Luke Wadding and Irish Diplomatic Activity in Seventeenth-Century Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siochru-Atrocity

The Past and Present Society Atrocity, Codes of Conduct and the Irish in the British Civil Wars 1641-1653 Author(s): Micheál Ó. Siochrú Source: Past & Present, No. 195 (May, 2007), pp. 55-86 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25096669 Accessed: 28-03-2017 16:22 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford University Press, The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past & Present This content downloaded from 98.228.179.226 on Tue, 28 Mar 2017 16:22:58 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms ATROCITY, CODES OF CONDUCT AND THE IRISH IN THE BRITISH CIVIL WARS 1641-1653* To introduce the principle of moderation into the theory of war itself would always lead to logical absurdity. Clausewitz1 In Ireland, Oliver Cromwell's name will for ever be associated with the storming of the towns of Drogheda and Wexford in the autumn of 1649. The massacre of troops and civilians in both cases shocked contemporary Irish opinion and left a deep legacy of bitterness towards English colonial rule. -

Lot and His Daughters Pen and Brown Ink and Brown Wash, with Traces of Framing Lines in Brown Ink

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri GUERCINO (Cento 1591 - Bologna 1666) Lot and his Daughters Pen and brown ink and brown wash, with traces of framing lines in brown ink. Laid down on an 18th century English mount, inscribed Guercino at the bottom. Numbered 544. at the upper right of the mount. 180 x 235 mm. (7 1/8 x 8 7/8 in.) This drawing is a preparatory compositional study for one of the most significant works of Guercino’s early career; the large canvas of Lot and His Daughters painted in 1617 for Cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi, the archbishop of Bologna and later Pope Gregory XV, and today in the monastery of San Lorenzo at El Escorial, near Madrid. This was one of three paintings commissioned from Guercino by Cardinal Ludovisi executed in 1617, the others being a Return of the Prodigal Son and a Susanna and the Elders. The Lot and His Daughters is recorded in inventories of the Villa Ludovisi in Rome in 1623 and 1633, but in 1664 both it and the Susanna and the Elders were presented by Prince Niccolò Ludovisi, nephew of Gregory XV, to King Phillip IV of Spain. The two paintings were placed in the Escorial, where the Lot and His Daughters remains today, while the Susanna and the Elders was transferred in 1814 to the Palacio Real in Madrid and is now in the Prado. Painted when the artist was in his late twenties, the Lot and his Daughters is thought to have been the first of the four Ludovisi pictures to be painted by Guercino. -

Apostolic Lines of Succession-10-2018

Apostolic Lines of Succession for ++Michael David Callahan, DD, OCR, OCarm. The Catholic Church in America “Have you an apostolic succession? Unfold the line of your bishops.” Tertullian, 3rd century A.D. A special visible expression of Apostolic Succession is given in the consecration/ ordination of a bishop through the laying on of hands by other bishops who have, themselves, been ordained in the same manner through a succession of bishops leading back to the apostles of Jesus. The role of the bishop must always be understood within the context of the authentic handing on of the faith from one generation to the next generation of the whole Church, beginning with the Christian community of the time of the Apostles. Thus, as the Church is the continuation of the apostolic community, so the bishops are the continuation of the ministry of the college of the apostles of Jesus within that apostolic community. It is essentially collegial rather than monarchical. This tradition is affirmed in the teaching ministry of Church leadership, and authentically celebrated in the sacraments, with particular attention to the sacrament of holy orders (ordination) and the laying on of hands. Apostolic Succession is the belief of Catholic Christians that the bishops are successors of the original apostles of Jesus. This is understood as the bishops being ordained into the episcopal collegium or “sacramental order.” As bishops are by tradition consecrated by at least three other bishops, the actual number of lists of succession can become quite substantial. Listed here are three lines of succession: 1. From Saints Paul and Linus Succession through Archbishop Baladad 2. -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

556251Syl .Pdf

PROPOSAL (REVISED) FOR RUTGERS SAS CURRICULUM COMMITTEE PAPAL ROME AND ITS PEOPLE, 1500-PRESENT: A SELECT HISTORY ARTS & SCIENCES INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES 01:556:251 Online course, proposed for spring semester 2014 T. Corey Brennan (Department of Classics; Rutgers—NB) DESCRIPTION (FOR CATALOG) A case-study approach toward select aspects of the social, cultural, intellectual and political history of the early modern and modern Popes, with a particular focus on their relationship to the city of Rome. Highlights the reigns of Popes Gregory XIII Boncompagni (1572-1585) and Gregory XV Ludovisi (1621-1623), and their subsequent family history to the present day. Some course lectures pre-recorded on-site in Rome. COURSE OBJECTIVES 1) Gain a fundamental understanding of the history of the Papacy in outline and the significance of that institution from the early modern period to the present day, in the context especially of Italian and wider European history 2) Understand on a basic level the implications of Papal urban interventions in Rome, and the Popes’ more significant patronage and preservation efforts in that city 3) Gain a broad familiarity with the most important Italian families of the Papal nobility who have made a substantial physical contribution to the city of Rome 4) Appreciate the range of primary sources that can be critically employed and analyzed for Papal history, including iconographic material that ranges beyond painting and sculpture to include numismatic evidence, historic photographs and newsreels LEARNING GOALS (THEORETICAL) -

Barquilla De La Santa Maria BULLETIN of the Catholic Record Society Diocese of Columbus

Barquilla de la Santa Maria BULLETIN of the Catholic Record Society Diocese of Columbus Vol. X:XV, No. 9 Sept. 3: Beatification of Pope Pius IX September, 2000 Episcopal Lineages of the Bishops of Columbus Part 1: Bishop Elwell The Church we profess to be one, holy, catholic, Bishops of Columbus descend. Looking back and apostolic. Regarding the last ofthese marks, before his time, it was a last minute change in his the Second Vatican Council said the following in consecrator, not discovered until the 1960s, that Lumen Gentium, The Dogmatic Constitution on caused all lineages written until that time to be in the Church. "That divine mission, which was error. committed by Christ to the apostles, is destined to last until the end of the world ... For that very Interest in episcopal lineage in the United States reason the apostles were careful to appoint was shown as early as 1916, when articles successors... They accordingly designated such focused on the subject in the Catholic Historical men and then made the ruling that likewise on Review. Study of the subject was facilitated in their death other proven men should take over 1940 by the publication by Catholic University's their ministry. Among those various offices Rev. Joseph Bernard Code of the Dictionary of which have been exercised in the Church from the American Hierarchy (New York: the earliest times the chiefplace, according to the Longmans, Green and Co.). Seminarians at Mt. witness of tradition, is held by the function of St. Mary Seminary of the West in Cincinnati those who, through their appointment to the published an article in the April, 1941 issue of dignity and responsibility of bishop, and in virtue their Seminary Studies titled, "The Episcopal consequently of the unbroken succession, going Lineage of the Hierarchy of the United States". -

The Politics of Catholic Versus Protestant and Understandings of Personal Affairs in Restoration Ireland

Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies, n. 5 (2015), pp. 171-181 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/SIJIS-2239-3978-16344 The Politics of Catholic versus Protestant and Understandings of Personal Affairs in Restoration Ireland Danielle McCormack Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań (<[email protected]>) Abstract: Between 1641 and 1652, Ireland was ravaged by war and monarchy was replaced by the Cromwellian Commonwealth and Protector- ate regimes. The armies of Oliver Cromwell conquered Ireland and Catholic landowners were dispossessed and transplanted. The res- toration of the Stuarts in 1660 opened up the prospect that these changes might be undone. Catholics set the tone for debate in the 1660s, challenging Protestant dominance. Catholic assertiveness led to panic throughout the Protestant colonies, and the interpretation of domestic strife and personal tragedy in the context of competition between Catholic and Protestant. This article will recreate the climate of mistrust which obtained within the community before moving to a unique analysis of the impact which this could have on the family. Keywords: Early modern Ireland, marriage, political history, sectari- anism, Stuart restoration On 29 May 1660, the Stuart monarchy was officially restored in Ireland, Scotland and England, following eleven years of Interregnum. Throughout the Interregnum, the monarch, Charles II, who had been crowned king of the three kingdoms by the Scots in 1649, had been in exile on the European con- tinent. Officially, the Stuart restoration marked a return to the status quo ante and the obliteration of the constitutional changes that had been wrought dur- ing the 1650s by the Cromwellian Commonwealth and Protectorate regimes. -

The Case of Guercino

arts Article Marketing and Self-Promotion in Early Modern Painting: The Case of Guercino Daniel M. Unger The Department of the Arts, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva 8410501, Israel; [email protected] Abstract: This article focuses on Guercino’s Return of the Prodigal Son, commissioned in the name of Cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi and on his marketing choices. This is a case study in terms of self- promotion tactics employed by an ambitious artist. My argument is that one finds in the painting a secondary and more sophisticated level of interpretation, which relates to the relationship between the painter and his patron. To the most traditional iconography of the scene, Guercino added musicians and spectators, thus positioning the entire composition in the theatre. One of the musicians is depicted in a way that casts him as a representative of the painter. The patron understood Guercino’s intentions and commissioned what became Guercino’s most important artworks. It was Guercino’s ability of shifting the attention of a given iconography and deliver current political meaning that is discernible in his Roman works commissioned by the same Cardinal Ludovisi who was elected Pope Gregory XV. Keywords: Guercino; Gregory XV; prodigal son; early modern theatre; self-presentation 1. Introduction Citation: Unger, Daniel M. 2021. Today we may confidently assert the extent to which Guercino’s career was impacted Marketing and Self-Promotion in by Pope Gregory XV (Alessandro Ludovisi 1554–1623). In 1621, immediately after his Early Modern Painting: The Case of 1 Guercino. -

LUKE WADDING Irishman & Franciscan by FATHER LUCIUS Mcclean O.F.M

FATHER LUKE WADDING Irishman & Franciscan by FATHER LUCIUS McCLEAN O.F.M. A Tercentenary Tribute ASSISI PRESS DUBLIN 1956 All the Iacts in this brief life of Father Luke Wadding are taken from the Wadding Papers edited by Father Brendan Jennings, 0.F.M.: and published by the Irish Manu- scripts Commission, and from Saint Isido?,e's Chzwch and College of the Irish Franciscans Rome, by Father Hubert Quiran, 0 F.M. Nihil obsiat: Michael O'Halloran, Censor Deputatus. Zmprimi potest : Joannes Carolus, Archiep. Dubiinensis, Hibemiae Primas, die 29 Maii, 1956. Nihil obstat: P. Victor Sheppard, O.F.M., Censor Deputatus. Imprimatur: P. Hubertus Quinn, O.F.M., Min. Provl., in festo Ascensionis Domini, 1% 6. FRESCO BY EMrlNUELE DA COhlO SHOWING FATHER WADDING AND HIS COMPANIONS ENGAGED IN THEIR LITERARY LABOURS FATHER LUKE WADDING IRISHMAN AND FRANCISCAN TERCENTENARY OF AN EMIGRANT T WAS POPE PIUS XI who paid the tribute to our nation of saying that Irishmen were like God's fresh air ; they are everywhere. Driven Ifrom home bv necessitv or lured abroad by the green hills of faf-off plac&, urged on by ap&tolic zeal or compelled by an inner need for travel and adventure, we are a nation of wanderers. To leave our native land is traditional with us; to return to it is a desire no Irishman ever loses. Over three hundred years ago a young boy left Waterford, never to return to the country for which he Lived and which, in the coming year, will honour him as one of its most outstanding and loyal sons, perhaps one of its most influential representatives and its greatest emigrant and exile. -

Preface (Brief Explanation of What This Thing Is and Isn't)

Preface In his lifetime, Marc’Antonio Pasqualini’s international fame rested on his singing, and at present count his name appears as the composer on only forty-eight seventeenth-century copies of chamber cantatas.1 At his death in 1691, however, the singer’s personal music library, which included eight volumes of cantatas written for the most part in his own hand, passed to Urbano Barberini, prince of Palestrina and the great-nephew of Marc’Antonio’s patron, Cardinal Antonio Barberini, the younger.2 This is the reason they were among the 115 manuscripts of music that the Vatican Library acquired when it purchased the Barberini library in 1902. In the twentieth century, several music historians considered these eight volumes as copies of music by unknown composers—or by Luigi Rossi—that the singer had written out for his own use.3 But they contain not only concordances with forty-two of the forty-eight cantatas that bear Pasqualini’s name, but three of them also preserve, not duplicate copies, but rather compositional drafts for many of the forty-eight and for nearly another one hundred cantatas. In addition, Pasqualini’s hand as composer and editor shows up in several other Barberini music manuscripts, indicating that these, too, must have been in his possession fifty to sixty years before his death. The Annotated List of Sources, part A (in the appendices to this catalogue) summarizes the eleven principal sources of his chamber cantatas, which are 1 Inventoried in Margaret Murata, “Pasqualini riconosciuto,” in "Et facciam dolçi canti." Studi in onore di Agostino Ziino in occasione del suo 65° compleanno, ed. -

1 Caravaggio and a Neuroarthistory Of

CARAVAGGIO AND A NEUROARTHISTORY OF ENGAGEMENT Kajsa Berg A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia September 2009 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior written consent. 1 Abstract ABSTRACT John Onians, David Freedberg and Norman Bryson have all suggested that neuroscience may be particularly useful in examining emotional responses to art. This thesis presents a neuroarthistorical approach to viewer engagement in order to examine Caravaggio’s paintings and the responses of early-seventeenth-century viewers in Rome. Data concerning mirror neurons suggests that people engaged empathetically with Caravaggio’s paintings because of his innovative use of movement. While spiritual exercises have been connected to Caravaggio’s interpretation of subject matter, knowledge about neural plasticity (how the brain changes as a result of experience and training), indicates that people who continually practiced these exercises would be more susceptible to emotionally engaging imagery. The thesis develops Baxandall’s concept of the ‘period eye’ in order to demonstrate that neuroscience is useful in context specific art-historical queries. Applying data concerning the ‘contextual brain’ facilitates the examination of both the cognitive skills and the emotional factors involved in viewer engagement. The skilful rendering of gestures and expressions was a part of the artist’s repertoire and Artemisia Gentileschi’s adaptation of the violent action emphasised in Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes testifies to her engagement with his painting. -

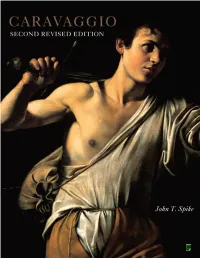

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio.