Temple Festivals and Temple Fairs in Old Beijing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

The Old Beijing Gets Moving the World’S Longest Large Screen 3M Tall 228M Long

Digital Art Fair 百年北京 The Old Beijing Gets Moving The World’s Longest Large Screen 3m Tall 228m Long Painting Commentary love the ew Beijing look at the old Beijing The Old Beijing Gets Moving SHOW BEIJING FOLK ART OLD BEIJING and a guest artist serving at the Traditional Chinese Painting Research Institute. executive council member of Chinese Railway Federation Literature and Art Circles, Beijing genre paintings, Wang was made a member of Chinese Artists Association, an Wang Daguan (1925-1997), Beijing native of Hui ethnic group. A self-taught artist old Exhibition Introduction To go with the theme, the sponsors hold an “Old Beijing Life With the theme of “Watch Old Beijing, Love New Beijing”, “The Old Beijing Gets and People Exhibition”. It is based on the 100-meter-long “Three- Moving” Multimedia and Digital Exhibition is based on A Round Glancing of Old Beijing, a Dimensional Miniature of Old Beijing Streets”, which is created by Beijing long painting scroll by Beijing artist Wang Daguan on the panorama of Old Beijing in 1930s. folk artist “Hutong Chang”. Reflecting daily life of the same period, the The digital representation is given by the original group who made the Riverside Scene in the exhibition showcases 120-odd shops and 130-odd trades, with over 300 Tomb-sweeping Day in the Chinese Pavilion of Shanghai World Expo a great success. The vivid and marvelous clay figures among them. In addition, in the exhibition exhibition is on display on an unprecedentedly huge monolithic screen measuring 228 meters hall also display hundreds of various stuffs that people used during the long and 3 meters tall. -

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access China Studies published for the institute for chinese studies, university of oxford Edited by Micah Muscolino (University of Oxford) volume 39 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chs Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Understanding Chaoben Culture By Ronald Suleski leiden | boston Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover Image: Chaoben Covers. Photo by author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Suleski, Ronald Stanley, author. Title: Daily life for the common people of China, 1850 to 1950 : understanding Chaoben culture / By Ronald Suleski. -

Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties

WHC Nomination Documentation File Name: 1004.pdf UNESCO Region: ASIA AND THE PACIFIC __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties DA TE OF INSCRIPTION: 2nd December 2000 STATE PARTY: CHINA CRITERIA: C (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (vi) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Criterion (i):The harmonious integration of remarkable architectural groups in a natural environment chosen to meet the criteria of geomancy (Fengshui) makes the Ming and Qing Imperial Tombs masterpieces of human creative genius. Criteria (ii), (iii) and (iv):The imperial mausolea are outstanding testimony to a cultural and architectural tradition that for over five hundred years dominated this part of the world; by reason of their integration into the natural environment, they make up a unique ensemble of cultural landscapes. Criterion (vi):The Ming and Qing Tombs are dazzling illustrations of the beliefs, world view, and geomantic theories of Fengshui prevalent in feudal China. They have served as burial edifices for illustrious personages and as the theatre for major events that have marked the history of China. The Committee took note, with appreciation, of the State Party's intention to nominate the Mingshaoling Mausoleum at Nanjing (Jiangsu Province) and the Changping complex in the future as an extention to the Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing dynasties. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS The Ming and Qing imperial tombs are natural sites modified by human influence, carefully chosen according to the principles of geomancy (Fengshui) to house numerous buildings of traditional architectural design and decoration. They illustrate the continuity over five centuries of a world view and concept of power specific to feudal China. -

June 2021 CHINA | JAPAN | VIETNAM | CAMBODIA | LAOS | SRI LANKA

Small Group Tours and Tailor-Made Journeys January 2020 - June 2021 CHINA | JAPAN | VIETNAM | CAMBODIA | LAOS | SRI LANKA Welcome to Links Travel & Tours! As always, our brochure is filled with inspirational small group tours for those who prefer to travel with like-minded people, and suggested itineraries, for those who prefer a tailor-made option. We also have a variety of suggestions for those who love sport, including golf in Vietnam and Japan, hiking and mountain climbing in Japan and cycling in China and Vietnam. Our sister company, Sport Links Travel provides tours to major sporting events across the globe, including cricket, rugby and Formula 1. Please go to page 146 for more details. At Links Travel & Tours we care about our destinations, and this year we continue to commit to responsible travel wherever we can. When possible, we have changed our domestic flights into intercity train journeys, made easier by the development of the rail network across Asia. Our continued partnership with local hotels and businesses contribute to the local economy and we encourage holidaymakers to support local initiatives. We are committed to reducing our eco impact when introducing you to Asia. Finally, please feel free to get in touch with our dedicated team of Personal Travel Advisers who are on hand to listen, understand and help you arrange your holiday of a lifetime! Xiexie Helen Li - (Owner, Links Travel & Tours) WHY LINKS TRAVEL & TOURS page 4 CHINA page 6 JAPAN page 50 INDOCHINA page 96 SRI LANKA page 130 STOPOVERS page 142 USEFUL INFORMATION page 145 SPORT LINKS TRAVEL page 146 3 WHY TRAVEL WITH LINKS TRAVEL & TOURS Remarkable Value Tailor-Made Journeys Our offices in London, Beijing and Tokyo, For the very best tailor-made journey, we will ensure we have direct contact with hotels, have a conversation with you to understand transport providers and guides, assuring you what you want, and then design an itinerary receive the best value for money. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0149581v Author Liu, Yishi Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 By Yishi Liu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Wen-Hsin Yeh Fall 2011 Abstract Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 By Yishi Liu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Examining the urban development and social change of Changchun during the period 1932-1957, this project covers three political regimes in Changchun (the Japanese up to 1945, a 3-year transitional period governed by the Russians and the KMT respectively, and then the Communist after 1948), and explores how political agendas operated and evolved as a local phenomenon in this city. I attempt to reveal connections between the colonial past and socialist “present”. I also aim to reveal both the idiosyncrasies of Japanese colonialism vis-à-vis Western colonialism from the perspective of the built environment, and the similarities and connections of urban construction between the colonial and socialist regime, despite antithetically propagandist banners, to unfold the shared value of anti-capitalist pursuit of exploring new visions of and different paths to the modern. -

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins In

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins in Experimental Photography from China Xavier Ortells-Nicolau Directors de tesi: Dr. Carles Prado-Fonts i Dr. Joaquín Beltrán Antolín Doctorat en Traducció i Estudis Interculturals Departament de Traducció, Interpretació i d’Estudis de l’Àsia Oriental Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 ii 工地不知道从哪天起,我们居住的城市 变成了一片名副其实的大工地 这变形记的场京仿佛一场 反复上演的噩梦,时时光顾失眠着 走到睡乡之前的一刻 就好像门面上悬着一快褪色的招牌 “欢迎光临”,太熟识了 以到于她也真的适应了这种的生活 No sé desde cuándo, la ciudad donde vivimos 比起那些在工地中忙碌的人群 se convirtió en un enorme sitio de obras, digno de ese 她就像一只蜂后,在一间屋子里 nombre, 孵化不知道是什么的后代 este paisaJe metamorfoseado se asemeja a una 哦,写作,生育,繁衍,结果,死去 pesadilla presentada una y otra vez, visitando a menudo el insomnio 但是工地还在运转着,这浩大的工程 de un momento antes de llegar hasta el país del sueño, 简直没有停止的一天,今人绝望 como el descolorido letrero que cuelga en la fachada de 她不得不设想,这能是新一轮 una tienda, 通天塔建造工程:设计师躲在 “honrados por su preferencia”, demasiado familiar, 安全的地下室里,就像卡夫卡的鼹鼠, de modo que para ella también resulta cómodo este modo 或锡安城的心脏,谁在乎呢? de vida, 多少人满怀信心,一致于信心成了目标 en contraste con la multitud aJetreada que se afana en la 工程质量,完成日期倒成了次要的 obra, 我们这个时代,也许只有偶然性突发性 ella parece una abeja reina, en su cuarto propio, incubando quién sabe qué descendencia. 能够结束一切,不会是“哗”的一声。 Ah, escribir, procrear, multipicarse, dar fruto, morir, pero el sitio de obras sigue operando, este vasto proyecto 周瓒 parece casi no tener fecha de entrega, desesperante, ella debe imaginar, esto es un nuevo proyecto, construir una torre de Babel: los ingenieros escondidos en el sótano de seguridad, como el topo de Kafka o el corazón de Sión, a quién le importa cuánta gente se llenó de confianza, de modo que esa confianza se volvió el fin, la calidad y la fecha de entrega, cosas de importancia secundaria. -

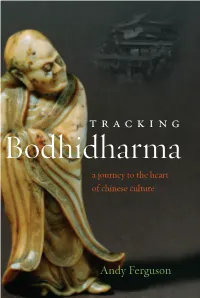

Tracking B Odhidharma

/.0. !.1.22 placing Zen Buddhism within the country’s political landscape, Ferguson presents the Praise for Zen’s Chinese Heritage religion as a counterpoint to other Buddhist sects, a catalyst for some of the most revolu- “ A monumental achievement. This will be central to the reference library B)"34"35%65 , known as the “First Ances- tionary moments in China’s history, and as of Zen students for our generation, and probably for some time after.” tor” of Zen (Chan) brought Zen Buddhism the ancient spiritual core of a country that is —R)9$%: A4:;$! Bodhidharma Tracking from South Asia to China around the year every day becoming more an emblem of the 722 CE, changing the country forever. His modern era. “An indispensable reference. Ferguson has given us an impeccable legendary life lies at the source of China and and very readable translation.”—J)3! D54") L))%4 East Asian’s cultural stream, underpinning the region’s history, legend, and folklore. “Clear and deep, Zen’s Chinese Heritage enriches our understanding Ferguson argues that Bodhidharma’s Zen of Buddhism and Zen.”—J)5! H5<4=5> was more than an important component of China’s cultural “essence,” and that his famous religious movement had immense Excerpt from political importance as well. In Tracking Tracking Bodhidharma Bodhidharma, the author uncovers Bodhi- t r a c k i n g dharma’s ancient trail, recreating it from The local Difang Zhi (historical physical and textual evidence. This nearly records) state that Bodhidharma forgotten path leads Ferguson through established True Victory Temple China’s ancient heart, exposing spiritual here in Tianchang. -

Party Animals in Celebration of Pets, Dog Crusaders, and Conservation Efforts

June 2015 Plus: Hat-making parties with A Walk on the Wild Side Elisabeth Koch, a special Father’s Monkeying around at Day makeover, and more Beijing Wildlife Park Pawsitively Pawdorable Daystar students tell us why they love their pets Party Animals In celebration of pets, dog crusaders, and conservation efforts JUNE 2015 CONTENTS 20 24 34 LIVING DINING 16 “Sports Are Not Only Physical, 32 Dining Out But Also Mental” Blue Elephant bring tastes of southeast Asia to Beijing Coach Jean-Pierre Evers gives advice on raising active kids 34 Food for Thought 17 Coping with Departure Season Irina Glushkova and her girls make Russian breakfast ricotta Helping your children through tough transitions 18 Noticeboard News and announcements around town PLAYING 20 Birthday Bash Fab hat-making workshops with Milliner Elisabeth Koch 36 What’s Fun In 22 Talking Shop Up close and personal with rare animals at Beijing Wildlife Park Rose Fulbright’s luxurious, eco-friendly loungewear collections 40 Playing Outside 24 Indulge Easy getaways for beating the summer heat Kevin Reitz gets his mustache waxed 44 Family Travels The Borghetti-Acciarini family visits the Australian great outdoors HEALTH LEARNING 26 The Natural Path Melissa Rodriguez weighs the benefits of water and sports drinks 46 My Pet Students from Daystar Academy write about their furry companions 27 Doctor’s Orders Dr. Dorothy Dexter’s tips for allergy season 52 When I Grow Up CISB students flock to bird expert Terry Townshend 28 Vegging Out The skinny on switching to a meat-free diet 54 Blank -

2018 Nazareth in China Short-Term Study Abroad Experience

2018 Nazareth in China Short-term Study Abroad Experience Overall Program Itinerary and Rationale for Itinerary: This 2014 Nazareth in China short-term study abroad experience program overview should provide a general sense of how the 2018 trip will look with some changes in destinations and price. It is designed to fully immerse college students in the culture, history, society, and economy of China. For 18 days, students will crisscross the country with Professors Nevan Fisher and Yuanting Zhao, specialists in China’s history and performing arts. Students will be exposed to China’s rich diversity and dynamic vibrancy – traits largely unknown to most Americans. By exploring the country through the prism of “paired opposites,” students will witness this diversity themselves. We will travel from rich coastal areas to poor interior zones, study the clash of traditions with the fast paced race to modernize, witness explosive capitalism under the watchful gaze of the Communist Party, and experience the dizzying shift from extreme urbanization to sleepy rural villages. The 18-day national study tour follows a grand circuit across China’s vast expanse, running counterclockwise from the north to the east. It includes the megacities of Beijing, Shanghai, and Xi’an, as well as the remote mountains of Hunan Province in the central southwest, and the rice fields and karst topography of the far south (the actual mountain range is dependent on estimates of our final trip costs). These locations include both the political and economic capitals of the country, and the historic capital of an empire more than a thousand years into the past; they also include the dramatic natural landscape featured so prominently in traditional Chinese paintings, and now, even in contemporary American cinema. -

Capitalizing on China

Study Abroad The National Aquatics Centre of China, known Capitalizing on China as 'The Water Cube,' here photographed under construction, is sure to be an exciting competition venue for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Christine Tsai scours the districts of China’s capital for Games. The recently completed National Mandarin immersion programs to suit all tastes Theatre of China in Beijing is seen at left. Beijing Beijing, the capital of the People’s Forbidden City, Beijing is full of historical taught Republic of China, is located in the northeast gems. more than part of central China. It is not only the center With the approach of the 2008 Olympic 28,000 peo- of China’s politics, culture and economy, but games, the face of Beijing is changing nearly ple, learning also the site of dynasties in Chinese history. everyday as the city prepares for guests from 15 languages in Also known as “Peking” which literally means, all over the world with renovations and new over 75 cities world- “northern capital,” Beijing is home to nearly 15 construction throughout the city. Visitors and wide. In Beijing, each campus teaches group million people. students are also getting excited as the 2008 classes daily for four hours. These programs The city is divided into various districts, Olympic games in Beijing provide another are designed for total immersion. AmeriSpan each with its own unique characteristics and great reason to learn the Mandarin language. encourages students to stay with a host fami- attractions. The center of the city is surround- ly so that students have the opportunity to ed by ring roads which become progressively understand daily life for locals as well as to larger as one moves further away from the Chaoyang District practice the language during provided meals. -

Gateway Běijīng 北京

© Lonely Planet Publications 79 GATEWAY B Gateway Běijīng Ě IJ Ī 北京 NG In China, all roads and railways lead to Běijīng. There are flights to just about every domestic city of note, as well as air links to most major cities around the world. Unsurprisingly, many people choose to start or end their trip to China in the political and cultural capital, home to some of the country’s most essential sights. It’s here that you’ll find the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace and the Temple of Heaven, while close by is the Great Wall. Even if you’re only in the city for a couple of days, that’s enough time to get a taste of Běijīng. If you do decide to return, Lonely Planet’s Beijing city guide will point you in the right direction. A vast, sprawling city at first sight, Běijīng is actually a fairly easy place to get around. Five ring roads cut through the city, subway lines and overland rail links connect the centre to the far-flung suburbs, and buses and taxis are cheap and plentiful. Běijīng has some of the best restaurants in the country, a huge array of shops to stock up on essentials for your trip and an ever-improving selection of bars and nightlife. Short-term travellers should stay in the area bordered by the third ring road. Sānlǐtún in Cháoyáng District is home to embassies and a wide range of hotels, restaurants, shops and bars. To the west of Sānlǐtún is Dōngchéng District, the heart of old Běijīng with most of the city’s remaining hútòng – ancient alleyways that crisscross the area.