA Full Member 8'446.00 30'479.00 76'368.00 18'936.00 134'229.00 CAY 255 Cayman Islands Conf. -

Andreas Goldberger, Austria

ANDREAS GOLDBERGER, AUSTRIA PRESENTED THROUGH THE CHRONOLOGICAL OVERVIEW AND STATISTICAL SUMMARY OF ALL MAJOR TOP ACHIEVEMENTS IN HIS SKI JUMPING CAREER TYPES OF COMPETITIONS: World Cup (WCup) Olympic Winter Games (OWG) Nordic World Ski Championships (NWSC) Ski Flying World Championships (SFWC) ====================================================================================================================================================================================== Innsbruck, Austria Oberstdorf, Germany Harrachov, Czechoslov. Harrachov, Czechoslov. * SKI FLYING STANDING Falun, Sweden Oberstdorf, Germany 4. January 1992 (L): 26. January 1992 (F): 22. March 1992 (F): 22. March 1992 (F): Season 1991/1992: 6. December 1992 (L): 30. December 1992 (L): 1. Toni Nieminen, Fin 1. Werner Rathmayr, Aut 1. Noriaki Kasai, Jpn 1. Noriaki Kasai, Jpn 1. Werner Rathmayr, Aut 1. Werner Rathmayr, Aut 1. Christof Duffner, Ger 2. Andr. Goldberger, Aut 2. Andreas Felder, Aut 2. Andr. Goldberger, Aut 2. Andr. Goldberger, Aut 2. Andr. Goldberger, Aut 2. Andr. Goldberger, Aut 2. Andr. Goldberger, Aut 3. Andreas Felder, Aut 3. Andr. Goldberger, Aut 3. Roberto Cecon, Ita 3. Roberto Cecon, Ita 3. Andreas Felder, Aut Lasse Ottesen, Nor 3. Noriaki Kasai, Jpn -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------