Journal of Academic Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanctity and Discernment of Spirits in the Early Modern Period

Angels of Light? Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow Edmonton, Alberta In cooperation with Sylvia Brown, Edmonton, Alberta Falk Eisermann, Berlin Berndt Hamm, Erlangen Johannes Heil, Heidelberg Susan C. Karant-Nunn, Tucson, Arizona Martin Kaufhold, Augsburg Erik Kwakkel, Leiden Jürgen Miethke, Heidelberg Christopher Ocker, San Anselmo and Berkeley, California Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 164 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Angels of Light? Sanctity and the Discernment of Spirits in the Early Modern Period Edited by Clare Copeland Jan Machielsen LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: “Diaboli sub figura 2 Monialium fraudulentis Sermonibus, conantur illam divertere ab incepto vivendi modo,” in Vita ser. virg. S. Maria Magdalenae de Pazzis, Florentinae ordinis B.V.M. de Monte Carmelo iconibus expressa, Abraham van Diepenbeke (Antwerp, ca. 1670). Reproduced with permission from the Bibliotheca Carmelitana, Rome. Library of Congress Control Number: 2012952309 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1573-4188 ISBN 978-90-04-23369-0 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-23370-6 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Familytree.Jennifer M. Collins.Pdf

/anuel Bryennios *heodore /etochites 5regory Pala)as 1315 131+ 131+ 9ilos ;a1asilas 'e)etrios ;ydones (lissaeus Judaeus 1363 1363 5eorgios Plethon 5e)istos /anuel .hrysoloras 1393 1333 5uarino da Verona 1408 1& , Vittorino da Feltre 1416 U. Padova 1&16 *heodoros 5a2es 1433 U. /antova 1&33 Basilios Bessarion 1436 /ystras 1&36 Johannes Argyropoulos 1444 U. Padova 1&&& 'e)etrios .halcocondyles Pietro 0occa1onella Pelope /ystras 1452 1&+2 9iccolo 6eoniceno 1453 U. Padova 1&+3 /arsilio Ficino 1462 U. Florence 1&62 Janus 6ascaris *ho)as von ;e)pen a ;e)pis U. Padova 1472 1&72 Alexander "egius Jaco1 1en Jehiel 6oans St. Agnes, $%olle 1474 1&7& Johannes Sto88ler .risto8oro 6andino U. <ngolstadt 1476 1&76 Angelo Poliziano 1477 U. Florence 1&77 0udol8 Agricola 5eorgius "er)onymus U. Ferrara 1478 1&7, Jacques 6e8evre d(taples 1480 U. Paris 1&, Johann 0euchlin 1481 U. Poitiers 1&,1 6eo ?uters 1485 U. 6ouvain 1&,+ Jan Standonck 1490 U. Paris 1&3 5uillau)e Bude 1491 U. Paris 1&31 Scipione Fortiguerra 1493 U. Florence 1&33 Ulrich $asius 1501 U. Frei1urg 1+ 1 'esiderius (rasmus /oses Pere2 U. *urin 1506 1+ 6 5irola)o Aleandro 1508 U. Padova 1+ , 0utger 0escius 1513 U. Paris 1+13 Philipp /elanchthon 1514 U. *u1ingen 1+1& *ho)as .ran)er /aarten van 'orp 1515 U. .a)1ridge U. 6ouvain 1+1+ 1+1+ Francois 'u1ois 1516 U. Paris 1+16 Andrea Alciati /atthaeus Adrianus U. Bologna 1518 1+1, Jaco1us 6ato)us Jan van .a)pen 1519 U. 6euven U. -

4 Reformed Orthodoxy

Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology Belt, H. van der Citation Belt, H. van der. (2006, October 4). Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). id7775687 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com 4 Reformed Orthodoxy The period of Reformed orthodoxy extends from the Reformation to the time that liberal theology became predominant in the European churches and universities. During the period the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican churches were the official churches in Protestant countries and religious polemics between Catholicism and Protestantism formed an integral part of the intense political strife that gave birth to modern Europe. Reformed orthodoxy is usually divided into three periods that represent three different stages; there is no watershed between these periods and it is difficult to “ ” determine exact dates. During the period of early orthodoxy the confessional and doctrinal codifications of Reformed theology took place. This period is characterized by polemics against the Counter-Reformation; it starts with the death of the second- generation Reformers (around 1565) and ends in the first decades of the seventeenth century.1 The international Reformed Synod of Dort (1618-1619) is a useful milestone, 2 “ because this synod codified Reformed soteriology. -

Finding Certainty in an Age of Uncertainty the Early Eighteenth-Century Cocceian Turn Towards Natural Theology

Finding certainty in an age of uncertainty The early eighteenth-century Cocceian turn towards natural theology Masterthesis by: Niels Visscher – 3237494 Primary reader: Prof.dr. M. Mostert Secondary reader: Prof.dr. W. Mijnhardt Medieval Studies University Utrecht 19-07-2013 1 Content Preface 3 Introduction 4 Chapter I: The crisis of the Reformed mind 9 The Reformed theological system 9 Scripture and the Reformed articles of faith 10 The intellectual foundations of Reformed theology 12 Reformed theology and the challenge of Cartesianism 13 The challenge of Cartesian philosophy 14 The Voetian response to the new philosophy 15 The Cartesian philosophers 16 The Cocceian theologians 18 The rise of philosophical radicalism 20 Chapter II: Living during the crisis of the Reformed mind 24 A child prodigy 24 The University of Franeker 25 Education at the University of Franeker 27 The status of reason and the divinity of Scripture 28 Minister of the Divine Word 29 Professor of at the University of Franeker 31 The last of the Cartesians 32 Chapter III: Vindicating the divinity of Scripture 34 The Reformed view on natural theology 35 The characteristics of natural theology 36 The new approach to natural theology 37 Prolegomena 38 The doctrine of God 40 Natural religion 41 The necessity and divinity of supernatural revelation 42 Ruardus Andala on natural theology 44 Prolegomena 45 The doctrine of God 46 Natural religion 47 The necessity and divinity of supernatural revelation 48 A turn towards rationalism? 49 Conclusion 51 Bibliography 53 2 Preface Trying to obtain a master’s degree in Medieval Studies by writing a thesis on seventeenth- and eight- eenth-century developments in theology and philosophy – this turn of events will probably amaze many readers. -

'Elke Daad Is Een Werk'

‘Elke daad is een werk’ Alexander Comrie (1706-1774) over de verschillen tussen de remonstrantse en de gereformeerde rechtvaardigingsleer G.A. van den Brink Abstract The Dutch theologian Alexander Comrie (1706-1774) opposed Amyraldism vehemently. He downplayed the role of the act of faith in justification, for ‘every act is a work of man.’ However, Comrie offended many of his colleagues by suggesting that anyone who regarded the act of faith as the instrument involved in justification, was dogmatically speaking to be considered an amyraldian or even an arminian. Comrie was, in turn, accused of antinomianism. In this article the dogmatic position of Comrie is analyzed. His view on the material cause and especially on the formal cause of justification is compared with the views by Arminius, Lubbertus and others. It is concluded that Comrie mistakenly regarded the immediacy of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as fundamental for the Reformed doctrine of justification. 1 Inleiding Toen de Schots-Nederlandse theoloog Alexander Comrie (1706-1774)1 in 1753 zijn verklaring van Zondag 1-7 van de Heidelbergse Catechismus publi- ceerde, brak er een storm van protest los. Geheel onbegrijpelijk was de verbol- genheid niet: Comrie schroomde niet om velen van zijn collega’s te bestempe- len als mensen die, al of niet bewust, een arminiaanse en semipelagiaanse opvatting huldigden ten aanzien van de leer van de rechtvaardiging. De bezorgdheid van Comrie werd ingegeven door de controverse rondom de Zwolse predikant Antonius van der Os (1722-1807).2 Deze was aangeklaagd 1 A.G. Honig, Alexander Comrie, Utrecht 1892; R.A. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. JOHANNES SWARTENHENGST (1644-1711): A DUTCH CARTESIAN IN THE HEAT OF BATTLE ESTER BERTRAND PHD THESIS UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH & FREE UNIVERSITY OF BRUSSELS 2014 2 JOHANNES SWARTENHENGST (1644-1711): A DUTCH CARTESIAN IN THE HEAT OF BATTLE ESTER BERTRAND The painting on the title page, entitled The Stallion, is by the accomplished Dutch painter of equestrian scenes, Philips Wouwerman (1619-1668). In agreement with the Creative Commons Licence this copy was retrieved from the following website: http://www.wouwerman.org/ PHD THESIS UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH & FREE UNIVERSITY OF BRUSSELS JUNE 2014 Funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), the Free University of Brussels, and the University of Edinburgh I, Ester Bertrand, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 95.000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. -

Not a Covenant of Works in Disguise” (Herman Bavinck1): the Place of the Mosaic Covenant in Redemptive History

MAJT 24 (2013): 143-177 “NOT A COVENANT OF WORKS IN DISGUISE” (HERMAN BAVINCK1): THE PLACE OF THE MOSAIC COVENANT IN REDEMPTIVE HISTORY by Robert Letham READERS WILL DOUBTLESS be aware of the argument that the Mosaic covenant is in some way a republication of the covenant of works made by God with Adam before the fall. In recent years, this has been strongly advocated by Meredith Kline and others influenced by his views. In this article I will ask some historical and theological questions of the claim. I will also consider how far Reformed theology, particularly in the period up to the production of the major confessional documents of the Westminster Assembly (1643-47), was of one mind on the question. 2 I will concentrate on the argument itself, without undue reference to persons.3 1. Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, Volume 3: Sin and Salvation in Christ (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 222. 2. Apart from the works of Kline, cited below, others have addressed the matter in some detail - Mark W. Karlberg, “The Search for an Evangelical Consensus on Paul and the Law,” JETS 40 (1997): 563–79; Mark W. Karlberg, “Recovering the Mosaic Covenant as Law and Gospel: J. Mark Beach, John H. Sailhammer, and Jason C. Meyer as Representative Expositors,” EQ 83, no. 3 (2011): 233–50; D. Patrick Ramsey, “In Defense of Moses: A Confessional Critique of Kline and Karlberg,” WTJ 66 (2004): 373–400; Brenton C. Ferry, “Cross-Examining Moses’ Defense: An Answer to Ramsey’s Critique of Kline and Karlberg,” WTJ 67 (2005): 163–68; J. -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C. -

University of Groningen Developments in Structuring Of

University of Groningen Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology van den Belt, Hendrik Published in: Reformation und Rationalität IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Final author's version (accepted by publisher, after peer review) Publication date: 2015 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H. (2015). Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology: The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625) as Example. In H. J. Selderhuis, & E-J. Waschke (Eds.), Reformation und Rationalität (pp. 289-311). (Refo500 Academic Studies; Vol. 17). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 11-02-2018 1 Henk van den Belt 2 3 4 Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology: 5 6 The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625) as Example. 7 8 9 10 11 12 Abstract 13 14 The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625), an influential handbook of Reformed 15 dogmatics, began as a cycle of disputations. -

Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School July 2020 Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789 Stephen Michael Wolfe Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wolfe, Stephen Michael, "Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5344. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5344 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROTESTANT EXPERIENCE AND CONTINUITY OF POLITICAL THOUGHT IN EARLY AMERICA, 1630-1789 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Stephen Michael Wolfe B.S., United States Military Academy (West Point), 2008 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2016, 2018 August 2020 Acknowledgements I owe my interest in politics to my father, who over the years, beginning when I was young, talked with me for countless hours about American politics, usually while driving to one of our outdoor adventures. He has relentlessly inspired, encouraged, and supported me in my various endeavors, from attending West Point to completing graduate school. -

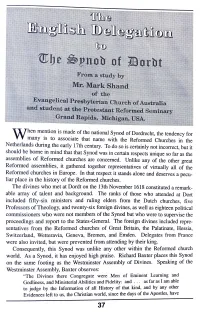

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

Foundations of Psychology by Herman Bavinck

Foundations of Psychology Herman Bavinck Translated by Jack Vanden Born, Nelson D. Kloosterman, and John Bolt Edited by John Bolt Author’s Preface to the Second Edition1 It is now many years since the Foundations of Psychology appeared and it is long out of print.2 I had intended to issue a second, enlarged edition but the pressures of other work prevented it. It would be too bad if this little book disappeared from the psychological literature. The foundations described in the book have had my lifelong acceptance and they remain powerful principles deserving use and expression alongside empirical psy- chology. Herman Bavinck, 1921 1 Ed. note: This text was dictated by Bavinck “on his sickbed” to Valentijn Hepp, and is the opening paragraph of Hepp’s own foreword to the second, revised edition of Beginselen der Psychologie [Foundations of Psychology] (Kampen: Kok, 1923), 5. The first edition contains no preface. 2 Ed. note: The first edition was published by Kok (Kampen) in 1897. Contents Editor’s Preface �����������������������������������������������������������������������ix Translator’s Introduction: Bavinck’s Motives �������������������������� xv § 1� The Definition of Psychology ���������������������������������������������1 § 2� The Method of Psychology �������������������������������������������������5 § 3� The History of Psychology �����������������������������������������������19 Greek Psychology .................................................................19 Historic Christian Psychology ..............................................22