2002. the Case of Midnight Oil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Mainstream Guide to the Moving Image Recordings from the Production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988

Descriptive Level Finding aid LANDER_N001 Collection title Into the Mainstream Guide to the moving image recordings from the production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988 Prepared 2015 by LW and IE, from audition sheets by JW Last updated November 19, 2015 ACCESS Availability of copies Digital viewing copies are available. Further information is available on the 'Ordering Collection Items' web page. Alternatively, contact the Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to view the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on viewing The collection is open for viewing on the AIATSIS premises. AIATSIS holds viewing copies and production materials. Contact AFI Distribution for copies and usage. Contact Ned Lander and Yothu Yindi for usage of production materials. Ned Lander has donated production materials from this film to AIATSIS as a Cultural Gift under the Taxation Incentives for the Arts Scheme. Restrictions on use The collection may only be copied or published with permission from AIATSIS. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1988 Extent: 102 videocassettes (Betacam SP) (approximately 35 hrs.) : sd., col. (Moving Image 10 U-Matic tapes (Kodak EB950) (approximately 10 hrs.) : sd, col. components) 6 Betamax tapes (approximately 6 hrs.) : sd, col. 9 VHS tapes (approximately 9 hrs.) : sd, col. Production history Made as a one hour television documentary, 'Into the Mainstream' follows the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on its journey across America in 1988 with rock groups Midnight Oil and Graffiti Man (featuring John Trudell). Yothu Yindi is famed for drawing on the song-cycles of its Arnhem Land roots to create a mix of traditional Aboriginal music and rock and roll. -

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road Map: Data Assumptions and Modelling

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road Map: Data assumptions and modelling CSIRO Paul Graham, Luke Reedman, Luis Rodriguez, John Raison, Andrew Braid, Victoria Haritos, Thomas Brinsmead, Jenny Hayward, Joely Taylor and Deb O’Connell Centre of Policy Studies Phillip Adams May 2011 Enquiries should be addressed to: Paul Graham Energy Modelling Stream Leader CSIRO Energy Transformed Flagship PO Box 330 Newcastle NSW 2300 Ph: (02) 4960 6061 Fax: (02) 4960 6054 Email: [email protected] Copyright and Disclaimer © 2011 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important Disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. CONTENTS Contents ..................................................................................................................... -

Advertiser of the Month

Holden: Editorial ediToRial Australia has a new Commonwealth Minister for Schools, Early Childhood and Youth, Peter Garrett. The newly titled portfolio splits school education and higher education. Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced on 11 Septem- fasT facTs Quick QuiZ ber that Chris Evans would be her Min- Top ranking Australian university in 1. Did Brontosaurus hang out in ister for Jobs, Skills and Workplace Rela- 2010, measured in terms of research swamps because it was too weak to quality and citation counts, graduate carry its own weight since it couldn’t tions. By 14 September, he’d become employability and teaching quality: chew enough food to fuel itself? Minister for Jobs, Skills, Workplace Australian National University at 20th, 2. Who won this year’s Aurecon Bridge Relations and Tertiary Education. down three places from 17th last year. Building Competition? Garrett and Evans will be assisted by Second ranked: University of Sydney at 3. What weight did the winning bridge Jacinta Collins as Parliamentary Secre- 37th, down from equal 36th last year. carry? Third ranked: University of Melbourne at 4. Can you use a school building fund to tary for Education, Employment and 38th, down from equal 36th last year. pay for running expenses? Workplace Relations. Garrett inherits Fourth: University of Queensland at 43rd, 5. Can you offer a scholarship or bur- responsibility for the as-yet unfi nished down from 41st last year. sary to people other than Australian $16.2 billion Building the Education Fifth: University of New South Wales at citizens or permanent residents? 46, up from equal 47th last year. -

The Ithacan, 1990-10-04

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1990-91 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 10-4-1990 The thI acan, 1990-10-04 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1990-10-04" (1990). The Ithacan, 1990-91. 6. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91/6 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1990-91 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. • ~ I :ii Ithaca. wetlands' construction Fairyland shattered by adminis Midnight Oil gives held Up tration indecisiveness anticlimactic performance .•• page 6 ... page 7 ... page 9 ,, ... ,,1,'-•y•'• ,,1. :CJ<,·')• ..... The ITHACAN The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Vol. 58, No. 6 October 4, 1990 24 pages Free Arrests. conti:n-ue despite warning lcm." 'crackdown' on parties on South neighborhoods. 75 student arrests over--past three weeks Dave Maley, Manager of Public Hill. McEwen said that he needs at "I expect students to think of this By Joe Porletto Holt, head of the IC office of cam Information for IC, said that when least one additional officer, but there area as their home," McEwen said. The weekend of Sept. 28 resulted pus"' safety, addressed the party students are off-campus they must isn't room in the city budget for it McEwen said that studcn ts wouldn't in 26 arrests of college students on proolem. -

Midnight Oil in the Valley Mp3, Flac, Wma

Midnight Oil In The Valley mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: In The Valley Country: France Released: 1993 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1770 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1593 mb WMA version RAR size: 1999 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 645 Other Formats: TTA WMA TTA MP4 MMF AUD VQF Tracklist 1 In The Valley 4:40 2 Ships Of Freedom 3:14 3 My Country (Live) 4:51 4 Blue Sky Mine (Live) 4:23 Credits Engineer, Mixed By – Mike Walter, Nick Launay Producer – Midnight Oil (tracks: 1, 2), Nick Launay (tracks: 1, 2) Written-By – Jim Moginie (tracks: 1), Midnight Oil (tracks: 4), Peter Garrett (tracks: 1), Rob Hirst (tracks: 1, 2, 3) Notes Taken from the album "Earth And Sun And Moon" Tracks 3 & 4 recorded live at Ronnie Scotts, London, June 23rd 1993. Tracks 1 & 4 used by kind permission of the BBC. ℗ & © Midnight Oil 1993 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Label Code): 5099765978025 Other (Label Code): LC 0162 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 659906 2 Midnight Oil In The Valley (CD, Maxi) Columbia 659906 2 Australia 1993 659849 6 Midnight Oil In The Valley (12") Columbia 659849 6 Europe 1993 XPCD 334 Midnight Oil In The Valley (CD, Single, Promo) Columbia XPCD 334 UK 1993 659849 7 Midnight Oil In The Valley (7", Single) Columbia 659849 7 Europe 1993 659849 2 Midnight Oil In The Valley (CD, Maxi) Columbia 659849 2 UK & Europe 1993 Related Music albums to In The Valley by Midnight Oil Midnight Oil - Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil - Midnight Oil Midnight Oil - Tracks From The Forthcoming Album "Breathe" Midnight Oil - Place Without A Postcard Midnight Oil - Truganini Midnight Oil - Les Indispensables De Midnight Oil Midnight Oil - 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 Midnight Oil - Earth And Sun And Moon Midnight Oil - Sometimes London After Midnight - Selected Scenes After Midnight. -

COMM∆ND SMEDI∆ Inc. TORONTO

COMM∆ND S MEDI∆ iNc. TORONTO email > [email protected] telephone > +1 (604) 688-4217 w∆rnelivesey - production discography 2021 full length lp - production, mixing and engineering [except where noted] •recent work midnight oil - The Makarrata Project - new LP for release 2021 andee - lost in rewind (single) kandle - just to bring you back (single) [co-write, production, mixing] kelly heeley - EP [mixing] •less recent work midnight oil - diesel and dust - blue sky mining - redneck wonderland - capriconia - 20,000watts r.s.l the the - infected - mindbomb matthew good band - underdogs - beautiful midnight - audio of being matthew good - lights of endangered species - avalanche - white light rock n’ roll review - in a coma - chaotic neutral - i miss new wave (beautiful midnight revisited EP) - something like a storm - moving walls kim churchill - silence/win [co-songwriting/ production/ engineering/ mixing] - into the steel [string arrangements / co-production] - weight falls [co-songwriting, production 3 songs] xavier rudd - koonyum sun [mixing] email > [email protected] telephone > +1 (604) 688-4217 1 w∆rnelivesey - discography continued… julian cope - saint julian house of love - babe rainbow [co-songwriting / production] deacon blue - when the world knows your name [production / engineering] sinhead o’conner / the the - kingdom of rain (track from collaborations lp) paul young - other voices [production] jesus jones - perverse 54-40 - yes to everything - goodbye flatland [mixing] - northern soul [mixing] mark hollis - mark hollis [co-songwriting] -

“Life on Earth Is at Immediate Risk and Only Implementing the Earth Repair Charter Can Save It”

Join with these Earth Repair Charter endorsers and like and share this Now Age global solution strategy towards helping make the whole world great for everyone. Share earthrepair.net “Life on Earth is at immediate risk and only implementing the Earth Repair Charter can save it”. Richard Jones, Former MLC, Independent, NSW Parliament, Australia “I consider that the Earth Repair Charter is self-evident as an achievable Global Solution Strategy. I urge every national government to adopt it as the priority within each country”. Joanna Macy, PhD , Professor, Teacher, Author, Institute for Deep Ecology, USA “I was thrilled to receive your Earth Repair Charter and all my best wishes are behind it”. David Suzuki, David Suzuki Foundation “The Earth Repair Charter is helping us to be enlightened in our relationship with the Earth and compassionate to all beings”. H.H. The Dalai Lama “The Earth Repair Charter is the way to rescue the future from further ignorance and environmental degradation. Please promote the Charter to help create a safer, healthier and happier world”. Geoffrey BW Little JP, Australia’s Famous, International Smiling Policeman “I am pleased to say that the Earth Repair Charter represents the best possible path for everyone to consider. Best wishes, Good luck”. Peter Garrett, Midnight Oil and Past President of ACF “The Earth Repair Charter has the capacity to galvanise action against the neglect by governments of that which should be most treasured - peace, justice and a healthy planet. I endorse it with great enthusiasm”. Former Senator Lyn Allison, Australian Democrats “The Earth Repair Charter is, in our opinion, a document that can greatly contribute to improving the quality of life on this planet”. -

![[Download] Midnight 13](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2541/download-midnight-13-532541.webp)

[Download] Midnight 13

[PDF-a03]Midnight 13 Midnight 13 Midnight Oil - Wikipedia Dexys Midnight Runners - Wikipedia The Midnight Website Sun, 28 Oct 2018 04:02:00 GMT Midnight Oil - Wikipedia Midnight Oil (known informally as "The Oils") are an Australian rock band composed of Peter Garrett (vocals, harmonica), Rob Hirst (drums), Jim Moginie (guitar, keyboard), Martin Rotsey (guitar) and Bones Hillman (bass guitar). The group was formed in Sydney in 1972 by Hirst, Moginie and original bassist Andrew James as Farm: they enlisted Garrett the following year, changed their name in 1976 ... Dexys Midnight Runners - Wikipedia Dexys Midnight Runners (currently officially Dexys, their former nickname, styled without an apostrophe) are an English pop band with soul influences, who achieved their major success in the early to mid-1980s. They are best known in the UK for their songs "Come On Eileen" and "Geno", both of which peaked at No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart, as well as six other top-20 singles. [Download] Midnight 13 The Midnight Website Midnight were formed in 2003, inspired by the magical sound of Blackmore's Night.The choice to be called "Midnight" is not accidental: "midnight" is a metaphor not only of a past time, but also a "mysterious elsewhere" the magic hour of the night for excellence, where fairies and elves dance in the woods, the wizards prepare their spells and the witches gather under a large walnut tree. pdf Download Midnight Club 2 on Steam The world's most notorious drivers meet each night on the streets of LA, Paris, and Tokyo. Choose from a collection of performance-enhanced cars or bikes and compete head-to-head to make a name for yourself. -

City of Wagga Wagga Annual Report 2015-16 2 City of Wagga Wagga Annual Report 2015-16 Statement of Commitment to Aboriginal Australians

CITY OF WAGGA WAGGA ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 2 CITY OF WAGGA WAGGA ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 STATEMENT OF COMMITMENT TO ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS The City of Wagga Wagga acknowledges and respects Council is committed to developing programs to improve that Aboriginal people were the first people of this the wellbeing of all City of Wagga Wagga residents as land and the Wiradjuri people were the first regional well as facilitating reconciliation between Aboriginal and custodians of the Wagga Wagga Local Government Area. non-Aboriginal people. This recognition includes acceptance of the rights and Council recognises that social justice and reconciliation responsibilities of Aboriginal people to participate in are fundamental to achieving positive changes. Council decision making. will continue to actively encourage Aboriginal and non- Council acknowledges the shared responsibility of all Aboriginal people to work together for a just, harmonious Australians to respect and encourage the development of and progressive society. an awareness and appreciation of each other’s origin. In Council recognises that the richness of Aboriginal cultures so doing, Council recognises and respects the heritage, and values in promoting social diversity within the culture, sacred sites and special places of Aboriginal community. people. CITY OF WAGGA WAGGA ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 3 Sustainable Future Framework Our approach to Integrated Planning and Reporting State and Regional Plans Community Strategic Plan Ruby & Oliver Long term plan that clearly defines what we want as a community. 1LEVEL Council Strategies Resourcing Providing directions Strategies LEVEL 2 Internal instruments (how) we deliver: social economic environmental civic leadership Long Term Financial Plan Asset Management Plan Business Planning Process Workforce Plan Divisional process informing resourcing Section 94 and delivery Developer contribution Community Engagement Delivery Program 4 years Identifies the elected Council’s Policies, operating priorities for their term of office. -

Instrumental Newsletter

EDITION #20 – September 2008 SPECIAL "SHADOZ" ISSUE!! "Shadoz 2008" marked our 6th anniversary, as well as the 50th anniversary of Cliff and The Shadows. Yet another new venue, and, from all reports the best yet. On a sad note, we recently lost one of our Shadoz friends, Don Hill. Don played drums for Harry's Webb and The Vikings last year, and was one of the 'stalwarts' of Shadoz in recent times. R.I.P. Don. TONY KIEK (Keyboards) and GEORGE LEWIS (Guitar) were fresh from a tour of the UK, where they appeared at a number of Shadows clubs. They were gracious enough to help out by filling the 'dreaded' opening spot. Their set was a wonderful introduction to the day, and they featured some great sounds with WONDERFUL LAND / FANDANGO (with WALTZING MATILDA intro) / DANCES WITH WOLVES / THING-ME-JIG / RODRIGO'S CONCERTO / GOING HOME (THEME FROM 'LOCAL HERO') / THE SAVAGE / SPRING IS NEARLY HERE Whilst Tony and George travelled down from Sydney, no less a feat were the next band, who have travelled from overseas – Phillip Island! - ROB WATSON (Bass) was formerly with Melbourne group "The Avengers", TONY MERCER (Lead Guitar) also played with various Melbourne groups before "retiring" to the island and forming "SHAZAM", MIKE McCABE (Rhythm) worked in England in the 60's with "Hardtack", MARTY SAUNDERS (Drums) played with the popular showband "Out To Lunch" amongst others, and JEFF CULLEN (Lead vocals and rhythm guitar) sang with The Aztecs in Sydney before Billy Thorpe, then with The Rat Finks. A nice mix of Shads and non-Shads numbers included ADVENTURES IN PARADISE / MAN OF MYSTERY / ATLANTIS / THE CRUEL SEA / THE RISE AND FALL OF FLINGEL BUNT / GENIE WITH THE LIGHT BROWN LAMP / IT'S A MAN'S WORLD / THE SAVAGE / CINCINNATTI FIREBALL (voc) / LOVE POTION NO.9 (voc) / THE WANDERER (voc) / THE STRANGER / WALK DON'T RUN One of the joys of "Shadoz" is the ability to welcome newcomers to our shindig. -

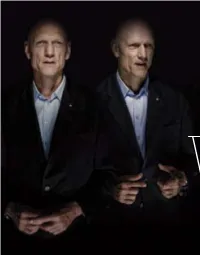

14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 He Easy – and Dare I Say It Tempting – Story to Write Translating About Peter Garrett Starts Something Like This

WOLVES 14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 he easy – and dare i say it tempting – story to write Translating about Peter Garrett starts something like this. “Peter Garrett songs on the was once the bold and radical voice of two generations of Australians and at a crucial juncture in his life decided to pop stage into forsake his principles for political power. Or for political action on the irrelevance. Take your pick.” political stage We all know this story. It’s been doing the rounds for five years now, ever since Garrett agreed to throw in his lot with Labor and para- was never Tchute safely into the Sydney seat of Kingsford Smith. It’s the story, in effect, going to be of Faust, God’s favoured mortal in Goethe’s epic poem, who made his com- easy, but to his pact with the Devil – in this case the Australian Labor Party – so that he might gain ultimate influence on earth. The price, of course – his service to critics, Peter the Devil in the afterlife. Garrett has We’ve read and heard variations on this Faustian theme in newspapers, failed more across dinner tables, in online chat rooms, up-country, outback – everyone, it seems, has had a view on Australia’s federal Minister for the Environment, spectacularly Arts and Heritage, not to mention another song lyric to throw at him for than they ever his alleged hollow pretence. imagined. He’s all “power no passion”, he’s living “on his knees”, he’s “lost his voice”, he’s a “shadow” of the man he once was, he’s “seven feet of pure liability”, David Leser he’s a “galah”, “a warbling twit”, “a dead fish”, and this is his “year of living talks to the hypocritically”. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here..