Speak Truth to Power-A Guide for Congregations Taking Public Policy Positions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolution to Form UNITY (Unaffiliated

Resolution to Form UNITY (Unaffiliated Independent Temple Youth) In NFTY Chicago Area Region Submitted to the NFTY CAR Regional Board Winter Kallah 5777 December 17th, 2016 Background: The North American Federation of Temple Youth, or NFTY, founded in 1939, currently has nineteen regions formed by over 800 TYGs, or Temple Youth Groups. ● In 1939 NFTY was founded as part of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC), now the Union for Reform Judaism (URJ). ● In the past, TYG’s have been groups of teens from a synagogue and NFTY has served as the regional conglomerate of these entities. ● During an asefah, or plenary meeting, or during regional events, members of TYG’s vote on legislation and elect regional board members as a voting block allocated a certain number of votes based on representation. ● In recent years, as NFTY has expanded to include all Jewish youth who want a Reform Jewish experience, there has been an increase in the number of unaffiliated youth who do not receives these voting options and all privileges that may result from representation, because their families do not formally affiliate with a youth group or reform synagogue for a multitude of rationales. WHEREAS, The Preamble of the NFTY-CAR Constitution outlines the principles of the North American Federation of Temple Youth; and WHEREAS, The Preamble of the NFTY-CAR Constitution states that one of these purposes is “the need for k’hilah as a binding force for all Jews”; and WHEREAS, Article 2 of the NFTY-CAR Constitution outlines the purposes of this -

Goodnight, Sleep Tight

artist: essie jain / image: whitelilygreen.blogspot.com Goodnight sleep tight sleep No two families need do things the same way. There are no absolutes goodnight tight here with “shoulds” and “shouldn’ts.” Create a bedtime ritual that suits you and your child. Bring the memories of your own childhood bedtime ritual into the present to flavor your choices. The Shema can be the first prayer said by a child. And by teaching it to your child, you will be linking your family into a chain of tradition that stretches back two thousand years to Talmudic times. If you see yourself in a relationship with God who is in heaven and directs the world, the Shema affirms that there is only one God that we all worship. If you prefer a more mystical understanding and imagine God as not only present in the universe but that the universe is a manifestation of God, then the Shema affirms God’s unity with all creation. Some people tend to think that Jews in the past thought and did Rituals give a comforting shape to a child’s day. They offer a child a sense everything the same “orthodox” way, but Judaism has always been a of stability and security that provide a gentle transition to sleep. The pluralistic tradition that evolved and responded to the cultural milieu regularity of brushing teeth, reading a story or singing a song before being surrounding it. While the mystical approach to Judaism is less well kissed goodnight suggests to children that what they know and love is a constant and will be there again in the morning. -

Data Maturity for Synagogues: Incorporating Data Into the Decision-Making Culture Prepared by Idealware © 2014 UJA-Federation of New York

VOLUME 9 | 2015 | 5775 UJA-Federation of New York SYNERGY Innovations and Strategies for Synagogues of Tomorrow DATA MATURITY FOR SYNAGOGUES: INCORPORATING DATA INTO THE DECISION-MAKING CULTURE Prepared by Idealware © 2014 UJA-Federation of New York 1 INTRODUCTION For years, UJA-Federation of New York has been exploring how data-informed decision making can MAKINGhelp synagogues DATA PART thrive. OFThrough THE the DECISION-MAKING Sustainable Synagogues CULTUREBusiness Models project, facilitated by Measuring Success from 2009 to 2012, UJA-Federation learned that thriving synagogues regularly assess and make decisions based on the extent to which their communal vision, mission, and values are aligned with all aspects of synagogue life. We also learned that it matters which systems synagogues SELF-ASSESSMENTuse to collect data. In order TOOL to help synagogues assess which system might meet their particular needs, UJA-Federation funded the development of “A Guide to Synagogue Management Systems: Research and Recommendations,” and more recently a 2014 update, in collaboration with the Orthodox Union (OU), THEUnion DATA for ReformMATURITY Judaism PROGRESSION (URJ), and United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ). Furthermore, we have also learned through observations in the field that synagogues are not simply “data-driven or not data-driven.” Rather, there is a broad spectrum of data maturity, beginning with simple data collection and moving along the spectrum in complexity to reflect more sophisticated SUPPORTINGuses of data. THE JEWISH IDENTITY OF INDIVIDUALS AND THE COMMUNITY This paper reflects UJA-Federation's commitment to identifying and sharing innovations and strategies METHODOLOGYthat can support synagogues on their journeys to become thriving congregations. -

American Jewish Committee, Et Al

Nos. 14-1418, 14-1453, 14-1505, 15-35, 15-105, 15-119 & 15-191 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— MOST REVEREND DAVID A. ZUBIK, ET AL., Petitioners, V. SYLVIA MATHEWS BURWELL, IN HER OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SECRETARY OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL., Respondents. ———— On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Courts of Appeals for the Third, Fifth, Tenth and District of Columbia Circuits ———— BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE, JEWISH COUNCIL FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS, UNION FOR REFORM JUDAISM, AND CENTRAL CONFERENCE OF AMERICAN RABBIS IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ———— HANNA LIEBMAN DERSHOWITZ MARC D. STERN JEWISH COUNCIL FOR PUBLIC Counsel of Record AFFAIRS AMERICAN JEWISH 1775 K St. NW COMMITTEE Washington, D.C. 20006 165 East 56th Street (202) 212-6036 New York, New York 10022 [email protected] (212) 891-1480 [email protected] February 17, 2016 WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................ ii INTEREST OF AMICI ........................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................. 3 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 8 I. A SHOWING OF “SUBSTANTIAL BURDEN” REQUIRES MORE THAN AN OBJECTOR’S BELIEF, HOWEVER SINCERE, THAT HIS OR HER RELIGIOUS EXERCISE IS BEING SUBSTANTIALLY BURDENED ............. 8 II. THE BURDEN TO BE MEASURED HERE IS THE BURDEN ASSOCIATED WITH USING THE OPT-OUT ACCOMMODATION, NOT THE MONETARY FINES IMPOSED FOR NON-COMPLIANCE ................................ 16 III. PETITIONERS’ CLAIMED BURDEN FROM THE KNOWLEDGE THAT GIV- ING NOTICE OF THEIR OBJECTION WILL RESULT IN OTHERS PROVID- ING THE COVERAGE TO WHICH THEY OBJECT IS NOT ENOUGH TO INVOKE RFRA SCRUTINY ................... -

Program Title: Falafel Stand of Judaism with Trust Walk

Program Title: Falafel Stand of Judaism with Trust Walk Category: Study Theme 5765 Author(s): Sarah Ruben, NFTY PVP; Melissa Goldman, Assistant Director of NFTY Created for: URJ Kutz Camp, Kallah 2005 Touchstone Text “Throughout our history, we Jews have remained firmly rooted in Jewish tradition, even as we have learned much from our encounters with other cultures. The great contribution of Reform Judaism is that it has enabled the Jewish people to introduce innovation while preserving tradition, to embrace diversity while asserting commonality, to affirm beliefs without rejecting those who doubt, and to bring faith to sacred texts without sacrificing critical scholarship.” -from the Preamble to “A Statement of Principles for Reform Judaism” Adopted at the 1999 Pittsburgh Convention of the Central Conference of American Rabbis Goals 1. PPs will gain an understanding of the basis of Reform Judaism as a movement based on choice through knowledge and comprised of autonomous individuals 2. PPs will gain knowledge of some aspects of the evolution of the North American Reform Movement 3. PP’s will further their understanding of how they personally relate to Judaism in its many aspects. 4. PP’s will recognize how each individual connects differently to Judaism and how the Reform Movement encourages this. Objectives 1. PPs will participate in a “Walk through Jewish History,” hearing facts related to the evolution of Reform Judaism in North America and participating in some short discussions/activities on particular issues 2. PP’s will create “recipes” for their Judaism using different ingredients in falafel as different aspects of Judaism and determining how integral different elements of Judaism are to their personal connection to Judaism. -

Works Cited Primary Sources

Works Cited Primary Sources: “Alexander Schindler Collage.” Schindler Family Archives. This is a photo collage of Rabbi Schindler, his family and highlights of his career. I used this photo on my website to show how family influenced his work. Briggs, Kenneth A. “Reform Leader Urges A Program to Convert ‘Seekers’ to Judaism.” The New York Times, 3 Dec. 1978, pp. 1, 37, www.nytimes.com/1978/12/03/archives/reform-leader-urges-a-program-to-convert-seeke rs-to-judaism.html. Accessed 2 Feb. 2020. This article discusses Rabbi Alexander Schindler’s Outreach speech. I used this article for images on my website and for research on Rabbi Schindler’s outreach and inclusion proposals. Bush, Lawrence. “Working With Rabbi Alexander Schindler Toward His Acceptance of the Gay Community.” YouTube, 7 Feb. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nx2rAblpbjA&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 5 Jan. 2020. In this interview Lawrence Bush talks about his time working with Rabbi Alexander Schindler and shares how he advocated to Rabbi Schindler on the best way to offer support to the gay community. This interview was helpful because it showed how Rabbi Schindler consulted with others to elevate his understanding of how best to approach and ultimately integrate the gay community into the Reform Jewish community. Canadian Jewish News. “Image of Rabbi Denise Eger,” Canadian Jewish News, 17 Mar. 2015. This is a picture of Rabbi Denise Eger, the first openly gay president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. I used her image in my timeline. Central Conference of American Rabbis. (On) Gay And Lesbian Marriage. -

The Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism: Celebrating 50 Years in Pursuit of Social Justice!

The Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism: Celebrating 50 Years in Pursuit of Social Justice! Religious Action Center History & Influence Program Guide 60 minutes (or longer!) Audience: Adaptable for all ages Goals: • Communicate the following messages about the purpose and function of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism: o The Reform Movement has been involved in the pursuit of social justice and engaged in public policy work for many decades o The Religious Action Center, on behalf of the Reform Movement, uses many different approaches to achieve its goal of tikkun olam o The Reform Movement works on a broad range of issues that affect us as Jews, as North Americans, and as global citizens o The Religious Action Center provides a Jewish voice on important public policy issues o The Religious Action Center can support and enhance an individual’s personal social action work • Inspire program participants to become involved in the work of the Religious Action Center Timeline: 0:00-0:05 Set Induction- What is Social Justice? 0:05-0:10 Video Viewing 0:10-0:20 Conversation about what was seen on the PowerPoint 0:20-0:50 Digging Deeper: Going Through the PowerPoint (if you want the program to be longer, you can expand this section of the program) 0:50-0:60 Concluding Activity Materials: • Computer and projector (for displaying PowerPoint presentation) • RAC History Video (available for download here, or to stream on Youtube here) • RAC History PowerPoint Presentation (available for download here) • White board or butcher paper • 4 posters, which read “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,” “Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree” Program Details: 0:00-0:05 Set Induction: Advocacy, Education, & Direct Service 1) Place four posters in different corners of the room that say, “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,” “Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree.” As you read the following statements, ask participants to move to the corner of the room that best reflects their relationship to the statement. -

Jerusalem Takes Center Stage As Movement Opposes US Policy Shift

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A JTA News Briefs ........................ 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 42, NO. 16 DECEMBER 22, 2017 4 TEVET, 5778 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ A light in the face of darkness It’s a world record for largest human menorah! (JTA)—Students at a Jewish school in New Jersey broke the world record for the world’s largest human menorah. Over 500 students from Ben Porat Yosef, a private school in Paramus, stood in the shape of a Chanukah cande- labra on Wednesday morning, the first day of the Jewish holiday, Paramus Patch reported. A representative from Guinness World Records certified that the formation was indeed the largest one in the world. Sami Kuperberg and Rayna Exelbierd. Students dressed in colors to make the menorah come to life, with the younger pupils wearing red or orange to sym- bolize the flame and the older ones in white to represent the candles and dark colors to represent the menorah itself. By Christine DeSouza JSU is an after-school club that provides any high It only takes one person to school student a Jewish ex- strive to make a difference. perience through programs Sami Kuperberg is such a that strengthen their Jewish Jerusalem takes center stage as person. She had endured anti- identity. Semitism since her freshman Kuperberg planned a pro- year at Oviedo High School. gram titled “One Day Starts Students would tease her Today” with the support of movement opposes US policy shift because she is Jewish. One JOIN Orlando and StandWi- student wouldn’t let her raise thUs, a non-profit pro-Israel By Deborah Fineblum speeches and workshops, in her hand in class to answer education and advocacy or- JNS the hallways between ses- questions and grabbed her ganization that believes that sions, and over sandwiches arm and drew a swastika on education is the road to peace. -

Report of Grants Awarded: 2014 – 2015

UJA-FEDERATION OF NEW YORK REPORT OF GRANTS AWARDED: 2014 – 2015 AWARDED: REPORT OF GRANTS YORK OF NEW UJA-FEDERATION The world’s largest local philanthropy, UJA-Federation of New York cares for Jews everywhere and New Yorkers of all backgrounds, connects people to their Jewish communities, and responds to crises — in New York, in Israel, and around the world. Main Office Regional Offices New York Long Island 130 East 59th Street 6900 Jericho Turnpike New York, NY 10022 Suite 302 212.980.1000 Syosset, NY 11791 516.762.5800 Overseas Office Israel Westchester 48 King George Street 701 Westchester Avenue Jerusalem, Israel 91071 Suite 203E 011.972.2.620.2053 White Plains, NY 10604 914.761.5100 Northern Westchester 27 Radio Circle Drive Mt. Kisco, NY 10549 914.666.9650 www.ujafedny.org COMBAT POVERTY, PROMOTE DIGNITY FOSTER HEALTH AND WELL-BEING CARE FOR THE ELDERLY SUPPORT FAMILIES WITH SPECIAL NEEDS REPORT OF GRANTS AWARDED: STRENGTHEN ISRAELI SOCIETY 2014 - 2015 CONNECT JEWS WORLDWIDE DEEPEN JEWISH IDENTITY SEED INNOVATION CREATE AN INCLUSIVE COMMUNITY RESPOND TO EMERGENCIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .........................................................................................................................2 Jewish Communal Network Commission (JCNC) Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 3 Commission Membership List.................................................................................. 4 Fiscal 2015 Grants ................................................................................................... -

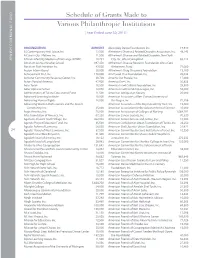

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

HM 427:8.2021A Rabbi Micah Peltz Vaccination and Ethical Questions

HM 427:8.2021a Rabbi Micah Peltz Vaccination and Ethical Questions Posed by COVID-19 Vaccines1 Approved on January 1, 2021, by a vote of 18-0-0. Voting in favor: Rabbis Jaymee Alpert, Pamela Barmash, Suzanne Brody, Nate Crane, Elliot Dorff, David Fine, Susan Grossman, Judith Hauptman, Steven Kane, Jan Kaufman, Daniel Nevins, Micah Peltz, Avram Reisner, Robert Scheinberg, David Schuck, Deborah Silver, Ariel Stofenmacher, and Iscah Waldman. Voting Against: none. Abstaining: none. Question: Now that vaccines for COVID-19 are available, is there an obligation to be vaccinated? Can Jewish institutions require vaccination for employees, students, and congregants? What should be the guidelines for their distribution? Response: The Torah commands us to “Be careful and watch yourselves,”2 which is understood by the Talmud to mean that we should avoid danger whenever possible.3 Elsewhere in Deuteronomy, we find the mitzvah of placing a parapet, or guardrail, around one’s roof.4 This is understood to mean that we should actively take steps to protect ourselves and others.5 As Rabbi Moses Isserles clearly articulates in the Shulhan Arukh, “one should avoid all things that endanger oneself, as we treat physical dangers more stringently than ritual prohibitions.”6 The Torah emphasizes that we need to take responsibility for the well-being of those around us when it says, “Do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor.”7 This is understood to mean that we do everything we can to safeguard the health of others. This is a short summary of the many sources that make it clear that taking preventative measures during this time of pandemic, like wearing masks, washing hands, and maintaining The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. -

NFTY Lingo: NFTY-CAR Has a Lot of Lingo That Is Frequently Used

NFTY Lingo: NFTY-CAR has a lot of lingo that is frequently used throughout the year at events. If you’re new to NFTY or have been just been wondering what a term a means that a NFTYite has been saying, here is your place to find it! NFTY: North American Federation of Temple Youth, we are part of one of the 19 NFTY regions. NFTY is a youth organization and a program of the Union for Reform Judaism NFTYite: One who participates in NFTY URJ: Union for Reform Judaism CAR: Chicago Area Region TYG: Temple Youth Group PVP: Programming Vice President SAVP: Social Action Vice President RCVP: Religious and Cultural Vice President CVP: Communications Vice President MVP: Membership Vice President Asefah: A board meeting with the Regional and General Board, reports are given from Regional Board members and TYGs and legislation is discussed Veida: A North American meeting that includes Asefah and a chance to propose resolutions, hear reports, and elect the NFTY North American Board Kutz: the leadership camp for the URJ Legislation: there are three forms of legislation and they are ways that anyone in NFTY-CAR can help influence our region Resolutions: State NFTY-CAR’s opinion on a certain topic, require 50% +1 simple majority By-laws: Add a new rule to NFTY-CAR’s official Constitution, requires a simple majority Amendments: Replace something that already exists in the Constitution, requires a 2⁄3 majority to pass and must be ratified at the next Asefah session PL’s: Program Leaders GL’s: Group Leaders PP’s: Participants .