RIAA V. the People: Four Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Napster: Winning the Download Race in Europe

Resolution 3.5 July/Aug 04 25/6/04 12:10 PM Page 50 business Napster: winning the download race in Europe A lot of ones and zeros have passed under the digital bridge on the information highway since November 2002, when this column reviewed fledgling legal music download services. Apple has proved there’s money to be made with iTunes music store, street-legal is no longer a novelty, major labels are no longer in the game ... but the Napster name remains. NIGEL JOPSON N RESOLUTION V1.5 Pressplay, co-owned by UK. There’s an all-you-can-download 7-day trial for Universal and Sony, received top marks for user UK residents who register at the Napster.co.uk site. Iexperience. Subscription service Pressplay launched While Apple has gone with individual song sales, with distribution partnerships from Microsoft’s MSN Roxio has stuck to the subscription model and service, Yahoo and Roxio. Roxio provided the CD skewed pricing accordingly. ‘We do regard burning technology. In November 2002, Roxio acquired subscription as the way forward for online music,’ the name and assets of the famed Napster service (which Leanne Sharman told me, ‘why pay £9.90 for 10 was in Chapter 11 protective bankruptcy) for US$5m songs when the same sum gives you unlimited access and 100,000 warrants in Roxio shares. Two months to over half a million tracks?’ earlier, Napster’s sale to Bertelsmann had been blocked Subscription services have come in for heavy — amid concerns the deal had not been done in good criticism from many informed commentators — mostly faith — this after Thomas Middlehoff had invested a multi-computer and iPod owning techno journalists like reputed US$60m of Bertelsmann’s money in Napster. -

You Searched for Busy Mac Torrents

1 / 2 You Searched For Busy : Mac Torrents You can use it forever, at no cost. Premium features can be purchased in the app. Also available on the Mac App Store. Requires macOS 10.12 / iOS 11 / iPadOS .... Apr 20, 2021 — If you search for the best torrent websites for Mac check out the ... Going to a cinema is not always possible with the busy life we all have to lead .... May 18, 2018 — BusyContacts is a contact manager for OS X that lets you create, find ... a powerful tool for filtering contacts, creating saved searches, and even .... We've posted a detailed account of our trouble with PayPal, and the EFF's efforts to ... This has not been ideal, especially of late since I've been so very busy with .... Back. undefined. Skip navigation. Search. Search. Search. Sign in ... Fix most file download errors If you .... 4 days ago — If you wish to download this Linux Mint Cinnamon edition right away, visit this torrent link. ... instilled by other operating systems like Windows and Mac. ... The system user has the option of dismissing the update notification when busy. ... Nemo 5.0 additionally lets a system user perform a content search.. Mar 23, 2020 — Excel For Mac Free Download Demonoid is certainly heading ... Going to a film theater is definitely not generally an option with the busy existence we all possess. ... To download torrénts conveniently we suggest best torrent client for ... You can possibly enter the name of your preferred show to search for it .... Jul 14, 2020 — You'll just need the best Mac torrenting client and a reliable Internet connection. -

Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\7-1\HLS101.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAR-16 12:46 Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms Loren Shokes* In the age of iPods, YouTube, Spotify, social media, and countless numbers of apps, anyone with a computer or smartphone readily has access to millions of hours of music. Despite the ever-increasing ease of delivering music to consumers, the recording industry has fallen victim to “the disease of free.”1 When digital music was first introduced in the late 1990s, indus- try experts and insiders postulated that it would parallel the introduction and eventual mainstream acceptance of the compact disc (CD). When CDs became publicly available in 1982,2 the music industry experienced an un- precedented boost in sales as consumers, en masse, traded in their vinyl records and cassette tapes for sleek new compact discs.3 However, the intro- duction of MP3 players and digital music files had the opposite effect and the recording industry has struggled to monetize and profit from the digital revolution.4 The birth of the file sharing website Napster5 in 1999 was the start of a sharp downhill turn for record labels and artists.6 Rather than pay * J.D. Candidate, Harvard Law School, Class of 2017. 1 See David Goldman, Music’s Lost Decade: Sales Cut in Half, CNN Money (Feb. 3, 2010), available at http://money.cnn.com/2010/02/02/news/companies/napster_ music_industry/. 2 See The Digital Era, Recording History: The History of Recording Technology, available at http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/musicbiz7.php (last visited July 28, 2015). -

The Quality of Recorded Music Since Napster: Evidence Based on The

Digitization and the Music Industry Joel Waldfogel Conference on the Economics of Information and Communication Technologies Paris, October 5-6, 2012 Copyright Protection, Technological Change, and the Quality of New Products: Evidence from Recorded Music since Napster AND And the Bands Played On: Digital Disintermediation and the Quality of New Recorded Music Intro – assuring flow of creative works • Appropriability – may beget creative works – depends on both law and technology • IP rights are monopolies granted to provide incentives for creation – Harms and benefits • Recent technological changes may have altered the balance – First, file sharing makes it harder to appropriate revenue… …and revenue has plunged RIAA Total Value of US Shipments, 1994-2009 16000 14000 12000 10000 total 8000 digital $ millions physical 6000 4000 2000 0 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Ensuing Research • Mostly a kerfuffle about whether file sharing cannibalizes sales • Oberholzer-Gee and Strumpf (2006),Rob and Waldfogel (2006), Blackburn (2004), Zentner (2006), and more • Most believe that file sharing reduces sales • …and this has led to calls for strengthening IP protection My Epiphany • Revenue reduction, interesting for producers, is not the most interesting question • Instead: will flow of new products continue? • We should worry about both consumers and producers Industry view: the sky is falling • IFPI: “Music is an investment-intensive business… Very few sectors have a comparable proportion of sales -

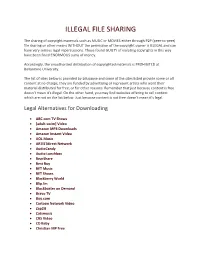

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

Using Green Man Festival As a Case Study

An Investigation to identify how festivals promotional techniques have developed over the years – using Green Man Festival as a case study Victoria Curran BA (hons) Events Management Cardiff Metropolitan University April 2018 i Declaration “I declare that this Dissertation has not already been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. It is the result of my own independent research except where otherwise stated.” Name: Victoria Curran Signed: ii Abstract This research study was carried out in order to explore the different methods of marketing that Green Man Festival utilises, to discover how successful they are, and whether they have changed and developed throughout the years. The study intended to critically review the literature surrounding festivals and festival marketing theories, in order to provide conclusions supported by theory when evaluating the effectiveness of the promotional strategies. It aimed to discover how modern or digital marketing affected Green Man’s promotional techniques, to assess any identified promotional techniques and identify any connections with marketing theory, to investigate how they promote the festival towards their target market, and to finally provide recommendations for futuristic methods of promotion. The dissertation was presented coherently, consisting of five chapters. The first chapter was the introduction, providing a basic insight into the topics involved. The second contains a critical literature review where key themes were identified; the third chapter discussed the methodology used whilst the fourth chapter presents the results that were discovered, providing an analysis and discussion. The final chapter summarises the study, giving recommendations and identifying any limitations of the study. -

AT&T MOBILE MUSIC: Take Control of Your Music

AT&T MOBILE MUSIC: Take Control of Your Music AT&T Mobile Music is the only service that lets you bring subscription music services to your wireless phone, and it offers the largest collection of mobile music content available today from leading music retailers, such as Napster, Yahoo!® Music and eMusic. Designed to deliver “your music, your way,” AT&T Mobile Music puts you in touch with all things music directly from the handset. Available on select handsets, such as the Samsung a717 and a727, AT&T Mobile Music is the ultimate mobile music experience and provides one-click access to a complete suite of music-related content. Music Player Rip music from your CD collection, load it to your phone and select handsets, or play tracks that are accessible from digital music stores. You’ll need a data cable, memory card and stereo headset to fully rock your phone. Shop Music Show your style by downloading ringtones and Answer Tones™. Buy tracks from leading digital music stores, such as Napster, Yahoo! Music and eMusic on select handsets. Streaming Music When you need a change from your music, dozens of commercial-free channels stream the latest tunes in rock, hip-hop, jazz, Latin and other favorites. Add XM Radio or MobiRadio for $8.99 a month. Music Video With an AT&T 3G phone, you can watch your favorite music videos anytime, anywhere. The dancing, the amazing effects, the hot hits — all in the palm of your hand. MusicID “Who sings this?” “What’s this song called?” Know in a flash just by holding up your phone to the music. -

You Are Not Welcome Among Us: Pirates and the State

International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 890–908 1932–8036/20150005 You Are Not Welcome Among Us: Pirates and the State JESSICA L. BEYER University of Washington, USA FENWICK MCKELVEY1 Concordia University, Canada In a historical review focused on digital piracy, we explore the relationship between hacker politics and the state. We distinguish between two core aspects of piracy—the challenge to property rights and the challenge to state power—and argue that digital piracy should be considered more broadly as a challenge to the authority of the state. We trace generations of peer-to-peer networking, showing that digital piracy is a key component in the development of a political platform that advocates for a set of ideals grounded in collaborative culture, nonhierarchical organization, and a reliance on the network. We assert that this politics expresses itself in a philosophy that was formed together with the development of the state-evading forms of communication that perpetuate unmanageable networks. Keywords: pirates, information politics, intellectual property, state networks Introduction Digital piracy is most frequently framed as a challenge to property rights or as theft. This framing is not incorrect, but it overemphasizes intellectual property regimes and, in doing so, underemphasizes the broader political challenge posed by digital pirates. In fact, digital pirates and broader “hacker culture” are part of a political challenge to the state, as well as a challenge to property rights regimes. This challenge is articulated in terms of contributory culture, in contrast to the commodification and enclosures of capitalist culture; as nonhierarchical, in contrast to the strict hierarchies of the modern state; and as faith in the potential of a seemingly uncontrollable communication technology that makes all of this possible, in contrast to a fear of the potential chaos that unsurveilled spaces can bring. -

Peer-To-Peer

Peer-to-peer T-110.7100 Applications and Services in Internet, Fall 2009 Jukka K. Nurminen 1 V1-Filename.ppt / 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen Schedule Tue 15.9.2009 Introduction to P2P (example Content delivery (BitTorrent 12-14 P2P systems, history of P2P, and CoolStreaming) what is P2P) Tue 22.9.2009 Unstructured content search Structured content search 12-14 (Napster, Gnutella, Kazaa) (DHT) Tue 29.9.2009 Energy-efficiency & Mobile P2P 12-14 2 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen Azureus BitTorrent client 3 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen BearShare 4 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen Symbian S60 versions: Symella and SymTorrent 5 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen Skype How skype works: http://arxiv.org/ftp/cs/papers/0412/0412017.pdf 6 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen SETI@home (setiathome.berkeley.edu) • Currently the largest distributed computing effort with over 3 million users • SETI@home is a scientific experiment that uses Internet-connected computers in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). You can participate by running a free program that downloads and analyzes radio telescope data. 7 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen Folding@home (http://folding.stanford.edu/) 8 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. Nurminen PPLive, TVU, … “PPLive is a P2P television network software that famous all over the world. It has the largest number of users, the most extensive coverage in internet.” PPLive • 100 million downloads of its P2P streaming video client • 24 million users per month • access to 900 or so live TV channels • 200 individual advertisers this year alone Source: iResearch, August, 2008 9 2008-10-22 / Jukka K. -

Sponsorship Effects on Music Festival Participants

Copenhagen Business School 2014 MSoc.Sc.Service Management MASTER’S THESIS Sponsorship Effects on Music Festival Participants Victor Guedon David Gramm Kristensen February, 5th, 2014 Supervisor Helle Haurum 111 Pages / 267.755 Characters Abstract While worldwide investments in sole sponsorship fees were expected to reach $53.3 billion in 2013, findings from the academic research on sponsorships’ ability to impact customers’ perception of a sponsor are inconsistent; ranging from positive, small or ambiguous effects to negative or no effects at all. Thus, the objective of the current research was to contribute by researching if participation in a music festival, NorthSide 2013, would influence festival participants’ perception of the main sponsor Royal Beer. To do so, the chosen research design was a pre-post event quasi experimental design with independent samples. It was crucial to have both pre and post event measurements of event participants to investigate a potential change. Moreover, the quasi-experimental strategy was deemed relevant since it features the use of a control group to identify the source of an effect. Identified as one of the reasons for the inconsistent academic findings, the aim was to avoid conscious processing of the respondents by eliciting sponsorships or the two entities together, so that answers collected would account for the effects rather than respondents’ opinions about how this sponsorship affected them. In pursuance of this research several practical steps have been undertaken: a thorough literature review, a face-to-face interview of the Royal Beer brand manager, creation of a beer brand personality scale fitted to the Danish setting, a focus group to translate the brand personality facets and most importantly; the design and data collection of three distinct questionnaires that resulted in a total of 950 valid responses. -

Thehard DATA Summer 2015 A.D

FFREE.REE. TheHARD DATA Summer 2015 A.D. EEDCDC LLASAS VEGASVEGAS BASSCONBASSCON & AAMERICANMERICAN GGABBERFESTABBERFEST REPORTSREPORTS NNOIZEOIZE SUPPRESSORSUPPRESSOR INTERVIEWINTERVIEW TTHEHE VISUALVISUAL ARTART OFOF TRAUMA!TRAUMA! DDARKMATTERARKMATTER 1414 YEARYEAR BASHBASH hhttp://theharddata.comttp://theharddata.com HARDSTYLE & HARDCORE TRACK REVIEWS, EVENT CALENDAR1 & MORE! EDITORIAL Contents Tales of Distro... page 3 Last issue’s feature on Los Angeles Hardcore American Gabberfest 2015 Report... page 4 stirred a lot of feelings, good and bad. Th ere were several reasons for hardcore’s comatose period Basscon Wasteland Report...page 5 which were out of the scene’s control. But two DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 factors stood out to me that were in its control, Noize Suppressor Interview... page 8 “elitism” and “moshing.” Th e Visual Art of Trauma... page 9 Some hardcore afi cionados in the 1990’s Q&A w/ CIK, CAP, YOKE1... page 10 would denounce things as “not hardcore enough,” Darkmatter 14 Years... page 12 “soft ,” etc. Th is sort of elitism was 100% anti- thetical to the rave idea that generated hardcore. Event Calendar... page 15 Hardcore and its sub-genres were born from the PHOTO CREDITS rave. Hardcore was made by combining several Cover, pages 5,8,11,12: Joel Bevacqua music scenes and genres. Unfortunately, a few Pages 4, 14, 15: Austin Jimenez hardcore heads forgot (or didn’t know) they came Page 9: Sid Zuber from a tradition of acceptance and unity. Granted, other scenes disrespected hardcore, but two The THD DISTRO TEAM wrongs don’t make a right. It messes up the scene Distro Co-ordinator: D.Bene for everyone and creativity and fun are the fi rst Arcid - Archon - Brandon Adams - Cap - Colby X. -

Preventing Drug-Related Deaths at Music Festivals: Why the "Rave" Act Should Be Amended to Provide an Exception for Harm Reduction Services

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 93 Issue 3 Comparative and Cross-Border Issues in Article 12 Bankruptcy and Insolvency Law 9-18-2018 Preventing Drug-Related Deaths at Music Festivals: Why the "Rave" Act Should be Amended to Provide an Exception for Harm Reduction Services Robin Mohr Chicago-Kent College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Robin Mohr, Preventing Drug-Related Deaths at Music Festivals: Why the "Rave" Act Should be Amended to Provide an Exception for Harm Reduction Services, 93 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 943 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol93/iss3/12 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PREVENTING DRUG-RELATED DEATHS AT MUSIC FESTIVALS: WHY THE “RAVE” ACT SHOULD BE AMENDED TO PROVIDE AN EXCEPTION FOR HARM REDUCTION SERVICES ROBIN MOHR INTRODUCTION Amid flashing lights and pulsing beats, nearly 100,000 electronic dance music fans attended Electric Zoo on New York’s Randall’s Island in August 2013.1 Unfortunately the party was cut short. Following the deaths of two young fans, the final day of the three-day music festival was can- celed at the request of city authorities.2 In separate incidents, Olivia Ro- tondo, a twenty-year-old University of New Hampshire student, and Jeffrey Russ, a twenty-three-year-old Syracuse University graduate,3 died after collapsing at Electric Zoo with high body temperatures.4 Toxicology results revealed that Ms.