Report of the Independent Investigator Into Allegations of Labor And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Construction 2025 Industrial Strategy.Pdf

Industrial Strategy: government and industry in partnership Construction 2025 July 2013 Cover photo credit: John McAslan & Partners and Hufton & Crow CONTENTS | CONSTRUCTION 2025 1 Contents Executive summary 3 Foreword 16 Our vision for 2025 18 Our joint ambition 19 Our joint commitments 20 Chapter 1: Strategic Context 22 Chapter 2: Strategic Priorities 31 Chapter 3: Drivers of Change 39 Chapter 4: Leadership 63 Annex A: Construction Leadership Council membership 64 Annex B: Action Plan 65 Acknowledgement 72 A Note on Devolution 73 Credit: David Churchill EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | CONSTRUCTION 2025 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | CONSTRUCTION 2025 3 Executive summary Construction is a sector where Britain has a strong competitive edge. We have world-class expertise in architecture, design and engineering, and British companies are leading the way in sustainable construction solutions. It is also a sector with considerable growth opportunities, with the global construction market forecast to grow by over 70% by 2025. Changes in the international economy are creating new opportunities for Britain. To help boost the economic recovery, Government is doing all it can to help British businesses grow and have the aspiration, confidence and drive to compete in the global race. This includes reforming the planning system, ensuring funding is available for key infrastructure projects and supporting the housing market through key initiatives such as the Help-to-Buy Equity Loan Scheme and the Funding for Lending Scheme. The Government wants to work with industry to ensure British companies are well-placed to take advantage of these opportunities. As part of our Industrial Strategy policy, the Government is building long-term partnerships with sectors that can deliver significant growth. -

Construct Zero: the Performance Framework

Performance Framework Version 1 Foreword As Co-Chair of the Construction Leadership The Prime Minister has been clear on the Council, I’m delighted to welcome you to importance of the built environment sector in ‘Construct Zero: The Performance Framework. meeting his target for the UK to reduce its carbon The Prime Minister has set out the global emissions by 78% compared to 1900 levels by importance of climate change, and the need for 2035. Put simply, the built environment accounts for collective action from firms and individuals 43% of UK emissions, without its contribution- we across the UK, to address the challenge of will not meet this target, and support the creation of climate change and achieve net zero carbon 250,000 green jobs. emissions in the UK by 2050. Therefore, I’m delighted the Construction Never before has there been such a strong Leadership Council (CLC) is leading the sector’s collective desire across the political spectrum, response to this challenge, through the Construct society, and businesses for us to step up to the Zero change programme. Building on the success challenge. We all have a responsibility to step of the sector’s collaborations during COVID, the up and take action now to protect the next CLC has engaged the industry to develop the generation, our children’s children. It is our Performance Framework, which sets out how the duty to do so, as citizens, parents, and leaders sector will commit to, and measure it’s progress to enable and provide a better world for our towards, Net Zero. -

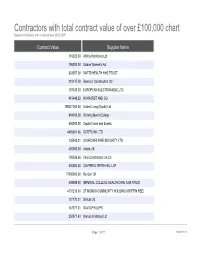

Contractors with Total Contract Value of Over £100,000 Chart Based on Contracts with a Value of Over 5000 GBP

Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP Contract Value Supplier Name 116325.00 Affinity Workforce Ltd 796000.00 Solace Women's Aid 323557.00 BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 210147.00 Boxmoor Construction Ltd 107420.30 EUROPEAN ELECTRONIQUE LTD 415448.22 HAYHURST AND CO 198221000.00 United Living (South) Ltd 894000.00 Working Men's College 450000.00 Capita Travel and Events 4405561.66 CATERLINK LTD 135545.21 CHURCHES FIRE SECURITY LTD 400000.00 Artelia UK 105036.66 Vinci Construction Uk Ltd 500000.00 CAMPBELL REITH HILL LLP 17000000.00 Re-Gen UK 408098.00 IMPERIAL COLLEGE HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 4707213.00 ST MUNGO COMMUNITY HOUSING (GRIFFIN HSE) 131176.21 Softcat Ltd 147371.31 DAVID PHILLIPS 250971.43 Marcus & Marcus Ltd Page 1 of 22 10/02/2021 Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP 136044.00 CENTRAL & CECIL 198667.55 GODWIN & CROWNDALE TMC LTD 288142.90 PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS 494918.96 APEX HOUSING SOLUTIONS 425000.00 Rick Mather Architects LLP 148855.40 Alderwood LLA Ltd - Irchester 2 821312.26 Falcon Structural Repairs 1169203.00 Ark Build PLC 103675.37 MANOR HOSTELS (LONDON) LTD 319608347.72 VEOLIA ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES (UK) PLC 299532.76 CASTLEHAVEN COMMUNITY ASSOC. 207757.50 PERSONALISATION SUPPORT IN CAMDEN 12000000.00 AD Construction Group 678874.77 St Johns Wood - Lifestyle Care (2011) PLC 424893.63 INSIGHT DIRECT (UK) LTD 150366.19 HOLLY LODGE ESTATE COMMITTEE 114136.63 SPECIALIST COMPUTER CENTRES 943735.13 Mihomecare 4800000.00 Turner & Townsend Project Management Ltd 140000000.00 Volkerhighways 233048.00 KPMG 1150000.00 LONDON DIOCESAN BOARD FOR SCHOOLS Page 2 of 22 10/02/2021 Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP 302480.00 DAISY DATA CENTRE SOLUTIONS LTD 30000000.00 Eurovia Infrastructure 140126.15 DAWSONRENTALS BUS & COACH LTD 261847.08 ST MARTIN OF TOURS HOUSING ASSOC. -

Future Imperfect, Contemporary Art Practices and Cultural Institutions In

Visual Culture in the Middle East 3 FUTURE IMPERFECT Contemporary Art Practices and Cultural Institutions in the Middle East Edited by Anthony Downey Published by Sternberg Press ISBN 978 3 95679 246 5 FUTURE IMPERFECT Contemporary Art Practices and Cultural Institutions in the Middle East Edited by Anthony Downey www.ibraaz.org Ibraaz is the research and publishing initiative of the Kamel Lazaar Foundation 11 FOREWORD Kamel Lazaar 14 INTRODUCTION: FUTURE IMPERFECT Critical Propositions and Institutional Realities in the Middle East Anthony Downey PART I REGIONAL CONTEXTS Fragmentary Networks and Historical Antagonisms 48 FILLING THE GAPS Arts Infrastructures and Institutions in Post-Dictatorship Libya Hadia Gana 61 ARTISTS AND INSTITUTION BUILDING IN SITU The Case of Morocco Lea Morin 74 IN THE ABSENCE OF INSTITUTIONS Contemporary Cultural Practices in Algeria Yasmine Zidane 85 SOCIAL PRACTICES AND INSTITUTIONAL REALIGNMENTS IN TUNISIA SINCE 2010 Wafa Gabsi 98 MAKING STORIES VISIBLE Institutions and Art Histories in Yemen Anahi Alviso-Marino 107 ON THE GROUND Cultural Institutions in Iraq Today Adalet R. Garmiany 119 ON THE CLOSING OF SADA FOR IRAQI ART Rijin Sahakian 125 DESIGNING THE FUTURE What Does It Mean to Be Building a Library in Iraq? AMBS Architects 137 COLLECTIVE INSTITUTIONS The Case of Palestine Jack Persekian in Conversation with Anthony Downey Table of Contents 5 149 PLAYING AGAINST INVISIBILITY PART III CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS AND THE POLITICAL Negotiating the Institutional Politics of Cultural Production ECONOMY OF GLOBAL -

Investigation Future Planning of Railway Networks in the Arabs Gulf Countries

M. E. M. Najar & A. Khalfan Al Rahbi, Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr., Vol. 1, No. 4 (2017) 654–665 INVESTIGATION FUTURE PLANNING OF RAILWAY NETWORKS IN THE ARABS GULF COUNTRIES MOHAMMAD EMAD MOTIEYAN NAJAR & ALIA KHALFAN AL RAHBI Department of Civil Engineering, Middle East College, Muscat, Oman ABSTRACT Trans-border railroad in the Arabian Peninsula dates back to the early 20th century in Saudi Arabia. Over the recent decades due to increasing population and developing industrial zones, the demands are growing up over time. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is now embarking on one of the largest modern cross-border rail networks in the world. This is an ambitious step regarding the planning and establishment of the rail network connecting all the six GCC countries. This railway network will go through at least one city in each country to link the cities of Kuwait in Kuwait, Dammam in Saudi Arabia, Manama in Bahrain, Doha in Qatar, the cities of Abu Dhabi and Al Ain in the United Arab Emirates and Sohar and then Muscat in Oman in terms of cargo and passengers. The area of investigation covers different aspects of the shared Arabian countries rail routes called ‘GCC line’ and their national rail network. The aim of this article is to study the existing future plans and policies of the GCC countries shared line and domestic railway network. This article studies the national urban (light rail transportation (LRT), metro (subways) and intercity rail transportation to appraise the potential of passenger movement and commodity transportation at present and in the future. -

South East Maidstone Urban Extension Review of Cashflow Model and Viability

South East Maidstone Urban Extension Review of cashflow model and viability Prepared on behalf of Golding Homes 20 April 2012 Final DTZ 125 Old Broad Street London EC2N 2BQ PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL www.dtz.com Review of cashflow model and viability | Golding Homes Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Basis of Instruction 4 2 Golding Homes Financial Model Structure 5 2.1 Key Scheme Details 5 2.2 The Financial Model 6 3 Review of Revenue Assumptions 8 3.1 Revenue 8 3.1.1 Market Sale Housing 8 3.1.2 Affordable Housing 9 3.2 Future House Prices, Absorption and Sales Rates 10 3.2.1 Assumptions about Sales/ Build Out Rates 11 3.3 New Homes Bonus 12 3.4 Current Housing Land Supply 12 4 Review of Cost Assumptions 14 4.1 Cost 14 4.1.1 Unit Sizes 14 4.1.2 Build Costs 14 4.1.3 Code for Sustainable Homes 15 4.1.4 Cost Inflation 15 4.2 On Costs 16 4.3 Planning Contributions (CIL & s106) 17 4.4 Finance Rate 18 4.5 Infrastructure Costs 19 4.6 Land Value 20 4.7 Profit 20 5 Scenario Analysis 22 6 Summary 24 6.1 Delivery Structure 24 6.2 Financial Returns 24 Final 2 Review of cashflow model and viability | Golding Homes Status of Report and Limitations This report contains information which may be commercially sensitive if released. Circulation should be limited to appropriate individuals within Golding Homes. The contents of this report are confidential to Golding Homes in the context in which the report is supplied and DTZ expressly disclaims any responsibility towards third parties in respect of the whole or any part of its contents. -

Urban Development in the Arabian Peninsula

6 The Journal of the International Institute Fall 2008 United Kingdom, Belgium, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Aus- Urban Development tralia, France, and the Indian Subcontinent. One of these is Michigan State University, which recently established a branch campus in DIAC and enrolled its inaugural class in the Arabian Peninsula this fall. The UAE is not alone in its international education pursuits. Neighboring Qatar is also taking strides to improve the quality of life for its citizens, including the expansion of opportunities for women and a significant investment in education and research. In Doha, Qatar’s capital, a 2,500-acre campus houses the largest number of American university branch campuses in the Middle East, or perhaps anywhere outside the United States. Known as Education City, the campus was developed under the leadership of the Qatar Foundation, an orga- nization dedicated to working collaboratively with some of the world’s finest academic and research institutions in order to move the country toward a knowledge-based economy. At present, Cornell University, Carnegie Mellon University, Georgetown University, Texas A&M Universi- ty, Northwestern University, and Virginia Commonwealth University all offer specialized degree-granting programs in Education City. Qatari and other international institu- tions dedicated to training and research are located in Education City as well. By Kirstin Olmstead and Mark Tessler These innovative and ambitious developments in ur- ban life and international education are transforming the French Culture Minister Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres (L) and French architect Jean Nouvel (R) observe the model of the future Louvre Abu Dhabi museum character of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Doha, as are compa- after a signing ceremony on March 6, 2007. -

Adept Environmental Consultancy

ADEPT ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANCY COMPANY PROFILE Contact Senathipathi Kalimuthu (Former Senior Environmental Scientist – RTI International, Abu Dhabi) M-2, Plot No. C-14, Shabiya-10 (ME-10) Mohammed Bin Zayed City, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Tel.: +971 25548777 Mob.: +971 567535789 Email: [email protected] Web Site: https://adepteco.com About Us Adept is a multidisciplinary environmental consulting firm specialized in environmental, health and safety field and providing services in variety of sectors including industries, oil and gas chemical, petrochemical, industrial and infrastructure development projects. Our consultants have excellent work experience with environmental regulatory authority and various international environmental, Health and Safety projects. Our team’s clear vision and core values allow Adept to continually deliver the highest quality of service and value to our clients across all of our consulting engagements. This has been achieved through the implementation ISO 9001-2015, ISO 14001-2015 and OSHAS 18001- 2007. We work with our clients to develop sustainable, practical and ethical solutions to the environmental challenges they face and add value to our client’s businesses by delivering excellence and innovation. Our team aims to assist our clients to ensure that the environment, workplace and communities in which they operate are mutually beneficial and safe. Mission Adept Environmental Consultancy is committed to provide cost effective, innovative, and sustainable Environment, Health and Safety (EHS) consulting services that address our client’s requirements and comply with international best practices. Vision Through achieving commercial success and full satisfaction for our clients, we seek to build a quality and sustainable future for all the stakeholders in the community by applying analytical research and providing innovative solution. -

List of References by Mbm

LIST OF REFERENCES BY MBM RAISED FLOOR RAISED FLOOR- REFERENCES PROJECT NAME CLIENT CONTRACTOR MANUFACTURER YEAR ABU DHABI WATER & ELECTRICITY AL AIN GAS TURBINE HOUSE TARGET ENGG. CONST. CO. UNIFLAIR 1993 DEPT ABU DHABI WATER & ELECTRICITY ABU DHABI GAS TURBINE HOUSE TARGET ENGG. CONST. CO. UNIFLAIR 1993 DEPT MUSSAFAH OFFSHORE ADDCAP COSTAIN ENGG. & CONST. UNIFLAIR 1994 LNG PLANT, DAS ISLAND ADGAS C.C.I.C. UNIFLAIR 1994 RENOVATION OF VILLA IN ABU DHABI PRIVATE POLENSKY & ZOELLINER UNIFLAIR 1994 BLDG. FOR MR. HATHBOUR AL RUMAITHI D.S.S.C.B. RANYA CONTG. CO. UNIFLAIR 1994 MIRFA GAS PIPELINE ADCO DODSAL PRIVATE LTD. UNIFLAIR 1995 ABU DHABI INT'L AIRPORT ABU DHABI DUTY FREE DECO EMIRATES UNIFLAIR 1995 ABU DHABI INT'L AIRPORT, EXT. TO TRANSIT ABU DHABI DUTY FREE DECO EMIRATES UNIFLAIR 1995 HOTEL GA MUBARRAZ ISLAND ADNOC TARGET ENGG. CONST. UNIFLAIR 1995 RAS AL KHAIMAH CEMENT FACTORY RAS AL KHAIMAH CEMENT COSTAIN ENGG. & CONST. UNIFLAIR 1995 RENOVATION OF COMPLEX IN ABU DHABI MINISTRY OF INTERIOR AL MANSOURI 3 B UNIFLAIR 1995 31 December 2020 2 RAISED FLOOR- REFERENCES PROJECT NAME CLIENT CONTRACTOR MANUFACTURER YEAR W.E.D. GAS TURBINE PACKAGE AT AUH & AL AIN MARUBENI CORPORATION U.T.S. KENT UNIFLAIR 1995 ETISALAT TELECOM. BLDG. AT BARAHA, DUBAI ETISALAT UNITY CONTG. CO. UNIFLAIR 1995 ETISALAT TELECOM. BLDG.AT SHJ. IND. AREA ETISALAT UNITY CONTG. CO. UNIFLAIR 1995 NATIONAL BANK OF ABU DHABI NATIONAL BANK OF ABU DHABI A.C.C. UNIFLAIR 1995 ETISALAT TELECOM. & ADMIN. BLDG. , FUJAIRAH ETISALAT COSTAIN ABU DHABI CO. UNIFLAIR 1995 ETISALAT TELECOM. & ADMIN .BLDG., RAK ETISALAT COSTAIN ABU DHABI CO. -

ISLAND LIFE at ITS BEST SUITES & VILLAS Louvre Abu Dhabi a UNIQUE DESTINATION in the CAPITAL

ISLAND LIFE AT ITS BEST SUITES & VILLAS Louvre Abu Dhabi A UNIQUE DESTINATION IN THE CAPITAL Saadiyat Island is undergoing a remarkable transformation into a world-class leisure, culturally connected and residential destination. The Louvre Abu Dhabi, also located on the island, opened in 2017 to international acclaim and has since housed historical artifacts as well as masterpieces by the likes of Da Vinci and Picasso. Abu Dhabi attractions span an array of different interests, from the city’s most pristine beach and the eco-friendly Gary Player Golf-Course on Saadiyat Island, to the historic sights of Al Ain. Visit Abu Dhabi and immerse yourself in its mesmerising variety of sights and activities. Discover Islamic art, history and philosophy, visit the impressive Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, the largest mosque in the UAE. The souk at Central Market is an excellent place to pick up a traditional Abu Dhabi souvenir. Explore a variety of regional products ranging from jewelry, carpets, antiques to traditional tailoring, fashion and diverse dining options. A trip to the desert is second to none for a memorable evening. Away from the city, trained safari guides driving 4x4 vehicles lead the thrilling journey – over the sand dunes, deep in the heart of the desert. A feast under the stars include a Middle Eastern selection of grilled meats, Arabic mezzeh, fresh salads and aromatic shisha at a traditional Bedouin-style camp. Jumeirah at Saadiyat Island Resort - Beach JUMEIR AH AT SAADIYAT ISLAND RESORT, ABU DHABI Jumeirah at Saadiyat Island Resort, a breath of fresh air and understated luxury arrives to the Abu Dhabi shores. -

Consultees for the Implementation of the Sustainable Drainage

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs December 2011 Consultees list for the consultation on national build standards and automatic adoption arrangements for gravity foul sewers and lateral drains Contents About this document ................................................................................................................. 1 Our consultees ......................................................................................................................... 1 About this document The consultation describes how Government proposes to implement the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 (the Act) for the construction standards and automatic adoption of new- build sewers England. It should be noted that this list of consultees is not exhaustive. We welcome views from anyone expressing an interest in the consultation. Although not specified on the list, some individuals and all the local authorities in England have been contacted. These authorities include borough, district, city and county councils. It should be noted that the Welsh Government is consulting separately on this subject. Our consultees 2B Landscape Consultancy 365 Environmental Services 3e Consulting Engineers Ltd A.L.H. Environmental Services Aberyswyth University ACO Technologies plc Alde and Ore Association Allen Pyke Association Albion Water Allianz Insurance All Internal Drainage Boards All Local Authorities All Parliamentary Group on sewers and sewerage All Parliamentary Group on Water Amey Anglian (Central) Regional Flood Defence Committee Anglian -

Balfour Beatty - VINCI Joint Venture Is Awarded the Contract for HS2’S Main Civil Engineering Works Packages Lots N1 and N2 in the United Kingdom

Rueil Malmaison, 15 April 2020 Balfour Beatty - VINCI joint venture is awarded the contract for HS2’s main civil engineering works packages lots N1 and N2 in the United Kingdom • Construction contract following the successful completion of 2.5 years of design • Two lots valued at c. £5 billion, about €5.75 billion • More than 200 engineering structures over 90km near Birmingham The 50:50 joint venture between Balfour Beatty and VINCI* has been awarded the HS2 lots N1 and N2 phase 2 contract (construction) on 1 April 2020. Lot N1 and Lot N2 are between the Long Itchington Wood Green tunnel to the Delta Junction / Birmingham Spur and from the Delta Junction to the West Coast Main Line tie-in respectively. Phase 1 for these contracts had been awarded in July 2017 for the design of the West Midlands area. More than 500 engineers and technicians, including the joint venture’s designers, worked successfully to reach this milestone today and enable the project to switch from design to construction. Spanning on approximately 90km, the delivery of Lot N1 and Lot N2 will include an impressive number of engineering structures, tunnels and earthworks: 51 viaducts and boxes totalling over 14km and 76 overbridges, 7.5km of twin tunnel, 35 cuttings reaching over 30km, 76 culverts and other underbridges, 66 embankments reaching over 33km, 4 motorway crossings requiring box structures, and 6 interfaces with existing rail requiring both dive-under and overbridge structures. Lots N1 and N2 comprise a total of 1.8 million cubic meters of concrete and 32 million cubic meters of cut and landfill.