A Novella by Sulari Gentill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraqi Literary Response to the US Occupation

Countering the Sectarian Metanarrative: Iraqi Literary Response to the US Occupation Chad Day Truslow Waynesboro, Virginia B.A. in International Relations & History, Virginia Military Institute, 2008 M.A. in Business Administration, Liberty University, 2014 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures University of Virginia December, 2019 1 Abstract Sectarian conflict is a commonly understood concept that has largely shaped US foreign policy approach to the region throughout the modern Middle East. As a result of the conflict between Shia and Sunni militias in Iraq and the nature of Iraqi politics since 2003, many experts have accepted sectarianism as an enduring phenomenon in Iraq and use it as a foundation to understand Iraqi society. This paper problematizes the accepted narrative regarding the relevance of sectarian identity and demonstrates the fallacy of approaching Iraq through an exclusively “sectarian lens” in future foreign policy. This paper begins by exploring the role of the Iraqi intellectuals in the twentieth century and how political ideologies influenced and replaced traditional forms of identity. The paper then examines the common themes used by mid-twentieth century Iraqi literati to promote national unity and a sense of Iraqi identity that championed the nation’s heterogeneity. The paper then surveys the Iraqi literary response to the 2003 invasion in order to explain how some of the most popular Iraqi writers represent sectarianism in their works. The literary response to the US invasion and occupation provides a counter- narrative to western viewpoints and reveals the reality of the war from the Iraqi perspective. -

Adult Fiction Adult Fiction

A Book A Book Inspired by Inspired by Another Another Literary Work Literary Work Adult Fiction Adult Fiction • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • March by Geraldine Brooks • March by Geraldine Brooks • The Master and Margarita • The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov by Mikhail Bulgakov • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits by Mary Jane Hathaway by Mary Jane Hathaway • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Ulysses by James Joyce • Ulysses by James Joyce • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son by Dean Koontz by Dean Koontz • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Fool by Christopher Moore • Fool by Christopher Moore • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Boy, -

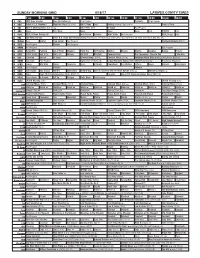

Sunday Morning Grid 6/18/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/18/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Paid Program 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Sailing America’s Cup. (N) Å Track & Field 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid XTERRA Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday 2017 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. The final round of the 2017 U.S. Open tees off. From Erin Hills in Erin, Wis. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Northern Borders (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVY) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Concrete River The Carpenters: Close to You Pavlo Live 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) El Que No Corre Vuela (1982) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. -

{Download PDF} in Odd We Trust Kindle

IN ODD WE TRUST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dean Koontz | 224 pages | 01 Jul 2008 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007236961 | English | London, United Kingdom In Odd We Trust PDF Book Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters. I understand Dean Koontz's interest in experimenting with different story telling formats and loo I like the Odd Thomas character and when I saw this graphic novel was intrigued to see how they approached the story. In Odd We Trust 4. The characters were so far removed from their novel counterparts that Odd was barely more than a boy who walked from scene to scene just to tie the story together and for some reason Sto I don't really have much good to say about this graphic novel. Ian Edginton. It doesn't end like Erin Hunter's graphic books where the books are serialized. The characters were so far removed from their novel counterparts that Odd was barely more than a boy who walked from scene to scene just to tie the story together and for some reason Stormy had been turned into an angry gun- toting maniac. I haven't ever read any Dean Koontz novels before, and I have to say that this does not give me the desire to do so. It was awful. Garth Ennis and Jamie Delano. We use cookies to give you the best online experience. Trisha — Jul 02, Picked this up at a used bookstore, and thought "Huh! I've heard of soul mates and stuff which I can understand it to an extent but in this graphic novel I just couldn't get a sense for it. -

Frankenstein: the Dead Town: a Novel PDF Book

FRANKENSTEIN: THE DEAD TOWN: A NOVEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dean R Koontz | 423 pages | 26 Oct 2012 | Random House USA Inc | 9780553593686 | English | New York, United States Frankenstein: the Dead Town: a Novel PDF Book To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. It syncs automatically with your account and allows you to read online or offline wherever you are. Helios has acquired wealth and power from selling his knowledge to, among others, Adolf Hitler , Joseph Stalin , and the People's Republic of China. Our insipid band of idiots, I mean heroes find weird bits of flesh all over the place, some look almost normal and others have weird shit like extra body parts growing out of them. A member of the New Race. Others fainted. Im still upset that this didn't become a movie or series. A little girl in Las Vegas. Opposed to his activities are a pair of homicide detectives and Frankenstein's original monster , now known as Deucalion. I think they also went a little ape-shit in the first two books, Prodigal Son and City of Night. Michael Richan writes it and there are multiple series that all take place within the one universe. A dark memory is calling out to them. Now the master of suspense delivers an unforgettable novel that is at once a thrilling adventure in itself and a mesmerizing conclusion to his saga of the modern monsters among us. Please follow the detailed Help center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders. I drug this one out because I am going to miss Deucalion! First, there is Deucalion, Helios original creation. -

Guide to the William K

Guide to the William K. Everson Collection George Amberg Memorial Film Study Center Department of Cinema Studies Tisch School of the Arts New York University Descriptive Summary Creator: Everson, William Keith Title: William K. Everson Collection Dates: 1894-1997 Historical/Biographical Note William K. Everson: Selected Bibliography I. Books by Everson Shakespeare in Hollywood. New York: US Information Service, 1957. The Western, From Silents to Cinerama. New York: Orion Press, 1962 (co-authored with George N. Fenin). The American Movie. New York: Atheneum, 1963. The Bad Guys: A Pictorial History of the Movie Villain. New York: Citadel Press, 1964. The Films of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Citadel Press, 1967. The Art of W.C. Fields. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967. A Pictorial History of the Western Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1969. The Films of Hal Roach. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971. The Detective in Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1972. The Western, from Silents to the Seventies. Rev. ed. New York: Grossman, 1973. (Co-authored with George N. Fenin). Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1974. Claudette Colbert. New York: Pyramid Publications, 1976. American Silent Film. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978, Love in the Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1979. More Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1986. The Hollywood Western: 90 Years of Cowboys and Indians, Train Robbers, Sheriffs and Gunslingers, and Assorted Heroes and Desperados. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1992. Hollywood Bedlam: Classic Screwball Comedies. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1994. -

The Parable of the Prodigal Son in the Fiction of Elizabeth Gaskell

THE PARABLE OF THE PRODIGAL SON IN THE FICTION OF ELIZABETH GASKELL Tatsuhiro OHNO A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Letters Department of English Literature College of Arts and Law Graduate School University of Birmingham September 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to analyse Elizabeth Gaskell’s three prodigal short stories—“Lizzie Leigh” (1850), “The Crooked Branch” (1859), and “Crowley Castle” (1863)—with reference to her major works in terms of the biblical parable of the Prodigal Son representing the principal Christian creed of the Plan of Sal- vation. The investigation into the three short stories in addition to her major works discloses the following three main features. First, the recurrent appearance of the Prodigal Son motif—committing sin, repentance, and forgiveness—in her characters’ lives and actions. Second, Gaskell’s change of depicting the prodigal by gradually refraining from inserting hints for its salvation—there are many hints in the first short story, almost none in the second, and few in the third. -

Gothic Representations: History, Literature, and Film Daniel Gould Governors State University

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship All Student Theses Student Theses Fall 2010 Gothic Representations: History, Literature, and Film Daniel Gould Governors State University Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gould, Daniel, "Gothic Representations: History, Literature, and Film" (2010). All Student Theses. 101. http://opus.govst.edu/theses/101 For more information about the academic degree, extended learning, and certificate programs of Governors State University, go to http://www.govst.edu/Academics/Degree_Programs_and_Certifications/ Visit the Governors State English Department This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Student Theses by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 11 GOTHIC REPRESENTATIONS: HISTORY, LITERATURE, AND FILM By Daniel Gould B.A. Western Michigan University, 2004 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts With a Major in English Governors State University University Park, IL 60466 2010 111 AKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are numerous people I need to thank for assisting me in the finalization of Gothic Representations. First and foremost is my wife, Jennifer, who took on many more family responsibilities so I could commit the time and energy necessary to completing this project. Also, my brothers, Jeff and Tim, the two most encouraging people I have ever met. -

The Dystopian World of Blade Runner: an Ecofeminist Perspective

Trumpeter (1997) ISSN: 0832-6193 The Dystopian World of Blade Runner: An Ecofeminist Perspective Mary Jenkins University of Tasmania The Dystopian World of Blade Runner: An Ecofeminist Perspective 2 MARY JENKINS is in the Department of Geography and Envi- ronmental Studies at the University of Tasmania, Hobart, Aus- tralia. The real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands but in seeing with new eyes. - Marcel Proust The science fiction film, Blade Runner, directed by Ridley Scott, first released in 1982 and loosely based on Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?,1 has continued to fascinate film viewers, theorists and critics for more than fifteen years. Writings include Judith B. Kerman's Retrofitting Blade Runner, a collection of academic essays;2 Paul M. Sammon's book on the making of the various versions of the film;3 and an extensive network of publications are available via the World-Wide Web.4 A student colleague has just seen the film for the eighteenth time. The "Director's Cut", released in 1992, is a more satisfying version of the film than earlier releases, mainly because narration is excluded, more mythological ambiguity is introduced (with the inclusion of a scene of a unicorn running through a forest), and the finalé of an escape into nature is removed. In the context of Blade Runner's dystopia such an ending is incredible; for science fiction to succeed there needs to be plausibility within speculation. Since the Director's Cut, Blade Runner seems to have had a phoenix-like resur- gence. -

The Great American Read

A PROGRAMMING GUIDE FOR LIBRARIES | SUMMER 2018 CONTENTS About the Series 3 The List of 100 Books 5 The Episodes 7 Leading Discussions about the Series 9 Lectures 13 Using Film Programs to Explore Books 15 Book Displays 21 Community Reads and Other Reading Programs 23 Hands-on Maker and Craft Programs 25 Hosting a Book Tour 27 Programming for all Ages 31 More Multigenerational Program Ideas 35 Spinoffs and Satires: Fresh Takes on America’s 100 Best-Loved Books 37 Alternate Themes 41 Banned but Beloved 47 Popular versus Classics: Which Books Will Stick Around? 49 Programming and Your Event Calendar 51 Book Settings: A Complete List 55 1 ABOUT the SERIES THE GREAT AMERICAN READ is an eight-part series that explores and celebrates the power of reading, told through the prism of America’s 100 best-loved novels (as chosen in a national survey). It investigates how and why writers create their fictional worlds, how we as readers are affected by these stories, and what these 100 different books have to say about our diverse nation and our shared human experience. The television series features entertaining and informative documentary segments, with compelling testimonials from celebrities, authors, notable Americans, and book lovers across the country. It comprises a two-hour launch episode in which the list of 100 books is revealed, five one-hour theme episodes that examine concepts common to groups of books on the list, and a finale, in which the results are announced of a nationwide vote to choose America’s best-loved novel. The series is the centerpiece of an ambitious multiplatform digital, social, educational, and community outreach campaign, designed to get the country reading and passionately talking about books. -

Congratulations to the 1,000 Young Adult Fiction Entries Moving on to the Second Round of Review

Congratulations to the 1,000 Young Adult Fiction entries moving on to the second round of review Last Name Young Adult Fiction Title Abbott Powerless Absi FrankenPig Acharya Manu in Kishkindha Acherman SkyTrain from Barkerville Ackles Letters to Ryan Ackley Sign Language Acres Discovering the Wind Acuna Prodigal Son Adams Children of Secrecy Afzelius Dream Slayer Aguilar the sea between us Alcorn The Last Telepath Allen The Corporate Genius Allen THE PIRATE'S GAME Allen Thunderstruck!: The Fall of Heracles Allison The Voyage of the Minotaur Alvarez Esperanza Farm Anctil The Midnight Tree Andemeskel Simon Solomon and the Magical Bushman Warrior Anderson Providence, Book One of the Madigan Trilogy Angstadt Tiros Anstead Jessica Saint-Cloud and the Spyglass of the Caribbean Antunes The Pierrot's Love Arnold Why My Love Life Sucks Arp Hurry Back Aseem Don't Mess With My Sister Ashman Together with Silver: The Lupine Prince Atchley Origen of Chaos Athmann Braver Atticus An Early Orange Auerbach Princess Pop Axelsen Brine Ayres Babes in Toon Land B The Seer's Fate Bacal The Mask of Impanis Bailey Vhan Zeely and the Time Prevaricators Baker Foundling Baker Olivia's Ride Baker The Promise Bakke DOT TO DOT Baldwin Spencer Murdoch and the Portals of Erzandor Ball Burning Kathryn Notice © 1996-2010, Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates Page 1 Congratulations to the 1,000 Young Adult Fiction entries moving on to the second round of review Last Name Young Adult Fiction Title Ball SONS of the NEPHILIM: HONOR'S CHOICE Ballard Middle of Nowhere Barker -

El Mito De Frankenstein En El Cine: Transmediación Y Ciencia Ficción (Blade Runner Y 2049)

El mito de Frankenstein en el cine: transmediación y ciencia ficción (Blade Runner y 2049) The Frankenstein Myth in Film: Transmediation and Science Fiction (Blade Runner and 2049) PEDRO JAVIER PARDO Universidad de Salamanca [email protected] ORCID ID: 0000-0001-8347-5738 Resumen: Este trabajo explora la Abstract: This essay explores the presencia de Frankenstein en el cine a presence of Frankenstein in film partir de un marco teórico basado en through a theoretical frame based on los conceptos de transtextualidad y the notions of transtextuality and transescritura. En su primera parte transwriting. The first part is a survey hace un recorrido por las of the series of transmediations which transmediaciones que han convertido have turned the novel into a myth and la novela en un mito, con un doble entails a double aim: in the first place, objetivo: en primer lugar, ilustrar el to illustrate the efficiency of the rendimiento del marco teórico y, en theoretical frame and, in the second segundo lugar, alcanzar una definición place, to reach a definition of the del mito frankensteiniano, que se Frankensteinian myth, which is cifra en la dialéctica creador-criatura anchored in the dialectics between articulada por tres motivos narrativos creator and creature, articulated by y desarrollada en tres mitemas. En la three narrative motifs and expressed segunda parte el artículo se interroga in three mythemes. The second part sobre la presencia de este paradigma probes the presence of this paradigm en el cine de ciencia ficción y, in science fiction and, firstly, it primero, separa género de mito (lo distinguishes between myth and genre que permite establecer grados de (which leaves room for different presencialidad), para luego ocuparse degrees in this presence), so then it del grado máximo (donde el mito se focuses on the highest degree (where hace sentir con su dialéctica the dialectics of myth can be característica), que se ilustra con el detected), which is illustrated by a análisis detallado de Blade Runner y detailed analysis of Blade Runner and 2049.