A Jewish Prayer Book in the Modern Age Were Ignored Merely Because the Solution of Reform Was Found Inadequate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

'Jhe Umertcan 'Jitle Ussocia.Tion, 2 TITLE NEWS

• SEPTEMBER, 1926 CONTENTS THE MONTHLY LETTER ______________________________________ Page 2 EDITOR'S PAGE ------------------------------------------------------ " 3 "LIABILITY OF ABSTRACTERS" By V. E. Phillips ___________________________________________ --------- ------- ___ " 4 An interesting presentation of this subject, and something that will be very valuable to have. REPORTS OF STATE MEETINGS Oregon ---------------------- -------------------- --- -- ----- --------· " 10 Wisconsin ---------------·------------·----------------------------- " 10 Montana ------------------------------------------------------------ " 11 South Dakota ----------·----------------------------------------- " 11 North Dakota -------------------------------------- _____________ " 12 Ohio ----------·----------------------------------------------------· " 13 LAW QUESTIONS AND THE C 0 U R T S ANSWERS ·----------· ·-------------- ------------- ---------------- " 14 The Monthly Review. SUSTAINING FUND MEMBERSHIP ROLL- 1926 -------·---------------------- ---- ------ --- ---- --------------- ---- " 17 ABSTRACTS OF LAND TITLES ---· ----------------- ------ - " 20 Another installment on their preparation. MISCELLANEOUS INDEX ------------------------------------ " 22 News of the title world. ANNOUNCEMENTS OF STATE MEETINGS Kansas Title Association ------------------------------- " 21 Michigan Title Association ------------------------------ " 21 Nebraska Ttitle Association -------------------·-·-·-·-· " 24 A PUBLICATION ISSUED MONTHLY BY 'Jhe Umertcan 'Jitle Ussocia.tion, -

The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland—An Outline

The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland ♦ 1 The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland—an Outline Michał Galas Jagiellonian University In the historiography of Judaism in the Polish lands the influence of Reform Judaism is often overlooked. he opinion is frequently cited that the Polish Jews were tied to tradition and did not accept ideas of religious reform coming from the West. his paper fills the gap in historiography by giving some examples of activities of progressive communities and their leaders. It focuses mainly on eminent rabbis and preachers such as Abraham Goldschmidt, Markus Jastrow, and Izaak Cylkow. Supporters of progressive Judaism in Poland did not have as strong a position as representatives of the Reform or Conservative Judaism in Germany or the United States. Religious reforms introduced by them were for a number of reasons moderate or limited. However, one cannot ignore this move- ment in the history of Judaism in Poland, since that trend was significant for the history of Jews in Poland and Polish-Jewish relations. In the historiography of Judaism in the Polish lands, the history of the influ- ence of Reform Judaism is often overlooked. he opinion is frequently cited that the Polish Jews were tied to tradition and did not accept ideas of religious reform coming from the West. his opinion is perhaps correct in terms of the number of “progressive” Jews, often so-called proponents of reform, on Polish soil, in comparison to the total number of Polish Jews. However, the influence of “progressives” went much further and deeper, in both the Jewish and Polish community. -

We All Know, the Emancipation Was a Great Turning Point in the History Of

PROGRESSIVE LITURGIES OF GERMANY AND AMERICA 585 p- John D. Rayner Introduction As we all know, the Emancipation was a great turning point in the history of Judaism, although ‘point' is hardly the right word, since it was a long-drawn- out process extending from the eighteenth century into the twentieth. Nevertheless the initial impact of it was often felt by a single generation, and in Germany by the generation of those born during the Napoleonic era. As we all know; too, the initial impact was for many of the newly emancipated German Jews a negative one so far as their Jewish religious life was concerned because the revolutionary educational, linguistic, cultural and social changes they experienced caused them to feel uncomfortable in the old- style synagogues. And as we all know as well, it is to this problem, of the alienation of emancipated Jewry from the traditional synagogue that the Reformers first and foremost addressed themselves. They believed that if only the synagogue services could be made more attractive, that would halt and perhaps reverse w the drift. 0 . _ {:1 j N In retrospect we can see that they were only partly right. There are other 8E}; factors besides the nature of synagogue worship which determine or influence the extent to which individuals will affirm their Jewish identity \ :8 " and adhere to their Jewish faith, and subsequent generations of Reformers 13E came to recognise that and to address themselves to these other issues also. (3 ‘1‘: Nevertheless the nature of synagogue worship is clearly a factor, and a big one. -

The Secular Music of the Yemenite Jews As an Expression of Cultural Demarcation Between the Sexes

JASO 27/2 (1996): 113-135 THE SECULAR MUSIC OF THE YEMENITE JEWS AS AN EXPRESSION OF CULTURAL DEMARCATION BETWEEN THE SEXES MARILYN HERMAN JEWISH men and women in Yemen are portrayed in the sociological and anthropo logical literature as having lived in separate conceptual and spatial worlds. As a result, two very separate bodies of song existed, one pertaining to men and the other to women. In this paper, I show how the culturally defined demarcation be tween the sexes is reflected and epitomized in the music of the Jews who lived in Yemen. i The key to this separation lies in the fact that women were banned from the synagogue altogether. This exclusion is not prescribed by Jewish law, and there is no precedent for it in the Bible or other Jewish literature or communities. The reason given for women being banned from the synagogue in Yemen was the fear that they might be menstruating. The condition of menstruation is, in Jewish law, This paper is based on my MA thesis (Herman 1985), which was written under the supervision and with the moral and academic support of Dr P. T. W. Baxter of Manchester University. My brother Geoffrey Herman willingly and painstakingly translated Hebrew articles into English for my benefit while I was writing this thesis. I. The period mainly referred to is the fifty years or so preceding 'Operation Magic Carpet', a series of airlifts between 1949 and 1950 in which the majority of Yemenite Jews were taken to Israel. 114 Marilyn Herman seen as ritually impure. -

Podcast Transcript Cantor Louise Treitman

Open My Heart: Living Jewish Prayer with Rabbi Jonathan Slater Cantor Louise Treitman. JONATHAN: Shalom. This is Rabbi Jonathan Slater, and welcome to “Open My Heart: Living Jewish Prayer”, a Prayer Project Podcast of the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. Together, we will investigate how personal prayer, in its many forms, is an important part of Jewish spirituality. Each Monday and Friday, we will offer a different practice, led by a different person, all praying from the heart. Today, we're blessed to have with us Cantor Louise Treitman, who is a student and a friend. Hey Louise. Really happy to have you here. Tell us a little bit about yourself. LOUISE: Thank you, Jonathan. It's so great to be with you today. I'm a cantor and I've served in the Boston area since the 1980s. I'm blessed to be Cantor Emerita of Temple Beth David in Westwood, Massachusetts, and I also – at Hebrew college in Newton, Massachusetts -- I teach rabbinical and cantorial and education students. It's a pluralistic seminary here. In recent years. I've been serving a World Union for Progressive Judaism congregation in Italy. First, I was in Florence and then most recently in Rome. This is for the High Holidays, and currently via Zoom for monthly Shabbatot. I've been involved with the Institute for Jewish Spirituality, IJS, almost since its beginning, and was thrilled to finally be in the first Clergy Cohort. I've led some of the regular Daily Meditations, and I've also been listening to these personal prayer practice podcasts since they started. -

Volume 124, Issue 6 (The Sentinel, 1911

-- jr .1 V £L Aovemoer 6, 1941 .111 ,. Ili. 4A In an impressive double ceremony, two sis- In honor of the betrothal of Miss Marian ters were united in matrimony, Nettie and Loeffler, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. M. Loeffler Josephine Silver, daughters of Mr. and Mrs. to Mr. Henry Pollak, son of Mr. and Mrs. Emil H. W. Silver of 3520 Lake Shore Drive, were Pollak, a dinner party was tendered the young married at the Belmont Hotel on Sunday, Octo- couple by Mrs. Emil Pollak, in which members R. AND MRS. Leo Goldstein of 1540 ber 26. Miss Nettie Silver was wed to Mr. of both families joined in the celebration. Lake Shore Drive left last week for Clyde Korman, son of Mr. and Mrs. Korman Among those present on this special occasion New York City. Mr. Goldstein has al- of the Melrose Hotel, and Josephine to Mr. were Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Berlin, Mrs. Birdie Goldstein is ready returned to this city. Mrs. Barney Joseph of the Parkway Hotel. Rabbi Levy, Mrs. Joseph Reich, Mr. and Mrs. Rudolph remaining in New York for another week. Solomon Goldman officiated. Following the Sabbath, Mr. and Mrs. Harry Glickauf, Mr. Mr. and Mrs. Egmont H. Frankel of Toronto, double nuptials, a breakfast was served at the and Mrs. L. Hecht, Mr. and Mrs. M. Loeffler, Canada, who were the guests of their mother, Belmont Hotel, and the two couples left on a Mr. and Mrs. Al Horn, Mr. Jerome Sabbath, Mrs. Abraham Hartman of the Chicago Beach double honeymoon. On Sunday, November 2, Mr. -

The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook'

"We Are Bound to Tradition Yet Part of That Tradition Is Change": The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook' Ilana Harlow Indiana University The traditional Jewish liturgy in its diverse manifestations is an imposing artistic structure. But unlike a painting or a symphony it is not the work of one artist or even the product of one period. It is more like a medieval cathedral, in the construction of which many generations had a share and in the ultimate completion of which the traces of diverse tastes and styles may be detected. (Petuchowski 1985:312) This essay explores the dynamics between tradition and innovation, authority and authenticity through a study of a recently edited Jewish prayerbook-a contemporary development in a tradition which can be traced over a one-thousand year period. The many editions of the Jewish prayerbook, or siddur, that have been compiled over the centuries chronicle the contributions specific individuals and communities made to the tradition-informed by the particular fashions and events of their times as well as by extant traditions. The process is well-captured in liturgist Jakob Petuchowski's 'cathedral simile' above-an image which could be applied equally well to many traditions but is most evident in written ones. An examination of a continuously emergent written tradition, such as the siddur, can help highlight kindred processes involved in the non-documented development of oral and behavioral traditions. Presented below are the editorial decisions of a contemporary prayerbook editor, Rabbi Jules Harlow, as a case study of the kinds of issues involved when individuals assume responsibility for the ongoing conserva- tion and construction of traditions for their communities. -

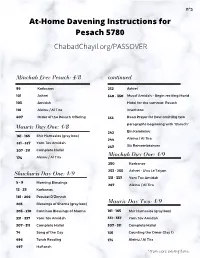

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

The Role of Hebrew Letters in Making the Divine Visible

"VTSFDIUMJDIFO (SàOEFOTUFIU EJFTF"CCJMEVOH OJDIUJN0QFO "DDFTT[VS 7FSGàHVOH The Role of Hebrew Letters in Making the Divine Visible KATRIN KOGMAN-APPEL hen Jewish figural book art began to develop in central WEurope around the middle of the thirteenth century, the patrons and artists of Hebrew liturgical books easily opened up to the tastes, fashions, and conventions of Latin illu- minated manuscripts and other forms of Christian art. Jewish book designers dealt with the visual culture they encountered in the environment in which they lived with a complex process of transmis- sion, adaptation, and translation. Among the wealth of Christian visual themes, however, there was one that the Jews could not integrate into their religious culture: they were not prepared to create anthropomorphic representations of God. This stand does not imply that Jewish imagery never met the challenge involved in representing the Divine. Among the most lavish medieval Hebrew manu- scripts is a group of prayer books that contain the liturgical hymns that were commonly part of central European prayer rites. Many of these hymns address God by means of lavish golden initial words that refer to the Divine. These initials were integrated into the overall imagery of decorated initial panels, their frames, and entire page layouts in manifold ways to be analyzed in what follows. Jewish artists and patrons developed interesting strategies to cope with the need to avoid anthropomorphism and still to give way to visually powerful manifestations of the divine presence. Among the standard themes in medieval Ashkenazi illuminated Hebrew prayer books (mahzorim)1 we find images of Moses receiving the tablets of the Law on Mount Sinai (Exodus 31:18, 34), commemorated during the holiday of Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks (fig. -

Geshem’ by Cantor Moshe Haschel

The Outpouring for ‘Geshem’ by Cantor Moshe Haschel The Mishna (Rosh Hashanah, chapter 1 mishna 2) tells us that on Sukkot the world is judged for rain. The Talmud (Taanit 7a) says in the name of Rav Yosef that the world’s dependence on rain for its sustenance is so total that rainfall is compared to the revival of the dead. This is the reason says Rav Yosef, why the Rabbis put the phrase – ‘ Mashiv Haruach uMorid Hageshem’ – ‘He makes the wind to blow and the rain to fall’ in the second blessing of the Amida which speaks about Divine Might and concludes with ‘Blessed are You, Lord, who revives the dead’. The Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 16a) brings Rabbi Yehuda’s view that the world is judged on all aspects already on Rosh Hashanah but the final judgment is sealed for each feature only in its specific time; for grain on Pesach, for fruits of trees on Shavuot and for rain on Sukkot. Rabbi Yehoshua Ibn Shuaib (13th century Spain) in his work ‘Derashot al haTorah’ (derasha for Shemini Atzeret) explains this notion in connection with rain that the amount of rain that will fall during the coming year is in fact determined already on Rosh Hashanah. However, on Sukkot it is decided where i.e. on which parts of the world it would fall, and how i.e. whether it would be beneficial to the world or otherwise. This idea is reflected in the Liturgical poem ‘Af Beri’ by Rabbi Eleazar haKalir recited at the Shemini Atzeret Mussaf repetition. -

Yom Kippur Additional Service

v¨J¨s£j jUr© rIz§j©n MACHZOR RUACH CHADASHAH Services for the Days of Awe ohrUP¦ ¦ F©v oIh§k ;¨xUn YOM KIPPUR ADDITIONAL SERVICE London 2003 - 5763 /o¤f§C§r¦e§C i¥T¤t v¨J¨s£j jU© r§ «u Js¨ ¨j c¥k o¤f¨k h¦T©,¨b§u ‘I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you.’ (Ezekiel 36:26) This large print publication is extracted from Machzor Ruach Chadashah EDITORS Rabbi Dr Andrew Goldstein Rabbi Dr Charles H Middleburgh Editorial Consultants Professor Eric L Friedland Rabbi John Rayner Technical Editor Ann Kirk Origination Student Rabbi Paul Freedman assisted by Louise Freedman ©Union of Liberal & Progressive Synagogues, 2003 The Montagu Centre, 21 Maple Street, London W1T 4BE Printed by JJ Copyprint, London Yom Kippur Additional Service A REFLECTION BEFORE THE ADDITIONAL SERVICE Our ancestors acclaimed the God Whose handiwork they read In the mysterious heavens above, And in the varied scene of earth below, In the orderly march of days and nights, Of seasons and years, And in the chequered fate of humankind. Night reveals the limitless caverns of space, Hidden by the light of day, And unfolds horizonless vistas Far beyond imagination's ken. The mind is staggered, Yet soon regains its poise, And peering through the boundless dark, Orients itself anew by the light of distant suns Shrunk to glittering sparks. The soul is faint, yet soon revives, And learns to spell once more the name of God Across the newly-visioned firmament. Lift your eyes, look up; who made these stars? God is the oneness That spans the fathomless deeps of space And the measureless eons of time, Binding them together in deed, as we do in thought.