Chinn, Philip C. a Multiethnic Curriculum for Special Educat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the Fifteenth Workshop on Graph-Based Methods for Natural Language Processing (Textgraphs-15), Pages 1–9 June 11, 2021

NAACL-HLT 2021 Graph-Based Methods for Natural Language Processing Proceedings of the Fifteenth Workshop June 11, 2021 ©2021 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-954085-38-1 ii Introduction Welcome to TextGraphs, the Workshop on Graph-Based Methods for Natural Language Processing. The fifteenth edition of our workshop is being organized online on June 11, 2021, in conjunction with the 2021 Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL-2021). The workshops in the TextGraphs series have published and promoted the synergy between the field of Graph Theory (GT) and Natural Language Processing (NLP). The mix between the two started small, with graph theoretical frameworks providing efficient and elegant solutions for NLP applications. Graph- based solutions initially focused on single-document part-of-speech tagging, word sense disambiguation, and semantic role labeling, and became progressively larger to include ontology learning and information extraction from large text collections. Nowadays, graph-based solutions also target on Web-scale applications such as information propagation in social networks, rumor proliferation, e-reputation, multiple entity detection, language dynamics learning, and future events prediction, to name a few. The target audience comprises researchers working on problems related to either Graph Theory or graph- based algorithms applied to Natural Language Processing, Social Media, and the Semantic Web. This year, we received 22 submissions and accepted 17 of them for oral presentation (12 long papers and 5 short papers). -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research And

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] H & H - Deep Hackberry Ramblers - Crowley Waltz Hackberry Ramblers - Tickle Her Hackett, Bobby - New Orleans Hackett, Buddy - Advice For young Lovers Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Laundry (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Rock and Egg Roll Hackett, Buddy - Diet Hackett, Buddy - It Came From Outer Space Hackett, Buddy - My Mixed Up Youth Hackett, Buddy - Old Army Routine Hackett, Buddy - Original Chinese Waiter Hackett, Buddy - Pennsylvania 6-5000 (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Songs My Mother Used to Sing To Who 1993 Haddaway - Life (Everybody Needs Somebody To Love) 1993 Haddaway - What Is Love Hadley, Red - Brother That's All (Meteor 5017) Hadley, Red - Ring Out Those Bells (Meteor 5017) 1979 Hagar, Sammy - (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Eagle's Fly 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Give To Live 1984 Hagar, Sammy - I Can't Drive 55 1982 Hagar, Sammy - I'll Fall In Love Again 1978 Hagar, Sammy - I've Done Everything For You 1978 1983 Hagar, Sammy - Never Give Up 1982 Hagar, Sammy - Piece Of My Heart 1979 Hagar, Sammy - Plain Jane 1984 Hagar, Sammy - Two Sides -

Wikigraphs: a Wikipedia Text-Knowledge Graph Paired

WikiGraphs: A Wikipedia Text - Knowledge Graph Paired Dataset Luyu Wang* and Yujia Li* and Ozlem Aslan and Oriol Vinyals *Equal contribution DeepMind, London, UK {luyuwang,yujiali,ozlema,vinyals}@google.com Freebase Paul Hewson Abstract WikiText-103 Bono type.object.name Where the streets key/wikipedia.en “Where the Streets Have have no name We present a new dataset of Wikipedia articles No Name” is a song by ns/m.01vswwx Irish rock band U2. It is the ns/m.02h40lc people.person.date of birth each paired with a knowledge graph, to facili- opening track from their key/wikipedia.en 1987 album The Joshua ns/music.composition.language music.composer.compositions Tree and was released as tate the research in conditional text generation, 1960-05-10 the album’s third single in ns/m.06t2j0 August 1987. The song ’s ns/music.composition.form graph generation and graph representation 1961-08-08 hook is a repeating guitar ns/m.074ft arpeggio using a delay music.composer.compositions people.person.date of birth learning. Existing graph-text paired datasets effect, played during the key/wikipedia.en song’s introduction and ns/m.01vswx5 again at the end. Lead David Howell typically contain small graphs and short text Evans, better vocalist Bono wrote... Song key/wikipedia.en known by his ns/common.topic.description stage name The (1 or few sentences), thus limiting the capabil- Edge, is a people.person.height meters The Edge British-born Irish musician, ities of the models that can be learned on the songwriter... 1.77m data. -

Cash Box NY Telex: 666123 Tists (Page 7)

UA-LA958-I Featuring ^ “Days Gone Down On United Artists Records in .C 1979 LIBERTY UNITED RECORDS. INC . LOS ANGELES CALIFORNIA 90028 UNITED ARTISTS RECORDS IS A TRADING NAM.F VOLUME XLI — NUMBER 3 — JUNE 2, 1979 FHE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY C4SH GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher ? 5 MEL ALBERT “An Apple A Day Vice President and General Manager EDITORML CHUCK MEYER value. billboard. Director of Marketing Records are your best entertainment DAVE FULTON With near unanimous agreement that the Considering that consumers are looking for the In Chief Editor aforementioned maxim is true, it is time to let others most for their money, the time is right to let them J.B. CARMICLE realize this secret. know the investment value of music. With minimal General Manager. East Coast And the great hook to this is that it can be done care, a consumer can spend $4-6and haveawork of JIM SHARP Director, Nashville without a costly advertising campaign which also re- art for a lifetime. East Coast Editorial quires executives from various labels to agree to a This simple program needs to be coordinated KEN TERRY East Coast Editor CHARLES PAIKERT budget and a creative approach. Quite simply, a through the RIAA or another industry organization LEO SACKS AARON FUCHS series of phone calls and verbal agreements are all that will take the initiative to promote the concept to West Coast Editorial that is needed. the manufacturers. In a matter of days, the plan ALAN SUTTON. West Coast Editor JOEY BERLIN — RAY TERRACE Whenever a manufacturer advertises his albums, could be instituted. -

Parishioners Buy Home for Loyola C^Ent

Colorado's Largest Newspaper; Total Press Run, All Editions, Far Above SOOfiOO; Denver Catholic Register, 28^92 PARISHIONERS BUY HOME FOR LOYOLA C ^ E N T Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic J^ress Society, Ino., 1948— Permission to Reproduce, Except PRIEST WHO STUDIED IN ST. THOMAS’ on Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Some Money Donated; 1ST CATHOLIC CHAPLAIN IN PANDO DENVER CATHaiC Committee 1$ Raising A priest who made a portion of training center in which men are the Rev. John Cavanagh of the his'studies in St. Thomas’ semi being taught mountain fighting, RegUter staff. nary, Denver, has been named the including skiing, snow-shoeing, and Skeptical About Camp first Catholic chaplain of Camp all the arts of the Alpinist. Funds for Remainder Hale in Pando, near Leadville. He Father Bracken is a native of Concerning Camp Hale, the Rev. is Chaplain Thomas Bracken, a St. Louis, Mo. After making col Robert A. Banigan, assistant pas tor o f . Annunciation parish in captain, who has been on active lege and philosophical studies in duty with the armed forces since St. Thomas’ seminary, he went to Leadville, this week wrote: F ^ G IS T E R Nine-Room House Will Enable Charily Sisters Last spring yhen the rumor March 3, 1941. the North American college in The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We spread that an army camp was be Camp Hale is a specialists’ Rome. He was ordained in the Have Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller ing considered at Pando, most of To Live Near Schooi; House-Warming Eternal City by the late Arch Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. -

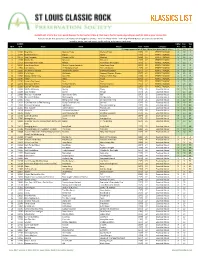

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

1970S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1970 She Belongs To Me Rick Nelson Jan 1970 Winter World Of Love Engelbert Humperdinck Jan 1970 Without Love Tom Jones Jan 1970 Arizona Mark Lindsay Jan 1970 Hey There Lonely Girl Eddie Holman Jan 1970 She Came In Through The Bathroom Joe Cocker Jan 1970 Thank You (Falettinme..) Sly & The Family Stone Jan 1970 No Time Guess Who Jan 1970 Walk A Mile In My Shoes Joe South Jan 1970 Baby, Take Me In Your Arms Jefferson Jan 1970 Walkin' In The Rain Jay & The Americans Jan 1970 Let A Man Come In & Do The Popcorn James Brown Jan 1970 Let's Work Together Wilbert Harrison Jan 1970 Psychedelic Shack Temptations Jan 1970 Fancy Bobbie Gentry Jan 1970 Honey Come Back Glen Campbell Jan 1970 Rainy Night In Georgia Brook Benton Jan 1970 Thrill Is Gone BB King Feb 1970 Didn't I Blow Your Mind Delfonics Feb 1970 Evil Ways Santana Feb 1970 Give Me Just A Little Time Chairman Of The Board Feb 1970 He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother Hollies Feb 1970 Ma Belle Amie Tee Set Feb 1970 Monster/Suicide/America Steppenwolf Feb 1970 Oh Me Oh My Lulu Feb 1970 Travelin' Band Creedence Clearwater Revival Feb 1970 One Tin Soldier Coven Feb 1970 Who'll Stop The Rain Creedence Clearwater Revival Feb 1970 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Feb 1970 The Rapper Jaggerz Feb 1970 If I Were A Carpenter Johnny Cash Feb 1970 Street People Jennifer Tomkins Feb 1970 Kentucky Rain Elvis Presley Feb 1970 Never Had A Dream Come True Stevie Wonder Feb 1970 Call Me Aretha Franklin Feb 1970 Do The Funky Chicken Rufus Thomas Feb 1970 Easy Come, Easy Go Bobby Sherman Feb 1970 Gotta Hold On To This Feeling Jr. -

Intimate Emptiness: the Flint Hills Wind Turbine Controversy

INTIMATE EMPTINESS: THE FLINT HILLS WIND TURBINE CONTROVERSY BY Howard Graham Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. _________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Norm Yetman Committee Members _________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester _________________________ Dr. D. Anthony Tyeeme Clark Date Defended: July 2, 2008 The Thesis Committee for Howard Graham certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: INTIMATE EMPTINESS: THE FLINT HILLS WIND TURBINE CONTROVERSY _________________________ Dr. Norm Yetman Date Approved: July 2, 2008 ii ABSTRACT Howard Graham, Master of Arts American Studies, July 2008 University of Kansas This study examines the political and social controversy surrounding the proposed introduction of industrial scale wind turbines, roughly, those over 120 feet, in the Flint Hills region of Kansas. The study is primarily concerned with the proposed introduction of wind turbines in Wabaunsee County, Kansas and examines the County’s consideration of wind turbine projects between 2002 and 2004. The controversy is contextualized within the social, political, geographical, geologic, and cultural history of the Flint Hills region. The study also examines how these historical factors inform the way people look at and understand both the prairie and wind turbines. Much of the information is gathered from Wabaunsee County Commission and Planning Commission meeting minutes, as well as transcripts of these meetings. The paper concludes by advocating for the continued absence of industrial scale wind turbines in the Flint Hills. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee, professors Norm Yetman, Cheryl Lester, and D. -

Membedah Classic Rock Interpretasi, Komentar, Pengalaman,

Membedah Classic Rock Interpretasi, komentar, pengalaman, ... Budi Rahardjo Membedah Classic Rock.....................................................................1 In the beginning ….............................................................................13 Psychedelic.....................................................................................14 Pada mulanya ….............................................................................16 Mencari Kaset / CD / Lagu Classic Rock....................................22 Camel..................................................................................................26 Stationary Travel...........................................................................27 Saran Lagu.....................................................................................29 Dream Theater..................................................................................30 Images And Words.......................................................................30 Octavarium.....................................................................................31 Saran Lagu......................................................................................31 ELP......................................................................................................32 Genesis................................................................................................34 Awal terbentuknya........................................................................35 Gabriel vs Collins...........................................................................36 -

09 14 2010 Sect 1 (Pdf)

Retired race horses get “Second Start at Cloud” By Donna Sullivan, industry a service by tak- how to run fast and turn Editor ing these horses and it left.” So re-training them As horse racing enthu- gives our students a for other uses is the first siasts watch their favorite chance to explore the dis- step in the process, with steeds circle the track, it ciplines within the horse the eventual goal being likely never crosses their industry, such as racing, horses that are suitable for minds what becomes of Western riding, English adoption. the equine athletes once riding, jumping and cattle Six horses arrived on their careers are over. handling.” Their agree- the campus two years ago, Founded in 1982, the ment states that TRF will ranging in age from 5-11 Thoroughbred Retirement pay for feed for the years old. “An older horse Foundation (TRF) strives horses as well as basic will sometimes come to protect retired racehors- care, while the training re- around faster than a es from neglect, abuse and sponsibilities and equip- younger one, depending slaughter. They found a ment costs fall to the col- on their dispositions,” partner in a relatively new lege. Zenger-Beneda explained. program at Cloud County Bill McGuire, Depart- At first only advanced stu- Community College in ment Chair of Agriculture dents were allowed to Concordia called The Sec- at CCCC, started the work with them. ond Start at Cloud. Equine program, known as She taught the Intro to Marshal Kohlman, Salina, spends time with King, a thoroughbred obtained through According to Nancy The Horse Play Series, Horsemanship class last the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation. -

Presented to the Johnson County Board of Park and Recreation

1 Presented to The Johnson County Board of Park and Recreation Commissioners October 2008 Landscape Architects Bowman Bowman Novick Inc. Environmental Consultant Burns and McDonnell Communications & Public Outreach Consultant Jane Mobley Associates 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Process ........................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Task 1: Existing Site Inventory and Analysis .............................................................................................................. 6 Task 2: Public Workshop #1 ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Task 3: Preliminary Design ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Task 4: Public Workshop #2 ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Task 5: Final Report ................................................................................................................................................. -

―Selected Stories by O. Henry‖

―Selected Stories by O. Henry‖ Направление: 45.03.02 Лингвистика Учебный план: перевод и переводоведение (английский и второй иностранный), (очное, 2014) Дисциплина: Практический курс первого иностранного языка (английский язык), (бакалавриат, 1 курс, очное обучение) Количество часов: 90 ч. (в том числе: практические занятия –36, самостоятельная работа – 54); форма контроля: зачет. Направление: 45.03.02 Лингвистика Учебный план: перевод и переводоведение (немецкий и второй иностранные языки), (очное, 2013) Дисциплина: Практический курс второго иностранного языка (английский язык), (бакалавриат, 2 курс, очное обучение) Количество часов: 72 ч. (в том числе: практические занятия – 36, самостоятельная работа –36); форма контроля: тестирование. Направление: 031900.62 Международные отношения Учебный план: международные отношения (не предусмотрено) очное, бакалавр международных отношений со знанием иностранного языка, 2014 Дисциплина: Иностранный язык (бакалавриат, 1 курс, очное обучение) Количество часов: 72 ч. (в том числе: практические занятия – 36, самостоятельная работа – 36), форма контроля: тестирование (1 семестр). Аннотация: Данный электронный образовательный ресурс предназначен для организации практических занятий и самостоятельной работы студентов по освоению Практического курса первого иностранного языка (английский язык) и Иностранного языка (английский язык) на 1 курсе, Практического курса второго иностранного языка (английский язык) на 2 курсе, аспект «Домашнее чтение». При составлении ресурса были учтены требования к содержанию данных курсов для студентов лингвистических специальностей. Курс включает в себя содержание текстов для домашнего чтения, материал для практических занятий и самостоятельной работы студентов, глоссарий, список литературы и сетевых источников, а также контрольный блок по каждой теме. Обеспечено ЭК: 1. Biography of O. Henry 2. The Green Door 3. The Enchanted Profile 4. The Indian Summer of Dry Valley Johnson 5. A Retrieved Reformation 6. After Twenty Years 7.