Russell Smith, Stain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lost Executioner: the Story of Comrade Duch and the Khmer Rouge

THE LOST EXECUTIONER: THE STORY OF COMRADE DUCH AND THE KHMER ROUGE Author: Nic Dunlop Number of Pages: 352 pages Published Date: 04 May 2009 Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781408804018 DOWNLOAD: THE LOST EXECUTIONER: THE STORY OF COMRADE DUCH AND THE KHMER ROUGE The Lost Executioner: The Story of Comrade Duch and the Khmer Rouge PDF Book The narrative of this nonfiction account is engrossing. There was no immediate reaction from the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge cadre who rebelled, fled to Vietnam and later helped to drive them from power. It takes a strong stomach to read some of this, but it's worth it. It was Duch. Readers also enjoyed. In Cambodia, between and , some two million people died at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. Upon the death of Comrade Duch, the 1st Khmer Rouge commander convicted of crimes against humanity, we grieve for those murdered under his direction. Nate Thayer the famed US journalist joined him for the final identification of Duch with many of his This is a very simply and well written book on Nic Dunlop's search to find Duch, the man who ran S21 security prison for the leadership of the Khmer Rouge in Phnom Penh through to Also, can there ever be justice in the true sense, when murderers of your loved ones live This is an excellent book-it is about the author's quest to track down the man responsible for running the S prison from where only 7 people survived out of the 20, that entered. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

SPIONS a Lehallgatandók Nem Tudták Tovább Folytatni a Konverzációt, Nem Volt Mit Lehallgatni

Najmányi László megalapítása bejelentésének, és az aktualitását vesztett punkról az elektronikus tánczenére való áttérésnek. A frontember Knut Hamsun Éhségét olvassa, tudtam meg, aztán megszakadt a vonal. Gyakran előfordult, amikor a lehallgatók beleuntak a lehallgatásba. Ha szétkapcsolták a vonalat, SPIONS a lehallgatandók nem tudták tovább folytatni a konverzációt, nem volt mit lehallgatni. A lehall- gatók egymással dumálhattak, család, főnö- kök, csajok, bármi. Szilveszter napján biztosan Ötvenharmadik rész már délután elkezdtek piálni. Ki akar szilvesz- terkor lehallgatni? Senki. Biszku elvtárs talán. Ha éppen nem vadászik. Vagy a tévében Ernyey Béla. Amikor nyomozót játszik. � Jean-François Bizot6 (1944–2007) francia arisz- Végzetes szerelem, Khmer Rouge, Run by R.U.N. tokrata, antropológus, író és újságíró, az Actuel magazin alapító főszerkesztője7 volt az egyet- „Másképpen írok, mint ahogy beszélek. Másképpen beszélek, mint ahogy gon- len nyugati, aki túlélte a Kambodzsát 1975–79 dolkodom. Másképpen gondolkodom, mint ahogy kellene, és így mind a legmé- között terrorizáló vörös khmerek börtönét. lyebb sötétségbe hull.” A SPIONS 1978 nyarán, Robert Filliou (1926–1987) Franz Kafka francia fluxusművész közvetítésével, Párizsban ismerkedett meg vele. Többször meghívott bennünket vacsorára, és a vidéki kastélyában Az 1979-es évem végzetes szerelemmel indult. Meg ugyan nem vakított, de meg- rendezett, napokig tartó bulikra, ahol megismer- bolondított, az biztos. Művészileg pedig – bár addigra már annyira eltávolodtam kedhettünk a francia punk és new wave szcéna a művészettől, amennyire ez lehetséges – feltétlenül inspirált. Tragikus szerelem prominens művészeivel, producerekkel, mene- volt, a műfaj minden mélységével, szépségével, banalitásával és morbiditásával. dzserekkel, koncertszervezőkkel, független Kívülről nézve persze roppant mulatságos, különösen azért, mert én, a gép, a kém, lemezkiadókkal és a vezető rock-újságírókkal. -

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Abstract This Article

The Memory of the Cambodian Genocide: The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Abstract This article examines the representation of the memory of the Cambodian genocide in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh. The museum is housed in the former Tuol Sleng prison, a detention and torture centre through which thousands of people passed before execution at the Choeung Ek killing field. From its opening in 1980, the museum was a stake in the ongoing conflict between the new Vietnamese- backed government and Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge guerrillas. Its focus on encouraging an emotional response from visitors, rather than on pedagogy, was part of the museum’s attempt to engender public sympathy for the regime. Furthermore, in order to absolve former Khmer Rouge members in government of blame, the museum sort to attribute responsibility for the atrocities of the period to a handful of ‘criminals’. The article traces the development of the museum and its exhibitions up to the present, commenting on what this public representation of the past reveals about the memory of the genocide and the changing political situation in Cambodia. The Tuol Sleng prison (also known by its codename S-21) was the largest centre for torture during the rule of the Cambodian Khmer Rouge (KR) between 1975 and 1979. Prisoners were interrogated at Tuol Sleng before being taken to the Choeung Ek killing field located fifteen kilometres southwest of Phnom Penh. Approximately 20,000 people are believed to have been executed and buried at this site.1 In the wake of the Vietnamese invasion in 1979, two photojournalists discovered Tuol Sleng. -

Learning for Cambodian Women: Exploration Through Narrative Identity and Imagination Alvina Marie Sheeley [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2012 Learning for Cambodian Women: Exploration through Narrative Identity and Imagination Alvina Marie Sheeley [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Recommended Citation Sheeley, Alvina Marie, "Learning for Cambodian Women: Exploration through Narrative Identity and Imagination" (2012). Doctoral Dissertations. 42. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/42 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco LEARNING FOR CAMBODIAN WOMEN: EXPLORATION THROUGH NARRATIVE IDENTITY AND IMAGINATION A Dissertation Presented To The Faculty of School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Organization and Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Education By Alvina Sheeley San Francisco, California December 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Dissertation Abstract Learning for Cambodian Women: Exploration through Narrative Identity and Imagination Research Topic This study explains different ways of thinking about education that may improve the quality of life for women in Cambodia. The present inquiry portrays the personal histories, narratives and hopes of selected women to uncover possible ways in which government and non-government agencies may transform the lives of Cambodian women through education programs. Theory and Protocol This research is grounded in critical hermeneutic theory formulated by Paul Ricoeur (1992) and follows an interpretive approach to field research and data analysis (Herda 1999). -

Curriculum Vitae: Ben Kiernan Full Name: Benedict Francis Kiernan

Curriculum Vitae: Ben Kiernan Full Name: Benedict Francis Kiernan Place and East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Date of Birth: 29 January 1953. Address: Department of History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208324, New Haven, CT 06520-8324, USA. Employment 1975-1977 Tutor in History, University of New South Wales History: 1978-1982 Postgraduate student, History, Monash University 1983 Research Fellow, Ethnic Studies, Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs. 1984-1985 Post-doctoral Fellow, History, Monash University. 1986-1987 Lecturer in History, University of Wollongong. 1988-1990 Senior Lecturer, Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong (with tenure, 1989). 1990-97 Associate Professor of History, Yale University. 1994-99 Founding Director, Cambodian Genocide Program, (http://gsp.yale.edu/case-studies/cambodian-genocide-program) 1997-99 Professor of History, Yale University. 1998-2015 Founding Director, Genocide Studies Program, Yale University (http://gsp.yale.edu) 1999- A.Whitney Griswold Professor of History, Yale University. 2000-02 Convenor, Yale East Timor Project. 2003-08 Honorary Professorial Fellow, University of Melbourne. 2005- Professor of International and Area Studies, Yale University. 2010-15 Chair, Council on Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University. Formal Academic B.A. (Hons), 1st Class, History, Monash University, 1975. Qualifications: Thesis: ‘The Samlaut Rebellion and Its Aftermath, 1967-70: The Beginnings of the Modern Cambodian Resistance’ (131 pp.) Ph.D. in History, Monash University, 1983. Dissertation: ‘How Pol Pot Came to Power: A History of Communism in Kampuchea, 1930-1975’ (579 pp.) Positions Held: Member of the Editorial Boards of Critical Asian Studies (formerly Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars), 1983- ; Human Rights Review, 1999- ; TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia, 2012- ; Zeitschrift für Genozidforschung, 2004- ; Journal of Genocide Research, 1999-2008; Genocide Studies and Prevention, 2006-9; Journal of Human Rights, 2001-7. -

The Perpetrator's Mise-En-Scène: Language, Body, and Memory in the Cambodian Genocide

JPR The Perpetrator’s mise-en-scène: Language, Body, and Memory in the Cambodian Genocide Vicente Sánchez-Biosca Abstract: Rithy Panh’s film S-21. The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine (2003) was the result of a three- year shooting period in the Khmer Rouge centre of torture where perpetrators and victims exchanged experiences and re-enacted scenes from the past under the gaze of the filmmaker’s camera. Yet, a crucial testimony was missing in that puzzle: the voice of the prison’s director, Kaing Guek Eav, comrade Duch. When the Extraor- dinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) were finally established in Phnom Penh to judge the master criminals of Democratic Kampuchea, the first to be indicted was this desk criminal. The filmDuch, Master of the Forges of Hell (Panh, 2011) deploys a new confrontation – an agon, in the terminology of tragedy – between a former perpetrator and a former victim, seen through cinema language. The audiovisual document registers Duch’s words and body as he develops his narrative, playing cunningly with contrition and deceit. The construction of this narrative and its deconstruction by Panh can be more fully understood by comparing some film scenes with other footage shot before, during and after the hearings. In sum, this ‘chamber film’ permits us to analyse two voices: that of the perpetrator, including his narrative and body language; and the invisible voice of the survivor that expresses itself through editing, sound effects, and montage. Keywords: Perpetrator, audiovisual testimony, body language, cinema, Khmer Rouge, Cambodia Gémir, pleurer, prier est également lâche. Fais énergiquement ta longue et lourde tâche Dans la voie où le Sort a voulu t’appeler. -

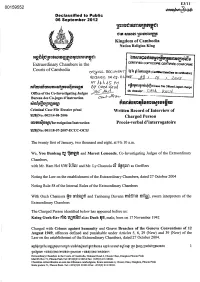

Written Record of Interview of Charged Person As Recorded

00159552 Declassified to Public 06 September 2012 ~ft &1S:l~~ L~~tStm~8i Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King "e~i~;u:@t~Urnfiefi~m~"U~~ t ~ ~~ t ~ I I Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia M'~rew~~6&iLfitS6~e$f6~fi Office of the Co-Investigating Judges Bureau des Co-juges d'instruction ~rul6\leL~~9~ Criminal Case File !Dossier penal Written Record of Interview of "US/No: 002/14-08-2006 Charged Person eJ 6n5e6h1e~$fInvestigation/Instruction Proces-verbal d'interrogatoire .1n!S/No: 001/18-07-2007-ECCC-OCIJ The twenty first of January, two thousand and eight, at 9 h 10 a.m. We, You Bunleng ~ ~1:waol3 and Marcel Lemonde, Co-Investigating Judges of the Extraordinary Chambers, c.J',.",.. ~ ..., with Mr. Ham Hel tnt! nnru and Mr. Ly Chanto1a ru tnum.fI as Greffiers . ~ I Noting the Law on the establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004 Noting Rule 58 of the Internal Rules of the Extraordinary Chambers With Ouch Channora U\1 m~ruui and Tanheang Davann m~Un.j:1 r::nirul, sworn interpreters of the ~ ~ ~ Extraordinary Chambers The Charged Person identified below has appeared before us: Kaing Guek-Eav mol3 ngnii'lf alias Duch qti, male, born oni 7 November 1942 Charged with Crimes against humanity and Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, offences defined and punishable under Articles 5, 6, 29 (New) and 39 (New) of the Law on the establishment of the Extraordiriary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004. H~~~llU1:fMgmqll~Mfflmijm 1:fl1!9mllWl'mn ~tmihrufl Ci! Mirlfl ~mg\m flq{1 ~tirl U'!ll btrtm tUtfUMtrtmrufll1le 1 ~HJ~1rufl +a~~(O)lmn l!JeaiCi!!J ~rM~rufl +a~~(O)l!Jm l!JeaiCi!e"l Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, National Road 4, Choam Chao, Dangkoa Phnom Penh Mail Po Box 71, Phnom Penh Tel:+855(0)23 218914 Fax: +855(0) 23 218941. -

Download Document

Contents Page Investigative Reporting : A Handbook for Cambodian Journalists Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................................................2 Foreword...........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter.1.|.Media.Major.Events.in.Cambodia:.Timeline.................................................................................4 Chapter.2.|.Media.in.Cambodia:.The.current.situation........................................................................................................7 Chapter.3.|.What.has.shaped.Cambodia’s.recent.media?.................................................................................................9 Chapter.4.|.Major.Challenges.Journalists.Face.Doing.Their.Work:...................................................................................12 Chapter.5.|.Investigative.Reporting...............................................................................................................13 Chapter.6.|.Writing.a.Work.Plan....................................................................................................................18 Chapter.7.|.The.Paper.Trail:.A.Question.of.Proof.........................................................................................22 Chapter.8.|.The.Internet:.Blazing.the.Electronic.Trail.of.Documents............................................................28 -

6 Documenting the Crimes of Democratic Kampuchea

Article by John CIORCIARI and CHHANG Youk entitled "Documenting the Crimes of Democratic Kampuchea" in Jaya RAMJI and Beth VAN SCHAAK's book "Bringing the Khmer Rouge to Justice. Prosecuting Mass Violence Before the Cambodian Courts", pp.226-227. 6 Documenting The Crimes Of Democratic Kampuchea John D. Ciorciari with Youk Chhang John D. Ciorciari (A.B., J.D., Harvard; M.Phil., Oxford) is the Wai Seng Senior Research Scholar at the Asian Studies Centre in St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford. Since 1999, he has served as a legal advisor to the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) in Phnom Penh. Youk Chhang has served as the Director of DC-Cam since January 1997 and has managed the fieldwork of its Mass Grave Mapping Project since July 1995. He is also the Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of DC-Cam’s monthly magazine, SEARCHING FOR THE TRUTH, and has edited numerous scholarly publications dealing with the abuses of the Pol Pot regime. The Democratic Kampuchea (DK) regime was decidedly one of the most brutal in modern history. Between April 1975 and January 1979, when the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) held power in Phnom Penh, millions of Cambodians suffered grave human rights abuses. Films, museum exhibitions, scholarly works, and harrowing survivor accounts have illustrated the horrors of the DK period and brought worldwide infamy to the “Pol Pot regime.”1 Historically, it is beyond doubt that elements of the CPK were responsible for myriad criminal offenses. However, the perpetrators of the most serious crimes of that period have never been held accountable for their atrocities in an internationally recognized legal proceeding. -

Suggested Reading List for Cambodia

Suggested Reading List for Cambodia Art & Architecture of Cambodia - Helen Ibbitson Jessup Complemented by numerous photographs of freestanding statuary and illustrations of the temples, Jessup’s history of Cambodia from the perspective of Khmer art is a wonderful story. For those interested in Cambodian religion and culture, including the development and evolution of Khmer temple design and decoration, Jessup lays it out through an overview of Cambodia’s rich legacy of sculpture and temple carving. Angkor and the Khmer Civilization - David D. Coe For those interested in the rise of Khmer civilization from prehistory through Angkor, this is a fascinating read. Unlike other histories that focus largely on the temples, Coe’s focus is on the people, their traditions, and the development of their culture. With maps, illustrations, and colorful descriptions, Coe’s work is a fine introduction to Cambodian history and culture to complement any study of the country before, during, or after a visit. A History of Cambodia - David Chandler Chandler is an expert historian in many Southeast Asian nations, and his history of Cambodia is unparalleled. From the earliest days of the Khmer civilization, through Angkor, and including the years of the Khmer Rouge regime, Chandler lays it all out in an easy to understand yet academically researched analysis. So deep is his understanding of Cambodian history that Chandler testified in the trial of high- ranking Khmer Rouge officials in the years following the war. Angkor: An Introduction to the Temples - Dawn Rooney Rooney’s Angkor: An Introduction to the Temples has grown in girth over the years, but remains one of the most important and easy to understand guidebooks to the temples of Angkor. -

Silence and Voice in Khmer Rouge Mug Shots by Michelle Caswell a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fu

Archiving the Unspeakable: Silence and Voice in Khmer Rouge Mug Shots By Michelle Caswell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 3/20/12 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor, Library and Information Studies Kristin Eschenfelder, Professor, Library and Information Studies Alan Rubel, Assistant Professor, Library and Information Studies Michele Hilmes, Professor, Media and Cultural Studies Anne Gilliland, Professor, Information Studies, UCLA ii ABSTRACT: ARCHIVING THE UNSPEAKABLE: SILENCE AND VOICE IN KHMER ROUGE MUG SHOTS Michelle Caswell Under the Supervision of Professor Christine Pawley at the University of Wisconsin Madison Using theoretical frameworks from archival studies, anthropology, and cultural studies, this dissertation traces the social life of a collection of mug shots taken at the notorious Tuol Sleng Prison in Cambodia and their role in the production of history about the Khmer Rouge regime. It focuses on three key moments in the social life of the mug shots: the moment of their creation; their inclusion in archives; and their use by survivors and victims’ family members in establishing narratives about the Khmer Rouge. The dissertation explores the ways in which silences were encoded in each of these moments, how the meaning of these records changes depending on their context, and how their reuse creates an infinite layering of the archive. The first chapter outlines the key theoretical and methodological frameworks employed, namely Trouillot’s conception of silences and the production of history, the records continuum model, and the social life of objects approach.