Mare Island Regional Park Task Force Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION

CALIFORNIA HISTORIC MILITARY BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES INVENTORY VOLUME II: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIC RESOURCES OF THE MILITARY IN CALIFORNIA, 1769-1989 by Stephen D. Mikesell Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Prepared by: JRP JRP HISTORICAL CONSULTING SERVICES Davis, California 95616 March 2000 California llistoric Military Buildings and Stnictures Inventory, Volume II CONTENTS CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... i FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. iv PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1-1 2.0 COLONIAL ERA (1769-1846) .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Spanish-Mexican Era Buildings Owned by the Military ............................................... 2-8 2.2 Conclusions .................................................................................................................. -

San Pablo Bay and Marin Islands National Wildlife Refuges - Refuges in the North Bay by Bryan Winton

San Pablo Bay NWR Tideline Newsletter Archives San Pablo Bay and Marin Islands National Wildlife Refuges - Refuges in the North Bay by Bryan Winton Editor’s Note: In March 2003, the National Wildlife Refuge System will be celebrating its 100th anniversary. This system is the world’s most unique network of lands and waters set aside specifically for the conservation of fish, wildlife and plants. President Theodore Roosevelt established the first refuge, 3- acre Pelican Island Bird Reservation in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, in 1903. Roosevelt went on to create 55 more refuges before he left office in 1909; today the refuge system encompasses more than 535 units spread over 94 million acres. Leading up to 2003, the Tideline will feature each national wildlife refuge in the San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Complex. This complex is made up of seven Refuges (soon to be eight) located throughout the San Francisco Bay Area and headquartered at Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge in Fremont. We hope these articles will enhance your appreciation of the uniqueness of each refuge and the diversity of habitats and wildlife in the San Francisco Bay Area. San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge Tucked away in the northern reaches of the San Francisco Bay estuary lies a body of water and land unique to the San Francisco Bay Area. Every winter, thousands of canvasbacks - one of North America’s largest and fastest flying ducks, will descend into San Pablo Bay and the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge. This refuge not only boasts the largest wintering population of canvasbacks on the west coast, it protects the largest remaining contiguous patch of pickleweed-dominated tidal marsh found in the northern San Francisco Bay - habitat critical to Aerial view of San Pablo Bay NWR the survival of the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse. -

1 Appendix U. S. Army Corps of Engineers Maintenance

APPENDIX U. S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS MAINTENANCE DREDGING PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS SAN FRANCISCO BAY-DELTA, CA 7/21/15 PROJECT NAME: OAKLAND HARBOR, CA OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE PROJECT LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION Oakland Harbor is a high-use, deep-draft harbor located in Alameda County, California. The Port of Oakland is the major container facility in San Francisco Bay and is a National Strategic Port. The project was recently deepened from -45’ to 50-feet’ It is the third largest container port on the West coast and the fifth largest in the nation. The project includes annual maintenance dredging the Inner and Outer Harbors to a depth of -50 feet MLLW and provides for inspection and maintenance of parallel rubble-mound jetties that form the entrance to Oakland Inner Harbor, monitoring the Sonoma Baylands Wetland Demonstration Site, and for payment to Alameda County for Operations and Maintenance (O&M) of the Fruitvale Avenue Railroad Bridge. AUTHORIZATION: River and Harbor Acts of 1910, 1917, 1922, 1928, 1930, 1945, and 1962, Water Resource Development Acts of 1986 and 1999 FISCAL YEAR 2013 ACTUAL: $20,903,212 FISCAL YEAR 2014 ALLOCATION: $21,848,310 . CONFERENCE AMOUNT FOR FY 2015: $21,970,000 BUDGETED AMOUNT FOR FY 2016: M: $14,725,000 O: $275,000 T: $15,000,000 1/ DESCRIPTIONS OF WORK AND JUSTIFICATIONS FOR FY 2016: N: $15,000,000 - Funding will be used for annual contract maintenance dredging of the Inner and Outer Harbor Channels to 49-feet deep. Amount also includes annual operation of the Fruitvale Avenue Railroad Bridge. PROJECT NAME: REDWOOD CITY HARBOR, CA OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE PROJECT LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION Redwood City Harbor is located on San Francisco Bay in San Mateo County. -

18-1246 PC M 11-12-2020.Pdf

Communication from Public Name: Daniel Gaines Date Submitted: 11/12/2020 12:54 PM Council File No: 18-1246 Comments for Public Posting: This ordinance, if passed, would essentially ignore our housing crisis and prioritize tourists over long term tenants and the wealthy over people who desperately need housing. As someone who works in homeless services, I see firsthand how the shortage of housing is a public health issue for the folks I serve, and we know that deaths of unhoused individuals have skyrocketed in recent months. LA is in a state of emergency when it comes to housing and I implore the council to alleviate the crisis of houselessness BEFORE focusing on lodgings for tourists who all have homes to return to. It is unconscionable for our City to consider removing housing from the long-term rental market at a time when tenants are being displaced and and homelessness is increasing. If passed, this ordinance will potentially remove 14,740 homes from the long term rental market in Los Angeles. (LA Times: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-12-19/los-angeles-vacation-rentals-city-council-considers-loosening-rules) In these dire times, we are asking PLUM to please consider who really needs their protection: working Angelenos trying to stay in their homes, or the wealthiest among us trying to profit from second homes they don’t actually live in? Communication from Public Name: Stella Grey Date Submitted: 11/11/2020 11:51 PM Council File No: 18-1246 Comments for Public Posting: Dear members of the Committee, Our neighborhood known as Bird Streets already bears the brunt of party houses epidemic. -

Status of Ospreys Nesting on San Francisco Bay ANTHONY J

STATUS OF OSPREYS NESTING ON SAN FRANCISCO BAY ANTHONY J. BRAKE, 1201 Brickyard Way, Richmond, California 94801; [email protected] HARVEY A. WILSON, 1113 Otis Drive, Alameda, California 94501; [email protected] ROBIN LEONG, 336 Benson Avenue, Vallejo, California 94590 ALLEN M. FISH, Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, Building 1064, Fort Cronkhite, Sausalito, California 94965 ABSTRACT: Historical records from the early 1900s, as well as surveys updated in the late 1980s and more recent information from local breeding bird atlases, in- dicate that Ospreys rarely nested on San Francisco Bay prior to 2005. In 2013, we surveyed nesting Ospreys baywide and located 26 nesting pairs, 17 of which were successful and fledged 44 young. We also report on findings from previous annual nest surveys of a portion of San Francisco Bay beginning in 1999. These results demonstrate a greater breeding abundance than has previously been recognized. The density of Osprey nests is highest near the north end of San Francisco Bay, but nesting also appears to be expanding southward. Nearly all of the nests observed were built on artificial structures, some of which were inappropriate and required nests to be removed. Over half of unsuccessful pairs experienced significant human disturbance. We recommend that conservation efforts focus on reducing this ratio, and to help do so, we urge erecting nest platforms as part of efforts to deter nesting when it conflicts with human activity. The Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) is a diurnal, piscivorous raptor that breeds or winters in a variety of habitats on all continents except Antarctica. Upon reaching maturity, the birds typically return close to their natal site to breed. -

Coast Guard, DHS § 117.173

Coast Guard, DHS § 117.173 § 117.161 Honker Cut. phone number to schedule drawspan operation. The draw of the San Joaquin County (b) The draw of the Northwestern Pa- (Eightmile Road) bridge, mile 0.3 be- cific railroad bridge, mile 10.6 at Braz- tween Empire Tract and King Island at os, shall be maintained in the fully Stockton, shall open on signal if at open position, except for the crossing least 12 hours notice is given to the of trains or for maintenance. When the San Joaquin County Department of draw is closed and visibility at the Public Works at Stockton. drawtender’s station is less than one mile, up or down the channel, the § 117.163 Islais Creek (Channel). drawtender shall sound two prolonged (a) The draw of the Illinois Street blasts every minute. When the draw is drawbridge, mile 0.3 at San Francisco, opened, the drawtender shall sound shall open on signal if at least 72 hours three short blasts. advance notice is given to the Port of [CGD 82–025, 49 FR 17452, Apr. 24, 1984, as San Francisco. amended by CGD 12–85–02, 50 FR 20758, May (b) The draw of the 3rd Street draw- 20, 1985; USCG–1999–5832, 64 FR 34712, June 29, bridge, mile 0.4 at San Francisco, shall 1999; CGD11–03–006, 69 FR 21958, Apr. 23, 2004; open on signal if at least 72 hours ad- CGD 11–05–025, 70 FR 20467, Apr. 20, 2005] vance notice is given to the San Fran- cisco Department of Public Works. -

Directions to the USGS San Francisco Bay Estuary Field Station 505 Azuar Drive, Vallejo, CA 94592

Directions to the USGS San Francisco Bay Estuary Field Station 505 Azuar Drive, Vallejo, CA 94592. Note: Google maps have updated and our location is correct. Mapquest and Yahoo maps are both incorrect (too far north). Hwy 37 Mare Island Causeway USGS SFBE Field Station From Sacramento From Sacramento travel west on I-80, take the Hwy 37 exit towards San Rafael. Proceed straight ahead for several miles. Take the Mare Island exit onto Walnut St, first exit after crossing the Napa River. Proceed straight ahead. Turn right onto K St, which turns into J St. At the stop sign turn left onto Azuar Dr. Take the first right onto the long driveway of the USGS field station. Our office/conference room is located in the trailer buildings near the palm trees. From San Francisco Travel east on I-80, exit Sonoma Street (first exit after the Carquinez Bridge). Continue a few miles and turn left onto Curtola Parkway. Drive along the Vallejo waterfront and turn left onto Mare Island Causeway (the main entrance to Mare Island. Proceed straight ahead until the road ends. Turn right onto Azuar Dr., follow the railroad tracks approximately one long block, and take the first left into the long driveway of the USGS field station. Our office/conference room is located in the trailer buildings near the palm trees. From Marin Travel east on Highway 37 to Vallejo. Take the Mare Island exit (one way) on Walnut Ave. Turn right onto K St. At the stop sign turn left onto Azuar Dr. Take the first right into the long driveway of the USGS field station. -

33 CFR Ch. I (7–1–14 Edition) § 117.161

§ 117.161 33 CFR Ch. I (7–1–14 Edition) open on signal if at least 12 hours no- phone at (707) 648–4313 for drawspan op- tice is given to the San Joaquin Coun- eration. When the drawbridge operator ty Department of Public Works at is not present, mariners may contact Stockton. the City of Vallejo via the same tele- phone number to schedule drawspan § 117.161 Honker Cut. operation. The draw of the San Joaquin County (b) The draw of the Northwestern Pa- (Eightmile Road) bridge, mile 0.3 be- cific railroad bridge, mile 10.6 at Braz- tween Empire Tract and King Island at os, shall be maintained in the fully Stockton, shall open on signal if at open position, except for the crossing least 12 hours notice is given to the of trains or for maintenance. When the San Joaquin County Department of draw is closed and visibility at the Public Works at Stockton. drawtender’s station is less than one mile, up or down the channel, the § 117.163 Islais Creek (Channel). drawtender shall sound two prolonged blasts every minute. When the draw is (a) The draw of the Illinois Street opened, the drawtender shall sound drawbridge, mile 0.3 at San Francisco, three short blasts. shall open on signal if at least 72 hours advance notice is given to the Port of [CGD 82–025, 49 FR 17452, Apr. 24, 1984, as San Francisco. amended by CGD 12–85–02, 50 FR 20758, May (b) The draw of the 3rd Street draw- 20, 1985; USCG–1999–5832, 64 FR 34712, June 29, bridge, mile 0.4 at San Francisco, shall 1999; CGD11–03–006, 69 FR 21958, Apr. -

Deconstructing Mare Island Reconnaissance in the Ruins

Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom/article-pdf/2/2/55/381274/boom_2012_2_2_55.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 richard white Photographs by Jesse White Deconstructing Mare Island Reconnaissance in the ruins The detritus still he Carquinez Strait has become driveover country. Beginning around Vallejo and running roughly six miles to Suisun Bay, Grizzly Bay, and the Sacramento possesses a T River Delta, the Strait has, in the daily life of California, reduced down to the Carquinez and Benicia-Martinez bridges. Motorists are as likely to be searching for grim grandeur. their toll as looking at the land and water below. Few will exit the interstates. Why stop at Martinez, Benicia, Vallejo, Crockett, or Port Costa? They are going west to Napa or San Francisco or east to Sacramento. Like travelers’ destinations, California’s future also appears to lie elsewhere. Once, much of what moved out of Northern California came through these communities, but now the Strait seems left with only the detritus of California’s past. The detritus still possesses a grim grandeur. To the east, the Mothball Fleet— originally composed of transports and battleships that helped win World War II— cluster tightly together, toxic and rusting, in Suisun Bay. Just west of the bridges, Mare Island (really a peninsula with a slough running through it) sits across the mouth of the Napa River. The United States established a naval base and shipyard there in 1854, and the island remained central to US military efforts from the Civil Boom: A Journal of California, Vol. 2, Number 2, pps 55–69. -

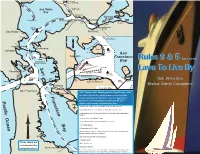

Rule 9 & 5, Laws to Live By

Petaluma River Mare Island Bridge Causeway Bridge Petaluma River Mar e I. Str Vallejo San Pablo ait Channel Bay eet Mare I. Carquinez thball Fl Bridge Mo Dillon Suisun Channel Carqu Pt. Selby inez Bay Pumphouse Davis Pt. Strait Benicia Rodeo Port nole Shoal Crockett Pi Chicago Avon "E"cho Benicia-Martinez Bridge Buoy Pt. Pinole San Rafael Martinez McNears Pt. San Pedro Bluff Pt. Southampton Shoal Channel Pt. San Pablo rait Pt. Simpton Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Richmond Raccoon StAngel I. "A"lpha Larkspur Buoy Red Pt. Knox Rock Long Wharf Pt. Blunt San Sausalito Francisco Rules 9 & 5 ....... Southampton Bay r Shoal Channel Harding e Tiburon t Rock Buoy San Alcatraz I. Deep Wate Westbound Lane Angel I. Traffic Lan Treasure I. Laws To Live By Sausalito Raccoon Strai astbound Lane Berkeley Pier E Blossom Golden Rock Buoy Gate Presidio Shoal Bridge Alcatraz I. Golden Yerba Buena I. Treasure I. Bay Gate San Francisco Bridge Bridge Bay Pt. Bonita San Francisco Bridge Harbor Safety Committee Mile Oakland Rock Central Bay San Francisco Alameda The Captain of the Port designates the following areas (in white) where deep draft commercial and public Francisco vessels routinely operate to be "narrow channels or Pacific Ocean fairways", for the purpose of enforcing RULE 9 (please refter to map for location of sites). OAK • Golden Gate Traffic Lanes and Golden Gate Precautionary Area Hunter's • Central Bay Traffic Lanes and Central Bay Precautionary Area Point • Oakland Harbor Bar Channel and Oakland Outer Harbor and Oakland Inner Harbor San Bruno Shoal • Alameda Naval Air Station Channel • So. -

Western Ships Repaired List 09/2013 1 Ship Repair Yard

WESTERN SHIPS REPAIRED LIST SHIP REPAIR YARD START END SHIP MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 5-Jul-72 15-Mar-74 ABRAHAM LINCOLN WESTERN MACARTHUR CO--SAN FRANCISCO, CA 16-Nov-69 01-Dec-69 ACHILLES 1960 MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 28-Apr-55 28-Jul-55 AGERHOLM DD-826 MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 5-Sep-57 5-Dec-57 AGERHOLM DD-826 MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 2-May-60 23-Mar-61 AGERHOLM DD-826 HUNTERS POINT NAVAL SHIPYARD--SAN 12-Sep-69 19-Dec-69 AGERHOLM DD-826 FRANCISCO, CA MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 28-Apr-58 27-Jul-58 ALAMO MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 29-Jan-54 30-Apr-54 ALFRED A CUNNINGHAM DD-752 MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 26-Aug-55 15-Nov-55 ALGOL MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 11-Sep-53 16-Nov-53 ALSTEDE MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 18-Nov-57 2-Jan-58 ALVIN C COCKRELL PACIFIC FAR EAST LINES, INC. 06-Jun-68 16-Jul-68 AMERICAN BEAR 1944 MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 1-Jan-70 7-Jan-70 ANCHORAGE MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 4-Jul-63 23-Jul-63 ANDREW JACKSON MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 5-Sep-50 5-Oct-50 ANDROMEDA MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 15-Jan-53 17-Mar-53 ANDROMEDA MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 27-Oct-53 28-Dec-53 ANDROMEDA MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 2-Jan-62 23-Apr-62 ARAPAHO MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 12-Oct-65 31-Oct-67 ARAPAHO HUNTERS POINT NAVAL SHIPYARD--SAN 14-May-62 14-Sep-62 ARCHERFISH FRANCISCO, CA MARE ISLAND NAVAL SHIPYARD--VALLEJO, CA 10-Dec-50 -

9Th Annual San Francisco Bay Osprey Days

9th San Francisco Bay Osprey Days June 25, 26 & 27, 2021 9TH ANNUAL SAN FRANCISCO BAY OSPREY DAYS Photo upper: Lee Ann Tompkins Baker, Carquinez Strait, Vallejo, CA FREE Image left: Kathleen R. Fenton * boat trips–2 hrs Even in the most trying times, nature $45 per person thrives. In our Bay, osprey still soar, Nesting Osprey have flourished dive, fish, nest, feed and fledge their in San Francisco Bay since the young. early 2000’s when the first successful nesting pair took up We hope you will join them and us, to celebrate their resilience… residence at the southernmost and ours. This year continues to be a daunting challenge for our tip of Pier 34 at the mouth of the entire team of dedicated scientists, researchers, guides, volunteers Napa River in the Mare Island and board of the Mare Island Heritage Trust. After a series of Shoreline Heritage Preserve. fires in September 2019, and after 12 years of trusted and Now, there are 56 documented protective care of the Preserve, we as a nonprofit founder, funder nests Baywide, this 2021 season. and manager of the Preserve, were dismissed by the Vallejo City HOSTED BY Manager as operating managers of the Mare Island Preserve. Still The Bay Area Osprey Coalition as confused and troubled as you are, we hold out hope for better Mare Island Heritage Trust times. Imagine, more than 8,100 fellow Preserve Users have Golden Gate Raptor Observatory signed our online petition to return the Preserve to our care. Napa Solano Audubon Society Click here to sign and share.