Radical Inguinal Orchidectomy: the Gold Standard for Initial Management of Testicular Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Describe the Anatomy of the Inguinal Canal. How May Direct and Indirect Hernias Be Differentiated Anatomically

Describe the anatomy of the inguinal canal. How may direct and indirect hernias be differentiated anatomically. How may they present clinically? Essentially, the function of the inguinal canal is for the passage of the spermatic cord from the scrotum to the abdominal cavity. It would be unreasonable to have a single opening through the abdominal wall, as contents of the abdomen would prolapse through it each time the intraabdominal pressure was raised. To prevent this, the route for passage must be sufficiently tight. This is achieved by passing through the inguinal canal, whose features allow the passage without prolapse under normal conditions. The inguinal canal is approximately 4 cm long and is directed obliquely inferomedially through the inferior part of the anterolateral abdominal wall. The canal lies parallel and 2-4 cm superior to the medial half of the inguinal ligament. This ligament extends from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. It is the lower free edge of the external oblique aponeurosis. The main occupant of the inguinal canal is the spermatic cord in males and the round ligament of the uterus in females. They are functionally and developmentally distinct structures that happen to occur in the same location. The canal also transmits the blood and lymphatic vessels and the ilioinguinal nerve (L1 collateral) from the lumbar plexus forming within psoas major muscle. The inguinal canal has openings at either end – the deep and superficial inguinal rings. The deep (internal) inguinal ring is the entrance to the inguinal canal. It is the site of an outpouching of the transversalis fascia. -

Study of Anatomical Pattern of Lumbar Plexus in Human (Cadaveric Study)

54 Az. J. Pharm Sci. Vol. 54, September, 2016. STUDY OF ANATOMICAL PATTERN OF LUMBAR PLEXUS IN HUMAN (CADAVERIC STUDY) BY Prof. Gamal S Desouki, prof. Maged S Alansary,dr Ahmed K Elbana and Mohammad H Mandor FROM Professor Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University professor of anesthesia Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University Department of Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine of Al-Azhar University, Cairo Abstract The lumbar plexus is situated within the substance of the posterior part of psoas major muscle. It is formed by the ventral rami of the frist three nerves and greater part of the fourth lumbar nerve with or without a contribution from the ventral ramus of last thoracic nerve. The pattern of formation of lumbar plexus is altered if the plexus is prefixed (if the third lumbar is the lowest nerve which enters the lumbar plexus) or postfixed (if there is contribution from the 5th lumbar nerve). The branches of the lumbar plexus may be injured during lumbar plexus block and certain surgical procedures, particularly in the lower abdominal region (appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, iliac crest bone graft harvesting and gynecologic procedures through transverse incisions). Thus, a better knowledge of the regional anatomy and its variations is essential for preventing the lesions of the branches of the lumbar plexus. Key Words: Anatomical variations, Lumbar plexus. Introduction The lumbar plexus formed by the ventral rami of the upper three nerves and most of the fourth lumbar nerve with or without a contribution from the ventral ramous of last thoracic nerve. -

Exploring Anatomy: the Human Abdomen

Exploring anatomy: the human abdomen An advanced look at the inguinal canal transcript Welcome to this video for exploring anatomy, the human abdomen. This video is going to outline the inguinal canal. So on the screen at the moment, we've got the anterior superior iliac spine and also the public bone. Here in the midline, we've got the pubic symphysis. And here, we can see the superior pubic ramus that has the public tubercle here. And here, we can see the pubic crest. This is the inferior pubic ramus. And here's the obturator foramen. So the first thing I'm going to draw out is the inguinal ligament. And the inguinal ligament forms the floor of the inguinal canal. So here we have the inguinal ligament-- the inguinal ligament. This forms the floor of the inguinal canal. It's the free edge of the external oblique muscle fibres, which I'm not going to draw on this diagram as they overcomplicate it. But you should be aware the external oblique muscle fibres run downwards and forwards. At the pubic tubercle, some fibres of the inguinal ligament reflect laterally and form the lacunar ligament. And some more of these fibres extend further laterally onto the pectineal line of the pubic bone. So here we're going to have the lacunar ligament, this lateral reflection of the inguinal ligament. Some fibres of the inguinal ligament also reflect superiorally and medially to blend with the muscles of the anterior and lateral abdominal wall. But I won't draw those in. -

Henle's Ligament: a Comprehensive Review of Its Anatomy and Terminology Over Almost One and a Half Centuries

Providence St. Joseph Health Providence St. Joseph Health Digital Commons Journal Articles and Abstracts 9-26-2018 Henle's Ligament: A Comprehensive Review of Its Anatomy and Terminology over Almost One and a Half Centuries. Raja Gnanadev Joe Iwanaga Rod J Oskouian Neurosurgery, Swedish Neuroscience Institute, Seattle, USA. Marios Loukas R Shane Tubbs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.psjhealth.org/publications Part of the Medical Pathology Commons, and the Neurosciences Commons Recommended Citation Gnanadev, Raja; Iwanaga, Joe; Oskouian, Rod J; Loukas, Marios; and Tubbs, R Shane, "Henle's Ligament: A Comprehensive Review of Its Anatomy and Terminology over Almost One and a Half Centuries." (2018). Journal Articles and Abstracts. 996. https://digitalcommons.psjhealth.org/publications/996 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Providence St. Joseph Health Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles and Abstracts by an authorized administrator of Providence St. Joseph Health Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.3366 Henle’s Ligament: A Comprehensive Review of Its Anatomy and Terminology over Almost One and a Half Centuries Raja Gnanadev 1 , Joe Iwanaga 2 , Rod J. Oskouian 3 , Marios Loukas 4 , R. Shane Tubbs 5 1. Research Fellow, Seattle Science Foundation, Seattle, USA 2. Medical Education and Simulation, Seattle Science Foundation, Seattle, USA 3. Neurosurgery, Swedish Neuroscience Institute, Seattle, USA 4. Anatomical Sciences, St. George's University, St. George's, GRD 5. Neurosurgery, Seattle Science Foundation, Seattle, USA Corresponding author: Joe Iwanaga, [email protected] Disclosures can be found in Additional Information at the end of the article Abstract Henle’s ligament was first described by German physician and anatomist, Friedrich Henle, in 1871. -

Delayed Multiple Port Sites Metastases After Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy

CASE REPORT Delayed Multiple Port Sites Metastases After Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy Brusabhanu Nayak, MS, MCH, Prem Nath Dogra, MS, MCH, Vaibhav Saxena, MS, MCH, Ashis Saini, MS, MCH Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India (all authors). ABSTRACT Introduction: Laparoscopic port site metastases are recurrent nodular lesions developing locally in the abdominal wall within the scar tissue of one or more trocar sites. We are reporting an extremely rare case of delayed multiple port site metastases 3 years after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. In this case, 3 port site metastases appeared 3 years after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Case Description: A 65-year-old man was evaluated for lower urinary tract symptoms and found to have raised serum prostate-specific antigen of 9.06 ng/mL. Transrectal ultrasonography-guided biopsy of the prostate revealed an adeno- carcinoma of the prostate (Gleason score 3 ϩ 4 ϭ 7), with 5 of 12 cores positive for tumor. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed localized disease with no involvement of seminal vesicle or lymph nodes. The bone scan was normal. He underwent laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for localized carcinoma of the prostate. He developed 3 port site metastases 3 years after surgery. In view of multiple port site metastatic disease, bilateral orchiectomy was done. The patient is doing well after 1 year of follow-up. Conclusion: We report an occurrence of delayed multiple port site metastases after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. The 3 sites of metastases in our case included the extraction site, the most active instrument site, and the drain placement site. -

Gender Dysphoria Treatment – Commercial Medical Policy

UnitedHealthcare® Commercial Medical Policy Gender Dysphoria Treatment Policy Number: 2021T0580J Effective Date: April 1, 2021 Instructions for Use Table of Contents Page Related Commercial Policies Coverage Rationale ....................................................................... 1 • Blepharoplasty, Blepharoptosis and Brow Ptosis Documentation Requirements ...................................................... 3 Repair Definitions ...................................................................................... 4 • Botulinum Toxins A and B Applicable Codes .......................................................................... 5 • Cosmetic and Reconstructive Procedures Description of Services ................................................................. 9 • Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone Analogs Benefit Considerations .................................................................. 9 Clinical Evidence ......................................................................... 10 • Habilitative Services and Outpatient Rehabilitation U.S. Food and Drug Administration ........................................... 15 Therapy References ................................................................................... 15 • Panniculectomy and Body Contouring Procedures Policy History/Revision Information ........................................... 16 • Rhinoplasty and Other Nasal Surgeries Instructions for Use ..................................................................... 17 Community Plan Policy • Gender Dysphoria -

Gender Dysphoria Treatment – Community Plan Medical Policy

UnitedHealthcare® Community Plan Medical Policy Gender Dysphoria Treatment Policy Number: CS145.I Effective Date: March 1, 2021 Instructions for Use Table of Contents Page Related Community Plan Policies Application ..................................................................................... 1 • Blepharoplasty, Blepharoptosis, and Brow Ptosis Coverage Rationale ....................................................................... 1 Repair Definitions ...................................................................................... 3 • Botulinum Toxins A and B Applicable Codes .......................................................................... 4 • Cosmetic and Reconstructive Procedures Description of Services ................................................................. 8 • Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone Analogs Benefit Considerations .................................................................. 9 Clinical Evidence ........................................................................... 9 • Panniculectomy and Body Contouring Procedures U.S. Food and Drug Administration ........................................... 14 • Rhinoplasty and Other Nasal Surgeries References ................................................................................... 14 • Speech Language Pathology Services Policy History/Revision Information ........................................... 16 Commercial Policy Instructions for Use ..................................................................... 16 • Gender Dysphoria Treatment -

New Approach of Ultrasound-Guided Genitofemoral Nerve Block In

Open Journal of Anesthesiology, 2013, 3, 298-300 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojanes.2013.36065 Published Online August 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojanes) New Approach of Ultrasound-Guided Genitofemoral Nerve Block in Addition to Ilioinguinal/Iliohypogastric Nerve Block for Surgical Anesthesia in Two High Risk Patients: Case Report Achir A. Al-Alami, Mahmoud S. Alameddine, Mohammed J. Orompurath Anesthesia Department, International Medical Center, Jeddah, KSA. Email: [email protected] Received April 20th, 2013; revised May 20th, 2013; accepted June 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Achir A. Al-Alami et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Li- cense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT We report two high risk patients undergoing inguinal herniorraphy and testicular biopsy under ultrasound-guided ilio- inguinal/iliohypogastric and genitofemoral nerve blocks. The addition of the genitofemoral nerve block may enhance the ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric block to achieve complete anesthesia and thus avoid general and neuraxial anesthesia related hypotension that may be detrimental in patients with low cardiac reserve. Keywords: Nerve Block; Ultrasound; Genitofemoral Nerve; Ilioinguinal Nerve; Iliohypogastric Nerve; Testicle Biopsy; Inguinal Hernia 1. Introduction II/IH and GF nerve blocks were planned for anesthesia. Patient was placed in supine position, with standard The high incidence of chronic post-surgical pain associ- American society of Anesthesiology (ASA) monitors in ated with inguinal hernia repair is well documented [1,2]. place. Face mask oxygen was supplemented at 5 lt/min. The technical difficulty in identifying and selectively Intravenous (i.v) sedation was given using propofol: blocking the nerves concerned makes the subject to be ketamine mixture in the ratio 4:1 infused at 5 ml/hr. -

Robotic Surgery for Male Infertility

Robotic Surgery for Male Infertility Annie Darves-Bornoz, MD, Evan Panken, BS, Robert E. Brannigan, MD, Joshua A. Halpern, MD, MS* KEYWORDS Robotic surgical procedures Infertility Male Vasovasostomy Varicocele KEY POINTS Robotic-assisted approaches to male infertility microsurgery have potential practical benefits including reduction of tremor, 3-dimensional visualization, and decreased need for skilled surgical assistance. Several small, retrospective studies have described robotic-assisted vasectomy reversal with com- parable clinical outcomes to the traditional microsurgical approach. Few studies have described application of the robot to varicocelectomy, testicular sperm extrac- tion, and spermatic cord denervation. The use of robotic-assistance for male infertility procedures is evolving, and adoption has been limited. Rigorous studies are needed to evaluate outcomes and cost-effectiveness. INTRODUCTION with intraperitoneal and pelvic surgery. On the other hand, many of the theoretic and practical ad- Up to 15% of couples have infertility, with approx- 1,2 vantages offered by the robotic approach are imately 50% of cases involving a male factor. A highly transferrable to surgery for male infertility: substantial proportion of men with subfertility have surgically treatable and even reversible etiologies, High quality, 3-dimensional visualization is such as a varicocele or vasal obstruction. The essential for any microsurgical procedure. introduction of the operating microscope revolu- Improved surgeon ergonomics are always desir- tionized the field of male infertility, dramatically able, particularly given the surgeon morbidity improving visualization of small, complex associated with microsurgery.3 anatomic structures. The technical precision Filtering of physiologic tremor can improve pre- afforded has improved operative outcomes across cision during technically demanding micro- the board. -

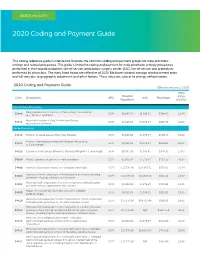

2020 Coding and Payment Guide

MEN’S HEALTH 2020 Coding and Payment Guide This coding reference guide is intended to illustrate the common coding and payment groups for male prosthetic urology and related procedures. This guide is limited to coding and payment for male prosthetic urology procedures performed in the hospital outpatient site-of-service, ambulatory surgery center (ASC) site-of-service and procedures performed by physicians. The rates listed below are reflective of 2020 Medicare national average reimbursement rates and will vary due to geographic adjustment and other factors. These rates are subject to change without notice. 2020 Coding and Payment Guide Effective January 1, 2020 Total Hospital Code Description APC ASC Physicians RVUs Outpatient (Facility) Urinary Sling Procedures Sling operation for correction of male urinary incontinence 53440 5376 $8,067.93 $6.546.11 $784.59 21.74 (e.g., fascia or synthetic) Removal or revision of sling for male incontinence 53442 5375 $4,231.62 $1,976.27 $816.35 22.62 (e.g., fascia or synthetic) Penile Procedures 54110 Excision of penile plaque (Peyronie’s Disease) 5374 $3,018.54 $1,376.97 $650.33 18.02 Excision of penile plaque (Peyronie’s Disease); with graft up 54111 5375 $4,231.62 $1,976.27 $834.03 23.11 to 5 cm in length 54112 Excision of penile plaque (Peyronie’s Disease); with graft > 5 cm in length 5376 $8,067.93 $3,995.65 $976.95 27.07 54360 Plastic operation on penis to correct angulation 5374 $3,018.54 $1,376.97 $751.39 20.82 54400 Insertion of penile prosthesis; non-inflatable (semi-rigid) 5377 $17,573.96 -

REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM by Dr.Ahmed Salman Assistant Professor of Anatomy &Embryology Male Genital System Learning Objectives

The University Of Jordan Faculty Of Medicine Anatomy Department REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM By Dr.Ahmed Salman Assistant Professor of Anatomy &embryology Male genital system Learning Objectives 1. Identify External and Internal male organs 2. Discuses different scrotal layers 3. Know different content of the scrotum 4. Learn anatomy of the penis 5. Identify structure of the prostate 6. Know the course and relation of vas deferens 7. Enumerate blood , nerve supply and lymphatic drainage of External male genitalia Male External Genital Organs 1. Scrotum 2. Testis 3. Epididymis 4. Spermatic cord 5. Penis The scrotum The scrotum is a cutaneous pouch, containing testis, epididymis and lower part of the spermatic cord (of both sides). Layers of scrotum Skin :- The skin of the scrotum is pigmented, rugose and is marked by a longitudinal median raphe. Superficial fascia of the scrotum:- The fatty layer is absent (to assist heat loss) and is replaced by the subcutaneous dartos muscle formed of involuntary muscle fibers. The muscle is supplied by sympathetic nerve fibers reaching it through the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve. The muscle aids heat regulation of testis and scrotum. The deep membranous layer of the scrotum is called Colles' fascia. It is continuous superiorly with Scarpa's fascia of the anterior abdominal wall A comparison between layers of scrotum and that of anterior abdominal wall Layers of the anterior abdominal wall Layers of the scrotum Skin Skin Superficial fascia Superficial fascia Superficial fatty layer Replaced by Dartos -

MORPHOMETRIC STUDY of INGUINAL CANAL on CADAVER Vipin Kumar *1, Jignesh Patel 2, Chakraprabha Sharma 3, Suman Inkhiya 4

International Journal of Anatomy and Research, Int J Anat Res 2018, Vol 6(2.1):5172-75. ISSN 2321-4287 Original Research Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.16965/ijar.2018.147 MORPHOMETRIC STUDY OF INGUINAL CANAL ON CADAVER Vipin Kumar *1, Jignesh Patel 2, Chakraprabha Sharma 3, Suman Inkhiya 4. *1 Associate Professor Department of Anatomy American International Institute of Medical Sciences, Udaipur Rajasthan, India. 2 Assistant Professor Department of Anatomy, American International Institute of Medical Sciences, Udaipur Rajasthan, India. 3 Tutor, Department of Anatomy, American International Institute of Medical Sciences, Udaipur Rajasthan, India. 4 Tutor, Department of Anatomy American International Institute of Medical Sciences, Udaipur Rajasthan, India. ABSTRACT Background: The inguinal canal is an oblique intermuscular passage lying above the medial half of the inguinal ligament. Its size and form vary with age and sex, although it is present in both sexes, it is most well developed in male. The inguinal canal in both sexes has been studied by many workers both in India and in other countries. It is observed that the inguinal hernia and recurrence of hernia after surgery is very common in the kosi region of Bihar. This observational study may help the surgeons during the operation of inguinal hernia. Materials and Methods: Present study conducted at the department of Anatomy, Katihar medical college and hospital Katihar and Lord Buddha Kosi Medical College, Saharsa during the period of 2010 to 2016. The cadaver provided for dissection to the student of first professional MBBS, are selected for the study. Cadavers with injured groin region are not taken for the study.