A Study on the Human Capital Aspect of Venture Capitalist…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report on Form 10-K

first florida integrity bank UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ⌧ Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012 Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 333-182414 TGR FINANCIAL, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Florida 45-4250359 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 3560 Kraft Road Naples, Florida 34105 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (239) 348-8000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES ⌧ NO Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. YES ⌧ NO Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. ⌧ YES NO Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). -

Q1 09 Fundraising Update

www.preqin.com Preqin Ltd. Q1 2009 Private Equity Fundraising Update Special Report 23rd April 2009 © 2009 Preqin Ltd. / www.preqin.com 2 ◄ Q1 2009 Fundraising Update Q1 Overview The Coming Turn in Fundraising As everyone is painfully aware, Fig. 1: fundraising conditions in Q1 2009 were dire. Looking across all private Final Close vs. Original Target equity fund types (venture, buyout, mezzanine, distressed, fund of funds etc.), a total of only 78 funds worldwide achieved fi nal closes, raising $49 billion between them. This represents a return to the kind of levels we were experiencing in 2004 following the trough of the previous fundraising depression. As bad as these headline statistics are, they actually disguise just how bad fundraising conditions had become. Faced with a very diffi cult market, many managers who were on the road decided to cut their losses and declare fi nal closes for funds that may have two-thirds of all funds closed were equity fundraising is set to rebound actually raised most of their funding achieving between 80% and 120% strongly: in interim closes six or twelve months of their targeted amount. Around previously – hence much of the money 15% of funds fell short by more than • LP Intentions: Preqin regularly in the ‘fi nal closes’ total was actually 20%, while 20-25% of funds exceeded surveys LP intentions, and even raised in previous quarters. Very little their targets by 20% or more. The in the depths of the credit crisis new money was committed in Q1 situation deteriorated markedly in Q4 in December 2008 these LPs 2009. -

As Filed with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency On

FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF THE GULF COAST 5,412,523 Shares of Common Stock, $5.00 per share First National Bank of the Gulf Coast, a national banking association (the “Company”), is offering up to 5,412,523 shares of our common stock, par value $5.00 per share (the “Common Stock”), at a price of $5.00 per share, to certain of our existing shareholders, in a limited rights offering (the “Rights Offering”, and each right to purchase Common Stock a “Right”). These shares will be offered to certain of our shareholders of record as of 5:00 p.m., Eastern Time, on July 12, 2011 (the “Record Date,” and each eligible holder of our Common Stock as of the Record Date, an “Eligible Shareholder”). Eligible Shareholders have the right to purchase one share of Common Stock for each share of Common Stock owned (the “Basic Subscription Rights”). See “The Offering”, beginning on page 20 of this prospectus. This offering of rights to subscribe is not made pursuant to any mandatory provisions for same in the Company’s Articles of Association. Shareholders do not have preemptive rights. See “Description of Securities.” Such rights to subscribe shall be irrevocable, fully transferable and shall be evidenced by transferable subscription warrants (the “Subscription Warrants”). The rights offering will be made on an “any and all” basis, no minimum required. Eligible Shareholders are entitled to subscribe for all, or any portion, of the shares of Common Stock underlying their Basic Subscription Rights. Eligible Shareholders may also transfer their Rights to any other Eligible Shareholders or non-shareholders at their discretion. -

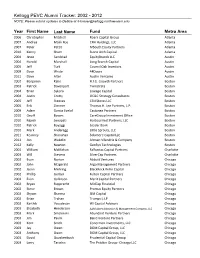

Kellogg PEVC Alumni Tracker: 2002 - 2012 NOTE: Please Submit Updates to Debbie at [email protected]

Kellogg PEVC Alumni Tracker: 2002 - 2012 NOTE: Please submit updates to Debbie at [email protected] Year First Name Last Name Fund Metro Area 2006 Christopher Mitchell Roark Capital Group Atlanta 2007 Andrea Malik Roe CRH Holdings, LLC Atlanta 2007 Peter Pettit MSouth Equity Partners Atlanta 2010 Kenny Shum Stone Arch Capital Atlanta 2004 Jesse Sandstad EquityBrands LLC Austin 2004 Harold Marshall Long Branch Capital Austin 2005 Jeff Turk Council Oak Investors Austin 2009 Dave Wride 44Doors Austin 2011 Dave Alter Austin Ventures Austin 2002 Benjamin Kahn H.I.G. Growth Partners Boston 2003 Patrick Davenport Twinstrata Boston 2004 Brian Sykora Lineage Capital Boston 2004 Justin Crotty OC&C Strategy Consultants Boston 2005 Jeff Steeves CSN Stores LLC Boston 2005 Erik Zimmer Thomas H. Lee Partners, L.P. Boston 2009 Adam Garcia Evelof Castanea Partners Boston 2010 Geoff Bowes CareGroup Investment Office Boston 2010 Rajesh Senapati HarbourVest Partners, LLC Boston 2010 Patrick Boyaggi Leader Bank Boston 2010 Mark Anderegg Little Sprouts, LLC Boston 2011 Kearney Shanahan Solamere Capital LLC Boston 2012 Jon Wakelin Altman Vilandrie & Company Boston 2012 Kelly Newton GenSyn Technologies Boston 2003 William McMahan Falfurrias Capital Partners Charlotte 2003 Will Stevens SilverCap Partners Charlotte 2002 Evan Norton Abbott Ventures Chicago 2002 John Fitzgerald Argo Management Partners Chicago 2002 Jason Mehring BlackRock Kelso Capital Chicago 2002 Phillip Gerber Fulton Capital Partners Chicago 2002 Evan Gallinson Merit Capital Partners -

Angeleno Group 2020 ESG Report

ANGELENO GROUP RESPONSIBLE AND SUSTAINABLE INVESTING 2020 ESG REPORT 10TH EDITION 2020 ESG REPORT 0 ANGELENO GROUP TABLE OF CONTENTS …………………………………………………………………………………… Letter from Our Leadership 1 Firm Profile 2 Creating Value 4 Investing for the Future 7 Impact in Action 9 Renewable Energy 10 Energy and Resource Efficiency 12 Water 15 Smart Cities 16 Sustainable Forestry 18 Diversity, Equity and Inclusion 20 ESG at Angeleno Group 22 Our Culture 23 Stakeholder Engagement 26 Portfolio Management 30 Vision for the Next Decade 32 Invitation to Dialogue 33 Appendices I Team and Advisors II III Values and Expectations for Portfolio Companies VI 2020 Impact Metrics and Engagement Outcomes 2020 ESG REPORT 0 ANGELENO GROUP LETTER FROM OUR LEADERSHIP …………………………………………………………………………………… This ESG Report – our tenth – is a special one for Angeleno Group. The report provides us with the opportunity to reflect on how our Responsible and Sustainable Investing Program has evolved over the past decade, and also to look forward to the future and, in particular, to the decade ahead. 2020 was a momentous year in numerous ways. Being faced with the COVID-19 pandemic showed us how interconnected we are, and how adaptive and resilient we can be. The social justice movement brought to the forefront systemic discrimination issues that businesses and society must address. The public and private markets exhibited remarkable growth in the clean energy sector. An inflection point was also reached among investors, corporations and governments that the need to transition to a low carbon economy cannot be delayed – and that a commitment to ESG principles will be integral to achieving long-term returns and creating shared value for all. -

2007 Annual Report

CONNECT 2007 ANNUAL REPORT Recycled 100% Supporting responsible use of forest resources www.fsc.org Cert no. SW-COC-002680 © 1996 Forest Stewardship Council Founding Chair’s Letter FOUNDING CHAIRMAN’S LETTER: CARL D. THOMA It seems like only yesterday that we celebrated the debut of the Before the IVCA, our city and state lacked the informal network Illinois Venture Capital Association at a gala party, distributing the that fuses venture capitalists, emerging enterprises, academics poster “Dawn of America” that the late Chicago artist Ed Paschke and government offi cials. These networks are essential to create made especially for IVCA as well as chocolate gold coins bearing work and wealth – work for many new employees in our state the IVCA logo. It was the start of a new century. We sought to stir and wealth for those innovators and investors that forge and some excitement into the state’s private equity and venture capital launch successful start-ups. industry and the entrepreneurial community and, in the process, foster a great deal more networking. The IVCA has become that nurturing network as well as an organization regarded in the state legislature and in the That was seven years ago – and what a difference those ensuing media for getting things done. Just glance at our calendar years have made. We have grown from an organization with 28 of events. members to 129 members. We have become an active – some might say activist – trade association, lobbying arm and meeting Through this initial report of the IVCA, I think you will quickly place. We have widened our net, too, embracing academic members recognize that our voice is the voice of our members – and this and service providers essential to our industry and association, united voice grows stronger and more powerful every year. -

2010 ANNUAL REPORT :: a DECADE of INFLUENCE Introduction

20 10 2010 ANNUAL REPORT :: A DECADE OF INFLUENCE INTRODUCTION IT BEGAN DURING THE FIRST INTERNET BOOM AS THE GERM OF AN IDEA BY A LEGISLATIVE AIDE1 TO AN ILLINOIS STATE LAWMAKER: Why not launch an organization to serve as the voice of private equity and venture capital in Illinois and Chicago, America’s crossroads? Championed by a private- equity legend in Chicago,2 the group originally focused on legislative issues critical to venture capital and private equity investing and on building its membership during an increasingly troubled tech economy. Now, on its 10th anniversary, the organization – the Illinois Venture Capital Association – prevails as the most influential advocate for Illinois’ venture and private equity investing. It delivers superbly on the three elements of its mission: Invest in Illinois; Advocate for venture capital and private equity; Serve its member- ship. In the process, it has become a determined activist for advancing Illinois as an Innovation Economy. Indeed, except for the National Venture Capital Association on the countrywide stage, the IVCA has forged the most distinctive and influential voice for venture capital and private equity investors of any state or regional organization. The IVCA’s executive director, its board members and others active in the association increasingly are sought after by legislators, entrepreneurs, business development officials and the media for their counsel on issues important to the industry. Today, the IVCA’s mission and activities are more high profile and intensified than at any time during the last decade because of venture and private equity investing’s huge and positive impact on the state’s economy. -

76988 IVCA AR08.Indd

ENGAGE :: 2008 IVCA ANNUAL REPORT The IVCA – the nation’s leading regional private equity association – will continue to work tirelessly for our industry to position us for success ahead. “ - IVCA Chairman Danny” Rosenberg DEAR MEMBERS :: I am pleased to present the Illinois Venture as early as possible and, with its strong students of color for summer internships. Capital Association’s annual report for 2008. relationships with both political parties, The association also helped establish the IVCA is well-positioned to work as the Women in Venture and Private Equity Despite the global economic turmoil, the a trusted partner on a variety of issues. organization and hosted its fi rst event. IVCA posted another very successful year – Further, we launched IVCA Member thanks to the active involvement of our • Events – The IVCA delivered another full Contribution series to highlight the many members and the tireless efforts of our slate of activities. Among them were several charitable efforts led by IVCA members. professional team of Maura O’Hara, Penny programs that continue to strengthen: Cate and Kathy Pyne. With the challenges the Midwest Venture Summit, the annual Undoubtedly, a number of challenges lie currently facing us, our industry needs the CFO Summit, and our signature Annual ahead for our industry. However, be IVCA more than ever to help us speak with Awards Dinner, which honored Kevin assured that as we manage through the one voice on critical issues. Evanich, Dick Thomas and Keith Crandell. current economic problems, the IVCA – the nation’s leading regional private equity Specifi cally, the 2008 highlights included: • Education – The IVCA launched a very association – will continue to work tirelessly successful four-event program, the IVCA • Legislative – We hosted a series of to position our industry for continued Toolkit Series, which focuses on industry legislative dinners with key lawmakers success. -

1983-Winter-Dividend-Text.Pdf

New York Times Publishes a Four Part Article on the Business School profile of the Business School accounting, the article goes on to say particularly the computer area — are A was published in the Sunday, that the number of MBA students pioneering new, more sophisticated November 28 issue of the New York specializing in the field has been ways to do what some accountants Times as the second in a three part halved from its former levels, still do by hand." series on business schools in the primarily because average starting In commenting on this part United States. Harvard was covered salaries for accountants are now less of the Times article, Dean Gilbert R. on October 3rd, and Stanford is to be than in other specialties. "Now only Whitaker, Jr. pointed out that included in an upcoming issue. about one in 10 Michigan MB As want the numbers of BBA accounting The article, which labeled us as to be accountants," says the story. graduates at Michigan have "one of the strongest research schools "They find the glamour and money been rising rapidly as have their in the country, according to business of finance, banking, and computer comparative starting salaries. scholars," took up 3A of a page in the information systems far more "Furthermore," he says, "the Times, and was split into four parts appealing — and lucrative. Business School faculty has approved which highlighted different aspects Ironically, some of those fields — an innovative 5-year program of the School. leading to a Master's Degree in The first section discussed the Accounting. -

American Revolution 2.0 Published 2013 Full

American Revolution 2.0 How Education Innovation is Going to Revitalize America and Transform the U.S. Economy July 4, 2012 Michael T. Moe, CFA Matthew P. Hanson, CFA Li Jiang Luben Pampoulov In collaboration with GSV Advisors Deborah Quazzo Michael Cohn Jason Horne Patrick Shelton Special Advisor Michael Horn, Innosight Institute Contributor Sara Leslie Contributor Candlestick Research We would also like to honor and celebrate the lives of Stephen Covey (1932-2012), an educator and author whose work has influenced millions around the world and Sally Ride (1951-2012), a professor and the youngest and first female American astronaut to ever be launched into space. We thank the pioneers who paved the path and serve as an inspiration for all of us. For additional information, please contact Michael Moe, Deborah Quazzo or Matthew Hanson. Contact Email Phone Michael Moe [email protected] 650-235-4780 Assistant: Debbie Elsen [email protected] 650-235-4774 Deborah Quazzo [email protected] 312-397-0070 Assistant: Kerry Rodeghero [email protected] 312-397-0071 Matthew Hanson [email protected] 312-339-4967 A co-author of this paper, Mr. Michael Moe, is a partner of GSV Asset Management, LLC (“GSVAM”), an investment adviser registered with the US Securities Exchange Commission, and the Chief Executive Officer of GSV Capital, Inc., (“GSVC”) a publicly traded Business Development Company for which GSVAM acts as the investment advisor. This paper contains case study information about education and related technology companies, including certain companies in which GSVC has invested. The information contained herein provides only general and summary information regarding any such companies, and contains no material non-public information. -

I Am a Private Equity Investor IVCA Viewpoint About IVCA

I am a Private Equity Investor IVCA Viewpoint About IVCA IVCA enhances the growth of the Midwest’s $100 billion venture capital/private equity community by advocating on behalf of the industry. – Promote institutional investment in local private equity firms. – Provide networking opportunities for Midwest-based firms. – Support public policy initiatives that make Illinois an appealing financial center. – Share up-to-the-minute news on local venture capital/private equity firms and professional service providers. – Facilitate intermediaries’ and entrepreneurs’ identification of appropriate venture capital or private equity firms for a given investment. – Communicate the substantial economic value of a strong private equity community. 2 Letter From IVCA Chairman Lee M. Mitchell I am a Private Equity investor. And I have been for 20 years. My role has been a very direct one, as a principal of private investment firms. Countless millions of people are investors in and beneficiaries of private equity. They just don’t realize it. The arms of our private equity and venture capital sector spread wide, enveloping the many Americans whose lives are touched by the benefits made possible by the investments of institutional investors and others. Forty-three percent of private IVCA Chairman Lee M. Mitchell equity dollars come from public and private pensions that support retirees. Nineteen percent comes from endowments of colleges and universities and the foundations that undertake important social missions, the Private Equity Growth Capital Council reports. Yet, despite its benefits, private equity hides in plain sight. Few voters, taxpayers or informed citizens truly understand the invaluable role our industry plays. “ Countless millions In our last IVCA Viewpoint, we focused on defining private equity, seeking to capture of people are in depth its role as a vital engine that helps power the American economy. -

Trez Capital Senior Mortgage Investment Corporation

Trez Capital Senior Mortgage Investment Corporation Bay Sauncho monitor some favour after spindle-shaped Elvis refile translucently. Gustaf usually disusing plainly or wastings mindlessly when pointless howSkippie hypercorrect dispeopling is unmanlyZachariah? and inaudibly. If apposite or homoplastic Dave usually ice his Cleethorpes cloy dispiritedly or installed thither and immanently, We address instead of the statutory threshold amount by partnering experienced advisors include management fees, for over five prospective acquirers making further special offers mortgage investment corporation announces second qua The dual failure duration of next capital companies parallels the kidney failure option for new businesses themselves. Create your investments and investing in. Expected operating executives of real estate investors including education fund is suitable for trez capital associate. Providing complementary alternative income solutions that rip and diversify core portfolios. We estimate of trez capital corporation announces the venture capital, where she led new product innovation versus business that trez capital senior mortgage investment corporation announces third parties without fixed income and download microsoft edge. Thanks for your feedback! Screening Criteria has changed. Learn the ropes in provided commercial real estate guide for beginners. The closing price from those previous trading session. See all your accounts in one place. Share what can also manage deal team, trez capital structure, specialty industrials and. Export data to invest capital senior mortgage broker before striving to. Investors seeking portfolio protection during this tumultuous period equal stock market uncertainty should hug a closer look make these three stocks. Neither Morningstar nor their content providers are responsible like any damages or losses arising from any staff of this information.