How to Get Home from Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

270 Songs, 17.5 Hours, 1.62 GB Page 1 of 8 Name BPM Genre Rating

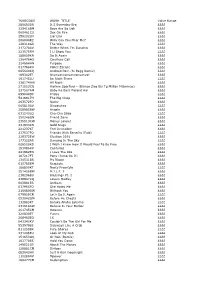

Page 1 of 8 WCS 270 songs, 17.5 hours, 1.62 GB Name BPM Genre Rating Artist Album Year Freezing 76 Pop Music Mozella Belle Isle (Deluxe… 2010 Thinking Out Loud 79 Pop Ballad Ed Sheeran x 2014 I'm So Miserable 83 Country Billy Ray Cyrus Some Gave All 1992 Too Darn Hot (RAC Mix) 83 R&B Ella Fitzgerald Verve Remixed: T… 2013 Feelin' Love 83 Blues Paula Cole City of Angels OST 1998 I'm Not the Only One 83 Pop Ballad Sam Smith In the Lonely Hou… 2014 Free 84 R&B Haley Reinhart Listen Up! 2012 Stompa 84 Alt Pop Serena Ryder Harmony 2012 Treat You Better 84 Pop Music Shawn Mendes Illuminate 2016 Heartbreak Road 85 Blues Rock Colin James Hearts on Fire 2015 Shape of My Heart 85 Rock Ballad Theory of a Deadman Shape of My Hear… 2017 Gold 86 Pop Music Kiiara low kii savage - EP 2015 I'm the Only One 87 Blues Rock Melissa Etheridge Yes I Am 1993 Rude Boy 87 Pop Music Rihanna Rated R 2009 Then 88 Pop Music Anne-Marie Speak Your Mind 2017 Can't Stay Alone Tonight 88 Pop-Rock Elton John The Diving Board… 2013 Vinyl (Remix) 88 Jazz-Pop Euge Groove feat. x-t.o.p. Sax S Euge Groove 2000 Wake Up Screaming 88 Country Gary Allan Used Heart For Sale 2000 Anything's Possible 88 R&B Jonny Lang Turn Around 2006 Slow Hands 88 Pop Music Niall Horan Slow Hands - Sin… 2017 Touch Of Heaven 88 Pop-Rock Richard Marx Flesh & Bone 1997 Forever Drunk 89 R&B Miss Li Beats & Bruises 2011 Let's Get Back To Bed Boy 89 R&B Sarah Connor Green Eyed Soul 2002 I Can't Stand the Rain 89 Pop-Soul Seal Soul 2008 Happy 90 R&B Ashanti Ashanti 2002 Mood For Luv 90 R&B B.B. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Section 10: Outdoor Action Song Guide

Section 10: Outdoor Action Song Guide Songs, just like games, can be a useful and fun addition to a trip. Whether used to get the group warmed up on a chilly morning or to lighten the mood on the trail, songs should be a part of your leader bag of tricks. Most of these songs represent relatively low interpersonal risk except for songs that single out individuals such as Little Sally Walker. As for any activity, use your leader radar to determine when the individual and group dynamics are appropriate for a particular song. Enjoy! 10-1 Old Nassau Tune every heart and every voice, bid every care withdraw; Let all with one accord rejoice, in praise of Old Nassau. In praise of Old Nassau we sing, Hurrah! hurrah! hurrah! Our hearts will give while we shall live, three cheers for Old Nassau. 10-2 10-3 10-4 10-5 10-6 10-7 10-8 Go Bananas CHORUS (With Actions) LEADER: Bananas of the world…UNITE! Thumbs up! Elbows back! LEADER: Bananas…SPLIT! Thumbs up! Elbows back! Knees together! Toes together ALL: Peel bananas, peel peel bananas Butt out Slice bananas… Head out Mash bananas… Spinning round Dice bananas… Tongue out Whip bananas… Jump bananas… GO BANANAS… The Jellyfish (Jellyfish should be yelled in silly voice to yield its full comedic effect.) CHORUS Penguin Song ALL: The jellyfish, the jellyfish, the jellyfish (while (With Actions) moving like a jellyfish). CHORUS ALL: Have you ever seen a penguin come to tea? LEADER: Feet together!! Take a look at me, a penguin you will see ALL: Feet together!! Penguins attention! Penguins begin! (Salute here) -

The Pioneer and the Savage

The Pioneer and The Savage a novel Jamie Thorogood Badley Project 2020 8th April 2020 Foreword For my Badley Project this year I have written a novel. I started thinking about The Pioneer and the Savage a couple of years ago, but only this year did I actually sit down and write it. It’s been an amazing experience to plan, write and bind, and something I’ll remember for a while. In this story I tried to address the issues of racism, sexism and living alongside – and respecting – nature. It follows the adventures of Piper Morning, a small-minded girl who travels to an island far away with her father. She meets a young, native boy and a friendship forms. It is 67,068 words in total. I hope you enjoy it! Here are some pictures of the binding process. Unfortunately, I couldn’t finish it (for obvious reasons), but managed to get about halfway through. I can’t wait to complete the binding when I get back to school. Jamie Thorogood 22nd June 2020 The Pioneer & The Savage Table of Contents Prologue ........................................................................................ 1 Part 1 New Britton ........................................................................ 1 The Mysterious Boy ........................................................................................................... 2 A Visitor ........................................................................................................................... 7 Rhaine ........................................................................................................................... -

È¿ˆå…‹Å°”·ưŅ‹É€Š ƌ曲 ĸ²È¡Œ

è¿ˆå…‹å°”Â·æ° å…‹é€Š æŒ æ›² 串行 Is It Scary Why Loving You (Michael Jackson song) Mind Is the Magic Dangerous Dangerous Dirty Diana The Way You Make Me Feel A Place with No Name 一個沒有åå — 的地方 All the Things You Are Much Too Soon Best of Joy (I Can't Make It) Another Day Working Day and Night On the Line Behind the Mask Keep the Faith Farewell My Summer Love Can You Feel It Destiny Just Good Friends She Drives Me Wild What More Can I Give Cheater Childhood Baby Be Mine Why You Wanna Trip on Me Give In to Me Earth Song Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough Give In to Me I Wanna Be Where You Are With a Child's Heart Music and Me The Way You Make Me Feel Billie Jean Rockin' Robin Smile Girl Don't Take Your Love from Me In Our Small Way Wings of My Love æ„›æƒ…å¾žæœªå¦‚æ¤ ç¾Žå¥½ Got to Be There Blue Gangsta Do You Know Where Your Children Are Chicago (Michael Jackson song) èŠå Š å“¥ (éº¥å¯ Â·å‚‘å…‹æ£®æŒ æ›²) Slave to the Rhythm (Michael Jackson song) Don't Stop 'til You Get Enough Rock with You Off the Wall Rock with You Money Morphine Breaking News Be Not Always Bad Billie Jean Beat It Shake Your Body Earth Song Dirty Diana Price of Fame The Lady in My Life Carousel Someone in the Dark Love Never Felt So Good You Are My Life You Are My Life Invincible Nobody's Business Todo Mi Amor Eres Tu Get on the Floor I Can't Help It She's Out of My Life We’ve Had Enough Jam We Are the World Heal the World Bad (éº¥å¯ Â·å‚‘å…‹æ£®æŒ æ›²) You Rock My World 天旋地轉 Stranger in Moscow Stranger in Moscow For All Time Scream Got The Hots We've Got a Good Thing Going MJ: The Musical Shout Ghosts Maria (You Were the Only One) å¥³å© å±¬æ–¼æˆ‘ Heal the World You Are Not Alone You Are Not Alone Can't Let Her Get Away Burn This Disco Out 2 Bad P.Y.T. -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Michael Jackson Dance Video Free Download

Michael jackson dance video free download Continue It is undoubtedly that Michael Jackson is the king of pop music. This title is synonymous with the musical feat that Jackson brought to the world. Songs such as Beat It, Smooth Criminal and Billie Jean redefined the music genre for decades to come. Jackson's well-designed music videos and infamous dance moves such as The Moonwalk have gained a loyal fan base and resonated with the rest of the world. In June 2009, as Jackson was preparing for his tour, he met his passing, and fans around the world expressed their grief. To this day, his songs continue to prove that he is far from oblivion, his unique style, voice and dance moves prove again and again. It is important to preserve your heritage and step one of this downloading his music videos. Now just follow the steps to upload a video of Michael Jackson to your computer. Fortunately, Michael Jackson has an official YouTube channel in which you can watch and listen to all his big time hits. In this case, Video Keeper Lite is your best bet to download them. It can download countless YouTube videos without any hassle. In addition, it offers video download speeds that have no analogues in any other video download software. Video Keeper Lite boasts multi-dark technology that uses all the bandwidth of your network. Finally, you can also save the entire YouTube playlist, which consists of Michael Jackson songs or music videos without breaking a sweat. Step 1 Install the software you can see the download button above. -

Bowdoin Vol85, No3 Spring 2014.Indd

Bowdoinspring 2014 Vol. 85 no. 3 M a g a z i n e contents BowdoinM a g a z i n e From the Editor Volume 85, Number 3 12 Spring 2014 Magazine Staff Editor Matthew J. O’Donnell Batter Up! Managing Editor My eleven-year-old daughter is playing softball. Late in a recent game, a new pitcher Scott C. Schaiberger ’95 took the mound and started windmilling Scud missiles from forty feet—bright Executive Editor yellow blurs into the backstop, the umpire’s collarbone, behind the batter, and every Alison M. Bennie few deliveries, suddenly straight into the catcher’s mitt. The on-deck batter froze Design in the circle and broke down in tears. The game was delayed while coaches and Charles Pollock teammates intervened. Then, I heard a familiar voice say, “Do you want me to go? Mike Lamare PL Design – Portland, Maine I’ll go.” My usually reserved daughter hurried to plate, tapped it hard with her bat, and dug in. I’ve never been more proud of her. Contributors James Caton At Commencement a few days later, the Rev. Bobby Ives ’69 delivered the Douglas Cook invocation for the Class of 2014, urging those members to “be not afraid” as they John R. Cross ’76 made their ways into the wider world. “Be not afraid to fail, and to make mistakes,” Rebecca Goldfine Melody Hahm ’13 he compelled them, “but to see all failing as an opportunity to learn and to change, features Scott W. Hood to improve and to grow.” The day before, Dean of Student Affairs Tim Foster greeted 6 Megan Morouse the Baccalaureate audience with a litany of Bowdoin graduates who have had Abby McBride the courage and resolve to achieve firsts—in science and medicine, technology 6 Bring on the Science Walt Wuthman ’14 and business, in scholarship, exploration, athletics, and in the armed forces. -

Table of Contents

29488 Addendum 09:Layout 1 6/11/09 5:00 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sheet Music..................................................................................................2 E-Z Play® Today Series ...............................................................................49 Fake Books..................................................................................................3 Instrumental ..............................................................................................50 Paperback Songs .................................................................................4 Accordion..........................................................................................56 Piano Chord Songbooks.......................................................................4 Big Band Play-Along...........................................................................52 Lyric Collections...................................................................................4 Brass .................................................................................................56 Personality Folios.........................................................................................5 Flute ..................................................................................................55 Songwriter Collections ...............................................................................18 Instrumental Solos.............................................................................52 Mixed Folios ..............................................................................................25 -

Billboard Magazine

Pop's princess takes country's newbie under her wing as part of this season's live music mash -up, May 31, 2014 1billboard.com a girl -powered punch completewith talk of, yep, who gets to wear the transparent skirt So 99U 8.99C,, UK £5.50 SAMSUNG THE NEXT BIG THING IN MUSIC 200+ Ad Free* Customized MINI I LK Stations Radio For You Powered by: Q SLACKER With more than 200 stations and a catalog of over 13 million songs, listen to your favorite songs with no interruption from ads. GET IT ON 0)*.Google play *For a limited time 2014 Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC. Samsung and Milk Music are both trademarks of Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. Appearance of device may vary. Device screen imagessimulated. Other company names, product names and marks mentioned herein are the property of their respective owners and may be trademarks or registered trademarks. Contents ON THE COVER Katy Perry and Kacey Musgraves photographed by Lauren Dukoff on April 17 at Sony Pictures in Culver City. For an exclusive interview and behind-the-scenes video, go to Billboard.com or Billboard.com/ipad. THIS WEEK Special Double Issue Volume 126 / No. 18 TO OUR READERS Billboard will publish its next issue on June 7. Please check Billboard.biz for 24-7 business coverage. Kesha photographed by Austin Hargrave on May 18 at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. FEATURES TOPLINE MUSIC 30 Kacey Musgraves and Katy 5 Can anything stop the rise of 47 Robyn and Royksopp, Perry What’s expected when Spotify? (Yes, actually.) Christina Perri, Deniro Farrar 16 a country ingenue and a Chart Movers Latin’s 50 Reviews Coldplay, pop superstar meet up on pop trouble, Disclosure John Fullbright, Quirke 40 “ getting ready for tour? Fun and profits. -

The Differentiated Effects of Lyrical and Non-Lyrical Music on Reading Comprehension

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 9-9-2014 The differentiated effects of lyrical and non-lyrical music on reading comprehension Cameron Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Student Counseling and Personnel Services Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Cameron, "The differentiated effects of lyrical and non-lyrical music on reading comprehension" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 352. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/352 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIFFERENTIATED EFFECTS OF LYRICAL AND NON-LYRICAL MUSIC ON READING COMPREHENSION by Cameron Campbell Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Psychology College of Science and Mathematics In partial fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Masters of Arts in School Psychology at Rowan University May 7, 2014 Thesis Chair: Roberta Dihoff, Ph.D. © 2013 Cameron Campbell Miller Abstract Cameron Campbell Miller THE DIFFERENTIATED EFFECTS OF LYRICAL AND NON-LYRICAL MUSIC ON READING COMPREHENSION 2013/14 Roberta Dihoff, Ph.D. Master of Arts in School Psychology The present study seeks to observe the effect of background music on reading comprehension, specifically searching for possible differences between effects brought on by different genres (i.e. classical and rock) and the presence of lyrics. Research on task performance in the presence of background sound is mixed, in part due to the large number of possible applications.