Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice in Mexico

Venice in Mexico dda25091 dda25091 Baroque Concertos by Facco andVivaldi CD duration: 60.34 Total ©2010 Diversions LLC www.divineartrecords.com www.divine-art.co.uk Brandon, VT (USA) and Doddington, UK Divine Art Record Company, Venice in Mexico : Concertos by Facco and Vivaldi in Mexico : Concertos by Facco Venice Giacomo Facco (1676-1753) Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Mexican Baroque Orchestra : Miguel Lawrence Concerto in E minor, “Pensieri Adriarmonici” Concerto in C major for sopranino recorder, for violin, strings and basso continuo, Op. 1 No. 1 strings and basso continuo, RV.443 1. Allegro [3.25] 2. Adagio [2.27] 3. Allegro [2.48] 13. Allegro [3.31] 14. Largo [3.33] 9. Allegro molto [2.52] Concerto in A major, “Pensieri Adriarmonici” Concerto in D minor for strings and basso continuo, RV.127 for violin, strings and basso continuo, Op. 1 No. 5 16. Allegro [1.36] 17. Largo [0.58] 18. Allegro [1.12] ℗ 4. Allegro [2.56] 5. Grave [3.03] 6. Allegro [2.08] 2010 R. G. de Canales Concerto in C major for psaltery, strings and basso continuo, RV.425 Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) 19. Allegro [3.06] 20. Largo [2.52] 21. Allegro [2.32] Concerto in D major, for strings and basso continuo, RV.121 7. Allegro molto [2.14] 8. Adagio [1.22] 9. Allegro [1.46] Concerto in A minor for sopranino recorder, strings and basso continuo, RV.445 Concerto in A minor “L'estro Armonico”. 22. Allegro [4.17] 23. Largo [2.01] 24. Allegro [3.29] for violin, strings and basso continuo, Op. -

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

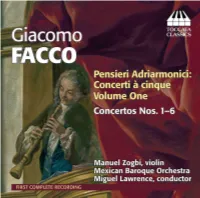

Toccata Classics TOCC0202 Notes

P GIACOMO FACCO: A VENETIAN MUSICIAN AHEAD OF HIS TIME by Betty Luisa Zanolli Fabila Facco is the composer whom I most admire: not only was he the last paladin of the pre-Classical, he looked upon the threshold of 1770 and didn’t perceive the ‘Baroque’ that encircled it. He projected himself towards a future unknown to him and which, a century after, was to be called nineteenth-century Romanticism. His ‘adagios’ and cantatas are the proof. Uberto Zanolli1 Giacomo Facco (1676–1753) is a missing link in the history of music, a musician whose work had to wait 250 years to be rescued from oblivion. This is the story. At the beginning of the 1960s Gonzalo Obregón, curator of the Archive of the Vizcainas College in Mexico City, was organising a cupboard in the compound when suddenly he was hit by a package falling from one of the shelves. It was material he had never seen before, something not included in the catalogue of documents in the College, and completely different in nature from the other materials contained in the Archive: a set of ten little books bound in leather, which contained the parts of a musical work, the Pensieri Adriarmonici o vero Concerti a cinque, Tre Violini, Alto Viola, Violoncello e Basso per il Cembalo, Op. 1 of Giacomo Facco. Obregón’s interest was piqued in knowing who this composer was and why his works were in the Archive. He went to a friend, Luis Vargas y Vargas, a doctor of radiology by profession and an amateur of music and painting, but he had no idea who Facco might have been, either. -

Cechy Weneckie W Pensieri Adriarmonici Giacoma Facca*

10.2478/v10075-012-0014-6 ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS MARIAE CURIE-SKã ODOWSKA LUBLIN – POLONIA VOL. IX, 2 SECTIO L 2011 Instytut Muzykologii UJ PIOTR WILK Cechy weneckie w Pensieri adriarmonici Giacoma Facca* Venetian Features in Giacomo Facco’s Pensieri adriarmonici W roku 1716 i 1719 w amsterdamskiej o¿ cynie Rogera ukazaáy siĊ kolejno dwie ksiĊgi koncertów fantazyjnie zatytuáowanych Pensieri adriarmonici. Choü ich autor – Giacomo Facco (1676-1753) – najbardziej wpáywowy Wáoch na Póá- wyspie Iberyjskim przed przybyciem Farinellego, znany byá od dawna z haseá w muzycznych leksykonach Walthera, Fétisa, Eitnera i Riemanna1, jego twór- czoĞü instrumentalna wciąĪ pozostaje bliĪej niezbadana2. Urodziá siĊ w Marsango * Praca naukowa ¿ nansowana ze Ğrodków MNiSW na naukĊ w latach 2007-2010 jako projekt badawczy. 1 Zob. J. G. Walther, Musicalisches Lexicon oder Musicalische Bibliothek, Lipsk 1732, s. 238; F. J. Fétis, Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie générale de la musique, wyd. 2 popr., t. 3, Bruksela 1866, s. 176; R. Eitner, Biogra¿ sch-Bibliographisches Quellen-Lexikon der Musiker und Musikgelehrten, wyd. 2 popr., t. 3, Graz 1959, s. 379-380; H. Riemann, Riemann Musik Lexikon, t. 2, Moguncja 1959, s. 484. Hasáa Facco brakuje w Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, red. F. Blume, Kassel 1949-79 (pierwsza edycja). 2 Nie znajdziemy Īadnej wzmianki na temat Facca w najwaĪniejszych monogra¿ ach dotyczących koncertu w XVIII w. Por. A. Hutchings, The Baroque Concerto, Londyn 1961; Ch. White, From Vivaldi to Viotti. A history of the early classical violin concerto, Filadel¿ a 1992, S. McVeigh, J. Hirshberg, The Italian Solo Concerto, 1700-1760. Rhetorical Strategies and Style History, Woodbridge 2004; The Cambridge Companion to the Concerto, red. -

Toronto Early Music Centre Distributed Free to TEMC Members - Cost to Non-Members Is $2.00 Toronto Early Music News Contents of Vol

Toronto Early Music News Volume 27, No. 2 June ’11 - August ’11 a quarterly bulletin of the Toronto Early Music Centre Distributed free to TEMC members - Cost to non-members is $2.00 Toronto Early Music News Contents of Vol. 27 no. 2 Calendar of Forthcoming Events is a quarterly bulletin of the Toronto Early Music Centre (TEMC) . Opinions expressed in June . 2 it are those of the authors and may not be endorsed by the Toronto Early Music Centre . Free Tafelmusik Baroque Summer Institute (TBSI) Concerts 2011 . 4 Unsolicited manuscripts, letters, etc . are welcome, as is any information about early 27th annual Early Music Fair . 6 music concerts, events, recordings and copies of recordings for review . The deadline for the News Items the next issue (September ’11–November ’11) is August 12, 2011 . Speak Up! . 7 Subscription is free with membership to the Toronto Early Music Centre . For rates and Toronto Early Music Centre’s Telephone # 416-464-7610 . 7 other membership benefits, please call 416-464-7610, send e-mail to [email protected] E-mail News And Updates . 7 or write to us at the Toronto Early Music Centre (TEMC), P.O. Box 714, Station P, Have You Been Wondering If Your TEMC Membership Has Expired? . 7 Toronto, ON M5S 2Y4 . Web site: http://www.interlog.com/~temc . Medieval & Renaissance Reference Website . 8 Toronto Early Music Centre The TEMC Vocal Circle . 8 Board of Directors Prima la musica . 9 CanadaCD .ca . 9 Frank Nakashima, President Michael Lerner, Secretary Make A Donation . 10 Kathy Edwards, Treasurer TEMC Newsletter Online Instructions . -

Italian Baroque Instrumental Music

their pitch must have been close to the modern standard a 440 Hz. I am delighted to report, therefore, that this higher pitch is adopted in La Serenissima’s recital The rise of the North Italian violin concerto, vol.3 (Avie av 2154, rec 2008, 78 Ј )—even if, as the programme booklet admits, it is not what Locatelli would have expected in Amsterdam. For most of the music the violins are multi- plied three or four apiece, which raises another general question of performance practice: when are the accompa- nying ‘ ripieno’ parts in concertos intended for single players and when is it legitimate to use more? The solu- Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/em/article/37/4/689/493954 by guest on 27 September 2021 tions adopted by La Serenissima seem perfectly accept- able, although it is hard to see how there could have been more than two to a part in Vivaldi’s rv 562a at the celebra- tory concert in Amsterdam in 1738, given that there is only one copy of each part-book in the set used on that occasion. Le Cène’s 1735 publication of Locatelli’s op.4 includes separate part-books for two solo violins and two ripieno violins, and the instruction ‘ un Solo Violino ’ for ripieno violin 1 at one point in no.9 implies that the part is expected to be doubled elsewhere. However, in the con- certo for four violins (op. 4 no. 12) the ripieno violin parts must be taken by single players — as is done on this recording — since they have to share part-books with solo violins 3 and 4 respectively (the parts are printed on fac- ing pages, piano-duet fashion). -

'New' Cello Concertos by Nicola Porpora

Musica Iagellonica 2020 ISSN 1233–9679 eISSN 2545-0360 Piotr Wilk ( Jagiellonian University in Kraków) ‘New’ Cello Concertos by Nicola Porpora* Nicola Antonio Porpora (1686–1768) went down in history primarily as an opera composer and an excellent singing teacher, who educated the most eminent late Baroque castratos — Farinelli and Caffarelli. His fame in the field of vocal music went far beyond his native Naples. Strong competition from Domenico Sarri, Leonardo Vinci and Leonardo Leo made Porpora look for success for his operas in Rome, Munich, Venice, London, Dresden and Vienna. All the ups and downs in his vocal (not only stage, but also religious) out- put have long been the subject of detailed studies. 1 Less frequently, however, * This article was written with the support of the National Science Centre, Poland, re- search project No 2016/21/B/HS2/00741. 1 Marietta Amstad, “Das berühmte Notenblatt des Porpora: die Fundamentalübungen der Belcanto Schule”, Musica, 23 (1969); Michael F. Robinson, “Porpora’s Operas for Lon- don, 1733–1736”, Soundings, 2 (1971–2); Everett Lavern Sutton, “The Solo Vocal Works of Nicola Porpora: an Annotated Thematic Catalogue” (Ph. diss., University of Minnesota, 1974); Michael F. Robinson, “How to Demonstrate Virtue: the Case of Porpora’s Two Settings of Mitridate”, Studies in Music from the University of Western Ontario, 7 (1982); Stefano Aresi, “Il Polifemo di N. A. Porpora (1735): edizione critica e commento” (Ph. diss. University of Pa- via-Cremona, 2002); Gaetano Pitarresi, “Una serenata-modello: ‘Gli orti esperidi’ di Pietro Metastasio e Nicola Porpora”, in La serenata tra Seicento e Settecento, ed. -

Baroque EDITIONS RECORDINGS

Baroque Dixit Dominus dates from 1707, and is performed here with ten singers (two to a part) and five-part strings (3.3.2.2.2.1) with organ at the then Roman pitch of A=392. EDITIONS The photograph of the recording shows the arc of singers facing the strings, with the cellos in the centre in front of Francesco Barsanti: Secular Vocal Music the organ and contrabass, and the upper strings to each Recent Researches in the Music of the Baroque Era, 197 side. In the Magnificat, they use the substantial Christian Edited by Michael Talbot Müller organ in Waalse Kerk in Amsterdam, but there is no xxv, 2 + 71pp. $145 photograph to show how the forces are deployed. In their ISBN 978-0-89579-867-1 live performance in St John’s Smith Square last December, the organist was hidden behind the centrally placed organ, Perhaps best known for his recorder sonatas and the and the two groups of SSATB singers radiated outwards recently recorded concerti grossi he published in Edinburgh, on a single plinth from the basses in the middle with the Francesco Barsanti’s secular vocal music fills a fairly modest flutes and oboes in the centre of the orchestra, surrounded volume. Consisting of five Italian cantatas and six French by the 3.3.2.2.1 strings. The trumpets were placed to the airs for solo voice and continuo, a four-voice Italian madrigal treble side of the organ and the timpani to the bass. Even and two catches in English for four equal voices, it provides when miked for a recording, how the singers and players another viewpoint from which to consider one of Handel’s stand in relation to each other is clearly important in this contemporaries. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0259 Notes

P GIACOMO FACCO AND HIS PENSIERI ADRIARMONICI A VERO CONCERTI A 5, OP. 1: II CONCERTOS NOS. 7–12 by Hernan Palma The instrumental concerto probably appeared around 1670, most notably in two centres, Bologna and Rome. The earlier is probably the school associated with the musical cappella at San Petronio, in Bologna, whose most illustrious master is Giuseppe Torelli (1658–1709). His 6 Concerti, Op. 5 (Bologna, 1692), written in four parts, is the earliest collection where an orchestral sound is proposed, clearly differentiated from the chamber sonata; his Concerti musicali, Op. 6 (Augsburg, 1698), require a violin part to be played solo, accompanied exclusively by the continuo, giving birth to the solo concerto; here one also finds some recurring melodies or ritornelli at the beginning and end of movements, and sporadically in between them. In his 12 Concerti grossi con una pastorale, Op. 8 (posthumously published in Bologna in 1709), Torelli’s style reaches full maturity: the concertos are in three movements following the pattern typical of the Italian operatic overture, with ritornelli and episodes clearly differentiated. In Rome the leading figure was Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713), who studied in Bologna for some years in his youth. His collection of 12 Concerti grossi, Op. 6, published posthumously in Amsterdam in 1714 but without doubt of much earlier composition, stands as a milestone in the development of the concerto grosso. Here one finds a four-part texture for two violins, viola and continuo. The string orchestra is divided between a small group, called concertino, and the whole group, called tutti or ripieno. -

Early Opera in Spain and the New World Chad M

World Languages and Cultures Publications World Languages and Cultures 2009 Early Opera in Spain and the New World Chad M. Gasta Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_pubs Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Spanish Literature Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ language_pubs/31. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Early Opera in Spain and the New World Abstract It is not surprising that early modern opera of Spain and its New World colonies has enjoyed little chos larly attention, and there are several reasons for this. First, there are few works from the period to discuss. The genre’s growth in Europe came at a time when the Spanish monarchy was unable and unwilling to provide adequate financial support for its development in the peninsula. This lack of funding, in addition to a general rejection of the genre among the populace, meant that opera’s arrival to Spain’s New World colonies would be delayed as well. Second, with the large number of great comedias to study, the small number of operatic works, their perceived lack of quality, and the emphasis placed solely on their musical value, have put the genre at a disadvantage. -

23 May 2020 – St John's Smith Square Westminster Abbey Grosvenor Chapel St Anne

Beyond the Spanish Golden Age – 9 - 23 May 2020 – St John’s Smith Square Westminster Abbey Grosvenor Chapel St Anne & St Agnes Church – www.lfbm.org.uk – Richard Heason Artistic Director Contents Artistic Director, Richard Heason Saturday 9 May Bach – The 48 / Bach – The 48 4 Sunday 10 May Bach – The 48 / Bach – The 48 5 Monday 11 May When in Rome – when Handel met Corelli 6 © Amy Ryan Wednesday 13 May LFBM Academy 7 focus in the Festival, there is also a wealth of Thursday 14 May The Enlightened Violin: Music for the House of Alba 8 music from the wider Baroque repertoire. Friday 15 May A new addition to the Festival this year Madrid 1700 9 is the creation of our LFBM Academy. Tonos Humanos 10 Margaret Faultless will be leading a brand Saturday 16 May new project to bring the best young baroque The Spanish Guitar from 1500 to 1700 11 musicians together from around the world Juan Hidalgo: Music for the Planet King 12 for three intensive days of workshops and The London Festival of Baroque Music is rehearsals, culminating in our first LFBM Sunday 17 May the much anticipated and celebrated annual Academy concert on 13th May. Chiaroscuro, Lights and Shadows of Spanish Baroque 13 Handel – Ariodante 14 highlight of our Early Music programme at St John’s Smith Square. Once again, we Our goal is always to bring distinctive Monday 18 May look across Europe for our inspiration with programmes of the highest quality to the Duetti da Camera – Handel & his Contemporaries 16 a host of visiting artists and ensembles and Festival. -

Beyond the Spanish Golden Age – 9

Beyond the Spanish Golden Age – 9 - 23 May 2020 – St John’s Smith Square Westminster Abbey Grosvenor Chapel St Anne & St Agnes Church – www.lfbm.org.uk – Richard Heason Artistic Director Contents Artistic Director, Richard Heason Saturday 9 May Bach – The 48 / Bach – The 48 4 Sunday 10 May Bach – The 48 / Bach – The 48 5 Monday 11 May When in Rome – when Handel met Corelli 6 © Amy Ryan Wednesday 13 May LFBM Academy 7 focus in the Festival, there is also a wealth of Thursday 14 May The Enlightened Violin: Music for the House of Alba 8 music from the wider Baroque repertoire. Friday 15 May A new addition to the Festival this year Madrid 1700 9 is the creation of our LFBM Academy. Tonos Humanos 10 Margaret Faultless will be leading a brand Saturday 16 May new project to bring the best young baroque The Spanish Guitar from 1500 to 1700 11 musicians together from around the world Juan Hidalgo: Music for the Planet King 12 for three intensive days of workshops and The London Festival of Baroque Music is rehearsals, culminating in our first LFBM Sunday 17 May the much anticipated and celebrated annual Academy concert on 13th May. Chiaroscuro, Lights and Shadows of Spanish Baroque 13 Handel – Ariodante 14 highlight of our Early Music programme at St John’s Smith Square. Once again, we Our goal is always to bring distinctive Monday 18 May look across Europe for our inspiration with programmes of the highest quality to the Duetti da Camera – Handel & his Contemporaries 16 a host of visiting artists and ensembles and Festival.