Bullet Time As Microgenre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Copyrighted Material

9781405170550_6_ind.qxd 16/10/2008 17:02 Page 432 INDEX 4 Little Girls (1997) 93 action-adventure movie 147, 149, 254, 339, 348, 352, 392–3, 396–7, 8 Mile (2002) 396–7 259, 276, 287–8, 298–9, 410 402–3 20th Century-Fox 21, 30, 34, 40–2, 73, actualities 106, 364, 410 Against All Odds (1984) 289 149, 184, 204–5, 281, 335 ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Agar, John 268 25th Hour, The (2002) 98 Power) 337, 410 Aghdashloo, Shohreh 75 27 Dresses (2008) 353 ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Ahn, Philip 130 28 Days (2000) 293 398–9, 410 AIDS 99, 329, 334, 336–40 48 Hours (1982) 91 Adachi, Jeff 139 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power see 100-to-1 Shot, The (1906) 174 Adams, Evan 118–19 ACT-UP 300 (2007) 74, 298, 300 ADC (American-Arab Anti- AIM (American Indian Movement) 111, Discrimination Committee) 73–4, 116–17, 410 Abbott and Costello 268 410 Air Force (1943) 268 ABC 340 Addams Family, The (1991) 156 Akins, Zoe 388–9 Abie’s Irish Rose (stage) 57 Addams Family Values (1993) 156 Aladdin (1992) 73–4, 246 Abilities United Productions 384 Adiarte, Patrick 72 Alba, Jessica 76, 155, 159 ability 359–84, 410 adult Western 111, 410 Albert, Eddie 72 ableism 361, 381, 410 Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The (TV) Albert, Edward 375 Abominable Dr Phibes, The (1971) 284 Alexie, Sherman 117–18 365 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Algie, the Miner (1912) 312 Abraham, F. Murray 75, 76 COPYRIGHTEDDesert, The (1994) 348 MATERIALAli (2001) 96 Academy Awards (Oscars) 29, 58, 63, Adventures of Sebastian Cole, The (1998) Alice (1990) 130 67, 72, 75, 83, 92, 93, -

On Visual Art and Camouflage

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Faculty Publications Faculty Work 1978 On Visual Art and Camouflage Roy R. Behrens University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1978 The MIT Press Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/art_facpub Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Behrens, Roy R., "On Visual Art and Camouflage" (1978). Faculty Publications. 7. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/art_facpub/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leonardo. Vol. 11, pp. 203-204. 0024--094X/78/070 I -0203S02.00/0 6 Pergamon Press Ltd. 1978. Printed in Great Britain. ON VISUAL ART AND CAMOUFLAGE Roy R. Behrens* In a number of books on visual fine art and design [ 1, 21, countershading makes a 3-dimensional object seem flat, there is mention of the kinship between camouflage and while normal shading in flat paintings can make a painting, but no one has, to my knowledge, pursued it. I depicted object appear to be 3-dimensional. He also have intermittently researched this relationship for discussed the function of disruptive patterning, in which several years, and my initial observations have recently even the most brilliant colors may contribute to the been published [3]. Now I have been awarded a faculty destruction of an animal’s outline. While Thayer’s research grant from the Graduate School of the description of countershading is still respected, his book is University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to pursue this considered somewhat fanciful because of exaggerated subject in depth. -

LS28 Camouflage and Mimicry Follow up Student #2

Follow-up Activity: For Students Life Science 28: Camouflage and Mimicry Introduction: In this lesson, camouflage & mimicry were explored as examples of adaptations adopted by animals to increase their chances of survival. What can an animal do to keep from being a predator's dinner? To survive, some animals use camouflage so they can better blend in with their surroundings. Camouflage is a set of colorings or markings on an animal that help it to blend in with its surroundings, or habitat, and prevent it from being recognized as potential prey. Activity: Candy Camouflage In this science activity, you and your friends will become the hungry predators and you'll hunt for different colored candies. But it may not be as easy as it sounds—some of your prey will be camouflaged by their habitats. Are you ready for the challenge? Materials: • Six plastic bags (one bag for M&Ms; 5 bags for Skittles, separated by color) • Plain M&Ms; at least 10 of each color (at least two 1.69-ounce packages may be needed) • Skittles; at least 60 of each color (one 16-oz package) • Metal pie tin or other deep plate • Cups for collecting candies during the hunt; one cup per predator • Timer • Data charts (attached) • 2-4 Volunteer predators to be hungry M&Ms-feasting birds Preparation: 1. Place 10 M&Ms of each color (yellow, blue, green, brown, red, orange) into one plastic bag 2. Place 60 Skittles of each color (orange, green, red, yellow, purple) into separate plastic bags. This means you will have 5 separate bags of Skittles: one bag containing only red, one bag containing only orange, one bag containing green, one bag of purple and one bag of yellow) 3. -

COM 320, History of the Moving Image–The Origins of Editing Styles And

COM 320, History of Film–The Origins of Editing Styles and Techniques I. The Beginnings of Classical/Hollywood Editing (“Invisible Editing”) 1. The invisible cut…Action is continuous and fluid across cuts 2. Intercutting (between 2+ different spaces; also called parallel editing or crosscutting) -e.g., lack of intercutting?: The Life of An American Fireman (1903) -e.g., D. W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) (boxing match vs. girl/Chinese man encounter) 3. Analytical editing -Breaks a single space into separate framings, after establishing shot 4. Continguity editing…Movement from space to space -e.g., Rescued by Rover (1905) 5. Specific techniques 1. Cut on action 2, Match cut (vs. orientation cut?) 3. 180-degree system (violated in Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)) 4. Point of view (POV) 5. Eyeline match (depending on Kuleshov Effect, actually) 6. Shot/reverse shot II. Soviet Montage Editing (“In-Your-Face Editing”) 1. Many shots 2. Rapid cutting—like Abel Gance 3. Thematic montage 4. Creative geography -Later example—Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds 5. Kuleshov Effect -Established (??) by Lev Kuleshov in a series of experiments (poorly documented, however) -Nature of the “Kuleshov Effect”—Even without establishing shot, the viewer may infer spatial or temporal continuity from shots of separate elements; his supposed early “test” used essentially an eyeline match: -e.g., man + bowl of soup = hunger man + woman in coffin = sorrow man + little girl with teddy bear = love 6. Intercutting—expanded use from Griffith 7. Contradictory space -Shots of same event contradict one another (e.g., plate smashing in Potemkin) 8. Graphic contrasts -Distinct change in composition or action (e.g., Odessa step sequence in Potemkin) 9. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Robert De Niro's Raging Bull

003.TAIT_20.1_TAIT 11-05-12 9:17 AM Page 20 R. COLIN TAIT ROBERT DE NIRO’S RAGING BULL: THE HISTORY OF A PERFORMANCE AND A PERFORMANCE OF HISTORY Résumé: Cet article fait une utilisation des archives de Robert De Niro, récemment acquises par le Harry Ransom Center, pour fournir une analyse théorique et histo- rique de la contribution singulière de l’acteur au film Raging Bull (Martin Scorcese, 1980). En utilisant les notes considérables de De Niro, cet article désire montrer que le travail de cheminement du comédien s’est étendu de la pré à la postproduction, ce qui est particulièrement bien démontré par la contribution significative mais non mentionnée au générique, de l’acteur au scénario. La performance de De Niro brouille les frontières des classes de l’auteur, de la « star » et du travail de collabo- ration et permet de faire un portrait plus nuancé du travail de réalisation d’un film. Cet article dresse le catalogue du processus, durant près de six ans, entrepris par le comédien pour jouer le rôle du boxeur Jacke LaMotta : De la phase d’écriture du scénario à sa victoire aux Oscars, en passant par l’entrainement d’un an à la boxe et par la prise de soixante livres. Enfin, en se fondant sur des données concrètes qui sont restées jusqu’à maintenant inaccessibles, en raison de la modestie et du désir du comédien de conserver sa vie privée, cet article apporte une nouvelle perspective pour considérer la contribution importante de De Niro à l’histoire américaine du jeu d’acteur. -

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. How, then, can we describe the affective and temporal experience of digital media, whose algorithmic processes elude conscious thought and yet form the (im)material conditions of much of our life today? In order to address this question, this chapter examines several examples of digital media works (films, games) that can serve as central mediators of the shift to a properly post-cinematic regime, focusing particularly on the aesthetic dimensions of the popular and transmedial “bullet time” effect. Looking primarily at the first Matrix film | 1 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality (1999), as well as digital games like the Max Payne series (2001; 2003; 2012), I seek to explore how the use of bullet time serves to highlight the medial transformation of temporality and affect that takes place with the advent of the digital—how it establishes an alternative configuration of perception and agency, perhaps unprecedented in the cinematic age that was dominated by what Deleuze has called the “movement-image.”[1] 1. -

Movie Museum JANUARY 2012 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum JANUARY 2012 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY 2 Hawaii Premieres! WATERBOYS PENGUINS IN THE SKY– CRADLE SONG 2 Hawaii Premieres! LATE BLOOMERS (2001-Japan) ASAHIYAMA ZOO aka Canción de cuna NOT WITHOUT YOU (2006-Switzerland) in Japanese with English (2008-Japan) (1994-Spain) aka Bu Neng Mei You Ni in Swiss German with English subtitles & in widescreen in Japanese with English in Spanish with English (2009-Taiwan) subtitles & in widescreen with Satoshi Tsumabuki, subtitles & in widescreen subtitles & in widescreen in Hakka/Mandarin w/English with Stephanie Glaser. Hiroshi Tamaki, Akifumi with Toshiyuki Nishida, 12:00 & 7:30pm only subtitles & in widescreen 12:00, 3:15 & 6:30pm only Miura, Naoto Takenaka, Yasuhi Nakamura, Ai Maeda, ---------------------------------- 12:00, 3:15 & 6:30pm only ---------------------------------- Koen Kondo, Kaori Manabe. Keiko Horiuchi, Zen Kajihara. I KNOW WHERE I'M ---------------------------------- NOT WITHOUT YOU GOING! (1945-British) LATE BLOOMERS aka Bu Neng Mei You Ni Directed and Co-written by Directed by with Wendy Hiller, Roger (2006-Switzerland) (2009-Taiwan) Shinobu Yaguchi. Masahiko Tsugawa. Livesey, Finlay Currie. in Swiss German with English in Hakka/Mandarin w/English Directed by Michael Powell subtitles & in widescreen subtitles & in widescreen 12:00, 1:45, 3:30, 5:15, 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 and Emeric Pressburger. with Stephanie Glaser. 1:30, 4:45 & 8:00pm only 2:00, 3:45 & 5:30pm only 5 7:00 & 8:45pm 6 & 8:30pm 7 8 1:45, 5:00 & 8:15pm only 9 2 Hawaii Premieres! Martin Luther King Jr. Day Hawaii Premiere! Hawaii Premiere! MONEYBALL DISPATCH MONSIEUR BATIGNOLE THE LAST LIONS 2 Hawaii Premieres! (2011) THE FIRST GRADER (2011) (2002-France) in widescreen (2011-US/Botswana) in widescreen in French/German w/English in widescreen (2010-UK/US/Kenya) with Michael Bershad. -

The Making of Enter the Matrix

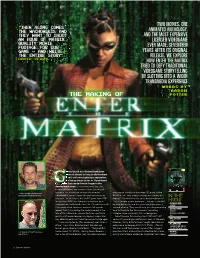

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Copyright Undertaking

Copyright Undertaking This thesis is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. By reading and using the thesis, the reader understands and agrees to the following terms: 1. The reader will abide by the rules and legal ordinances governing copyright regarding the use of the thesis. 2. The reader will use the thesis for the purpose of research or private study only and not for distribution or further reproduction or any other purpose. 3. The reader agrees to indemnify and hold the University harmless from and against any loss, damage, cost, liability or expenses arising from copyright infringement or unauthorized usage. IMPORTANT If you have reasons to believe that any materials in this thesis are deemed not suitable to be distributed in this form, or a copyright owner having difficulty with the material being included in our database, please contact [email protected] providing details. The Library will look into your claim and consider taking remedial action upon receipt of the written requests. Pao Yue-kong Library, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong http://www.lib.polyu.edu.hk WAR AND WILL: A MULTISEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF METAL GEAR SOLID 4 CARMAN NG Ph.D The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 2017 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of English War and Will: A Multisemiotic Analysis of Metal Gear Solid 4 Carman Ng A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 For Iris and Benjamin, my parents and mentors, who have taught me the courage to seek knowledge and truths among warring selves and thoughts.