Copyright by Carolyn Anne Olsen 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Internet of Garbage

1 The Internet of Garbage © 2015, 2018 by Sarah Jeong Cover and Illustrations by William Joel for The Verge, © 2018 Vox Media, Inc. All rights reserved. The Verge Edition 1.5 August 2018 Published by Vox Media, Inc. www.theverge.com ISBN: 978-0-692-18121-8 2 Table of Contents Preface ............................................... 4 Chapter One: The Internet Is Garbage .................. 6 A Theory of Garbage .......................................... 8 Spam as Garbage .............................................. 9 Chapter Two: On Harassment ........................... 12 Harassment in the News ...................................... 13 About That Media Narrative . ............................ 18 Is Harassment Gendered? ..................................... 20 Intersections of Harassment ................................. 21 On Doxing ................................................... 24 SWATting .................................................... 27 Doxing Women ................................................ 28 Concluding Thoughts on Doxing ............................... 30 A Taxonomy of Harassment .................................... 32 On Modern-Day Social Media Content Moderation ............... 35 What Happens Before: Setting Norms .......................... 38 Chapter Three: Lessons from Copyright Law ............ 40 The Intersection of Copyright and Harassment ................ 41 How the DMCA Taught Us All the Wrong Lessons ................ 44 Turning Hate Crimes into Copyright Crimes ................... 47 Chapter Four: A -

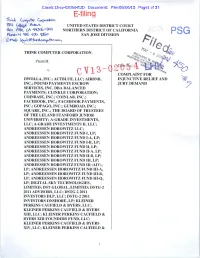

United States District Court Northern District of California San Jose Division

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN JOSE DIVISION THINK COMPUTER CORPORATION, Plaintiff, Case No.: v. COMPLAINT FOR DWOLLA, INC.; ACTBLUE, LLC; AIRBNB, INJUNCTIVE RELIEF AND INC.; POUND PAYMENTS ESCROW JURY DEMAND SERVICES, INC. DBA BALANCED PAYMENTS; CLINKLE CORPORATION; COINBASE, INC.; COINLAB, INC.; FACEBOOK, INC.; FACEBOOK PAYMENTS, INC.; GOPAGO, INC.; GUMROAD, INC.; SQUARE, INC.; THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE LELAND STANFORD JUNIOR UNIVERSITY; A-GRADE INVESTMENTS, LLC; A-GRADE INVESTMENTS II, LLC; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ LLC; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND I, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND I-A, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND I-B, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND II, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND II-A, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND II-B, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III (AIV), LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III-A, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III-B, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III-Q, LP; DIGITAL SKY TECHNOLOGIES, LIMITED; DST GLOBAL, LIMITED; DSTG-2 2011 ADVISORS, LLC; DSTG-2 2011 INVESTORS DLP, LLC; DSTG-2 2011 INVESTORS ONSHORE, LP; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS XIII, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS XIII FOUNDERS FUND, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS XIV, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & 1 BYERS XV, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL NEW PROJECTS, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL XII, LP; SC XII MANAGEMENT, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL XII PRINCIPALS FUND, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL SCOUT FUND I, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL SCOUT FUND II, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL U.S. SCOUT FUND III, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL U.S. SCOUT SEED FUND 2013, LP; SEQUOIA TECHNOLOGY PARTNERS XII, LP; Y COMBINATOR, LLC; Y COMBINATOR FUND I, LP; Y COMBINATOR FUND I GP, LLC; Y COMBINATOR FUND II, LP; Y COMBINATOR FUND II GP, LLC; Y COMBINATOR RE, LLC; Y COMBINATOR S2012, LLC; Y COMBINATOR W2013, LLC; BRIAN CHESKY; MAX LEVCHIN; YURI MILNER; YISHAN WONG, Defendants. -

Facultad De Ciencias De La Educación TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN UNIVERSIDAD DE MÁLAGA Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO GRADO EN PEDAGOGÍA La inclusión de la robótica y el pensamiento computacional en la educación obligatoria Realizado por: Javier Montero González Tutorizado por: Carmen Rodríguez Martínez Curso 2020-2021 FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN UNIVERSIDAD DE MÁLAGA TÍTULO: La inclusión de la robótica y el pensamiento computacional en la educación obligatoria. RESUMEN: Por una apuesta decidida de la Unión Europea, a nivel nacional y desde el año pasado en Andalucía, la robótica y el pensamiento computacional se han incluido oficialmente en el currículum de Educación Primaria y Educación Secundaria, al igual que en otras regiones de nuestro país. El objetivo de esta investigación es investigar dicha inclusión, comprender qué motivaciones políticas y económicas puede haber, así como los beneficios que supone trabajar esos contenidos en el aula. Para ello, se ha llevado a cabo una investigación cualitativa que ha consistido, en primer lugar, en un análisis de la literatura relacionada con la legislación de Andalucía, España y Europa, y de aquella vinculada con el estado de la cuestión. Además, se ha llevado a cabo un Grupo de Discusión en el que han participado cuatro docentes universitarios y cuyas líneas de investigación están relacionadas, de alguna forma, con la educación y la tecnología; ya sea desde la política educativa, o directamente a través del trabajo en el aula de dichos contenidos. Los resultados más importantes de esta investigación señalan que los motivos por los que se incluyen estos contenidos en la educación obligatoria no responden a un criterio neutral, sino que existen evidentes motivaciones tanto políticas como económicas para hacerlo. -

The Fintech Book Paint a Visual Picture of the Possibilities and Make It Real for Every Reader

Financial Era Advisory Group @finera “Many are familiar with early stage investing. Many are familiar with technology. Many are “FinTech is about all of us – it’s the future intersection of people, technology and money, familiar with disruption and innovation. Yet, few truly understandFinancial how different Era an animal Advisory and it’s happeningGroup now there is an explosion of possibilities on our doorstep. Susanne and is the financial services industry. Such vectors as regulation, compliance, risk, handling The FinTech Book paint a visual picture of the possibilities and make it real for every reader. other people’s money, the psychological behaviours around money and capital ensure A must-read for every disruptor, innovator, creator, banker.” that our financial services industry is full of quirks and complexities. As such The FinTech Derek White, Global Head of Customer Solutions, BBVA Book offers a refreshing take and knowledge expertise, which neophytes as well as experts will be well advised to read.” “FinTech is reshaping the financial experience of millions of people and businesses around Pascal Bouvier, Venture Partner, Santander InnoVentures the world today, and has the potential to dramatically alter our understanding of financial services tomorrow. We’re in the thick of the development of an Internet of Value that will “This first ever crowd-sourced book on the broad FinTech ecosystem is an extremely deliver sweeping, positive change around the world just as the internet itself did a few worthwhile read for anyone trying to understand why and how technology will impact short decades ago. The FinTech Book captures the unique ecosystem that has coalesced most, if not all, of the financial services industry. -

Regulation of Disintermediated Financial Ecosystems

Research Collection Doctoral Thesis Regulation of Disintermediated Financial Ecosystems Author(s): Elsner, Erasmus Publication Date: 2020 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000492901 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library DISS. ETH NO. 26989 REGULATION OF DISINTERMEDIATED FINANCIAL ECOSYSTEMS A thesis submitted to attain the degree of DOCTOR OF SCIENCES of ETH ZURICH (Dr. sc. ETH Zurich) presented by ERASMUS ELSNER M.A, University of Zurich born on 13.08.1985 citizen of Zurich accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Stefan Bechtold Prof. Ryan Bubb Prof. Christoph Stadtfeld 2020 Abstract The overarching theme of this PhD thesis is the analysis of the interplay between regulation and financial intermediation. The research focuses on the analysis of the role played by security laws and industry-specific financial regulation in shaping the allocation through either the firm or the market. Through a law and economics perspective, the thesis tries to answer two related questions in the realm of both equity and credit markets. Firstly, it tries to establish how different regulations impose (implicit or explicit) prices on transactions and thereby either promote a market-based or a firm-based allocation mechanism. Secondly, for the competing allocative regimes, the thesis questions how the presence of both positive and negative externalities of firms and markets may favor a particular allocation mechanism. The PhD project is divided into five separate chapters, with each one examining different aspects of the law and economics of financial intermediation. -

Social News Sites As Democratic Media an Evaluative Study of Reddit's Coverage of the 2012 US Presidential Election Campaign Szabo, András

Social News Sites as Democratic Media An evaluative study of Reddit's coverage of the 2012 US presidential election campaign Szabo, András Publication date: 2013 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Szabo, A. (2013). Social News Sites as Democratic Media: An evaluative study of Reddit's coverage of the 2012 US presidential election campaign . Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN PhD thesis András Szabó Social News Sites as Democratic Media An evaluative study of Reddit's coverage of the 2012 US presidential election campaign Academic advisor: Klaus Bruhn Jensen Submitted: 30/09/13 Institutnavn: Institut for Medier, Erkendelse og Formidling Name of department: Department of Media, Cognition and Communication Author: András Szabó Titel og evt. undertitel: Sociale nyhedswebsites som demokratiske medier: En empirisk og teoretisk-normativ evaluering af Reddits dækning af den amerikanske præsidentvalgkamp i 2012 Title / Subtitle: Social News Sites as Democratic Media: An evaluative study of Reddit's coverage of the 2012 US presidential election Subject description: Empirical analysis and normative theoretical evaluation of social news site Reddit's coverage of the 2012 US presidential election. Reddit, although nominally democratic, is shown in general to be failing to meet normative criteria derived from three ideal types of democracy; a way of salvaging its democratic potential is proposed. Academic advisor: Klaus Bruhn Jensen Submitted: 30. September 2012 Grade: 2 Abstract This thesis presents an empirical analysis and normative theoretical evaluation of Reddit, a social news website, focusing on its coverage of the 2012 US presidential election campaign. -

“No Place” in Cyberspace

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 “No Place” in CyberSpace Scarlett Sinay Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the American Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Sinay, Scarlett, "“No Place” in CyberSpace" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 138. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/138 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “No Place” in CyberSpace 1 Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Scarlett Sinay Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 1 Image designed by Nicolás Vargas. Originally posted to their account @blackpowerbottomtext, on Instagram. 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincerest appreciation and gratitude to my thesis advisors, Kenneth Stern and David Shein. This project was made possible by your combined and unfaltering mentorship and encouragement. A very special thanks to Anna Gjika and Ed Halter, two past professors of mine. -

Strategies for Multi-Stakeholder Ownership in the Platform Economy

GEORGETOWN LAW TECHNOLOGY REVIEW EXIT TO COMMUNITY: STRATEGIES FOR MULTI-STAKEHOLDER OWNERSHIP IN THE PLATFORM ECONOMY Morshed Mannan* & Nathan Schneider** CITE AS: 5 GEO. L. TECH. REV. 1 (2021) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 2 A. Existing Proposals for Platform Regulation & Governance ................ 5 B. Defining terms .................................................................................... 15 C. The case of CoSocial .......................................................................... 19 II. EXIT-TO-COMMUNITY STRATEGIES .......................................................... 21 A. Option 1: Stockholding trust .............................................................. 21 1. Background .................................................................................... 24 2. Implications for Governance .......................................................... 29 3. Implications for Financial Rights ................................................... 32 4. Implications for Public Policy ........................................................ 33 B. Option 2: Federation ........................................................................... 36 1. Background .................................................................................... 40 2. Implications for Governance .......................................................... 45 3. Implications for Financial Rights .................................................. -

Think Computer V. Dwolla

Case5:13-cv-02054-EJD Document1 Filed05/06/13 Page1 of 37 E-fiting n.,i"k. Ccl"lrvt<f Corpo~ W4 (Q\\et;e tw&...x- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT AI\o A\lo, c.A "'1.3Cb'I30) NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA ~:"I % {:.70 ~ SAN JOSE DIVISION G ·t1~j\ , l~ ...\ @iWM~ ""-" THINK COMPUTER CORPORATION, Plaintiff, Y. DWOLLA, INC.; ACTBLUE, LLC; AIRBNB, INC.; POUND PAYMENTS ESCROW SERVICES, INC. DBA BALANCED PAYMENTS; CLINKLE CORPORATION; COINBASE, INC.; COINLAB, INC.; FACEBOOK, INC.; FACEBOOK PAYMENTS, INC.; GOPAGO, INC.; GUMROAD, INC.; SQUARE, INC.; THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE LELAND STANFORD JUNIOR UNIVERSITY; A·GRADE INVESTMENTS, LLC; A-GRADE INVESTMENTS II, LLC; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ LLC; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND I, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND I.A, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND I.B, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND II, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND II·A, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND II-B, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III (AIV), LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III.A, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III-B, LP; ANDREESSEN HOROWITZ FUND III·Q, LP; DIGITAL SKY TECHNOLOGIES, LIMITED; DST GLOBAL, LIMITED; DSTG-2 2011 ADVISORS, LLC; DSTG-2 2011 INVESTORS DLP, LLC; DSTG-2 2011 INVESTORS ONSHORE, LP; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS XIII, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS XIII FOUNDERS FUND, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & BYERS XIV, LLC; KLEINER PERKINS CAUFIELD & Case5:13-cv-02054-EJD Document1 Filed05/06/13 Page2 of 37 BYERS XV, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL NEW PROJECTS, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL XII, LP; SC XII MANAGEMENT, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL XII PRINCIPALS FUND, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL SCOUT FUND I, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL SCOUT FUND II, LLC; SEQUOIA CAPITAL U.S. -

Moderating a Public Scholarship Site on Reddit: a Case Study of R/Askhistorians

“I run the world’s largest historical outreach project and it’s on a cesspool of a website.” Moderating a public scholarship site on Reddit: A case study of r/AskHistorians SARAH A. GILBERT, University of Maryland, United States Online communities provide important functions in their participants’ lives, from providing spaces to discuss topics of interest to supporting the development of close, personal relationships. Volunteer moderators play key roles in maintaining these spaces, such as creating and enforcing rules and modeling normative behavior. While these users play important governance roles in online spaces, less is known about how the work they do is impacted by platform design and culture. r/AskHistorians, a Reddit-based question and answer forum dedicated to providing users with academic-level answers to questions about history provides an interesting case study on the impact of design and culture because of its unique rules and their strict enforcement by moderators. In this article I use interviews with r/AskHistorians moderators and community members, observation, and the full comment log of a highly upvoted thread to describe the impact of Reddit’s design and culture on moderation work. Results show that visible moderation work that is often interpreted as censorship, and the default masculine whiteness of Reddit, create challenges for moderators who use the subreddit as a public history site. Nonetheless, r/AskHistorians moderators have carved a space on Reddit where, through their public scholarship work, the community serves as a model for combating misinformation by building trust in academic processes. CCS Concepts: • Human-centered computing → Computer supported cooperative work. -

Curating the Future : the Sustainability Practices of Online Hate Groups

CURATING THE FUTURE: THE SUSTAINABILITY PRACTICES OF ONLINE HATE GROUPS By Julia Rose DeCook A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Media and Information Studies — Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT CURATING THE FUTURE: THE SUSTAINABILITY PRACTICES OF ONLINE HATE GROUPS By Julia Rose DeCook The rise of populist fascism and hate violence across the world has raised alarm bells about the nature of the Internet in the radicalization process. Although there have been attempts in recent years to halt the spread of extremist discourse online, these groups remain and continue to grow. The purpose of this dissertation project was to examine online extremist groups’ responses to infrastructural failure, which was defined as an event such as deplatforming and other modes of censorship, to understand how these groups manage to persist over time. Examining the responses of three groups to these failures, r/TheRedPill; r/Incels and Incels.me; and r/AznIdentity; who are affiliated with the larger “Manosphere” (a loosely connected online network of men’s rights activists, Incels, Pick Up Artists, etc. connected to the alt right), what was revealed is that these groups’ practices not only build their communities and spread their discourse, but sustains them. Previous research on hate groups tends to focus on the role of Internet platforms in amplifying hate speech; the discourses the groups create; or on political strategies enacted by the groups. I argued in this dissertation project that this does not get at the heart of why these groups manage to survive despite attempts to thwart them, and that studying the material structures they are on as well as their social practices are necessary to develop better strategies to combat violent far-right extremism. -

Regulatory Entrepreneurship

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 2017 Regulatory Entrepreneurship Elizabeth Pollman University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Jordan M. Barry University of San Diego School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Technology and Innovation Commons Repository Citation Pollman, Elizabeth and Barry, Jordan M., "Regulatory Entrepreneurship" (2017). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 2556. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/2556 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGULATORY ENTREPRENEURSHIP ELIZABETH POLLMAN* & JORDAN M. BARRY† ABSTRACT This Article examines what we term “regulatory entrepreneurship”— pursuing a line of business in which changing the law is a significant part of the business plan. Regulatory entrepreneurship is not new, but it has become increasingly salient in recent years as companies from Airbnb to Tesla, and from DraftKings to Uber, have become agents of legal change. We document the tactics that companies have employed, including operating in legal gray areas, growing “too big to ban,” and mobilizing users for political support. Further, we theorize the business and law- related factors that foster regulatory entrepreneurship. Well-funded, scalable, and highly connected startup businesses with mass appeal have advantages, especially when they target state and local laws and litigate them in the political sphere instead of in court.