Sicilian St. Joseph's Tables and Feeding the Poor In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

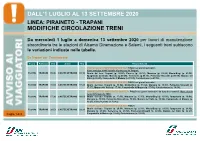

Dall'1 Luglio Al 13 Settembre 2020 Modifiche Circolazione

DALL’1 LUGLIO AL 13 SETTEMBRE 2020 LINEA: PIRAINETO - TRAPANI MODIFICHE CIRCOLAZIONE TRENI Da mercoledì 1 luglio a domenica 13 settembre 2020 per lavori di manutenzione straordinaria tra le stazioni di Alcamo Diramazione e Salemi, i seguenti treni subiscono le variazioni indicate nelle tabelle. Da Trapani per Castelvetrano Treno Partenza Ora Arrivo Ora Provvedimenti CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA202 nei giorni lavorativi. Il bus anticipa di 40’ l’orario di partenza da Trapani. R 26622 TRAPANI 05:46 CASTELVETRANO 07:18 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 05:06), Paceco (p. 05.16), Marausa (p. 05:29) Mozia-Birgi (p. 05.36), Spagnuola (p.05:45), Marsala (p.05:59), Terrenove (p.06.11), Petrosino-Strasatti (p.06:19), Mazara del Vallo (p.06:40), Campobello di Mazara (p.07:01), Castelvetrano (a.07:18). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA218 nei giorni lavorativi. R 26640 TRAPANI 16:04 CASTELVETRANO 17:24 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 16:04), Mozia-Birgi (p. 16:34), Marsala (p. 16:57), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 17:17), Mazara del Vallo (p. 17:38), Campobello di Mazara (p. 17:59), Castelvetrano (a. 18:16). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA220 nei giorni lavorativi da lunedì a venerdì. Non circola venerdì 14 agosto 2020. R 26642 TRAPANI 17:30 CASTELVETRANO 18:53 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 17:30), Marausa (p. 17:53), Mozia-Birgi (p. 18:00), Spagnuola (p. 18:09), Marsala (p. 18:23), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 18:43), Mazara del Vallo (p. 19:04), Campobello di Mazara (p. 19:25), Castelvetrano (a. 19:42). -

Deliberazioni Di G.M. Anno 2015

Deliberazioni di G.M. anno 2015 N. Data Oggetto 1 08.01.2015 Anticipazione somma Economato – 1° trimestre 2015 2 12.01.2015 Rinnovo assicurazione automezzi comunali (responsabilità civile e copertura infortuni conducenti) – Anno 2015 – Autorizzazione a contrattare e assegnazione risorse al Segretario Comunale 3 12.01.2015 Assegnazione risorse al dirigente del 2° settore per la fornitura di abbonamenti per i mesi Gennaio/maggio 2015. 4 19.01.2015 Prosecuzione lavori socialmente utili, bacino a carico del fondo sociale per l’occupazione e formazione – bimestre Gennaio/Febbraio 2015 5 19.01.2015 Assegnazione somme al dirigente 4° settore per servizio di Igiene Ambientale – anno 2015 - 6 19.01.2015 Assegnazione risorse al dirigente del 4° settore tecnico per intervento di manutenzione straordinaria per installazione nuove caldaie autonome e relativa tubazione nell’edificio comunale di Piazza . Fedele – Piano 1° e 2° 7 21.01.2015 Concessione contributo alla Direzione Didattica “G.G.Sinopoli” per l’anno solare 2015. Prenotazione di spesa e assegnazione risorse al dirigente del 2° settore 8 21.01.2015 Proroga contratti LSU prioritari ex L.R. 85/95 a tempo parziale a 24 ore settimanali – anno 2015 – ai sensi dell’art. 4 L.R. 2/2015 9 28.01.2015 Progetto esecutivo per il Piano di investigazione iniziale della discarica dismessa di r.s.u. sita in C.da Scardiulli – Agira – Approvazione amministrativa. 10 28.01.2015 Approvazione schema di Programma Triennale delle Opere Pubbliche relative al triennio 2015/2017 11 28.01.2015 Cantieri di servizio anno -

Design a Database of Italian Vascular Alimurgic Flora (Alimurgita): Preliminary Results

plants Article Design a Database of Italian Vascular Alimurgic Flora (AlimurgITA): Preliminary Results Bruno Paura 1,*, Piera Di Marzio 2 , Giovanni Salerno 3, Elisabetta Brugiapaglia 1 and Annarita Bufano 1 1 Department of Agricultural, Environmental and Food Sciences University of Molise, 86100 Campobasso, Italy; [email protected] (E.B.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Bioscience and Territory, University of Molise, 86090 Pesche, Italy; [email protected] 3 Graduate Department of Environmental Biology, University “La Sapienza”, 00100 Roma, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Despite the large number of data published in Italy on WEPs, there is no database providing a complete knowledge framework. Hence the need to design a database of the Italian alimurgic flora: AlimurgITA. Only strictly alimurgic taxa were chosen, excluding casual alien and cultivated ones. The collected data come from an archive of 358 texts (books and scientific articles) from 1918 to date, chosen with appropriate criteria. For each taxon, the part of the plant used, the method of use, the chorotype, the biological form and the regional distribution in Italy were considered. The 1103 taxa of edible flora already entered in the database equal 13.09% of Italian flora. The most widespread family is that of the Asteraceae (20.22%); the most widely used taxa are Cichorium intybus and Borago officinalis. The not homogeneous regional distribution of WEPs (maximum in the south and minimum in the north) has been interpreted. Texts published reached its peak during the 2001–2010 decade. A database for Italian WEPs is important to have a synthesis and to represent the richness and Citation: Paura, B.; Di Marzio, P.; complexity of this knowledge, also in light of its potential for cultural enhancement, as well as its Salerno, G.; Brugiapaglia, E.; Bufano, applications for the agri-food system. -

V =~======E==S=E==== TRIBUNALE DI PALERMO 1559~ SEZIONE

j v =~=================================E==S=E==== TRIBUNALE DI PALERMO 1559~ SEZIONE UDIENZA 28/10/1993 NU!'1ERO 01' REGISTRO : 8/91 NOTIZIE 01 REATO I!'1PUTAZIONE : O!'1ICIDIO PROC. C/ : GRECO + 12 ============================================= PRESIDENTE dotto Agnello • GIUDUCE dotto SBa. Saguto P. X. Udienza dotto Pignatone Esame del teste , Leonardo Kessina « :2 O , pAJJ>1l.M0 a:: (.()\t'TE D1 ASSISE D1. Z. .t:../.L ..: Deposit~to in CwcellerlO oggt .., ~ 01 NCEll~R\A '" ...-: u.: O ti O O U cj O (f) ESITO UDIENZA: RINVIO ( 29 OTTOBRE1993) Soc. Coop. O.F.T. a r.l PrBside~: Il Presidente! pr81imin~rmGnte,ri18v~ 15595 una necessità di registrare e trascrivere il contenuto della odierna udienza e, a tale SCOPOt è stato convocato per essere nominato perito d'ufficio, il signor Terracciano Saverio, nata a Messina il 13 Settembre 1955, residente ad Ostia. Facciamolo venire avanti. Giuro di bene e fedelmente di procedere all'incarico da lei affidato,. al solo scopo di far conoscere ai giudici la verità! Perito Terracciano Saverjo : Lo giuro! ~:UJ.ente: Il quale, previa prest.astazione del giuramente di accetta Il incarico ... • L'udienza di oggi ha lo scopo di ascoltare le dichiarazioni di Leonardo pfessi na! Facciamolo entrare! Occorre, per favore, disattivare le telecamere ad eccezione di Rai3 e prego tutti di mettere in posizione . di riposo i telefoni cellulari. Lei è Messina Leonardo? Esame di Presidente~ Parli nel « :2 Ripeta le sue generalità. O microfono con chiarp-zza. tI: Hessina LeonardO Sono Messina Leonardo nato a '" San Cataldo... (?) il 22/9/55. Presidente: Il suo t-: • u. O chi è? }(essi na Leonardo LI difensore avvocato a: O .Ligotti! Presidente: Il quale è presente. -

Orari E Sedi Dei Centri Di Vaccinazione Dell'asp Di Caltanissetta

ELENCO CENTRI DI VACCINAZIONE ASP CALTANISSETTA Presidio Altro personale che Giorni e orario di ricevimento Recapito e-mail * Medici Infermieri Comune ( collabora al pubblico Cammarata Giuseppe Bellavia M. Rosa L-M -M -G-V h 8.30-12.30 Caltanissetta Via Cusmano 1 pad. C 0934 506136/137 [email protected] Petix Vincenza ar er Russo Sergio Scuderi Alfia L e G h 15.00-16.30 previo appuntamento L-Mar-Mer-G-V h 8.30-12.30 Milisenna Rosanna Modica Antonina Caltanissetta Via Cusmano 1 pad. B 0934 506135/009 [email protected] Diforti Maria L e G h 15.00 - 16.30 Giugno Sara Iurlaro Maria Antonia Sedute vaccinali per gli adolescenti organizzate previo appuntamento Delia Via S.Pertini 5 0922 826149 [email protected] Virone Mario Rinallo Gioacchino // Lunedì e Mercoledì h 9 -12.00 Sanfilippo Salvatore Sommatino Via A.Moro 76 0922 871833 [email protected] // // Lunedì e Venerdì h 9.00 -12.00 Castellano Paolina L e G ore p.m. previo appuntamento Resuttano Via Circonvallazione 4 0934 673464 [email protected] Accurso Vincenzo Gangi Maria Rita // Previo appuntamento S.Caterina Accurso Vincenzo Fasciano Rosamaria M V h 9.00-12.00 Via Risorgimento 2 0934 671555 [email protected] // ar - Villarmosa Severino Aldo Vincenti Maria L e G ore p.m. previo appuntamento Martedì e Giovedì h 9.00-12.00 Riesi C/da Cicione 0934 923207 [email protected] Drogo Fulvio Di Tavi Gaetano Costanza Giovanna L - G p.m. -

Riepilogo Periodo

Riepilogo periodo: 31/12/2020 - 29/04/2021 Giorni effettivi di vaccinazione Comune di Gagliano Castelferrato (EN) Prot. N.0004568 del 04-05-2021 arrivo Cat14 Cl.1 Fascicolo 113 / Periodo selezionato Centro vaccinale Riepilogo delle vaccinazioni effettuate 31/12/2020 29/04/2021 Tutte Somministrazioni e Totali per Data Vaccinazione e Tipo Vaccino Somministrazioni cumulate per data vaccinazione e proiezione a 10 gg Tipo Vaccino ASTRAZENECA MODERNA PFIZER Totali 70K 1.400 60K 1.200 ate 50K 1.000 ul um c oni i 40K oni az 800 i tr az s tr ni i s 30K m ni 600 i m om S om 20K 400 S 200 10K 0 0K gen 2021 feb 2021 mar 2021 apr 2021 gen 2021 feb 2021 mar 2021 apr 2021 mag 2021 Data Vaccinazione Data Vaccinazione Dosi somministrate % per Vaccino Dosi 1 2 Dose 1 2 Totale Vaccino Somministra % Somministra % Somministra % 3,6K (6,7%) 9,02K zioni zioni zioni (16,79%) ASTRAZENECA 8999 16,76% 17 0,03% 9016 16,79% MODERNA 2225 4,14% 1375 2,56% 3600 6,70% Vaccino 68,22% 31,78% PFIZER 25412 47,32% 15671 29,18% 41083 76,51% PFIZER Comune di Gagliano Castelferrato (EN) Prot. N.0004568 del 04-05-2021 arrivo Cat14 Cl.1 Fascicolo ASTRAZENECA Totale 36636 68,22% 17063 31,78% 53699 100,00% MODERNA 53699 475,21 41,08K (76,51%) 0% 50% 100% Totale somministrazioni Media giornaliera Somministrazioni / Periodo selezionato Centro vaccinazione Somministrazioni per centro di 31/12/2020 29/04/2021 vaccinazione Tutte Somministrazioni per centro vaccinale Somministrazioni per centro vaccinale 2,3K Vaccino ASTRAZENECA MODERNA PFIZER Totale 2,4K (4,46%) (4,28%) Città 1 2 Totale -

Albanian Catholic Bulletin Buletini Katholik Shqiptar

ISSN 0272 -7250 ALBANIAN CATHOLIC BULLETIN PUBLISHED PERIODICALLY BY THE ALBANIAN CATHOLIC INFORMATION CENTER Vol.3, No. 1&2 P.O. BOX 1217, SANTA CLARA, CA 95053, U.S.A. 1982 BULETINI d^M. jpu. &CU& #*- <gP KATHOLIK Mother Teresa's message to all Albanians SHQIPTAR San Francisco, June 4, 1982 ALBANIAN CATHOLIC PUBLISHING COUNCIL: ZEF V. NEKAJ, JAK GARDIN, S.J., PJETER PAL VANI, NDOC KELMENDI, S.J., BAR BULLETIN BARA KAY (Assoc. Editor), PALOK PLAKU, RAYMOND FROST (Assoc. Editor), GJON SINISHTA (Editor), JULIO FERNANDEZ Volume III No.l&2 1982 (Secretary), and LEO GABRIEL NEAL, O.F.M., CONV. (President). In the past our Bulletin (and other material of information, in cluding the book "The Fulfilled Promise" about religious perse This issue has been prepared with the help of: STELLA PILGRIM, TENNANT C. cution in Albania) has been sent free to a considerable number WRIGHT, S.J., DAVE PREVITALE, JAMES of people, institutions and organizations in the U.S. and abroad. TORRENS, S.J., Sr. HENRY JOSEPH and Not affiliated with any Church or other religious or political or DANIEL GERMANN, S.J. ganization, we depend entirely on your donations and gifts. Please help us to continue this apostolate on behalf of the op pressed Albanians. STRANGERS ARE FRIENDS News, articles and photos of general interest, 100-1200 words WE HAVEN'T MET of length, on religious, cultural, historical and political topics about Albania and its people, may be submitted for considera tion. No payments are made for the published material. God knows Please enclose self-addressed envelope for return. -

Liberalia Tu Accusas ! Restituting the Ancient Date of Caesar’S Funus*

LIBERALIA TU ACCUSAS ! RESTITUTING THE ANCIENT DATE OF CAESAR’S FUNUS* Francesco CAROTTA**, Arne EICKENBERG*** Résumé. – Du récit unanime des anciens historiographes il ressort que le funus de Jules César eut lieu le 17 mars 44 av. J.-C. Or la communauté académique moderne prétend presque aussi unanimement que cette date est erronée, sans s’accorder cependant sur une alternative. Dans la littérature scientifique on donne des dates entre le 18 et le 23, et plus précisément le 20 mars, en s’appuyant sur la chronologie avancée par Drumann et Groebe. L’analyse des sources historiques et des évènements qui suivirent l’assassinat de César jusqu’à ses funérailles, prouve que les auteurs anciens ne s’étaient pas trompés, et que Groebe avait reconnu la méprise de Drumann mais avait évité de l’amender. La correction de cette erreur invétérée va permettre de mieux examiner le contexte politique et religieux des funérailles de César. Abstract. – 17 March 44 BCE results from the reports by the ancient historiographers as to the date of Julius Caesar’s funus. However, today’s academic community has consistetly claimed that they were all mistaken, however, an alternative has not been agreed on. Dates between 18 and 23 March have been suggested in scientific literature—mostly 20 March, which is the date based on the chronology supplied by Drumann and Groebe. The analysis of the historical sources and of the events following Caesar’s murder until his funeral proves that the ancient writers were right, and that Groebe had recognized Drumann’s false dating, but avoided to adjust it. -

The Albanian Case in Italy

Palaver Palaver 9 (2020), n. 1, 221-250 e-ISSN 2280-4250 DOI 10.1285/i22804250v9i1p221 http://siba-ese.unisalento.it, © 2020 Università del Salento Majlinda Bregasi Università “Hasan Prishtina”, Pristina The socioeconomic role in linguistic and cultural identity preservation – the Albanian case in Italy Abstract In this article, author explores the impact of ever changing social and economic environment in the preservation of cultural and linguistic identity, with a focus on Albanian community in Italy. Comparisons between first major migration of Albanians to Italy in the XV century and most recent ones in the XX, are drawn, with a detailed study on the use and preservation of native language as main identity trait. This comparison presented a unique case study as the descendants of Arbëresh (first Albanian major migration) came in close contact, in a very specific set of circumstances, with modern Albanians. Conclusions in this article are substantiated by the survey of 85 immigrant families throughout Italy. The Albanian language is considered one of the fundamental elements of Albanian identity. It was the foundation for the rise of the national awareness process during Renaissance. But the situation of Albanian language nowadays in Italy among the second-generation immigrants shows us a fragile identity. Keywords: Language identity; national identity; immigrants; Albanian language; assimilation. 221 Majlinda Bregasi 1. An historical glance There are two basic dialect forms of Albanian, Gheg (which is spoken in most of Albania north of the Shkumbin river, as well as in Montenegro, Kosovo, Serbia, and Macedonia), and Tosk, (which is spoken on the south of the Shkumbin river and into Greece, as well as in traditional Albanian diaspora settlements in Italy, Bulgaria, Greece and Ukraine). -

Road Book Pa 200 2019.Xlsx

Le Strade del Vino - Randonée di Palermo 200 Km. RADUNO: Piazza Verdi ore 6:30 - 8:00 PARTENZA: ore 7:00 – 8:15 Progr. KM PARZ. Km TOT. LOCALITÀ INDICAZIONI 1 0,00 0,00 PALERMO diritto su Via Maqueda 2 0,60 0,60 PALERMO A Dx su Via Vitt. Emanuele / Corso Calatafimi Monreale/SP 69 / Via Palermo / Via Roma (segui Asse 3 5,40 PALERMO/MONREALE 6,00 viario principale/(Via A.Veneziano/Via Pietro Novelli) 4 5,00 11,00 MONREALE Innesto su S.S.186/ Dir. Pioppo 5 6,30 17,30 PIOPPO Continua a DX su S.S.186 - Dir. Partinico 6 13,20 30,50 PARTINICO Rotatoria - a SX su S.S.113 - dir. Alcamo Lascia S.S.113 - a DX dir. Alcamo Centro (C.da 7 14,30 ALCAMO 44,80 Forche/Via Porta Palermo) 8 1,60 46,40 ALCAMO a SX su Corso VI Aprile ALCAMO km.47,00 - CONTROLLO 1 (a SX) - Piazza Ciullo presso Caffè Impero - ore 8:45 -10:52 13 0,65 47,65 ALCAMO Aggirare la piazzetta e proseguire diritto su Corso Dei Mille 14 0,85 48,50 ALCAMO Tenere la DX - proseguire su S.S.119 "Strada del Vino" 15 20,35 68,85 ALCAMO/POGGIOREALE Girare a SX dir. Poggioreale QUADRIVIO - Segui a DX per "Ruderi di Poggioreale" 16 3,75 ALCAMO/POGGIOREALE 72,60 !!! Strada Sconnessa !!! 17 2,60 75,20 !!ATTENZIONE!! STRADA LIEVEMENTE DISSESTATA !!! 18 2,10 77,30 POGGIOREALE Bivio - tenere la DX su SP 27 19 1,40 78,70 POGGIOREALE sul tornante "RUDERI DI POGGIOREALE" 20 0,95 79,65 POGGIOREALE diritto su S.P. -

Deliverable 6.1 Typology of Conflicts in MESMA Case Studies

MESMA Work Package 6 (Governance) Deliverable 6.1 Typology of Conflicts in MESMA case studies Giovanni D’Anna, Tomás Vega Fernández, Carlo Pipitone, Germana Garofalo, Fabio Badalamenti CNR-IAMC Castellammare del Golfo & Mazara del Vallo, Italy Case study report: The Strait of Sicily case study, Sicilian sub-case study A7.6 Case study report: The Strait of Sicily case study, Sicilian sub-case study Basic details of the case study: Initiative Egadi Islands (Isole Egadi )Marine Protected Area, Sicily Description The implementation and management of the Egadi Islands marine protected area (designated under national legislation) and the overlapping cSAC (due to be designated under the Habitats Directive) Objectives Nature conservation / MPAs: Maintaining or restoration to favourable conservation status of conservation features Scale Local (single MPA), ~540 km2 Period covered 1991-2012 Researchers Giovanni D’Anna, Tomás Vega Fernández, Carlo Pipitone, Germana Garofalo, Fabio Badalamenti (Institute for Coastal and Marine Environment (IAMC), National Research Council (CNR)) Researchers’ Natural Science (Environmental Science, Marine Ecology) background Researchers’ role Independent observers in initiative The next 34 pages reproduce the case study report in full, in the format presented by the authors (including original page numbering!). The report should be cited as: D’Anna, G.; Badalamenti, F.; Pipitone, C.; Vega Fernández, T.; Garofalo, G. (2013) WP6 Governance Analysis in the Strait of Sicily. Sub-case study: “Sicily”. A case study report for Work Package 6 of the MESMA project (www.mesma.org). 34pp. A paper on this case study analysis is in preparation for a special issue of Marine Policy. 315 MESMA Work Package 6 WP6 Governance Analysis in the Strait of Sicily Sub-case study: “Sicily” Giovanni D’Anna, Fabio Badalamenti, Carlo Pipitone, Tomás, Vega Fernández, Germana Garofalo Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto per l’Ambiente Marino Costiero Report January 2013 1 1. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

DALL’1 LUGLIO AL 13 SETTEMBRE 2020 LINEA: PIRAINETO - TRAPANI MODIFICHE CIRCOLAZIONE TRENI Da mercoledì 1 luglio a domenica 13 settembre 2020 per lavori di manutenzione straordinaria tra le stazioni di Alcamo Diramazione e Salemi, i seguenti treni subiscono le variazioni indicate nelle tabelle. Da Trapani per Castelvetrano Treno Partenza Ora Arrivo Ora Provvedimenti CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA202 nei giorni lavorativi. Il bus anticipa di 40’ l’orario di partenza da Trapani. R 26622 TRAPANI 05:46 CASTELVETRANO 07:18 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 05:06), Paceco (p. 05.16), Marausa (p. 05:29) Mozia-Birgi (p. 05.36), Spagnuola (p.05:45), Marsala (p.05:59), Terrenove (p.06.11), Petrosino-Strasatti (p.06:19), Mazara del Vallo (p.06:40), Campobello di Mazara (p.07:01), Castelvetrano (a.07:18). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA218 nei giorni lavorativi. R 26640 TRAPANI 16:04 CASTELVETRANO 17:24 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 16:04), Mozia-Birgi (p. 16:34), Marsala (p. 16:57), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 17:17), Mazara del Vallo (p. 17:38), Campobello di Mazara (p. 17:59), Castelvetrano (a. 18:16). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA220 nei giorni lavorativi da lunedì a venerdì. Non circola venerdì 14 agosto 2020. R 26642 TRAPANI 17:30 CASTELVETRANO 18:53 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 17:30), Marausa (p. 17:53), Mozia-Birgi (p. 18:00), Spagnuola (p. 18:09), Marsala (p. 18:23), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 18:43), Mazara del Vallo (p. 19:04), Campobello di Mazara (p. 19:25), Castelvetrano (a. 19:42).