Woolly Nightshade Bio-Control Agent Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Information

2020 Mount Maunganui Intermediate School 21 LODGE AVENUE, MOUNT MAUNGANUI 3116 Index: Adolescent Health Nurse Attendance Lunchonline Communications Eligibility and Enrolment Enrolment Scheme Enrolment Packs Information Evening Open Day Enrolments Close Accelerate Testing Accelerate & Whanau Class Notification Orientation Visits School Zone Coastal Values Donations Other Payments Health and Emergencies International Students Medical Precautions Money [Bank A/c No. for Student Payments] Mufti Days Parent Support Group Permission to Leave School Personal Belongings Road Safety School Bus Transport School Hours Stationery Packs BYOD Uniform Expectations Reporting to Parents Learning Conferences Specialist Programme Home School Partnerships Smokefree School Use of School Telephone Visiting the School Emergency Procedures Personnel [as at August 2019] GENERAL INFORMATION Adolescent Health Nurse An adolescent health nurse from BOP District Health Board (Community Child and Youth Health Services) visits the school regularly, offering free health services. The nurse accepts self- referrals from students, as well as referrals from parents, caregivers and staff. Contact with parents is valued and welcomed. Attendance It is an official requirement that we obtain an explanation every time a pupil is absent. The office can be contacted between 8.00am and 8.30am to inform us of daily absences. Phone No. 07 575 5512 [extn 1] Absentee Text Only 027 232 0446 Email [email protected] Class roll is taken every morning and afternoon. Parents are contacted by text and/or email if the school is not informed of reasons for absences. Doctor and dentist appointments should be, as far as possible, made out of school hours. However, please notify the school in advance, if your child needs to go to an appointment during school hours. -

13A Waimapu Estuary/Welcome Bay Published Date October 2018

T eiha e na R T g e e o u id a en e Wharf Street d Bethlehem Road Av R c A au ie la ce n B P a almed rr Spring Street d our Te Motuopae Island (Peach Island) m n ey ld a S e r i t kf aghs arr R S Bellevue Roado D oa d Selwyn Street o e d r a h Maheka Point Waipu Bay B Ro T T e e h ONFL 3 Grey Street ONFL 3 k s e r i D a Driv l d e R r el iv C fi d e h s t n t A a h TAURANGA l r g T i ad e o Ro e ood Second Avenue P m st H w u e W e C ings Thi g K rd n a Fourth Avenue d Av a r Millers Road en ri m d ue S e k ich oa u w t ael R a a T n d H t e e a i Sutherland Road o o Pa v d n e R a A r a Wairoa Pa o S Seventh Avenue o R r e a R o e o d Sixth AvenueFifth Avenue t ad R u s M a l o o J n a m on Stree i t K t k a a h et tre Otumoetai Road s p d C i S d ih n n a Eighth Avenue o i ho o H S l t t o a hway 2 na R t Pa State Hig o ll io ra Waihi Road i d e n u D c T J h v h a t a i D e c R r iv e riv m e e Str r oa o r R a ne u i D ai h d e e t h k B aum e P o ar C i Pembr is B a P ou Bell Street p l R a a leva A ob t a c r r in d h d ik s a Edgecumbe Road a w e i Ro Matapihi M ts n Tani h ui g D St John Street ei t Way H riv e m e e is e tr Norris Street t g leh W Re S S h Waikari Road et S o i B e k T n i t enu w e Bi h Av e e inch rc m e r m n l W e o lf Eleventh Avenue i t La n ste o r h a e g r T A k g e K v G r e n ra e a e ce n r a u r O iv e s r t Christopher Street Dr ive D e d Puwhariki Road l D a o W y w ri e v e Devonport Road tl e r s e a sm T Gra Harvey Street C o Briarley Street lder Lane w Fifteenth Avenue E n h d ea a d o C Seventeenth -

Item 8.1 Welcome Bay and Ohauiti Planning Study 2020

Welcome Bay and Ohauiti Planning Study 2020 City Planning Team Welcome Bay and Ohauiti Planning Study 2020 Welcome Bay and Ohauiti Planning Study 2020 Document control Rev. No Date Author Comment Reviewed by 1 2020-08-4 S Tuck Revision 1 for review. A Greenway, A Mead, A Talbot, B McDonald, C Abbiss, C Larking, J Speedy, K Dawkings, P Siemensma 2 2020-08-12 S Tuck Revision 2 for review. J Speedy 3 2020-08-13 S Tuck Revision 3 for review. A Mead 4 2020-08-17 S Tuck Revision 4: Version for C Jones executive briefing. 5 2020-08-25 S Tuck Revision 5: Final version C Jones. with updated recommendations. 1 Welcome Bay and Ohauiti Planning Study 2020 Contents Welcome Bay and Ohauiti Planning Study 2020 .................................................................................... 1 Executive summary ................................................................................................................................ 3 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................. 7 Purpose.................................................................................................................................................. 8 Background and Context........................................................................................................................ 9 Tauranga City ................................................................................................................................... 9 Study Area overview .........................................................................................................................12 -

Wai 215 Tauranga Moana Inquiry OFFICIAL

OFFICIAL Wai 215, S7 Wai 215 Tauranga Moana Inquiry THE TANGATA WHENUA EXPERIENCE OF ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENTS (INCLUDING TOWN AND DISTRICT PLANNING) IN THE TAURANGA MOANA INQUIRY DISTRICT SINCE 1991 A STUDY OF ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING IN TAURANGA MOANA SINCE 1991 Prepared for Corban Revell and Waitangi Tribunal by Boffa Miskell Limited September 2006 A STUDY OF ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING IN TAURANGA MOANA SINCE 1991 Prepared by: Level 2 ____________________ 116 on Cameron Antoine Coffin Cnr Cameron Road and Wharf Street Senior Cultural Advisor PO Box 13 373 Tauranga 3030, New Zealand Telephone: +64 7 571 5511 Facsimile: +64 7 571 3333 and Date: 12 September 2006 Reference: T06096_006 Peer review by: Status: Final ____________________ Craig Batchelar Senior Principal Planner This document and its content is the property of Boffa Miskell Limited. Any unauthorised employment or reproduction, in full or part is forbidden. WAITANGI TRIBUNAL A STUDY OF ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING IN TAURANGA MOANA SINCE 1991 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Brief ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Personnel.......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Methodology.................................................................................................................................. -

Targa Rotorua 2021 Leg 1 Saturday 22Nd

H O G Waihi T G N Orokawa Bay D N A O aikino O Waihi Beach T R N K RA IG F TR SEAFORTH WA IHI RDFERGUS OL BEACH D FORD Island View TA UR A A Waimata R NG E A Bay of Plenty W R Athenree S D S E K D P U E P N N A ATHENREE C L E D Bowentown O T O Katikati N I W O Entrance 2 P S WOLSELEY R E N N HIKURANGI TA O W IR O P SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN O TU A D KAIMAI L A ONGARE POINT N AMAKU W D Tahawai I INT M LL K I PO SERVATION OU AUR a GH ta Karewa BY k PARK Woodlands a Island LIN n TargaDEMANN Rotorua 2021a ai Katikati D Is R la WHA EY n RAW RA L d HA ET RD T P TIR EA RD AR OH R SH AN W 2 Leg 1 G A A IR D Tauranga A R UI K S H A RING TA Harbour WAIHIRERE U P D S R A R M T D OPUHI RD D O N M H U K Aongatete A SaturdayL C 22ndMATAKANA PTMayT A A TR E K S N G AN N O ID A haftesbury SO T T P G D RD RE S Omokoroa Wairanaki M IN R O P O K F Bay TH OC L Pahoia L A Beach ru Mt Eliza HT T IG W E D A 581 D R Apata R N Mount Maunganui R W A Motiti Island O A O H K L R Tauranga A W O P K A U A E O G I Omokoroa ARK M I M Harbour O N W O Wairere R O K U A L C D Bay I I O Motunau Island O S L N D B O 2 Taumaihi (Plate Island) S R U N 2 A Otumoetai R S TAURANGA O P T D Island D MARANUI ST A K H A S Gordon R R R P G I E O R G Te N Kaimai Railway TunnelR A D L D I W U Tauranga D O A W Puna A O Bethlehem R M N Airport N D A e Y S M S U O P G M E I A R A N O R I Te Maunga P T R M O F 2 A E O A M DVILLE A F 29A O R A GOODWIN S W A A T DR B D S M Minden TOLL Kairua EA Papamoa Beach R D CH A OR Ngapeke S K F Waitao Y A W E U R A R N D E Whakamarama H D CR G IM Greerton -

Draft Welcome Bay Community Plan

The Welcome Bay Community Plan November 2011 The Welcome Bay Project Logo Ko Mauao toku Maunga Mauao is our Mountain Ko Tauranga toku Moana Tauranga is our Harbour Ko Ngai Te Rangi, Ngati Ranginui raua ko Ngati Pukenga toku Iwi Ngai Te Rangi, Ngati Ranginui and Ngati Pukenga are our People Ko Mataatua raua ko Takitimu toku waka Mataatua and Takitimu are our canoes Ko Nga Papaka o Rangataua toku kainga The Rangataua Harbour is our home Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena ra koutou katoa Greetings The logo represents Welcome Bay as a growing, vibrant and evolving community and this is depicted by the large koru in the centre of the logo. The three notches on the left hand side of the central koru represents the 3 Iwi of Tauranga Moana and the four smaller koru to the right of the logo represents all the different sectors in our community; social, economic, environmental and the cultural components that contribute to the wellbeing and aspirations of Welcome Bay’s unique beauty. The turquoise colour represents Nga Papaka o Rangataua, the harbour that sustains us with food, recreation and a rich lifestyle. The purple represents the spirit of the People, the knowledge, passion and commitment that nourishes the lifeline of the past, present and our future as a community. The Welcome Bay Project, the Welcome Bay Community Centre and the Community Project Team acknowledge and thank Quaid Tata who as a local 18 year old woman living with her whanau in Welcome Bay designed the logo for the Welcome Bay Community Plan. -

Smartgrowth Maori and Tangata Whenua Iwi Demographics 2015

Report SmartGrowth Maori and Tangata Whenua Iwi Demographics 2015 Prepared for SmartGrowth Prepared by Beca Ltd 6 August 2015 SmartGrowth Maori and Tangata Whenua Iwi Demographics 2015 Revision History Revision Nº Prepared By Description Date 1 Genevieve Doube 1st Draft 2 Shad Rolleston 2nd Draft 5 August 2015 3 4 5 Document Acceptance Action Name Signed Date Prepared by Genevieve Doube Reviewed by Shad Rolleston Approved by Christine Ralph on behalf of Beca Ltd © Beca 2015 (unless Beca has expressly agreed otherwise with the Client in writing). This report has been prepared by Beca on the specific instructions of our Client. It is solely for our Client’s use for the purpose for which it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Any use or reliance by any person contrary to the above, to which Beca has not given its prior written consent, is at that person's own risk. i SmartGrowth Maori and Tangata Whenua Iwi Demographics 2015 Executive Summary This report has been prepared by Beca Ltd on behalf of SmartGrowth BOP to give effect to action 11C.1 Māori Demographics from the SmartGrowth Strategy 2013. Action 11C.1 states: Prepare a report from 2013 census data (and document methodology used) that relates to tangata whenua iwi and Māori in the areas of housing, employment, education and income (among others) for the purpose of developing a base platform from which to compare future demographics trends and community needs. This report provides a demographic snapshot about Māori and tangata whenua iwi1 in the SmartGrowth Sub-Region based on Census 2013 data. -

Lighting up the Bay for Over 10 Years

Whangamata Download Papamoa your digital n 104 Doncaster Drive n 606 Linton Crescent n 30 Bucklands Crescent copy from n 5 Koro Mews bayofplentytimes.co.nz / n 54b Hartford Avenue Christmas promotions n 9 Aranui Drive n 6 Enterprise Drive Katikati Light Trail 2013 n 11 Longmynd Drive n 123 Park Road Waihi n 2 Major Street Lighting up the Bay for over 10 years n 53 Papaunahi Road n 53 Papaunahi Road (Bowentown) n 14 Clarke Street n 23 Mataura Road Mount n 1 Margaret Street Bethlehem Maunganui n Bethlehem Town Centre n 47 Crane Street – 19 Bethlehem Road n 55a Maranui Street n 77 Maunganui Road Maungatapu n Apt 20 The Palms, 60 Maranui Street Tauranga n 12 Te Ngaio Road BE IN TO Omokoroa n 100 Thirteenth Avenue n 383a Maungatapu Road n Bayfair Shopping Centre Bethlehem Town Centre: n 3 Plover Place – Corner Maunganui & n n 16 Woods Avenue 84 Harbour View Road n 5 Plover Place Home to the largest Christmas n 201 Darraghs Road Girven Roads n 9 Plover Place tree in the Bay n 45 Fraser Street WIN! n 12 Plover Place n 47 Maxwells Road n 18 Plover Place n Bay of Plenty Times – 405 Cameron Road n Tauranga Waterfront – Downtown Tauranga Gate Pa Te Puke Greerton / n 4 Neil Place n 1 Allanah Place To enter just upload a photo n Above & Beyond Education n 61 Jellicoe Street Pyes Pa & Care Centres to Facebook of yourself n n – 1 Rimu Street 7 Washer Place ‘doing the Trail’ and tag the 208 Cheyne Road Welcome Bay n 9 Danny Place n Te Puke Baptist Church Bay of Plenty Times. -

Section 18 – Rural 1

Section Contents Rural .................................................................................................... 2 18. Rural ................................................................................................................. 2 Explanatory Statement ................................................................................................... 2 18.1 Significant Issues ............................................................................................... 4 18.2 Objectives and Policies ....................................................................................... 7 18.3 Activity Lists ..................................................................................................... 10 18.4 Activity Performance Standards ......................................................................... 15 18.5 Matters of Discretion ........................................................................................ 44 Section 18 – Rural 1 Rural 18. Rural Explanatory Statement The Western Bay of Plenty District is predominantly a rural area with a number of small towns spread throughout. Rural production is the primary economic driver and the District is reliant on the efficient use of the rural land resource to sustain this production. The rural area is made up of a number of physically discrete landforms. To the north west lies the Kaimai Range which is characterised by steep elevated ridges and valleys, is mostly bush clad and is in large part a Forest Park. The foothills to these ranges are -

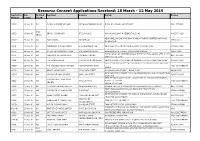

Resource Consent Applications Received: 18 March - 12 May 2019 Application Date Notified Applicant Location Details Planner Number Lodged Yes/No

Resource Consent Applications Received: 18 March - 12 May 2019 Application Date Notified Applicant Location Details Planner Number Lodged Yes/No 11369* 18-Mar-19 NO DONALD, ROBERT MICHAEL 367 MAUNGARANGI ROAD RURAL BOUNDARY ADJUSTMENT GAEL STEVENS FAST 11372* 19-Mar-19 SINGH, GURWINDER 5 FLEUR PLACE MINOR DWELLING IN RESIDENTIAL ZONE ROGER FOXLEY TRACK NEW DWELLING ENCROACHING ROAD BOUNDARY (WRITTEN APPROVAL 11368* 19-Mar-19 NO HART, MARIA 90 TIM ROAD CHRIS WATT OF ROADING) 11370* 19-Mar-19 NO WHITEMAN, RUSSELL KNIGHT 275 ATHENREE ROAD NEW SHED WITH FRONT YARD SETBACK IN RURAL ZONE ROGER FOXLEY 11373* 20-Mar-19 NO MCALISTER, LORRIMER CARLIE 614 KAITEMAKO ROAD DWELLING WITH A FRONT YARD ENCROACHMENT ANNA PRICE INSTALLATION OF SWIMMING POOL WITHIN AN ECOLOGICAL AREA (V14/2) 11376* 20-Mar-19 NO JAMIESON, CATHERINE ANN 733 MAKETU ROAD GAEL STEVENS AND A FLOOD ZONE 11380* 20-Mar-19 NO THE LODGE LIMITED 714 PYES PA ROAD (SH 36) NEW BUILDING TO PROVIDE FOR 104 BEDS FOR THE LODGE CARE HOME ROGER FOXLEY TO SELL LIQUOR ON SITE FOR THE ADDRESS INDIAN KITCHEN., HOURS OF 11389* 20-Mar-19 NO THE ADDRESS INDIAN KITCHEN 168 OMOKOROA ROAD OPERATION MONDAY TO SUNDAY 10AM TO 11PM JODY SCHUURMAN SHOP 3 11375* 21-Mar-19 NO BRAGG, HENRY EARLE 52 TAUPATA STREET BOUNDARY ADJUSTMENT - RURAL ZONE ANNA PRICE RETROSPECTIVE CONSENT FOR A 78.19M2 DWELLING AND AN ADDITIONAL 11374* 21-Mar-19 NO HEATON, SELWYN GEORGE 50 DILLON STREET ROGER FOXLEY DWELLING. CERT OF COMPLIANCE TO SELL LIQUOR ONSITE - HOURS OF OPERATION JP HOSPITALITY SOLUTIONS 11404* 25-Mar-19 NO MINDEN ROAD 9:30AM TO 10:30PM JODY SCHUURMAN LIMITED LINKED TO RC11203 11384* 25-Mar-19 NO OLD NEW ZEALAND LIMITED 665A MINDEN ROAD MINDEN 1A LIFESTYLE SUBDIVISION & MINDEN STABILITY AREA U. -

No 58, 14 September 1950, 1703

jilumll. 58 1703 NEW ZEALAND THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1950 Declaring Land Acquired for a Government Work, and Not Required SOHEDULE for that Purpose, to be Crown Land ApPROXIMATE areas of the pieces of land declared to be Orown land:- A. R. P. Being [L.S.] B. C. FREYBERG, Governor-General o 0 29· 7 "\.Parts Lot 2, D_P. 34065, being parts Allotment 10, o 0 30'3} District of Tamaki. A PROOLAMATION o 0 31·8 . URSUANT to section 35, of the Public Works Act, 1928, I, o 0 28.4 Parts Lot 4, D.P. 8264, bemg parts Allotment 10, P Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Oyril Freyberg, the Governor o 0 29.4 District of Tamaki. General of the Dominion of New Zealand, do hereby declare the land Situated in Block IX, Rangitoto Survey District (Oity of described in the Schedule hereto to be Orown land subject to the Auckland) (Auokland R.D.). (S.O. 36075.) Land Act, 1948. In the North Auckland Land District; as the same are more particularly delineated on the plan marked P.W.D. 132248, SOHEDULE deposited in the office of the Minister of Works at Wellington, and thereon coloured yellow. ApPROXIMATE areas of the pieces of land declared to be Orown land:- Given under the hand of His Excellency the Governor-General A. R. P. Being of the Dominion of New Zealand, and issued under the o 2 3·7 Lots 31 and 32, D.P. 13191, being part Section 81, Seal of that Dominion, this 7th day of September, 1950. -

Tauranga City Statistical Information Report May 2021

TAURANGA CITY STATISTICAL INFORMATION REPORT MAY 2021 Tauranga City Council Private Bag 12022, Tauranga 3143, New Zealand +64 7 577 7000 [email protected] www.tauranga.govt.nz Contents 1. Tauranga City overview ........................................................................................................... 3 2. Total population ....................................................................................................................... 5 3. Tauranga’s standing nationally ............................................................................................... 7 4. Population projections ............................................................................................................ 9 5. Population migration ............................................................................................................. 11 6. New dwellings (houses) created ........................................................................................... 15 7. New dwelling projections ...................................................................................................... 22 8. Subdivision and new sections created................................................................................. 23 9. Community age structure ...................................................................................................... 24 10. Travel to work ........................................................................................................................ 27 11. Household motor vehicle