Essential Understandings of Oregon Native Americans 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume I: Trail Maps, Research Methods & Historical Accounts

Coquille Indian Tribe Cultural Geography Project Coquelle Trails: Early Historical Roads and Trails of Ancestral Coquille Indian Lands, 1826 - 1875 Volume I: Trail Maps, Research Methods & Historical Accounts Report Prepared by: Bob Zybach, Program Manager Oregon Websites and Watersheds Project, Inc. & Don Ivy, Manager Coquille Indian Tribe Historic Preservation Office – Cultural Resources Program North Bend, Oregon January 4, 2013 Preface Coquelle Trails: Early Historical Roads and Trails of Ancestral Coquille Indian Lands, 1826 - 1875 renews a project originally started in 2006 to investigate and publish a “cultural geography” of the modern Coquille Indian Tribe: a description of the physical landscape and geographic area occupied or utilized by the Ancestors of the modern Coquille Tribe prior to -- and at the time of -- the earliest reported contacts with Europeans and Euro- Americans. Coquelle Trails is the first of what is expected to be several installments that will complete this renewed Cultural Geography Project. Although ships and sailors made contact with Indians in earlier years, the focus of this report begins with the first historical land-based contacts between Indians and foreigners along the rivers and beaches of Oregon’s south coast. Those few and brief encounters are documented in poorly written and often incomplete journals of men who, without maps or a true fix on their locations, wandered into and across the lands of Hanis, Miluk, and Athapaskan speaking Indians in what is today Coos and Curry Counties. Those wanderings were the first surges of the tidal wave of America’s Manifest Destiny that would soon wash over the Indians and their country. -

History of the Siletz This Page Intentionally Left Blank for Printing Purposes

History of the Siletz This page intentionally left blank for printing purposes. History of the Siletz Historical Perspective The purpose of this section is to discuss the historic difficulties suffered by ancestors of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians (hereinafter Siletz Indians or Indians). It is also to promote understanding of the ongoing effects and circumstances under which the Siletz people struggle today. Since time immemorial, a diverse number of Indian tribes and bands peacefully inhabited what is now the western part of the State of Oregon. The Siletz Tribe includes approximately 30 of these tribes and bands.1 Our aboriginal land base consisted of 20 million acres located from the Columbia to the Klamath River and from the Cascade Range to the Pacific Ocean. The arrival of white settlers in the Oregon Government Hill – Siletz Indian Fair ca. 1917 Territory resulted in violations of the basic principles of constitutional law and federal policy. The 1787 Northwest Ordinance set the policy for treatment of Indian tribes on the frontier. It provided as follows: The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and in the property, rights, and liberty, they never shall be invaded, or disturbed, unless in just, and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity shall from time to time be made for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace, and friendship with them. 5 Data was collected from the Oregon 012.5 255075100 Geospatial Data Clearinghouse. -

Indian Country Welcome To

Travel Guide To OREGON Indian Country Welcome to OREGON Indian Country he members of Oregon’s nine federally recognized Ttribes and Travel Oregon invite you to explore our diverse cultures in what is today the state of Oregon. Hundreds of centuries before Lewis & Clark laid eyes on the Pacific Ocean, native peoples lived here – they explored; hunted, gathered and fished; passed along the ancestral ways and observed the ancient rites. The many tribes that once called this land home developed distinct lifestyles and traditions that were passed down generation to generation. Today these traditions are still practiced by our people, and visitors have a special opportunity to experience our unique cultures and distinct histories – a rare glimpse of ancient civilizations that have survived since the beginning of time. You’ll also discover that our rich heritage is being honored alongside new enterprises and technologies that will carry our people forward for centuries to come. The following pages highlight a few of the many attractions available on and around our tribal centers. We encourage you to visit our award-winning native museums and heritage centers and to experience our powwows and cultural events. (You can learn more about scheduled powwows at www.traveloregon.com/powwow.) We hope you’ll also take time to appreciate the natural wonders that make Oregon such an enchanting place to visit – the same mountains, coastline, rivers and valleys that have always provided for our people. Few places in the world offer such a diversity of landscapes, wildlife and culture within such a short drive. Many visitors may choose to visit all nine of Oregon’s federally recognized tribes. -

EMPIRE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Coquille Indian Tribe

EMPIRE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Coquille Indian Tribe FINAL JULY 2018 This project is partially funded by a grant from the Transportation and Growth Management (TGM) Program, a joint program of the Oregon Department of Transportation and the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development (DLCD). This TGM grant is financed, in part, by deferral Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act), local government and the State of Oregon Funds. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect views or policies of the State of Oregon. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TRIBAL COUNCIL Brenda Meade, Chairperson Kippy Robbins, Vice Chair Donald Ivy, Chief Linda Mecum, Secretary-Treasurer Toni Ann Brend – Representative No. 1 Don Garrett – Representative No. 2 Eric Metcalf, Representative No. 3 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN WORK TEAM Loretta Kuehn, CEDCO Kassie Rippee, CIT Robin Harkins, CIT Lyman Meade, CIHA Anne Cook, CIHA Mark Healey, CIT Darin Jarnaghan, CIT Scott Perkins, Charleston Sanitary District Jill Rolfe, Coos County Planning Tom Dixon, City of Coos Bay Virginia Elandt, ODOT Rebecca Jennings, CCAT Sergio Gamino, CCAT Chelsea Schnabel, City of North Bend Mick Snedden, Charleston Fire District Matt Whitty, Coos Bay North Bend Water Board STAFF Mark Johnston, Executive Director Todd Tripp, Property and Project Manager Matt Jensen, Land Use Planner CONSULTANTS 3J Consulting Kittelson and Associates Parametrix Leland Consulting TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................1 Process Vision and Mission EXISTING -

Growing up Indian: an Emic Perspective

GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTIVE By GEORGE BUNDY WASSON, JR. A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy june 2001 ii "Growing Up Indian: An Ernie Perspective," a dissertation prepared by George B. Wasson, Jr. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. This dissertation is approved and accepted by: Committee in charge: Dr. jon M. Erlandson, Chair Dr. C. Melvin Aikens Dr. Madonna L. Moss Dr. Rennard Strickland (outside member) Dr. Barre Toelken Accepted by: ------------------------------�------------------ Dean of the Graduate School iii Copyright 2001 George B. Wasson, Jr. iv An Abstract of the Dissertation of George Bundy Wasson, Jr. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology to be taken June 2001 Title: GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E Approved: My dissertation, GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E describes the historical and contemporary experiences of the Coquille Indian Tribe and their close neighbors (as manifested in my own family), in relation to their shared cultures, languages, and spiritual practices. I relate various tribal reactions to the tragedy of cultural genocide as experienced by those indigenous groups within the "Black Hole" of Southwest Oregon. My desire is to provide an "inside" (ernie) perspective on the history and cultural changes of Southwest Oregon. I explain Native responses to living primarily in a non-Indian world, after the nearly total loss of aboriginal Coquelle culture and tribal identity through v decimation by disease, warfare, extermination, and cultural genocide through the educational policies of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. -

Overview of the Environment of Native Inhabitants of Southwestern Oregon, Late Prehistoric Era

Overview of the Environment of Native Inhabitants of Southwestern Oregon, Late Prehistoric Era Research and Writing by Reg Pullen Pullen Consulting RR 2 Box 220 Bandon,OR 97411 TELEPHONE: (503) 347-9542 Report Prepared for USDA Forest Service Rogue River National Forest, Medford, Oregon Siskiyou National Forest, Grants Pass, Oregon DOI Bureau of Land Management Medford District Office, Medford, Oregon 1996 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was directed by Janet Joyer of the United States Forest Service (Grants Pass), and Kate Winthrop of the Bureau of Land Management (Medford). Both provided great assistance in reviewing drafts of the manuscript, as did Jeff LeLande of the United States Forest Service (Medford). Individuals from three southwest Oregon Native American tribes participated in the collection of ethnographic and historic data contained in the report and appendix. Robert Kentta of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians reviewed ethnographic material from the John Harrington collection. Don Whereat of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians provided extensive help with records from the National Archives, Bancroft Library, and the Melville Jacobs collection. Troy Anderson of the Coquille Tribe helped to review materials relating to his tribe found in the Melville Jacobs collection. The staff of the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley helped to track down several early journals and diaries relating to the historic exploration of southwest Oregon. Gary Lundell of the University of Washington helped to locate pertinent materials in the Melville Jacobs collection. The staff at the Coos Bay Public Library assisted in accessing sources in their Oregon collection and through interlibrary loan. -

Pre-Visit Lesson Three

I was raised in the traditional manner of my people, meaning that I learned early Cathlamet Clatsop in my life how to survive. Skilloot Clatskanie Nehalem Wh So I grew up speaking my language, at natur ltnom al res Mu ah ources did Tillamook Tribes tr ade with each other? learned how to forage for wild foods, T u a la tin tuc Nes ca Walla Walla Chafan (Dog River) Cascades (Dalles) digging for roots and bulbs with my mother Salmon River Yamhill Clackamas Wasco Ahantchuyuk Siletz and her aunties, trapping small game Luckiamute Tenino Yaquina Santiam Wyam with my grandfather and learning Chepenefa Tygh Alsea Chemapho Northern John Day food preparations early in my life. Tsankupi Molalla Nez Perce Siuslaw enino — Minerva Teeman Soucie Long Tom Mohawk T Wayampam Burns Paiute Tribe Elder Chafan ( ) Umatilla Cayuse The Grande Ronde Valley Kalawatset Winefelly was our Eden. Everything was there Hanis Yoncalla Miluk Southern Wa-dihtchi-tika for the people . The camas root was in Molalla Upper ppe Coquille U r Umpqua Kwatami Hu-nipwi-tika (Walpapi) abundance. When the seasons came there, Yukichetunne Tutuni Cow Creek onotun sta Mik ne Co sta the people from here went over to Chemetunne ha S Taltushtuntede Chetleshin (Galice) Pa-tihichi-tika ishtunnetu Kwa nne Takelma Wada-tika the Grande Ronde Valley and dug the camas. Chetco Upland Takelma D Klamath Tolowa aku Yapa-tika — Atway Tekips (Dan Motanic) be te de Agai-tika Shasta Modo c Gidi-tika MAJOR NATIVE AMERICAN LANGUAGES OF OREGON UTO-AZTECAN Northern Paiute Gwi-nidi-ba Wa-dihtchi-tiki, Hu-nipwi-tika, -

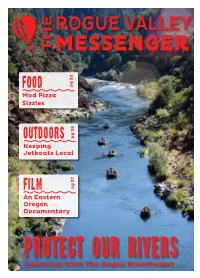

Protect Our Rivers Interview with the Rogue Riverkeeper 2

Volume 4, Issue 14 // July 6 - July 19, 2017 FOOD pg 22 Mod Pizza Sizzles OUTDOORS pg 26 Keeping Jetboats Local FILM pg 27 An Eastern Oregon Documentary Protect our rivers Interview With The Rogue Riverkeeper 2 / WWW.ROGUEVALLEYMESSENGER.COM SUMMER EXHIBITIONS Tofer Chin: 8 Amir H. Fallah: Unknown Voyage Ryan Schneider: Mojave Masks Liz Shepherd: East-West: Two Streams Merging Wednesday, June 14 through Saturday, September 9, 2017 The Summer exhibitions are funded in part by a generous donation from Judy Shih and Joel Axelrod. MUSEUM EVENTS Tuesday Tours: IMAGES (LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM, DETAILS): Tofer Chin, Overlap No. 3, 2016, Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 34” Free Docent-led Tours of the Exhibitions Amir H. Fallah, Unknown Voyage, 2015, Acrylic, colored pencil and collage on paper mounted on canvas, 48 x 36” Ryan Schneider, Many Headed Owl, 2016, Oil on canvas, 60 x 48” Liz Shepherd, Mount Shasta at Dawn, 2012, Watercolor on riches paper, 19.5 x 27.5” Tuesdays at 12:30 pm MUSEUM HOURS: MONDAY – SATURDAY, 10 AM TO 4 PM • FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC mailing: 1250 Siskiyou Boulevard • gps: 555 Indiana Street Ashland, Oregon 97520 541-552-6245 • email: [email protected] web: sma.sou.edu • social: @schneidermoa PARKING: From Indiana Street, turn left into the metered lot between Frances Lane and Indiana St. There is also limited parking behind the Museum. JULY 6 – JULY 19, 2017 / THE ROGUE VALLEY MESSENGER / 3 The Rogue Valley Messenger PO Box 8069 | Medford, OR 97501 CONTENTS 541-708-5688 page page roguevalleymessenger.com FEATURE FOOD [email protected] Rivers are the lifeblood Mod Pizza is a THE BUSINESS END OF THINGS that flows throughout Seattle-based chain. -

Four Deaths: the Near Destruction of Western

DAVID G. LEWIS Four Deaths The Near Destruction of Western Oregon Tribes and Native Lifeways, Removal to the Reservation, and Erasure from History THE NOTIONS OF DEATH and genocide within the tribes of western Oregon are convoluted. History partially records our removal and near genocide by colonists, but there is little record of the depth of these events — of the dramatic scale of near destruction of our peoples and their cultural life ways. Since contact with newcomers, death has come to the tribes of western Oregon in a variety of ways — through epidemic sicknesses, followed by attempted genocide, forced marches onto reservations, reduction of land holdings, broken treaty promises, attempts to destroy tribal culture through assimilation, and the termination of federal recognition of sovereign, tribal status. Death, then, has been experienced literally, culturally, legally, and even in scholarship; for well over a century, tribal people were not consulted and were not adequately represented in historical writing. Still, the people have survived, restoring their recognized tribal status and building structures to maintain and regain the people’s health and cultural well-being. This legacy of death and survival is shared by all the tribes of Oregon, though specific details vary, but the story is not well known or understood by the state’s general public. Such historical ignorance is another kind of death — one marked by both myth and silence. An especially persistent myth is the notion that there lived and died a “last” member of a particular tribe or people. The idea began in the late nineteenth century, when social scientists who saw population declines at the reservations feared that the tribes would die off before scholars could collect their data and complete their studies. -

Land Acknowledgement Acknowledgement Is Critical In

Land Acknowledgement Acknowledgement is critical in building the necessary trust to coexist in harmony with one another. Indigenous tribes and bands have been apparent on the lands that we inhabit today in the Willamette Valley and throughout Oregon and the Northwest for time immemorial. Here in the Willamette Valley the ancestry of the Kalapuya reaches the furthest back in time, reminding us that this bountiful and plentiful Valley has been called home by its original inhabitants long before the names of the snowy peaks in the distance were reidentified. It is important to understand the significance of this as the people of this land still exist, and inhabit this Valley not as heirs to it, or archeological artifacts, but as mutual contributors to the modern society we live in. We would like to forward our respect to the First Peoples of this land, the nine Federally Recognized Tribes of Oregon, and those whose identities have been compromised as belonging to this land and who do not fall under State or Federal jurisdiction. We reflect on the displacement, forced removal, and genocides that still took place throughout Oregon and beyond, to ensure we truly honor the gravity of our past; giving a guarantee that people may live in harmony and equity on this land for posterity. We would like this acknowledgement to carry resonance as a tool of peace and mutual respect to all that reside here, who come from afar to contribute to the energy and vibrancy of the place we call home, the Sacred lands of the Willamette Valley. -

Oregon's History

Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden ATHANASIOS MICHAELS Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden by Athanasios Michaels is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Contents Introduction 1 1. Origins: Indigenous Inhabitants and Landscapes 3 2. Curiosity, Commerce, Conquest, and Competition: 12 Fur Trade Empires and Discovery 3. Oregon Fever and Western Expansion: Manifest 36 Destiny in the Garden of Eden 4. Native Americans in the Land of Eden: An Elegy of 63 Early Statehood 5. Statehood: Constitutional Exclusions and the Civil 101 War 6. Oregon at the Turn of the Twentieth Century 137 7. The Dawn of the Civil Rights Movement and the 179 World Wars in Oregon 8. Cold War and Counterculture 231 9. End of the Twentieth Century and Beyond 265 Appendix 279 Preface Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden presents the people, places, and events of the state of Oregon from a humanist-driven perspective and recounts the struggles various peoples endured to achieve inclusion in the community. Its inspiration came from Carlos Schwantes historical survey, The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History which provides a glimpse of national events in American history through a regional approach. David Peterson Del Mar’s Oregon Promise: An Interpretive History has a similar approach as Schwantes, it is a reflective social and cultural history of the state’s diversity. The text offers a broad perspective of various ethnicities, political figures, and marginalized identities. -

Request for Proposals (Rfp) Develop Sb13 Coquille Indian Tribe Culture Curriculum Coquille Indian Tribe January 15, 2020

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFP) DEVELOP SB13 COQUILLE INDIAN TRIBE CULTURE CURRICULUM COQUILLE INDIAN TRIBE JANUARY 15, 2020 Section I: Request for Proposals Purpose The Tribe invites qualified contractors to submit proposals based on the scope of work and conditions contained in this RFP. The purpose of this request for proposals (RFP) is to obtain a contractor(s) to develop culturally relevant, place based curriculum units for 6th and 11th grade about the Coquille Indian Tribe. Curriculum units/lesson plans must follow the attached lesson plan format, and be aligned with the academic content standards adopted under ORS 329.045. The units must be unique to Coquille Tribe experiences, including tribal history, sovereignty, culture, treaty rights, government, socioeconomic experiences, and current events. About The Coquille Indian Tribe is comprised of bands that historically spoke Athabaskan, Miluk, and later, Chinuk Wawa. Since time immemorial, they flourished among the forests, rivers, meadows, and beaches of a homeland encompassing well over 750,000 acres. In the mid 1850’s the United States negotiated treaties with the Coquille people. The U. S. Senate never ratified these treaties. The Coquille tribal homeland was subsequently taken without their consent. The Coquille were included in the now repudiated Western Oregon Indian Termination Act of 1954. On June 28, 1989, they were restored and tribal sovereignty was federally recognized. The Coquille Restoration Act authorized the Secretary of the Interior to take land in to trust for the Tribe. The Tribe’s land base is now approximately 10,200 acres, of which 9,800 acres are proudly managed using sustainable forestry practices.