The Middle of Nowhere: the Photographic Search for an Unknown Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

270 Songs, 17.5 Hours, 1.62 GB Page 1 of 8 Name BPM Genre Rating

Page 1 of 8 WCS 270 songs, 17.5 hours, 1.62 GB Name BPM Genre Rating Artist Album Year Freezing 76 Pop Music Mozella Belle Isle (Deluxe… 2010 Thinking Out Loud 79 Pop Ballad Ed Sheeran x 2014 I'm So Miserable 83 Country Billy Ray Cyrus Some Gave All 1992 Too Darn Hot (RAC Mix) 83 R&B Ella Fitzgerald Verve Remixed: T… 2013 Feelin' Love 83 Blues Paula Cole City of Angels OST 1998 I'm Not the Only One 83 Pop Ballad Sam Smith In the Lonely Hou… 2014 Free 84 R&B Haley Reinhart Listen Up! 2012 Stompa 84 Alt Pop Serena Ryder Harmony 2012 Treat You Better 84 Pop Music Shawn Mendes Illuminate 2016 Heartbreak Road 85 Blues Rock Colin James Hearts on Fire 2015 Shape of My Heart 85 Rock Ballad Theory of a Deadman Shape of My Hear… 2017 Gold 86 Pop Music Kiiara low kii savage - EP 2015 I'm the Only One 87 Blues Rock Melissa Etheridge Yes I Am 1993 Rude Boy 87 Pop Music Rihanna Rated R 2009 Then 88 Pop Music Anne-Marie Speak Your Mind 2017 Can't Stay Alone Tonight 88 Pop-Rock Elton John The Diving Board… 2013 Vinyl (Remix) 88 Jazz-Pop Euge Groove feat. x-t.o.p. Sax S Euge Groove 2000 Wake Up Screaming 88 Country Gary Allan Used Heart For Sale 2000 Anything's Possible 88 R&B Jonny Lang Turn Around 2006 Slow Hands 88 Pop Music Niall Horan Slow Hands - Sin… 2017 Touch Of Heaven 88 Pop-Rock Richard Marx Flesh & Bone 1997 Forever Drunk 89 R&B Miss Li Beats & Bruises 2011 Let's Get Back To Bed Boy 89 R&B Sarah Connor Green Eyed Soul 2002 I Can't Stand the Rain 89 Pop-Soul Seal Soul 2008 Happy 90 R&B Ashanti Ashanti 2002 Mood For Luv 90 R&B B.B. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

È¿ˆå…‹Å°”·ưŅ‹É€Š ƌ曲 ĸ²È¡Œ

è¿ˆå…‹å°”Â·æ° å…‹é€Š æŒ æ›² 串行 Is It Scary Why Loving You (Michael Jackson song) Mind Is the Magic Dangerous Dangerous Dirty Diana The Way You Make Me Feel A Place with No Name 一個沒有åå — 的地方 All the Things You Are Much Too Soon Best of Joy (I Can't Make It) Another Day Working Day and Night On the Line Behind the Mask Keep the Faith Farewell My Summer Love Can You Feel It Destiny Just Good Friends She Drives Me Wild What More Can I Give Cheater Childhood Baby Be Mine Why You Wanna Trip on Me Give In to Me Earth Song Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough Give In to Me I Wanna Be Where You Are With a Child's Heart Music and Me The Way You Make Me Feel Billie Jean Rockin' Robin Smile Girl Don't Take Your Love from Me In Our Small Way Wings of My Love æ„›æƒ…å¾žæœªå¦‚æ¤ ç¾Žå¥½ Got to Be There Blue Gangsta Do You Know Where Your Children Are Chicago (Michael Jackson song) èŠå Š å“¥ (éº¥å¯ Â·å‚‘å…‹æ£®æŒ æ›²) Slave to the Rhythm (Michael Jackson song) Don't Stop 'til You Get Enough Rock with You Off the Wall Rock with You Money Morphine Breaking News Be Not Always Bad Billie Jean Beat It Shake Your Body Earth Song Dirty Diana Price of Fame The Lady in My Life Carousel Someone in the Dark Love Never Felt So Good You Are My Life You Are My Life Invincible Nobody's Business Todo Mi Amor Eres Tu Get on the Floor I Can't Help It She's Out of My Life We’ve Had Enough Jam We Are the World Heal the World Bad (éº¥å¯ Â·å‚‘å…‹æ£®æŒ æ›²) You Rock My World 天旋地轉 Stranger in Moscow Stranger in Moscow For All Time Scream Got The Hots We've Got a Good Thing Going MJ: The Musical Shout Ghosts Maria (You Were the Only One) å¥³å© å±¬æ–¼æˆ‘ Heal the World You Are Not Alone You Are Not Alone Can't Let Her Get Away Burn This Disco Out 2 Bad P.Y.T. -

How to Get Home from Here

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 How to Get Home From Here Kristin Taylor Dishmon Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dishmon, Kristin Taylor, "How to Get Home From Here" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 218. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/218 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to Get Home from Here a novella Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Languages & Literature of Bard College by K. Dishmon Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 Acknowledgements Joseph O’Neill. Thank you for your belief. Who else would suggest I call a motel to find out how it got its name? From your fiction workshop up until now, the way you look at fiction has been inspiring and meaningful. I am so grateful for your time. I cannot thank you enough for your support and for your wit. -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Michael Jackson Dance Video Free Download

Michael jackson dance video free download Continue It is undoubtedly that Michael Jackson is the king of pop music. This title is synonymous with the musical feat that Jackson brought to the world. Songs such as Beat It, Smooth Criminal and Billie Jean redefined the music genre for decades to come. Jackson's well-designed music videos and infamous dance moves such as The Moonwalk have gained a loyal fan base and resonated with the rest of the world. In June 2009, as Jackson was preparing for his tour, he met his passing, and fans around the world expressed their grief. To this day, his songs continue to prove that he is far from oblivion, his unique style, voice and dance moves prove again and again. It is important to preserve your heritage and step one of this downloading his music videos. Now just follow the steps to upload a video of Michael Jackson to your computer. Fortunately, Michael Jackson has an official YouTube channel in which you can watch and listen to all his big time hits. In this case, Video Keeper Lite is your best bet to download them. It can download countless YouTube videos without any hassle. In addition, it offers video download speeds that have no analogues in any other video download software. Video Keeper Lite boasts multi-dark technology that uses all the bandwidth of your network. Finally, you can also save the entire YouTube playlist, which consists of Michael Jackson songs or music videos without breaking a sweat. Step 1 Install the software you can see the download button above. -

Bowdoin Vol85, No3 Spring 2014.Indd

Bowdoinspring 2014 Vol. 85 no. 3 M a g a z i n e contents BowdoinM a g a z i n e From the Editor Volume 85, Number 3 12 Spring 2014 Magazine Staff Editor Matthew J. O’Donnell Batter Up! Managing Editor My eleven-year-old daughter is playing softball. Late in a recent game, a new pitcher Scott C. Schaiberger ’95 took the mound and started windmilling Scud missiles from forty feet—bright Executive Editor yellow blurs into the backstop, the umpire’s collarbone, behind the batter, and every Alison M. Bennie few deliveries, suddenly straight into the catcher’s mitt. The on-deck batter froze Design in the circle and broke down in tears. The game was delayed while coaches and Charles Pollock teammates intervened. Then, I heard a familiar voice say, “Do you want me to go? Mike Lamare PL Design – Portland, Maine I’ll go.” My usually reserved daughter hurried to plate, tapped it hard with her bat, and dug in. I’ve never been more proud of her. Contributors James Caton At Commencement a few days later, the Rev. Bobby Ives ’69 delivered the Douglas Cook invocation for the Class of 2014, urging those members to “be not afraid” as they John R. Cross ’76 made their ways into the wider world. “Be not afraid to fail, and to make mistakes,” Rebecca Goldfine Melody Hahm ’13 he compelled them, “but to see all failing as an opportunity to learn and to change, features Scott W. Hood to improve and to grow.” The day before, Dean of Student Affairs Tim Foster greeted 6 Megan Morouse the Baccalaureate audience with a litany of Bowdoin graduates who have had Abby McBride the courage and resolve to achieve firsts—in science and medicine, technology 6 Bring on the Science Walt Wuthman ’14 and business, in scholarship, exploration, athletics, and in the armed forces. -

Billboard Magazine

Pop's princess takes country's newbie under her wing as part of this season's live music mash -up, May 31, 2014 1billboard.com a girl -powered punch completewith talk of, yep, who gets to wear the transparent skirt So 99U 8.99C,, UK £5.50 SAMSUNG THE NEXT BIG THING IN MUSIC 200+ Ad Free* Customized MINI I LK Stations Radio For You Powered by: Q SLACKER With more than 200 stations and a catalog of over 13 million songs, listen to your favorite songs with no interruption from ads. GET IT ON 0)*.Google play *For a limited time 2014 Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC. Samsung and Milk Music are both trademarks of Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. Appearance of device may vary. Device screen imagessimulated. Other company names, product names and marks mentioned herein are the property of their respective owners and may be trademarks or registered trademarks. Contents ON THE COVER Katy Perry and Kacey Musgraves photographed by Lauren Dukoff on April 17 at Sony Pictures in Culver City. For an exclusive interview and behind-the-scenes video, go to Billboard.com or Billboard.com/ipad. THIS WEEK Special Double Issue Volume 126 / No. 18 TO OUR READERS Billboard will publish its next issue on June 7. Please check Billboard.biz for 24-7 business coverage. Kesha photographed by Austin Hargrave on May 18 at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. FEATURES TOPLINE MUSIC 30 Kacey Musgraves and Katy 5 Can anything stop the rise of 47 Robyn and Royksopp, Perry What’s expected when Spotify? (Yes, actually.) Christina Perri, Deniro Farrar 16 a country ingenue and a Chart Movers Latin’s 50 Reviews Coldplay, pop superstar meet up on pop trouble, Disclosure John Fullbright, Quirke 40 “ getting ready for tour? Fun and profits. -

New Training Songs Jess Glynne Song Title Code Sabay Natin 19854 Popularized By: Daniel Padilla

platinumkaraoke.ph New Songs 1 May 2016 HDD ! Randy Diamante 17761 Morissette Love 17740 New Songs Goodrum Song Title Code Disaster 17699 Jojo Mananatili 17760 Marlo Mortel & Popularized By: Janella Salvador A Better Man 17730 Toni Braxton Ditanto Agsina 17700 Ilocano Song Minamahal Pa Rin Ako 17755 Daryl Ong A Certain Smile 17725 Introvoys Dito Sa Puso Ko 17701 Josh Santana & Money 17739 Lawson Nikki Gil Morning Noon And A Million Love Songs 17709 Take That Do The Walls Come Down 17702 Carly Simon Night Time 17711 Jane Olivor A Place With No Name 17684 Michael Don't Know Why 17703 Norah Jones No 17742 Meghan Trainor Jackson A Teenagers Romance 17685 Ricky Nelson Drive You Crazy 17704 Pitbull ft Jason Only You 17707 After Image Derulo and A Woman Needs Love 17686 Ray Parker Jr & Empty Space 17771 JuicyThe Story J So Otso Pa 17750 Grin Raydio Far Department Addams Groove 17741 Mc Hammer Endless Summer Nights 17706 Richard Marx Out Of Touch 17720 Hall & Oates Aint Looking For Love 17774 Loverboy Explode 17747 Patrick Stump Patay Na Si Uto 17729 Nyoy Volante Alive 17738 Krewella Finna Get Loose 17749 Puff Daddy and Puedepende 17770 Edray Teodoro The Family (ft Pharrell All That's Left 17688 Christian Flight 17713 Lifehouse Rest Your Love 17769 The Vamps Bautista All This Time 17689 Side A ft Sharon Get Me Right 17714 Dashboard Running With The 17777 Against The Cuneta Confessional Wild Things Current Along Comes Mary 17690 The Association Get Me Some Of That 17715 Thomas Rett Sa Aking Pagpikit 17776 Midnight Meetings Ambon 17708 Barbie Almalbis -

Gig” “This Won’T TICKETS Be Just MONKEYSARCTICTO SEE

Gruff Rhys Pete Doherty Wolf Alice SECRET ALBUM DETAILS! Tune-Yards “I’ve been told not to tell but…” 24 MAY 2014 MAY 24 The Streets IAN BROWN IAN “This won’t Arctic be just another gig” Monkeys “It’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at...” on their biggest weekend yet and what lies beyond ***R U going to be down the front?*** Interviews with the stellar Finsbury Park line-up Miles Kane Tame Impala Royal Blood The Amazing Snakeheads TICKETS TO SEE On the town with Arctics’ THE PAST, PRESENT favourite new band ARCTIC & FUTURE OF MUSIC WIN 24 MAY 2014 | £2.50 HEADLINE US$8.50 | ES€3.90 | CN$6.99 MONKEYS BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME14021105.pgs 16.05.2014 12:29 BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME14018164.pgs 25.04.2014 13:55 ESSENTIAL TRACKS NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 24 MAY 2014 4 SOUNDING OFF 8 THE WEEK THIS WEEK 16 IN THE STUDIO Pulled Apart By Horses 17 ANATOMY OF AN ALBUM The Streets – WE ASK… ‘A Grand Don’t Come For Free’ NEW 19 SOUNDTRACK OF MY LIFE Anton Newcombe, The Brian Jonestown Massacre BANDS TO DISCOVER 24 REVIEWS 40 NME GUIDE → THE BAND LIST 65 THIS WEEK IN… Alice Cooper 29 Lykke Li 6, 37 Anna Calvi 7 Lyves 21 66 THINK TANK The Amazing Mac Miller 6 Snakeheads 52 Manic Street Arctic Monkeys 44 Preachers 7 HOW’s PETE SPENDING Art Trip And The Michael Jackson 28 ▼FEATURES Static Sound 21 Miles Kane 50 Benjamin Booker 20 Mona & Maria 21 HIS TIME BEFORE THE Blaenavon 32 Morrissey 6 Bo Ningen 33 Mythhs 22 The Brian Jonestown Nick Cave 7 Massacre 19 Nihilismus 21 LIBS’ COMEBACK? Chance The Rapper 7 Oliver Wilde 37 Charli XCX 32 Owen Pallett 27 He’s putting together a solo Chelsea Wolfe 21 Palm Honey 22 8 Cheerleader 7 Peace 32 record in Hamburg Clap Your Hands Phoria 22 Say Yeah 7 Poliça 6 The Coral 15 Pulled Apart By 3 Courtly Love 22 Horses 16 IS THERE FINALLY Courtney Barnett 31 Ratking 33 Arctic Monkeys Courtney Love 36 Rhodes 6 Barry Nicolson gets the skinny Cymbals Eat Guitars 7 Royal Blood 51 A GOOD Darlia 40 Röyksopp & Robyn 27 on their upcoming Finsbury Echo & The San Mei 22 Park shows. -

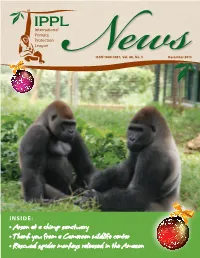

• Arson at a Chimp Sanctuary • Thank You from a Cameroon Wildlife Center • Rescued Spider Monkeys Released in the Amazon IPPL at 40! a Note from Shirley 1973-2013

NewsISSN-1040-3027, Vol. 40, No. 3 December 2013 InsidE: • Arson at a chimp sanctuary • Thank you from a Cameroon wildlife center • Rescued spider monkeys released in the Amazon IPPL at 40! A Note from Shirley 1973-2013 IPPL: Who We Are IPPL is an international grassroots wildlife protection organization. It was founded in 1973 by Dr. Shirley McGreal. Our mission is to promote the conservation and protection of all nonhuman primates, great and small. IPPL has been operating a sanctuary in Summerville, South Carolina, since 1977. There, 37 gibbons (the smallest of the apes) live in happy retirement. IPPL also helps support a number of other wildlife groups and primate rescue centers in countries where monkeys and apes are native. IPPL News is published thrice-yearly. Me with Hardy’s horse Aachje. About the Cover Dear IPPL Friend, Batek (left) and Benito (right) are two All of us at IPPL extend to all our friends worldwide our good wishes for a happy of the gorillas residing at the Limbe holiday season. Wildlife Centre in Cameroon. This past On the good news side, we started the year with 33 gibbons and ended up with June, IPPL sent a special appeal to our 37, thanks to the arrival of four gibbons left homeless after the Silver Springs tourist supporters, asking for donations to help attraction in Florida closed its animal exhibits. The park staff was busy arranging this important primate sanctuary. This new homes for Kodiak bears, crocodiles, and more—around 250 animals in all! fundraiser was a great success, and as Among the Silver Springs residents were two elderly gibbons, Gary and Glenda, a result IPPL has been able to send over and their two youngsters, Thai and Kendra.