Butte) Reveille 1903-1906

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Timber Depredations in Montana to 1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1967 Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900 Edward Bernie Butcher The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butcher, Edward Bernie, "Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900" (1967). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4709. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4709 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / 7y AN ANALYSIS OF TIMBER DEPREDATIONS IN MONTANA TO 1900 by Edward Bernie Butcher B. S. Eastern Montana College, 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1967 Approved by: (fhe&d j Chairman, Board of Examiners Deaf, Graduate School JU N 1 9 1967 Date UMI Number: EP40173 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP40173 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Clark and Daly - a Personality Analysis

The topper King?: Clark and Daly - A Personality Analysis A Thesis Presented to the Department of History, Carroll College, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors By Michael D. Walsh * \ March 1975 CORETTE LIBRARY CARROI I mi I cr.c 5962 00082 610 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA 596QH SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. 7 rf7ir ....... .................7 ' Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance in my research I wish to thank the staff of the Montana Historical Society Library. I would like to thank my mother who typed this paper and my father who provided the copies. My thanks to Cynthia Rubel and Michael Shields who served as proof readers. I am also grateful to Reverend Eugene Peoples,Ph.D., and Dr. William Lang who read this thesis and offered help ful suggestions. Finally, my thanks to Reverend William Greytak,Ph.D, my director, for h1s criticism, guidance and encouragement which helped me to complete this work. CONTENTS Chapter 1. Their Contemporaries.................................... 1 Chapter 2. History’s Viewpoint ..................................... 13 Chapter 3. Correspondence and Personal Reflections . .................... ....... 24 Bibliography 32 CHAPTER 1 Their Contemporaries In 1809 the territory of Montana was admitted to the Union as the forty-first state, With this act Montana now had to concern herself with the elections of public officials and the selection of a location for the capital. For the next twelve years these political issues would provide the battleground for two men, fighting for supremacy in the state; two men having contributed considerably to the development of Montana (prior to 1889) would now subject her to twelve years of political corruption, William Andrew Clark, a migrant from Pennsylvania, craved the power which would be his if he were to become the senator from Montana. -

![Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4511/hamilton-a-legacy-for-the-bitterroot-valley-an-historical-pageant-drama-of-hamilton-mont-1044511.webp)

Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant- drama of Hamilton, Mont.] Donald William Butler The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Donald William, "Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant-drama of Hamilton, Mont.]" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2505. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2505 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAMILTON A LEGACY FOR THE BITTERROOT VALLEY by DONALD WILLIAM BUTLER B.A. Montana State University, 1949 Presented in partial f-ulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by; / t*-v« ^—— Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School AUG 1 7 1959 Date UMI Number: EP34131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP34131 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

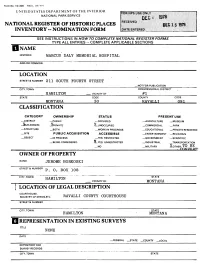

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE til NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN //OW 7~O COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC MARCUS DALY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 211 SOUTH FOURTH STREET —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT HAMILTON __.VICINITY OF #1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE MONTANA 30 RAVALLI 081 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _XuiLDING(S) _?PRIVATE X_UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY X.OTHER:TO BE OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JEROME BORKOSKI STREETS, NUMBER p> Q> g^ ^ C.TY.TOWN HAMILTON STATE __ VICINITY OF MONTANA i LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. RAVALLI COUNTY COURTHOUSE STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE HAMILTON MONTANA REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS NONE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED X.UNALTERED X ORIGINAL SITE —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Marcus Daly Hospital is one of the most impressive structures in the entire Bitterroot Valley. Construction on the structure, considered to b( the most fireproof possible, began in August, 1930. The design was pre pared by H. E. Kirkemo, architect, of Missoula, Montana. -

100Years the Antiquities Act 1906-2006 the National Historic Preservation Act 1966-2006 of Preservation

100years the antiquities act 1906-2006 the national historic preservation act 1966-2006 of preservation photographs by jack e. boucher and jet lowe PillarOF PRESERVATION celebrating four decades of the national historic preservation act “I was dismayed to learn from reading this report that almost half of the 12,000 structures list- ed in the Historic American Buildings Survey of the National Park Service have already been destroyed,” writes Lady Bird Johnson in the foreword to With Heritage So Rich, the call to arms pub- lished in tandem with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Urban renewal seemed unstoppable in the early ’60s. Pennsylvania Avenue, deemed dowdy by President Kennedy during his inaugural parade, was slated for a makeover by modernist architects. “The champions of modern architecture seldom missed an opportunity to ridicule the past,” historian Richard Longstreth wrote in these pages a few years ago, reassessing the era. “Buildings and cities created since the rise of industrial- ization were charged with having nearly ruined the planet. The legacy of one’s parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents was not only visually meaningless and degenerate, but socially and spiritually repres- sive as well.” Against this tide, a generation rose up, giving birth to a populist movement. Here, Common Ground salutes what was saved, and what was lost. Right: The National Archives, along Pennsylvania Avenue. 28 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 29 30 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 FAR LEFT AND BELOW JET LOWE/NPS/HAER, JACK E. BOUCHER/NPS/HAER FAR The National Historic Preservation Act—embracing the full breadth of sites integral to the nation’s story—reflects a dynamic vision of the past and the ingredients that make it matter. -

Southwest MONTANA

visitvisit SouthWest MONTANA 2017 OFFICIAL REGIONAL TRAVEL GUIDE SOUTHWESTMT.COM • 800-879-1159 Powwow (Lisa Wareham) Sawtooth Lake (Chuck Haney) Horses (Michael Flaherty) Bannack State Park (Donnie Sexton) SouthWest MONTANABetween Yellowstone National Park and Glacier National Park lies a landscape that encapsulates the best of what Montana’s about. Here, breathtaking crags pierce the bluest sky you’ve ever seen. Vast flocks of trumpeter swans splash down on the emerald waters of high mountain lakes. Quiet ghost towns beckon you back into history. Lively communities buzz with the welcoming vibe and creative energy of today’s frontier. Whether your passion is snowboarding or golfing, microbrews or monster trout, you’ll find endless riches in Southwest Montana. You’ll also find gems of places to enjoy a hearty meal or rest your head — from friendly roadside diners to lavish Western resorts. We look forward to sharing this Rexford Yaak Eureka Westby GLACIER Whitetail Babb Sweetgrass Four Flaxville NATIONAL Opheim Buttes Fortine Polebridge Sunburst Turner remarkable place with you. Trego St. Mary PARK Loring Whitewater Peerless Scobey Plentywood Lake Cut Bank Troy Apgar McDonald Browning Chinook Medicine Lake Libby West Glacier Columbia Shelby Falls Coram Rudyard Martin City Chester Froid Whitefish East Glacier Galata Havre Fort Hinsdale Saint Hungry Saco Lustre Horse Park Valier Box Belknap Marie Elder Dodson Vandalia Kalispell Essex Agency Heart Butte Malta Culbertson Kila Dupuyer Wolf Marion Bigfork Flathead River Glasgow Nashua Poplar Heron Big Sandy Point Somers Conrad Bainville Noxon Lakeside Rollins Bynum Brady Proctor Swan Lake Fort Fairview Trout Dayton Virgelle Peck Creek Elmo Fort Benton Loma Thompson Big Arm Choteau Landusky Zortman Sidney Falls Hot Springs Polson Lambert Crane Condon Fairfield Great Ronan Vaughn Haugan Falls Savage De Borgia Plains Charlo Augusta CONTENTS Paradise Winifred Bloomfield St. -

S Involvement in Chilean to the Department of History in Candidacy for the Degree of Helena, Montana

CARROLL COLLEGE LAS POLITICAS DEL COBRE: A STUDY OF THE ANACONDA COMPANY’S INVOLVEMENT IN CHILEAN POLITICS 1969-1973 A THESIS SUBMITED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF HONORS GRADUATE BY REBECCA ELLIS HELENA, MONTANA MAY 2003 SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History Dr. Tomas Graman CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................... iii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................. 1 Goals of Study 2. THE PRE-ALLENDE YEARS IN AND OUT OF CHILE.....................5 An examination of political factors operating in Chile prior to the election of Salvador Allende The reaction of the United States Government to the election of Allende The political history of the Anaconda Company The history of the Anaconda Company’s operations in Chile 3. THE PREVENTIVE PERIOD.................................................................19 The Anaconda Company’s efforts to prevent, first the election of Allende and then the nationalization of copper, in conjunction with the United States government The Anaconda Company’s efforts in conjunction with other multinational corporations operating in Chile and facing the threat of nationalization The Company’s powers of influence over Chile as derived from the company’s internal structure 4. THE CONTROL PERIOD......................................................................32 Anaconda’s efforts to gain compensation -

A. Clifford Edwards, Esquire

“WHY DO YOU HURT ME SO?” By: A. Clifford Edwards, Esquire THE INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY OF TRIAL LAWYERS DEAN’S ADDRESS APRIL 7, 2017 SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA A Publication of the International Academy of Trial Lawyers Why Do You Hurt Me So? Good morning Academy! The opinions, express or implied, in this Dean’s Address are solely my own; nothing more, nothing less. President Burbidge; soon-to-be President Noël; fellow officers; my sisters and brothers of our special Academy, guests and my Edwards’ family supporting me here today; Page | 1 Susan – my wife, of such beauty, both of spirit and appearance, my soulmate, as hand-in-hand we experience our lives together; My cherished sons Christopher and John, the proudest achievements of my life; my best friends and only law partners; Their wives, my Daughters-in-law, Kelly and Hollis, who have so enriched and enhanced our Edwards’ family; And, an unexpected bonus that came into my life with her mother Susan over a decade ago when she was just 12, my stepdaughter Alex. Now, we welcome her significant, Patrick Lopach. Then, our little shining family Beacons, – the Edwards’ grandchildren – Ellie Marie, Wright, A.C. and Bella! Now please, you four, sit. Be still! Grandpa’s going to be givin’ a speech. Mother Nature I posit the title of my Dean’s Address – “Why Do You Hurt Me So?” as a troubled query from our wounded Mother of this beautiful and bountiful planet we each absorb every day of our lives. Susan and I share an instilled love for Mother Nature from our Montana upbringings. -

Montana's "Boodlers"

MONTANA'S "BOODLERS": MONTANANS AND THE AFTERMATH OF THE 1899 SENATORIAL SCANDAL by WILLIAM J. YAEGER 'll*- Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors to the Department of History at Carroll College Helena, Montana March, 1983 3 5962 00083 098 Tv This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. Director x fko-. 1 . <1 Reader ^7^/ j>z /are Date ii CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................................................................... iv Chapter I. FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO BRIBERY IN U.S. SENATORIAL ELECTIONS................................................................. 1 II. THE "WAR" THAT LED TO A SCANDAL.............................................. 6 III. THE BUYING OF A LEGISLATURE.................................................... 13 IV. THE CHANDLER HEARING: THE RESIGNATION AND REAPPOINTMENT OF W.A. CLARK................................................... 27 V. AFTERAFFECTS OF MONTANA'S SCANDAL OF 1899............................ 34 VI. CONCLUSIONS..................................................................................... 40 APPENDIX A. THE VALEDICTORY OF SENATOR FRED WHITESIDE........................ 44 B. THE EVERETT BILL......................................................................... 47 SOURCES CONSULTED................................................................................... 51 i i i PREFACE As a newsman, I have had to endure accusations at various times that I (meaning my profession) had fabricated -

A Study of Early Utah-Montana Trade, Transportation, and Communication, 1847-1881

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1959 A Study of Early Utah-Montana Trade, Transportation, and Communication, 1847-1881 L. Kay Edrington Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Edrington, L. Kay, "A Study of Early Utah-Montana Trade, Transportation, and Communication, 1847-1881" (1959). Theses and Dissertations. 4662. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4662 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A STUDY OF EARLY UTAH-MONTANA TRADE TRANSPORTATION, AND COMMUNICATION 1847-1881 A Thesis presented to the department of History Brigham young university provo, Utah in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of science by L. Kay Edrington June, 1959 This thesis, by L. Kay Edrington, is accepted In its present form by the Department of History of Brigham young University as Satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Science. May 9, 1959 lywrnttt^w-^jmrnmr^^^^ The writer wishes to express appreciation to a few of those who made this thesis possible. Special acknowledge ments are due: Dr. leRoy R. Hafen, Chairman, Graduate Committee. Dr. Keith Melville, Committee member. Staffs of; History Department, Brigham young university. Brigham young university library. L.D.S. Church Historian's office. Utah Historical Society, Salt lake City. -

Citizens United, Caperton, and the War of the Copper Kings Larry Howell Alexander Blewett I I School of Law at the University of Montana, [email protected]

Alexander Blewett III School of Law at the University of Montana The Scholarly Forum @ Montana Law Faculty Law Review Articles Faculty Publications 2012 Once Upon a Time in the West: Citizens United, Caperton, and the War of the Copper Kings Larry Howell Alexander Blewett I I School of Law at the University of Montana, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.umt.edu/faculty_lawreviews Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Larry Howell, Once Upon a Time in the West: Citizens United, Caperton, and the War of the Copper Kings , 73 Mont. L. Rev. 25 (2012), Available at: http://scholarship.law.umt.edu/faculty_lawreviews/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at The choS larly Forum @ Montana Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Law Review Articles by an authorized administrator of The choS larly Forum @ Montana Law. ARTICLES ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST: CITIZENS UNITED, CAPERTON, AND THE WAR OF THE COPPER KINGS Larry Howell* He is said to have bought legislaturesand judges as other men buy food and raiment. By his example he has so excused and so sweetened corruption that in Montana it no longer has an offensive smell. -Mark Twain' [T]he Copper Kings are a long time gone to their tombs. -District Judge Jeffrey Sherlock 2 I. INTRODUCTION Recognized by even its strong supporters as "one of the most divisive decisions" by the United States Supreme Court in years,3 Citizens United v. * Associate Professor, The University of Montana School of Law. -

Montana Freemason

Montana Freemason Feburary 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Montana Freemason February 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Th e Montana Freemason is an offi cial publication of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Montana. Unless otherwise noted,articles in this publication express only the private opinion or assertion of the writer, and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the Grand Lodge. Th e jurisdiction speaks only through the Grand Master and the Executive Board when attested to as offi cial, in writing, by the Grand Secretary. Th e Editorial staff invites contributions in the form of informative articles, reports, news and other timely Subscription - the Montana Freemason Magazine information (of about 350 to 1000 words in length) is provided to all members of the Grand Lodge that broadly relate to general Masonry. Submissions A.F.&A.M. of Montana. Please direct all articles and must be typed or preferably provided in MSWord correspondence to : format, and all photographs or images sent as a .JPG fi le. Only original or digital photographs or graphics Reid Gardiner, Editor that support the submission are accepted. Th e Montana Freemason Magazine PO Box 1158 All material is copyrighted and is the property of Helena, MT 59624-1158 the Grand Lodge of Montana and the authors. [email protected] (406) 442-7774 Deadline for next submission of articles for the next edition is March 30, 2013. Articles submitted should be typed, double spaced and spell checked. Articles are subject to editing and Peer Review. No compensation is permitted for any article or photographs, or other materials submitted for publication.